chap3rv6 - the United Nations

advertisement

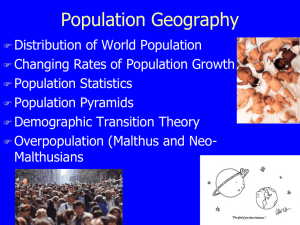

III. POPULATION GROWTH, STRUCTURE AND DISTRIBUTION A. TRENDS AND POLICIES REGARDING and repair the environment, and lay the foundation for future sustainable development. POPULATION GROWTH The Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development (United Nations, 1995, chap. I, resolution 1, annex) lays out a comprehensive approach to issues of population and development, identifying a range of social as well as demographic goals to be achieved over a 20-year period. The Programme of Action contains no specific goals for population growth, but it does reflect the view that early stabilization of the world population would make an important contribution to the achievement of sustainable development. In the more developed regions, the large majority of Governments express satisfaction with their rates of population growth. However, there are signs of increasing concern about low rates of population growth, as fertility has continued to decline to extremely low levels. In 1998, 41 per cent of the countries of the world, and 54 per cent of developing countries, considered their rate of population growth to be too high. That proportion of countries of the world had increased steadily, from 28 per cent in 1974 to 44 per cent in 1993 (table III.1) before dropping to 41 per cent in 1998. This small decrease corresponds to the changing demographic situation in many countries where rates of population growth have declined. Over the decade, from 1985-1990 to 1995-2000, the average rate of population growth globally has declined from 1.7 to 1.3 per cent per year, and in the less developed regions from 2.0 to 1.6 per cent per year. In the less developed regions, the level of fertility, as measured by the total fertility rate, has dropped over the same period from 3.8 births per woman to 3.0. Recognizing that the ultimate goal is the improvement of the quality of life of present and future generations, the objective with respect to population growth is to facilitate the demographic transition as soon as possible in countries where there is an imbalance between demographic rates and social, economic and environmental goals, while fully respecting human rights. This process will contribute to the stabilization of the world population and, together with changes in unsustainable patterns of production and consumption, to sustainable development and economic growth. Continued high rates of population growth remain an issue of policy concern for many Governments, especially in the less developed regions. Governments’ concerns include the difficulties they face in providing education, health and other basic social services to their growing populations. Rapid population growth at the national level is also seen as exacerbating problems associated with population distribution, especially the rapid growth of cities. Growth of rural as well as urban populations has in many places put stress on the local environment. The number of people living in poverty is still on the increase and, despite favourable trends in food production in developing regions as a whole, in some countries, particularly in Africa, population growth has been outpacing increases in food production during the 1980s and 1990s, resulting in a per capita decrease in the amount of food available for human consumption. The Programme of Action reflects a consensus that slower population growth can buy more time for societies to attack poverty, protect The International Conference on Population and Development in 1994 gave new impetus to population and development activities. In the preparation for the Conference and thereafter, new national population policies and programmes were adopted in many countries, including Viet Nam (1993); Bangladesh, Malaysia, and Turkey (1994); the Lao Peoples Democratic Republic (1995); the Republic of Korea (1996); and El Salvador, Nicaragua and Sri Lanka (1997). Some Governments have identified quantitative goals in their development plans to reduce the population growth rate. In general, however, national programmes are shifting their emphasis from quantitative objectives to qualitative issues. In most developing countries, surveys show that the average desired family size is still above the level consistent with long-term replacement of the popula- 25 TABLE III.1. GOVERNMENTS VIEWS OF POPULATION GROWTH RATE, 1974-1998 (Percentage of countries) Total Number of countries 25 19 11 14 100 100 100 100 156 168 190 180 69 86 69 31 13 29 100 100 100 39 56 45 38 28 36 15 10 10 100 100 100 129 134 135 Year Too high Satisfactory World 1974 1983 1993 1998 28 36 44 41 47 45 45 44 More developed regions 1983 1993 1998 0 2 2 Less developing regions 1983 1993 1998 47 61 54 Too low Source: The Population Policy Data Bank maintained by the Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat. NOTE: Categories may not sum to the total, due to rounding. tion. However, the same surveys show that declines in desired family size are already under way in all developing regions and that currently large percentages of women are having more children than they indicate they want