Geographic Luck

advertisement

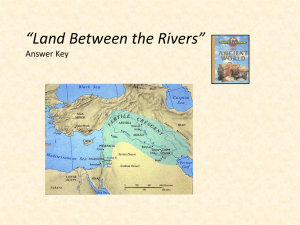

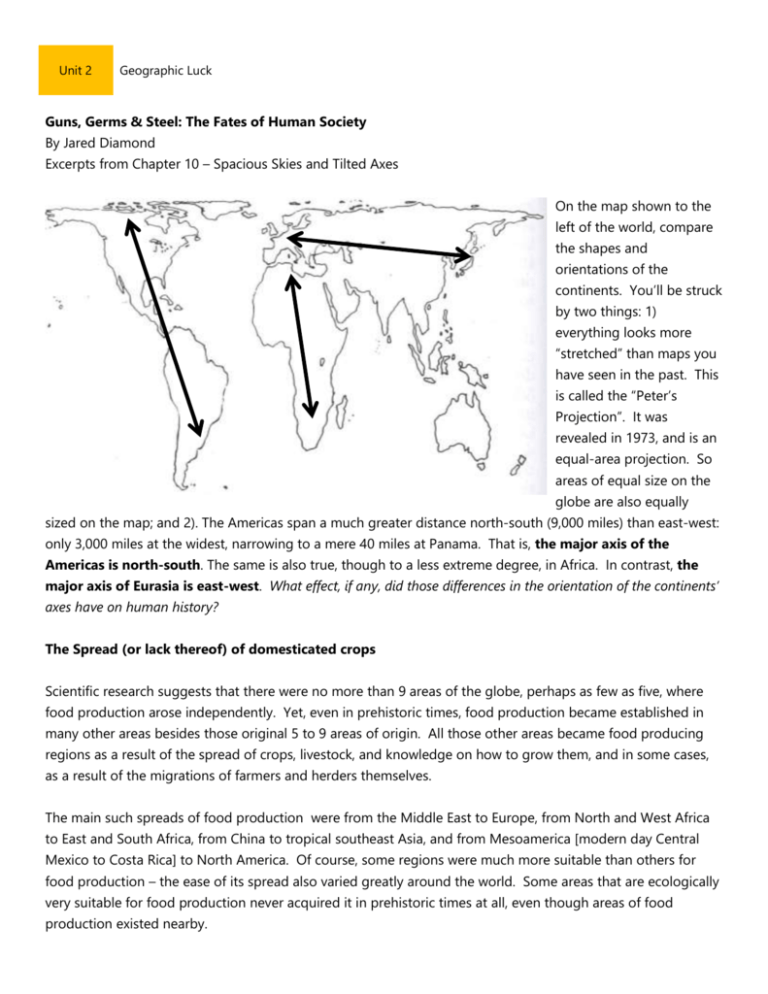

Unit 2 Geographic Luck Guns, Germs & Steel: The Fates of Human Society By Jared Diamond Excerpts from Chapter 10 – Spacious Skies and Tilted Axes On the map shown to the left of the world, compare the shapes and orientations of the continents. You’ll be struck by two things: 1) everything looks more “stretched” than maps you have seen in the past. This is called the “Peter’s Projection”. It was revealed in 1973, and is an equal-area projection. So areas of equal size on the globe are also equally sized on the map; and 2). The Americas span a much greater distance north-south (9,000 miles) than east-west: only 3,000 miles at the widest, narrowing to a mere 40 miles at Panama. That is, the major axis of the Americas is north-south. The same is also true, though to a less extreme degree, in Africa. In contrast, the major axis of Eurasia is east-west. What effect, if any, did those differences in the orientation of the continents’ axes have on human history? The Spread (or lack thereof) of domesticated crops Scientific research suggests that there were no more than 9 areas of the globe, perhaps as few as five, where food production arose independently. Yet, even in prehistoric times, food production became established in many other areas besides those original 5 to 9 areas of origin. All those other areas became food producing regions as a result of the spread of crops, livestock, and knowledge on how to grow them, and in some cases, as a result of the migrations of farmers and herders themselves. The main such spreads of food production were from the Middle East to Europe, from North and West Africa to East and South Africa, from China to tropical southeast Asia, and from Mesoamerica [modern day Central Mexico to Costa Rica] to North America. Of course, some regions were much more suitable than others for food production – the ease of its spread also varied greatly around the world. Some areas that are ecologically very suitable for food production never acquired it in prehistoric times at all, even though areas of food production existed nearby. Unit 2 Geographic Luck For instance, both farming and herding failed to reach Native North American California from the US Southwest. The same can be said for Australia, which had both farming and herding practically next door in New Guinea and Indonesia. The opposite is also true. Some farming and herding traveled very, very fast. For instance food and herding traveled rapidly from the Middle East both west to Europe and Egypt and east to the Indus Valley (as fast as 3.2 miles/year). At the opposite extreme was the slow spread along the north-south axes. Corn and beans spread from Mexico northward to the US Southwest at less than 0.3 miles/year. There were also great differences in the completeness of with which groups of crops and livestock spread, again implying stronger or weaker barriers to their spreading. For instance, while most of the Middle East’s crops and livestock did spread west to Europe and east to the Indus Valley and modern day India, neither of the domestic mammals of the Andes in South America (the llama/alpaca and the guinea pig) ever reached Mesoamerica in ancient times. This failure of spreading cries out for explanation. There were very Llamas – present in South America but never made it to Mesoamerica dense farming populations and very complex cities in Mesoamerica, so there can be no doubt that domestic animals (if they had been available) would have been valuable for food, transport, and wool. Except for dogs, Mesoamerica was completely without mammals to fill those needs. However, some crops made it, such as sweet potatoes and peanuts. What selective barrier let some crops through but didn’t allow llamas and guinea pigs? SINGLE VS MULTIPLE DOMESTICATIONS Most WILD plant species from which our crops were derived were very different genetically from area to area. This is because each area would have established (naturally) different mutations necessary for survival. When humans brought about the changes required to transform WILD plants into DOMESTICATED crops, different wild mutations were selectively bred, and then those same mutated crops spread to other communities. So, what that means is that scientists today can look at the genetics of crops today and see if they were developed in just one area and spread or else developed independently in several areas. Unit 2 Geographic Luck If one looks at the genetic analysis for major ancient crops of the Americas, many of