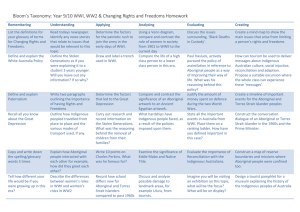

docx of "Social Justice and Native Title Report 2014"

advertisement