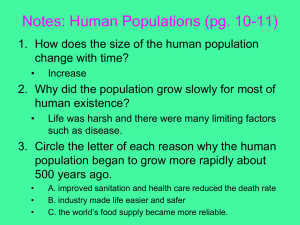

Components of Demographic Dynamics

advertisement