them prove to include two or more of alternative wild variants. This suggests that the crops were domesticated independently in at least two different areas. Botanists conclude that lima beans and chili peppers were all domesticated on at least two separate occasions, once in Mesoamerica and once in South America. Likewise, squash was also domesticated independently at least twice, once in Mesoamerica and once in the eastern United States. In contrast, most crops of the ancient Middle East have just one alternative wild variant mutation, suggesting that all modern varieties of that crop stem from only a single domestication. But what does all that mean? What does it imply if the same crop has been repeatedly and independently domesticated in several different regions, and not just once in a single area? Well, we know (historically and from common sense) that if a productive domesticated crop is already available, farmers will surely proceed to grow it rather than start all over again by gathering the crop’s not yet so useful wild relative and domesticating it. Evidence for just a single domestication of a plant suggest that once a plant was domesticated, it The “Three Sisters” of Mesoamerica: Squash, Maize (Corn) and Beans spread quickly to other areas throughout the plant’s range, making the need for other independent domestications of the same plant pointless. However, when we find evidence that the same wild plant was domesticated in several different areas, we infer [conclude] that the crop spread too slowly to stop its domestication elsewhere. The evidence for single domestications in the Middle East but frequent multiple domestications in the America might provide more subtle evidence that crops spread more easily out of the Middle East than in the Americas. We thus have many different factors all converging on the same conclusion: that food production spread more readily out of the Middle East than in the Americas, and possibly also than in sub-Saharan Africa. These factors include some food’s complete failure to reach some ecologically suitable areas; the differences in the rate and selectivity of spread of food; and the differences in whether the crops were single or multiple domestications and the role that would play in the speed and success of certain foods. So…what was it about the Americas and Africa that made the spread of food production more difficult there than in Eurasia? THE EURASIAN EAST-WEST AXIS Soon after food production arose in the Middle East (the Fertile Crescent), somewhat before 8000 BCE, it spread to other parts of western Europe and North Africa. These plants were not independently domesticated. The crops of Europe and India and North Africa were mostly obtained from the Fertile Crescent. For most of Unit 2 Geographic Luck the Fertile Crescent’s founding crops, all cultivated varieties in the world today share only a single mutation. The rapid spread of domesticated crops from the Middle East actually stopped any other possible attempts to domesticate the same wild ancestor plants. Once the crop had become available, there was no further need to gather it from the wild and start domesticating it again. Why was the spread of crops from the Middle East so rapid? Communities distributed east and west of each other at the same latitude share exactly the same day length and seasonal variations. To a lesser degree, they also tend to share the same diseases, temperature and rainfall and types of vegetation. For example, Portugal, northern Iran and Japan are all located at about the same latitude despite the fact that they are 4,000 miles east or west of each other. They are more similar to each other in climate than each is to a location lying even a meager 1,000 miles south. The germination, growth and disease resistance of plants are adapted to precise features of climate. Seasonal changes of day length, temperature, and rainfall send signals that stimulate seeds to germinate, seedlings to grow, and mature plants to develop flowers, seeds and fruit. Those signals are very different with latitude. For example, the growing season – that is, the months with temperatures and day lengths suitable for plant growth – is shortest at high latitudes and longest towards the equator. Imagine a Canadian farmer foolish enough to plant a race of corn adapted to growing farther south, in Mexico. The unfortunate corn plant, following the signals and code, would prepare to thrust up out of the ground in March, only to find itself buried in 10 feet of snow. Even if the plant could be genetically programed to shoot up at a time better suitable