F Heifer International View #1 Now

advertisement

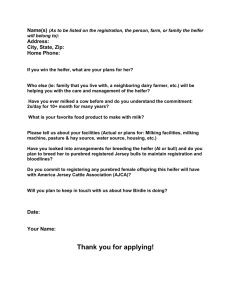

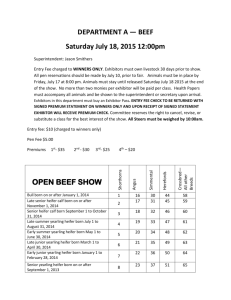

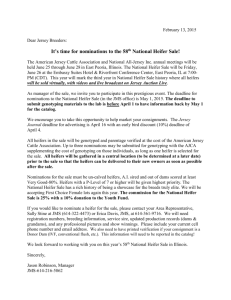

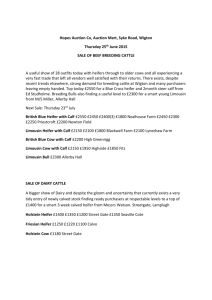

‘A cow, not a cup’ The reach of Heifer International By Roz Cummins December 5, 2007 Editor’s note: We’re grateful to Roz Cummins, who took time to find out more about Heifer International, one of the food-related organizations we’re pleased to support. The clearest explanation of Heifer International lies in the story of its creation: In the 1930s, during the Spanish Civil War, a young man from Indiana named Dan West volunteered as a non-combatant. One of his tasks was to give powdered milk to the war’s many refugees. But West realized that there was no such thing as endless cups of powdered milk. What the refugees truly needed was “a cow, not a cup.” A Nepalese woman with her water buffalo. After returning home, West talked with friends about what he’d seen in Spain, and they decided to send some cows to the refugees. Instead of having to rely on volunteers, the refugees would have direct control over their access to milk. When the cows gave birth, the calves would then be given to other families. This idea of “passing on the gift” is one of the basic founding principles of Heifer International. Heifer International officially became a nonprofit in 1944. As time went on, the organization sent animals to many countries (even countries not on good diplomatic terms with United States), because Heifer believed that the work should transcend politics. So far, Heifer has been involved with bringing 30 kinds of livestock to 50 countries, including nations in Asia, Africa, Europe, and South America. The organization also has several projects in both rural and urban settings around the United States, because hunger and poverty exist here as well. A Peruvian woman with a llama. The structure of Heifer International’s work is simple: Once a community that would benefit from receiving animals is identified, in-country staffers encourage villagers to apply to the program. When the animals arrive, lessons are given in husbandry and animal care. The families who receive the animals are entirely responsible for the animals’ well-being, and when they pass the animals’ offspring on to other families, they’re also responsible for training the families in how to care for their new animals. A single village might receive many animals, such as 18 female goats and 2 male goats, ensuring that there will be offspring to pass on to other families. In places where refrigeration is available, however (such as the U.S.), artificial insemination might be used as well. Usually the animals that Heifer International introduces into a village are used for milk or as draft animals; their dung is used as fertilizer as well. But some are raised solely to be eaten, such as rabbits and guinea pigs. Heifer International also helps farmers learn how to keep bees, which not only produce honey but also help pollinate the farmers’ crops, producing a much higher yield. Because Heifer International does its work in different countries, the nonprofit has to consider which animals will thrive in the conditions specific to each place and the resources and needs of each community. Stewardship of the earth is another important aspect of Heifer’s work. The organization strives to do more than simply avoid causing damage: it aims to be proactive in its actions and choices, such as breeding drought-tolerant animals and crops for use in areas with little rainfall. (This is a problem that will only grow more pervasive with the climate changes that accompany global warming.) Heifer International’s mission statement reads, “To work with communities to end hunger and poverty and care for the earth.” Christine Volkmer, a spokeswoman for Heifer, has traveled to visit Heifer projects in Guatemala and Ecuador. In one village she visited, she says, the impact of having cows introduced into the community was so profound that everyone there referred to events as taking place either “before the cow” or “after the cow.” An unmarried woman was the owner of the cow, and this gave her new standing and respect within the community. Much of Heifer International’s work is about dignity as well as the alleviation of poverty and material needs. Volkmer says that some people who do not support meat-eating would rather that Heifer only provide help with animals that can be milked, hens that lay eggs, or crops. Although originally a religious organization, Heifer does not have a religious affiliation and does not proselytize. Heifer International also operates three learning centers in the U.S.: in Massachusetts, California, and Arkansas. In addition to introducing visitors to sustainable farming and natural-resource management, these learning centers also maintain gardens where they can demonstrate organic farming techniques and teach alternative marketing methods to small-scale farmers. Not just cows, but information. Heifer hopes to pass along not just human aid but global aid. Roz Cummins writes about food in Boston. She is a regular contributor to Grist and a frequent contributor to Culinate. Hi-Lite in YELLOW the statements that most closely summarize the author’s thesis or conclusion. In your own words summarize that thesis or conclusion: Hi-Lite in ORANGE the evidence which supports the author’s thesis or conclusion. In your own words summarize the evidence that supports the author’s thesis or conclusion: Hi-Lite in GREEN the statements which are a fact. (Do not highlight over orange or yellow) In your own words, summarize the key words or phrases that usually indicate a statement is a fact: Hi-Lite in PINK the statements which are an opinion. (Do not highlight over orange or yellow) In your own words, summarize the key words or phrases that usually indicate a statement is an opinion: Sort the 5 most persuasive facts and opinions (may also use highlighted orange items) into the following table showing what the author thinks about Heifer International: Support for Heifer International Against Heifer International Fact Fact Fact Fact Fact Opinion Opinion Opinion Opinion Opinion What does the author do to let readers know what he thinks about Heifer International?