to have. Broader development efforts, particularly those that reduce poverty, improve women’s status and increase the education and health of the population, will create conditions that will facilitate the demographic transition by reducing mortality risks and lessening the number of children families desire to have. per cent between surveys conducted in the late 1970s or early 1980s and surveys conducted in the early 1990s. Although the average fertility level had declined by over one child per woman, the average level of unwanted fertility had actually increased. Typically, it is not until overall fertility levels have fallen substantially that the level of unwanted fertility also begins to decline. While the majority of countries in the less developed regions are concerned over their high population growth rates, an increasing number of countries in the more developed regions are expressing concern about their low rates of population growth. The proportion of Governments perceiving their growth rate to be too low, which had fallen from 25 per cent in 1974 to 11 per cent in 1993, increased to 14 per cent in 1998. This recent increase is confined to countries in the more developed regions (whose proportion of Governments perceiving their growth rate to be too low increased from 13 per cent in 1993 to 29 per cent in 1998) and is related to the very low fertility rates in some of those countries. For the period 1995-2000, the total fertility rate is below the level of 2.1 births per womanapproximately the level needed for the population to replace itself over the long termin over 90 per cent of countries in the more developed regions; it is below 1.5 births per woman in about half of the developed countries. The greatest shift in views with regard to the population growth rate between 1993 and At the same time, even without further declines in the number of children desired, there is at present a substantial potential for reducing fertility and hence population growth rates by helping couples and individuals avoid unwanted pregnancies. While there has been notable progress in making family planning information and services available, surveys continue to show a high level of unmet need for family planning in developing countries in all regions. Furthermore, levels of unwanted fertility have tended to rise even as fertility levels have begun decreasing in developing countries, as declines in the number of children desired have outpaced people’s ability to regulate their fertility. For example, a recent study of 20 developing countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean (Bongaarts, 1997; United Nations, 1998c) found that the average percentage of married women who wanted no more children had risen from 40 to 52 26 “such measures can have modest effects in raising fertility levels, but to provide economically-meaningful financial incentive to families in high-wage countries would require very substantial public expenditures” (Teitelbaum, 1997, pp. 130-131). Of course such steps may be, and frequently are, adopted by Governments as elements of policies to support family well-being, even when there is no wish to influence fertility levels. 1998 occurred among countries of the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) and in Eastern Europe. Many of the countries in the latter group considered their population growth to be satisfactory in 1993 but shifted to a view of considering it to be too low. In those cases, there is concern about stagnant or increasing mortality as well as about low levels of fertility. Many of these Governments have adopted policies to overcome the demographic slowdown through measures to increase fertility, improve health services, reduce infant and maternal mortality, and reduce the mortality of adults, especially males. In summary, rapid population growth remains a concern for a majority of Governments in developing countries, even though there have been significant recent declines in rates of population growth. The main “proximate” cause of the growth-rate declines is the increased use of effective methods of family planning, which has enabled couples and individuals to have better control over the timing as well as the number of births. Despite the progress already made in extending family planning and other reproductive health services, this revolution in reproductive choice is unfinished and in some countries has barely begun. Unwanted and mistimed births are a common occurrence. Desired family size is also declining in all developing regions. Continued and increased efforts to meet this growing need for family planning services will directly benefit couples and individuals and will also help “buy time” for the achievement of broader development goals. Fertility prospects in low-fertility countries were discussed at an expert group meeting convened by the Population Division of the United Nations Secretariat in November 1997. While the general expectation is that fertility will remain low in the more developed countries, there are differing views regarding how low and, more specifically, regarding whether fertility is likely to remain substantially below the replacement