for Canada, like late June, the corn plant would still be in trouble for other reasons. Its genes would be telling it to grow slowly over 5 months. That is a perfectly safe strategy in Mexico’s mild climate, but in Canada it would only lead to death by autumn frost before it had produced any mature corn cobs. The plant would also lack genes for resistance to diseases of northern climates. All those features make low-latitude plants poorly adapted to highlatitude conditions, and vice versa. Animals too are adapted to latitude-related features of climate. Look at humans. Some of us can’t stand cold northern winters with their short Unit 2 Geographic Luck days and germs, while others can’t stand hot tropical climates with their own diseases. In recent centuries overseas colonists from cool northern Europe have preferred to migrate to the similarly cool climates of North America, Australia and South Africa. Northern Europeans who were sent out to hot tropical lowland areas used to die in mass of diseases such as malaria, to which tropical people had evolved some genetic resistance. Therefore, Eurasia’s west-east axis allowed Fertile Crescent crops quickly to launch agriculture over the temperate latitudes from Ireland to the Indus Valley, and to enrich the agriculture that arose independently in eastern Asia. While Eurasia provides the world’s widest band of land at the same latitude, and the most dramatic example of the rapid spread of domestication, there are other examples as well. Almost as fast was the eastward spread of subtropical crops and animals from South China, the Philippines and Indonesia (bananas, taro, yams, chickens, pigs and dogs) some 5,000 miles into the tropical Pacific to reach the islands of Polynesia. THE NORTH-SOUTH AXIS OF AFRICA Contrast the ease of east-west diffusion in Eurasia with the difficulties of diffusion along Africa’s north-south axis. Most of the Fertile Crescent crops reached Egypt very quickly and then spread as far south as the cool highlands of Ethiopia, beyond which they didn’t spread. South Africa’s Mediterranean climate would have been idea for the crops, but the 2,000 miles of tropics between Ethiopia and South Africa posed an impossible barrier. Instead, African agriculture south of the Sahara Desert was launched by the domestication of wild Sorghum in the field and cooked on the plate plants like sorghum and African yams that were indigenous to West Africa, and adapted to the warm temperatures, summer rains and constant day lengths of those low latitudes. Similarly, the spread south of Fertile Crescent domestic animals through Africa was stopped or slowed by climate and disease. The horse never became established farther south than West Africa’s kingdoms north of the equator. The advance of cattle, sheep and goats halted for 2,000 years at the northern edge of the Serengeti Plains. Domesticated sheep, cattle and goats finally reached South Africa, but it was 8000 years after Unit 2 Geographic Luck livestock was domesticated in the Fertile Crescent. The domesticated animals never made it through the tropical climate of the middle of Africa, and were also halted by the diseases carried by certain insects, like the Tsetse fly. THE NORTH-SOUTH AXIS OF THE AMERICAS The distance between Mesoamerica and South America is only 1,200 miles, approximately the same as the distance in Eurasia separating the Balkans from the Middle East. The Balkans provided ideal growing conditions for most Middle Eastern crops and livestock, and they spread rapidly. The highlands of Mexico and the Andes in Southern America would similarly had been suitable for many of each other’s crops and domestic animals. A few crops, notably Mexican corn, did indeed spread along the north-south axis. But other crops and domestic animals failed to spread between Mesoamerica and South America. The cool highlands would have been ideal conditions for raising llamas, guinea pigs, and potatoes, all domesticated in the cool high lands of the South American Andes. Yet the northward spread of those crops and animals was stopped completely by the hot lowlands of Central America. 