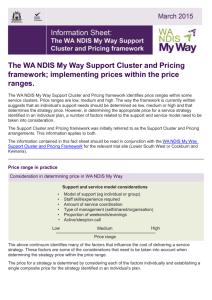

A Practical Design Fund Project

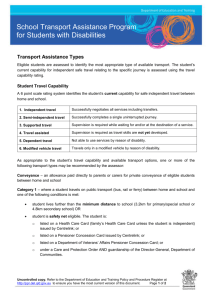

advertisement