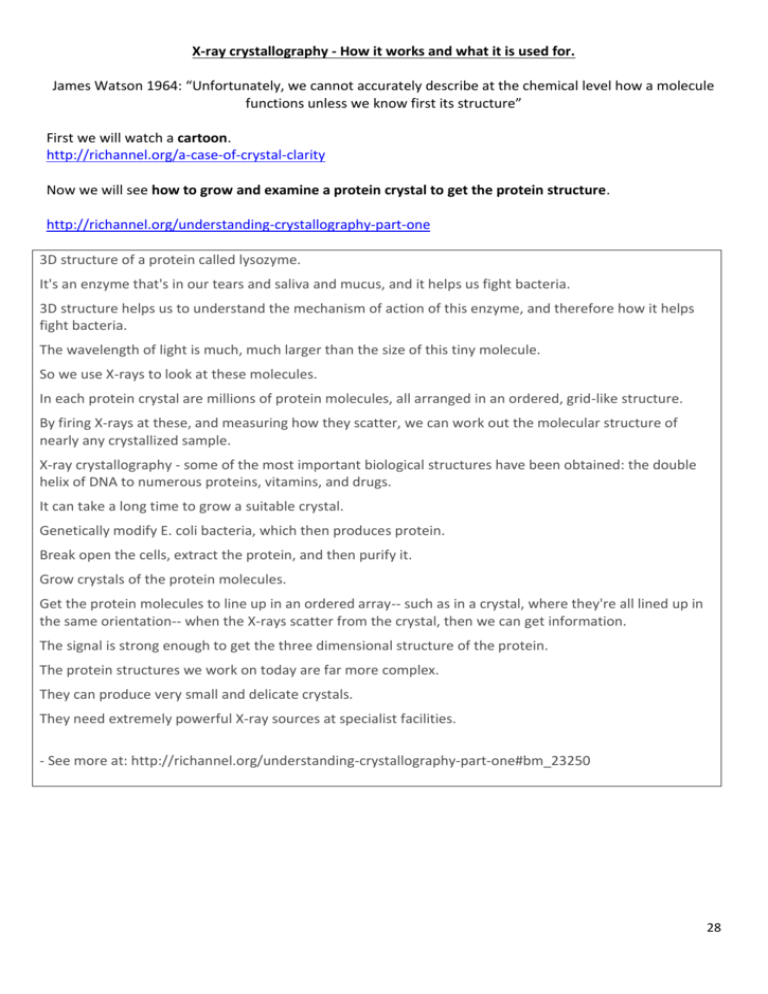

X-ray crystallography - How it works and what it is used for.

James Watson 1964: “Unfortunately, we cannot accurately describe at the chemical level how a molecule

functions unless we know first its structure”

First we will watch a cartoon.

http://richannel.org/a-case-of-crystal-clarity

Now we will see how to grow and examine a protein crystal to get the protein structure.

http://richannel.org/understanding-crystallography-part-one

3D structure of a protein called lysozyme.

It's an enzyme that's in our tears and saliva and mucus, and it helps us fight bacteria.

3D structure helps us to understand the mechanism of action of this enzyme, and therefore how it helps

fight bacteria.

The wavelength of light is much, much larger than the size of this tiny molecule.

So we use X-rays to look at these molecules.

In each protein crystal are millions of protein molecules, all arranged in an ordered, grid-like structure.

By firing X-rays at these, and measuring how they scatter, we can work out the molecular structure of

nearly any crystallized sample.

X-ray crystallography - some of the most important biological structures have been obtained: the double

helix of DNA to numerous proteins, vitamins, and drugs.

It can take a long time to grow a suitable crystal.

Genetically modify E. coli bacteria, which then produces protein.

Break open the cells, extract the protein, and then purify it.

Grow crystals of the protein molecules.

Get the protein molecules to line up in an ordered array-- such as in a crystal, where they're all lined up in

the same orientation-- when the X-rays scatter from the crystal, then we can get information.

The signal is strong enough to get the three dimensional structure of the protein.

The protein structures we work on today are far more complex.

They can produce very small and delicate crystals.

They need extremely powerful X-ray sources at specialist facilities.

- See more at: http://richannel.org/understanding-crystallography-part-one#bm_23250

28

http://richannel.org/understanding-crystallography-part-two#bm_11170

A particle accelerator that can generate beams of light 10 billion times brighter than the sun.

Users are structural biologists doing x-ray crystallography.

In the crystal, the ordering of the molecules means that when we fire x-rays at a crystal, it diffracts or

scatters the beam into hundreds of intense rays.

The resulting diffraction pattern, detected as an array of spots, is dependent on the internal structure of

the crystal.

By measuring the intensities and positions of these spots, we can work back to the structure of the

molecule it is made from.

A pulse of x-rays shoots straight into one of the lead-lined experimental hatches where scientists carry out

their diffraction experiments.

During the experiment, the crystal is cooled by ultra-cold nitrogen gas to help it withstand the radiation.

The diffracted rays are captured on a detector.

X-rays are a form of light that has a wavelength about the size of an atom.

Mathematical understanding of how light scatters allows scientists to work backwards from the diffraction

pattern to a three-dimensional image of the protein in the crystal.

This gives three-dimensional maps, which plot the electron density of the protein molecule.

The resolution of these maps is dependent on the quality of the crystal.

With good quality data, these maps are very detailed. You can see the lumps and bumps of every atom,

every twist and turn of the protein chain.

From these sorts of investigations, we can learn how the biological molecules of your body interact with

one another, or how to design drugs that will bind to them more effectively, or even to design proteins

that nature never got around to inventing.

Korea has a synchrotron at Pohang.