5,000 years after llamas had been domesticated in the Andes, the Maya, Aztecs and all other native societies of Mexico remained without pack animals and without any edible domestic animals except for dogs. On the other hand, domestic turkeys of Mexico and domestic sunflowers of the eastern United States might have thrived in the Andes, but their southward spread was stopped by the tropical climates in-between. Only 700 miles of north-south distance prevented Mexican corn, squash and beans from reaching the US Southwest for several thousand years. For thousands of years after corn was domesticated in Mexico, it failed to spread northward into eastern North America, because of the cooler climates and shorter growing season. It wasn’t until 900 CE, after hardy varieties of corn adapted to northern climates had been developed, could corn-based agriculture contribute to the most complex Native American society of North America, the Mississippian culture – a brief flowering ended by European introduced germs arriving after Columbus. Remember that most Fertile Crescent crops prove, upon genetic study, to come from only a single domestication process. In contrast, many apparently widespread native American crops prove to consist of genetically distinct varieties of the same species, independently domesticated in Mesoamerica, South America and the eastern United States. Those legacies of multiple independent domestications provide further testimony to the slow movement of crops along the Americas’ north-south axis. Unit 2 Geographic Luck FINAL ISSUES THAT NEED TO BE ADDRESSED I have been dwelling on latitude because it is a major factor of climate, growing conditions, and ease of the spread of food production. However, latitude is not the only such factor. It isn’t always true that places close together at the same latitude have the same climate. Land and ecological barriers and also logically important obstacles to diffusion. For instance, crop diffusion between the US Southeast and Southwest was very slow even though these two regions are on the same latitude. That’s because much of the inbetween area of Texas and the southern plains was dry and unsuitable for agriculture. Another example within Eurasia involved the eastern limit of Fertile Crescent crops. As the The Central Asian desert called Karakum – it makes of 70% of the land now called Turkmenistan. crops spread east, there was a shift from predominantly winter rainfall to predominantly summer rainfall that contributed to a much more delayed extension of agriculture, involving different crops and farming techniques. Even farther east, temperate areas of China were isolated from western Eurasian areas with similar climates by the Himalayas and the Central Asian desert. The initial development of food production in China was therefore independent of that at the same latitude in the Fertile Crescent, and gave rise to entirely different crops. The differences in axis orientation affected the spread not only of food production but also of other technologies and inventions. For example, around 3,000 BCE the invention of the wheel in or near the Middle East spread rapidly west and east across much of Eurasia within a few centuries, whereas the wheels invented independently in prehistoric Mexico never spread south the Andes. The principle of alphabetic writing, developed in the western part of the Fertile Crescent by 1500 BCE, spread west to what is now Italy and east to the India within about a thousand years, but the Mesoamerican writing systems that were successful in Mesoamerica for 2000 years never reached the Andes. Unit 2 Geographic Luck Wheels and writing weren’t linked to latitude and day length the way crops are. Instead, the links are indirect. The earliest wheels were parts of ox-drawn carts used to transport agricultural produce. Early writing was restricted to elites supported by food-producing peasants, and it was for complex food-producing societies (such as inventories of goods, record keeping and royal propaganda). In general, societies that engaged in intense exchanges of crops, livestock and technologies related to food production were more likely to become involved in other exchanges as well. America’s patriotic song “America the Beautiful” mentions spacious skies, amber waves of grain, from sea to shining sea. Actually, that song reverses geographic realities. As in Africa, in the Americas the spread of native crops and domestic animals was slowed by skies and environmental barriers. No waves of native grain ever stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific. However, amber waves of wheat and barley did come to stretch from the Atlantic to the Pacific across Eurasia. To bring us all these differences isn’t to claim that widely distributed crops are admirable, or that they testify to the superiority of early Eurasian farmers. They reflect, instead, the orientation of Eurasia’s axis compared with that of the Americas or Africa. Around those axes turned the fortunes of history. Excerpts from: Guns, Germs & Steel Pages 176-191 Jared Diamond, 1999