level for an extended period. Many population specialists believe that the very low levels of fertility seen in most developed countries during the 1990s are likely to rise again, as births that were delayedby rising ages at first marriage and a postponement of births to higher parental agestake place in later years. Surveys indicate that people in many developed countries would like about two children, on average. This average, if achieved, would produce fertility levels near those consistent with population replacement in the long term. However, it is also clear that many factorsincluding instability of marital unions, unfavourable economic circumstances and, particularly at higher ages, infecunditycan cause couples and individuals to have fewer children than they would have desired under ideal conditions. In some countries, especially in Eastern and Southern Europe, it is already clear that age cohorts currently nearing the end of childbearing will achieve fewer than two children on average. Thus, the long-term course of fertility in the late stages of the demographic transition remains unclear. For Governments concerned about low population growth, there are no well-tested policy recipes to follow. The coming years may therefore see increased discussion of policy alternatives, and Governments will benefit from exchanging ideas and experiences, and from continued efforts to improve understanding of the forces underlying their changing demographic circumstances. B. POPULATION AGE STRUCTURE The objectives of the Programme of Action in regard to population age structure are directed at major groups at opposite ends of the age spectrum, namely children, adolescents and youth on the one hand, and elderly persons on the other. The Programme of Action seeks to promote the health, well-being and potential of all children, adolescents and youth in accordance with the commitments made at the World Summit of Children and set forth in the Convention on the Rights of the Child, contained in General Assembly resolution 44/25, annex. The Programme of Action urges that educational programmes be guaranteed at all Historical experience provides no clear guidance for Governments seeking a balance among their demographic development, social development and economic development in the late stages of the demographic transition. Reviews of past attempts by Governments to encourage higher fertility through measures such as family allowances, tax incentives, preferences for housing and support for childcare have concluded that 27 levels, especially for girls. Beneficial effects will include reducing the number of early marriages and the incidence of high-risk childbearing and associated mortality and morbidity. An additional objective calls for the expansion of employment opportunities for young people. As concerns older persons, the Programme of Action’s objectives are to improve the selfreliance of elderly people, to develop health-care systems and social security schemes, paying special attention to women, and to enhance the ability of families to take care of elderly people within the family. The rising trend in school enrolment at all educational levels and declining trend in illiteracy are benefiting both males and females. However, improvements in sub-Saharan Africa and the least developed countries, where school enrolment ratios and literacy levels are much lower than in other countries, have been modest. Thirty-two countries still have enrolment ratios of less than 50 per 100 school-age children for primary and secondary school combined. In many countries, education continues to be characterized by high drop-out rates, very high pupil-teacher ratios and inadequately equipped school facilities. In most countries, boys have higher enrolment rates than girls, and the differences are often substantial, particularly in countries where levels of enrolment are low overall. In half of the developing countries, the enrolment ratio for boys exceeds that for girls by five points or more. However, in Latin America and the Caribbean, the gender gap in school enrolment is narrower than in the other less developed regions. In a substantial fraction of the countries of that region enrolment ratios for females are higher than for males. Owing to declining mortality levels and the persistence of high levels of fertility, a significant number of developing countries continue to have large proportions of children and young people in their populations (figure III.1). Children under age 15 currently make up 33 per cent of the population of the less developed regions and 43 per cent of the population of the least developed countries. It is projected that these figures will have declined to 20 per cent and 24 per cent respectively by 2050. Rapid growth in the number of young people and adolescents boosts demand for health-care services, education and employment, representing major challenges and responsibilities for society. To achieve the goals of the Programme of Action for 2005 and 2015 with regard to children and adolescents, as well as those of the World Summit for Children for 2000, new directions may need to be pursued. Examples may include fine-tuning