Best-fit Decisions [, 25 KB]

advertisement

![Best-fit Decisions [, 25 KB]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006613263_1-62a61f810693250e9828b38f77c693b2-768x994.png)

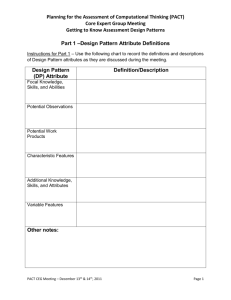

Progress and consistency tool (PACT) Symposium September 29, 2015 Notes for ‘Making a best-fit decision with the PaCT’ Charles Darr, Manager Assessment Design and Reporting, New Zealand Council for Educational Research (NZCER) Introduction Teacher judgments are central to the Progress and Consistency Tool (PaCT). Research tells us that human decision making can be sublime and sometimes it can be ridiculous. So how can we avoid (or at least limit) the ridiculous, and use the PaCT to create dependable information about our students? How we think Psychologists often describe two types or modes of thinking: System 1 and System 2. System 1 is associative, quick, effortless, automatic and always vigilant. For example, when we ‘read’ a face we know almost instantly and effortlessly something about the intentions and character of the person. System 1 is always on, providing impressions, memories, and associations – often more than we need – because of this System 1 is sometimes called a ‘mental shotgun’. System 2 is effortful, rational, analytic and slow, for example, when we purposefully solve a multiplication problem. System 2 draws on, and competes for, a limited amount of mental energy. It is lazy: System 2 will often accept what System 1 presents without much interrogation. System 1 and 2 are useful ways of thinking about how we think – they are not necessarily associated with parts of the brain. Making a judgment When people make judgments and decisions they often use heuristics (mental short cuts) that rely on System 1. This can be very effective but sometimes, using a heuristic, can lead to what is called ‘cognitive bias’. Examples 1. The 3D heuristic: When we judge the features of a 2-dimensional image by automatically creating a 3-dimensional representation in our mind. 2. The availability heuristic: When we base decisions about how likely or frequent an event is by how easily it comes to mind. For example: Do more words have a ‘k’ in the first position (kind, king, kept), or in the third position (lake, acknowledge)? In experiments most people believe the former. There are in fact, three times as many words with ‘k’ in the second position. They are just much harder to think of. The availability heuristic can be manipulated by how recently and how frequently something has been brought to mind – we can be primed without knowing it. 3. The representative heuristic: When we base a judgment on how much something resembles a typical case or a category we know something about. This can lead us to succumb to stereotypes. For example: When science teachers in England scored a sample of work which sometimes had a boys’ names on it and sometimes a girls’ name. Although the scores should have been the same, on average, boys came out with higher scores. 4. The anchoring heuristic: When we make a decision by starting with a reference or starting point and adjusting up and down. We often rely too much on the first piece of information we learn. For example, volunteers in an experiment spun a wheel rigged to stop at either 10 or 65. The volunteers were then asked how many African countries were in the U.N. Those who spun 65 gave higher estimates, while those who spun 10 gave lower estimates. For example, teachers in France were given 12 essays to assess. Each essay came with a fictional list of the last 5 essay marks the student had received. When the average of the 5 marks was high the essay tended to be scored higher by the teachers than when the average was low. According to Kahneman (2012) Constantly questioning our own thinking would be impossibly tedious, and System 2 is much too slow and inefficient to serve as a substitute for System 1 in making routine decisions. The best we can do is a compromise: learn to recognise situations in which mistakes are likely and try harder to avoid significant mistakes when the stakes are high. Making best-fit decisions with the PaCT Research shows that experts make better overall decisions when they use a system to combine relevant information from a number of cues. Experts are often great at recognising important cues, but less reliable when it comes to putting the information together to make a judgment. The PaCT is ultimately a decision framework that asks us to attend to important cues or aspects of what it means to make progress in three key learning areas. Keys to making a best-fit judgment 1. Understand the idea of best-fit “For this aspect, which is the highest set of illustrations that describes what they can do by themselves, most of the time?” 2. Know the PaCT frameworks. Know the aspects Each aspect is about something different, yet related. Focus on what the aspect is about. Know the sets of illustrations Each aspect describes a progression. Each set of illustrations describe a position along that progression that is qualitatively different from the set below and the set above. Each set of illustrations is supported by a description of the big idea behind the set and each illustration is annotated to highlight what is central to the illustration. Each illustration represents a class of problems – it’s not whether the student can solve that particular problem or challenge, or read that particular text. We are deciding whether students reliably (by themselves and most of time) use the kinds of knowledge and skill described to meet the demands of these types of tasks. 3. Watch out for the halo effect An early impression can dictate how we make subsequent judgments. Possibly it’s best to judge different students on each aspect separately, than to judge a single student across the aspects. 4. Justify your decisions Ask: What evidence am I using? How do I know that? 5. Moderate your PaCT judgments with others Work with others to moderate your PaCT decisions – within and across schools. 6. Be mindful about what you are observing and the evidence you collect during the year Use the PaCT frameworks to help guide what you attend to in the classroom. Build up observations and evidence that will be useful. Concluding thoughts Take some inspiration from Virginia Apgar who believed that developing a systematic way to make decisions about new-borns would lead doctors to become more observant and make decisions when it really mattered. Sixty years later the APGAR system has saved countless lives and is still used routinely. Used well, the PaCT can help us attend to what is important and provide information that supports us to be better teachers. References For more information about how we think about and make decisions see: Kahneman, Daniel (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. The ‘about education’ website for interesting articles on different heuristics and cognitive biases (http://www.about.com/education/) For interesting examples of using the 3-dimensional heuristic see: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/03/12/split-depth-gifanimations_n_6851254.html. For information about the gender bias in science study see: Spear, M. G. (1984). Sex bias in science teachers’ ratings of work and pupil characteristics. European Journal of Science Education, 6(4), 369–377. http://doi.org/10.1080/0140528840060407 For information about the French essay marking study see: Caverni, Jean-Paul; Péris, Jean-Luc (1990), "The Anchoring-Adjustment Heuristic in an 'Information-Rich, Real World Setting': Knowledge Assessment by Experts", in Caverni, Jean-Paul; Fabré, Jean-Marc; González, Michel, Cognitive biases, (pp. 35–45). Elsevier. For information about errors in PAT marking see: Chapman, J., St. George, Ibell, R. (1985). Error rate differences in teacher marking of the Progressive Achievement Tests: sex, ability, SES and ethnicity effects. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 20 (2), 165-169. For an interesting read about Virginia Apgar and the use of checklists more generally see: Gawande, A. (2006, October 9). The score. The New Yorker. Retrieved from http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2006/10/09/the-score Gawande, A. (2009). The checklist manifesto: How to get things right. Picador, New York.