The Pohang Light Source was designed to provide synchrotron radiation with continuous wavelengths

down to 1Å. It's construction was completed in September, 1994. The PLS is a national user facility, owned

and operated by the Pohang Accelerator Laboratory (PAL) and POSTECH on behalf of the Korean

Government.

Now we can study how this information might be used.

29

Structure of Ribosomes

Structure determination by X-ray crystallography

An X-ray structure of a bacterium ribosome. The rRNA-molecules are colored orange, the proteins of the

small subunit are blue and the proteins of the large subunit are green. An antibiotic molecule (red) is

bound to the small subunit. Scientists study these structures in order to design new and more effective

antibiotics.

Different antibiotics can be used in the fight against disease-generating bacteria. Many of these antibiotics

kill bacteria by blocking the functions of their ribosomes. However, bacteria have become resistant to most

of these drugs more often. Therefore we need new ones.

X-ray crystallography structures show how different antibiotics bind to the ribosome. Some of them block

the tunnel through which the growing proteins leave the ribosome, others prevent the formation of the

peptide bond between amino acids. Still others stop the correct translation from DNA/RNA-language into

protein language.

Several companies now use the structures of the ribosome in order to develop new antibiotics

http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/2009/popular-chemistryprize2009.pdf

30

The development of Imatinib

The classic example of targeted development is imatinib mesylate (Gleevec), a

small molecule which inhibits a signaling molecule kinase.

The genetic abnormality causing chronic myelogenous leukemia(CML) has

been known for a long time to be a chromosomal translocation creating an

abnormal fusion protein, kinase BCR-ABL, which signals badly, leading to

uncontrolled proliferation of the leukemia cells.

The Philadelphia chromosome

Discovered in 1960, the diagnostic karyotypic abnormality for chronic myelogenous leukemia is

shown in this picture of the banded chromosomes 9 and 22. Shown is the result of the reciprocal

translocation of 22q to the lower arm of 9 and 9q (c-abl to a specific breakpoint cluster region [bcr] of chromosome 22 indicated by the arrows). ©

2006 Peter C. Nowell Courtesy of Peter C. Nowell, MD, Dept. of Pathology and Clinical Laboratory of the University of Pennsylvania School of

Medicine. All rights reserved.

In 1983, researchers demonstrated that the human c-abl oncogene is located in the region of chromosome 9 that

translocates to become part of the Philadelphia chromosome.

in 1990, scientists infected bone marrow cells with a retrovirus encoding the fusion gene and demonstrated that,

indeed, the presence of an active bcr-abl gene initiates CML or CML-like symptoms

in 1990, researchers identified the function of the bcr-abl fusion gene: production of an abnormal tyrosine

kinase protein that is not properly regulated. Tyrosine kinase is a common signaling molecule that, when activated,

triggers cells to divide. In patients with CML, the mutated tyrosine kinase is active for far too long, causing cells to

proliferate at an abnormally high rate. This proliferation results in the overproduction and accumulation of immature

white blood cells, which is the sign of CML. A milliliter of blood from a healthy person contains about 4,000 to 10,000

white blood cells, the same volume of blood from a person with CML contains 10 to 25 times that amount.

Scientists learned about kinase structure, and found considerable variation among the different kinases with respect

to the structure of their ATP-binding pockets. This meant that a drug that only blocks the bcr-abl ATP binding site

might be possible.

Ciba-Geigy (which later became Novartis), were conducting tyrosine kinase inhibitor research. They had already

synthesized some kinase-blocking inhibitor compounds, using computer models to predict which molecular

structures might fit the ATP-binding site of the fusion protein.

Imatinib precisely inhibits this kinase.

Brian Druker had researched the abnormal enzyme kinase in CML.

He thought that precisely inhibiting this kinase with a drug would

control the disease and have little effect on normal cells.

Druker collaborated with Novartis chemist Nicholas Lydon, who

developed several candidate inhibitors.

From these, imatinib was found to have the most promise in laboratory

experiments.

Druker found that when this small molecule is used to treat patients

with chronic-phase CML, 90% achieve complete haematological

remission.

It is hoped that molecular targeting of similar defects in other cancers

will have the same effect.

31

Imatinib is marketed by Novartis as Gleevec or Glivec. It is a tyrosine-kinase inhibitor used in the treatment of

multiple cancers.

Like all tyrosine-kinase inhibitors, imatinib works by

preventing a tyrosine kinase enzyme, in this case

BCR-Abl, from phosphorylating subsequent proteins

and initiating the signalling cascade necessary for

cancer development, thus preventing the growth of

cancer cells and leading to their death by

apoptosis. Because the BCR-Abl tyrosine kinase

enzyme exists only in cancer cells and not in healthy

cells, imatinib works as a form of targeted therapy—

only cancer cells are killed through the drug's

action. Imatinib was one of the first cancer therapies

to show the potential for such targeted action, and is

often cited as a paradigm (very good example) for

research in cancer therapeutics.

Crystallographic structure of tyrosine-protein kinase ABL (rainbow colored, Nterminus = blue, C-terminus = red) complexed with imatinib (spheres, carbon =

white, oxygen = red, nitrogen = blue).

Here is an animation of how Gleevec works.

http://www.dnalc.org/resources/3d/32-how-gleevec-works.html

Rational drug design

Flow chart for structure based drug design.

By Laozhengzz CC A-SA 3.0 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Flow_chart_for_structure_based_drug_design.jpg

References:

Pray, L. (2008) Gleevec: the breakthrough in cancer treatment. Nature Education 1(1):37

http://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/gleevec-the-breakthrough-in-cancer-treatment-565#

Imatinib http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gleevec

32