Module 3 Application..

advertisement

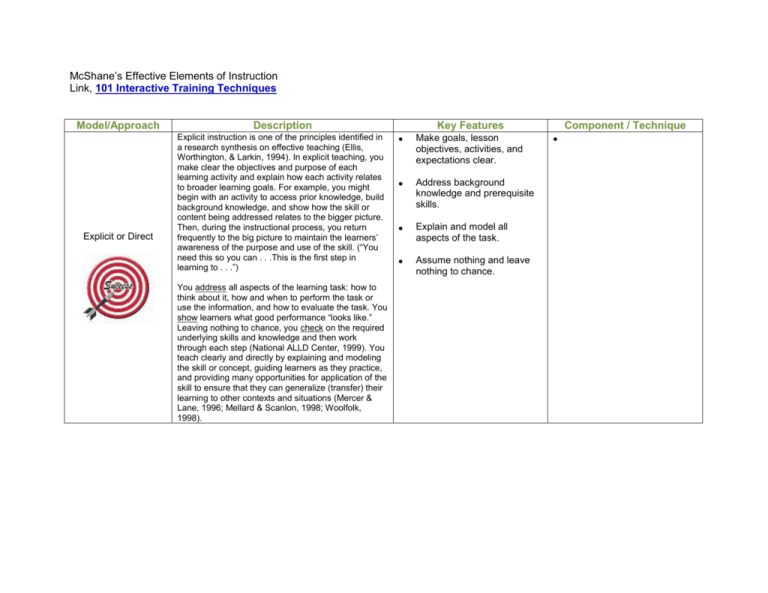

McShane’s Effective Elements of Instruction Link, 101 Interactive Training Techniques Model/Approach Explicit or Direct Description Explicit instruction is one of the principles identified in a research synthesis on effective teaching (Ellis, Worthington, & Larkin, 1994). In explicit teaching, you make clear the objectives and purpose of each learning activity and explain how each activity relates to broader learning goals. For example, you might begin with an activity to access prior knowledge, build background knowledge, and show how the skill or content being addressed relates to the bigger picture. Then, during the instructional process, you return frequently to the big picture to maintain the learners’ awareness of the purpose and use of the skill. (“You need this so you can . . .This is the first step in learning to . . .”) You address all aspects of the learning task: how to think about it, how and when to perform the task or use the information, and how to evaluate the task. You show learners what good performance “looks like.” Leaving nothing to chance, you check on the required underlying skills and knowledge and then work through each step (National ALLD Center, 1999). You teach clearly and directly by explaining and modeling the skill or concept, guiding learners as they practice, and providing many opportunities for application of the skill to ensure that they can generalize (transfer) their learning to other contexts and situations (Mercer & Lane, 1996; Mellard & Scanlon, 1998; Woolfolk, 1998). Key Features Make goals, lesson objectives, activities, and expectations clear. Address background knowledge and prerequisite skills. Explain and model all aspects of the task. Assume nothing and leave nothing to chance. Component / Technique Strategy Strategy instruction is not designed to teach content; instead it teaches learning tools. Strategy instruction aims to teach learners how to learn effectively, by applying principles, rules, or multi-step processes to solve problems or accomplish learning tasks. Examples of strategies include “rules of thumb” to follow, ways to monitor, procedures for breaking the task down, tips for use, and test-taking strategies. In teaching strategies, you model your thought processes, demonstrating when and how to use the strategy and then prompting or cueing learners, as needed, when it is appropriate for them to use a strategy that has been taught (Ellis et al., 1994; Swanson, 1999). Scaffolded instruction is the process of supporting learners in various ways as they learn and gradually withdrawing supports as they become capable of independent performance of a task or skill. Scaffolded Supports include clues, clarifying questions, reminders, encouragement, breaking the problem down into steps, “or anything else that allows the learner to grow in independence” (Woolfolk, 1998, p. 47). According to Swanson, in scaffolded instruction, students are viewed as collaborators and the teacher as “a guide, shaping the instruction and providing support for the learning” (Swanson, 1999, p. 138). This is an interactive process that bases instruction on learners’ prior knowledge, provides needed support, and gradually removes the support as it becomes less necessary (Ellis et al., 1994). Teach learning tools: principles, rules, or multi-step processes to accomplish learning tasks. Model and demonstrate; prompt and cue learners to use strategies. Provide supports for learning as needed: breaking into steps, providing clues, reminders, or encouragement. Withdraw support gradually as it becomes less necessary. Intensive/Active Structured/Segmented The two elements of intensive instruction are active learning and time. Intensive instruction involves active learner engagement and plenty of time on task (Ellis et al.,1994; National ALLD Center, 1999). Students learn more when they are active, that is, not just listening or watching, but applying “focused, sustained effort on the content or task” (Mellard & Scanlon, 1998, p. 293). For example, they might be using a strategy on an unfamiliar problem, practicing through repetition, participating in a discussion, working to solve a familiar problem in a new way, or creating some form of graphic organizer or using digital tools/media. As might be expected, they learn more when they spend more time engaged in such activities. Although it may seem like “overlearning” for learners experienced in the topic, novice learners usually require multiple and frequent practice opportunities. Intensive instruction has also been described as requiring a high degree of learner attention and response and frequent instructional sessions (National ALLD Center). Structured instruction has been defined as the act of “systematically teaching information that has been chunked into manageable pieces” (National ALLD Center, 1999). Complex skills or large bodies of information are broken into parts, which are taught systematically according to a planned sequence. An approach that is described similarly has been termed “segmentation” (Swanson, 1999). You must analyze each task and break it into its component parts, and then after teaching the parts systematically, bring them back together so learners are aware of the process or concept as a whole. Keep learners focused, active, and responding. Provide plenty of “time on task.” Break information and skills into manageable parts. Teach parts systematically and in sequence. Bring the parts together to refocus on the whole.