national programmes, reformulating goals and strategies, according special attention to capacity-building, prioritizing goals at national, subnational and community levels, and adapting to local situations to reflect, for instance, the presence of serious epidemic diseases, such as human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), malaria, tuberculosis or other acute diseases. The world population of older persons is considerably smaller than the child population, but the older population is growing at a much faster pace. The number of persons aged 60 years or over is 580 million in 1998 and it is projected that the number will have grown to nearly 2 billion by 2050, at which time it will be larger than the population of children. Many societies, especially in more developed regions, have already attained older population age structures than any ever seen in the past. While once limited to developed counties, concern for the consequences of ageing has spread to the many developing countries which have experienced rapid fertility declines. Population ageing will have wide-ranging economic and social consequences for economic growth, savings and investment, labour supply and employment, pension schemes, health and long-term care, intergenerational transfers, taxation, family composition and living arrangements. For the older population, key issues concern their socio-economic status, productive ageing and quality of life. With respect to the population of older persons, developed countries generally have a range of policies and programmes to meet the needs of the elderly, while developing countries are less far along. Healthcare services specifically designed to deal with the needs of older persons are available in developed countries, but few developing countries have such services. Among developed countries, there has been an evident shift away from institutionalization of older 28 Figure III.1. Population pyramids: age and sex distribution, 1998 and 2050 World 1998 10 0+ 95 -9 9 90 -9 4 85 -8 9 80 -8 4 75 -7 9 70 -7 4 65 -6 9 60 -6 4 55 -5 9 50 -5 4 45 -4 9 40 -4 4 35 -3 9 30 -3 4 25 -2 9 20 -2 4 15 -1 9 10 -1 4 5- 9 0- 4 2050 Females Males 8 6 4 2 0 2 4 6 8 8 6 4 Pe rce nta ge of p op ulation 1998 2 0 2 4 6 8 6 8 Pe rce nta ge of p op ulation 2050 More developed regions 10 0+ 95 -9 9 90 -9 4 85 -8 9 80 -8 4 75 -7 9 70 -7 4 65 -6 9 60 -6 4 55 -5 9 50 -5 4 45 -4 9 40 -4 4 35 -3 9 30 -3 4 25 -2 9 20 -2 4 15 -1 9 10 -1 4 5- 9 0- 4 8 6 4 2 0 2 4 6 8 8 6 4 2 0 2 4 Pe rce nta ge of p op ulation Pe rce nta ge of p op ulation Less developed regions 1998 2050 10 0+ 95 -9 9 90 -9 4 85 -8 9 80 -8 4 75 -7 9 70 -7 4 65 -6 9 60 -6 4 55 -5 9 50 -5 4 45 -4 9 40 -4 4 35 -3 9 30 -3 4 25 -2 9 20 -2 4 15 -1 9 10 -1 4 5- 9 0- 4 8 6 4 2 0 2 4 6 8 8 6 4 Pe rce nta ge of p op ulation 1998 6 4 2 0 2 4 0 2 4 6 8 2050 Least developed countries 10 0+ 95 -9 9 90 -9 4 85 -8 9 80 -8 4 75 -7 9 70 -7 4 65 -6 9 60 -6 4 55 -5 9 50 -5 4 45 -4 9 40 -4 4 35 -3 9 30 -3 4 25 -2 9 20 -2 4 15 -1 9 10 -1 4 5- 9 0- 4 8 2 Pe rce nta ge of p op ulation 6 8 8 6 4 2 0 2 4 6 Pe rce nta ge of p op ulation Pe rce nta ge of p op ulation Source: World Population Prospec ts: The 1998 R evision, vol. II, The Sex and A ge D istribution of the World P opulations (U nited N ations publication, Sa les No. E .99.XIII.8). 29 8 persons in favour of home-care services. While programmes to support the integration of older persons into their families are gaining momentum in developed countries, they are still not common in developing countries, even though in many developing countries scant provision exists for social support outside the family. The rapid growth of older populations has not been matched by a commensurate increase in social support for the elderly in developing countries. Working women are particularly disadvantaged, as they often have the triple responsibility of labour-market activities, child-rearing and caregiving to ageing parents. ical system will be necessary, as well as the establishment and/or strengthening of geriatric training for medical personnel. For developed countries, given below-replacement fertility and future contractions in the working age population, the advisability of measures that encourage early retirement is highly questionable. A more appropriate policy in these circumstances might be to raise mandatory retirement ages and eliminate incentives to early retirement. A number of Governments are already taking steps in this direction. Although nearly all countries report the availability of pension schemes, in developing countries few of them have universal coverage. In countries with limited schemes, pension coverage is principally available to workers in the private organized sector and to government workers. In many of these countries, pension schemes are being redesigned to extend coverage to the large informal sector. Faced with varying degrees of insolvency, at least 19 countries in more and less developed regions have bolstered national pension schemes by raising the standard retirement age. There has been a growing recognition that older persons can be assisted in leading a productive life by enlarging their income-generation potential and by employment training and placement, and such assistance has become a priority at the highest levels of government. At the Denver Summit of the eight major industrialized countries in June 1997, the desire of many older persons to continue working or to be socially productive in later years was acknowledged. Among the proposed measures were removing disincentives to labour force participation, lowering barriers to flexible and parttime employment, promoting lifelong learning and voluntarism, and supporting family caregiving. C. POPULATION DISTRIBUTION, URBANIZATION AND INTERNAL MIGRATION The objectives identified in the Programme of Action are: (a) to enhance the management of urban agglomerations through more participatory and resourceconscious planning and management, review and revise the policies and mechanisms that contribute to the excessive concentration in large cities, and improve the security and quality of life of both rural and urban low-income residents; (b) to foster a more balanced spatial distribution of the population by promoting, in an integrated manner, the equitable and ecologically sustainable development of major sending and receiving areas, with particular emphasis on the promotion of economic, social and gender equity based on the respect for human rights, especially the right to development; and (c) to reduce the role of the various “push” factors as they relate to migration flows. One of the major trends at the end of the twentieth century is the growth of urban agglomerations. In mid-1998, 47 per cent of the world population lived in urban areas, which are growing three times faster than their rural counterparts. As a result, just after 2000, and for the first time in history, the number of urban-dwellers will outnumber the rural population. In regard to population ageing and the elderly, the challenge for the future is how best to allocate limited resources among public sectors. Accordingly, planning may have to reflect greater insight and sensitivity with respect to expected demographic changes. For developing countries, there is a need to move towards broad-based formal systems of income maintenance without accelerating the decline in informal systems. To achieve these dual objectives, informal support systems may have to be bolstered by offering assistance to family caregivers. Actions will also be required on the medical front. Because medical care in many developing countries has not been geared to the needs of older persons, some reorientation of the med- Even if migration is often a rational effort by individuals to seek better opportunities in life, it is also fuelled by “push” factors. These factors, such as inequitable allocation of development resources, adoption of inappropriate technologies and lack of access to available land, can be influenced by government policies. 30 Many Governments have expressed concern that high rates of rural-urban migration can hamper a city’s ability to provide all its citizens with clean water, power and waste management. As Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali said at the United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat II) held in Istanbul in 1996: “The mass exodus to cities has led to sharpened urban poverty, especially among women and dependent children, scarcity of housing and basic services, unemployment and underemployment, ethnic tensions and violence, substance abuse, crime and social disintegration. The emergence of giant megacities has brought land degradation, traffic congestion, and air, water and soil pollution” (United Nations, 1996, Introduction, fourth paragraph). for many years been shrinking. Africa is the only major area where the number of rural-dwellers is expected to continue to increase within the next three decades, by 7.25 million persons annually. In spite of the declining rate of urban population growth, the average annual increment of the world’s urban population is steadily becoming larger. While the annual increment during the period 1970-1998 was 50 million inhabitants, it is projected to increase to 74 million between 1998 and 2030. Ninety-five per cent of the 74 million urban people added annually are in the less developed regions. The giant urban agglomerations of the world, a recent phenomenon, are becoming both larger and more numerous. There were 18 cities with at least 10 million inhabitants in 1998, and their number is expected to rise to 26 by 2015. In 2015, only 4 of the 26 megacities will be located in more developed regions. While today 47 per cent of the world’s population lives in urban areas, 54 per cent will do so by 2015, and 61 per cent in 2030. In 1998, in the less developed regions, nearly two of every five persons lived in cities, whereas about three of every four persons lived in cities in the more developed regions. The gap is expected to narrow in the future, as rapid urbanization continues in the less developed regions. In 2015, 80 per cent of people in the more developed regions, 49 per cent in the less developed regions and 35 per cent in the least developed regions will live in urban areas (see figure III.2). Rural-urban migration is often viewed as the main cause of urban growth. However, the urban and rural populations of a country can change as a result of births, deaths, migration and the redefinition of urban and rural areas. Estimates of the components of urban growth derived from census data referring to 55 developing countries indicate that, excluding China, natural increasethe excess of births over deathsaccounted for about 60 per cent of urban growth in the 1960s and that its share had not declined markedly by the 1980s. Furthermore, whereas in the 1960s the contribution of natural increase to urban growth was similar in all major regions, by the 1980s it had risen to 66 per cent in Latin America and to 75 per cent in Africa. Only in Asia was there a decline in the percentage of urban growth due to natural increase but, excluding China, natural increase still accounted for 51 per cent of urban growth in Asia during the 1980s. China is exceptional in that, during the 1980s (the only period for which estimates are available), natural increase accounted for a low 28 per cent of urban growth; that is to say, the sharp fertility decline experienced by China contributed to transforming rural-urban migration and reclassification into the major components of urban growth in that country. In other regions, however, declining fertility has not yet had a similar effect and in both Africa and Latin America, achieving a lower urban fertility still has the The urban growth rate of the world, which is defined as the annual rate of change of the urban population, was 2.6 per cent annually during 1970-1990, and is projected to decline to 2.3 per cent per annum in 19952000. It is expected to decline further to have reached 2.0 per cent per annum by 2010-2015. In the less developed regions, the urban growth rate is 3.2 per cent during 1995-2000 and is projected to decline to 2.5 per cent per annum in 2010-2015. The least developed countries are characterized by both a lower proportion of population residing in urban areas and faster urban growth. Of the major geographical areas, Africa has the most rapid pace of urban growth, at 4.2 per cent per year during 1995-2000. At the same time, the rural population is still growing in most developing areas, at an average annual rate of 1.7 per cent in Africa during 1995-2000 and 0.5 per cent in Asia. In Latin America and the Caribbean as a whole, the rural population is no longer growing, while in the more developed regions the rural population has 31 Figure III.2. Percentage of population residing in urban areas, 1970, 1998, 2015 and 2030 Source: World Urbanization Prospects: The 1996 Revision (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.98.XIII.6), special tabulations. potential of significantly reducing the growth of the urban population. oped regions, considered their patterns of population distribution to require major change. Twenty-nine per cent of all countries, 71 per cent of which are in less developed regions, desired minor changes in their patterns of population distribution. Issues of population distribution featured prominently not only at the International Conference on Population and Development, but also at the United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat II) held, in Istanbul in June 1996 and, as regards the rural population, at the World Food Summit, held in Rome in November 1996. The analysis of internal migration in developing countries has often been limited to the consideration of rural-urban migration; but for most of the countries for which data are available, rural-urban migration is not the flow accounting for the largest proportion of internal movements. Indeed, in countries that are still largely rural, rural-rural migration is likely to be more important than rural-urban migration (as is the case in Ethiopia, India and Thailand); whereas in countries that are highly urbanized, urban-urban migration will dominate (as is the case in the Republic of Korea in the 1990s, Brazil and Peru). Unfortunately, only a few countries have consistently gathered information allowing an assessment of the different types of flows. The data available indicate that the propensity to migrate is higher among the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean than among those of Asia. In many developing countries, population distribution policies are largely synonymous with measures to reduce or even block rural-urban migration. In practice, most policies aimed at slowing the growth of large metropolitan areas have been ineffective. Even in centrally planned economies, such as China’s, which for years has utilized residential controls, there are large “floating” populations of unauthorized migrants in all of the major cities. Although there is a broad consensus among Governments in the developing world concerning the desirability of promoting small and medium-sized cities, how to achieve this goal is less clear. Regional development policies for In 1998, only 27 per cent of countries in the world considered their patterns of population distribution to be satisfactory (see table III.2). In contrast, 44 per cent of all countries, 87 per cent of which are in less devel- 32 TABLE III.2. GOVERNMENTS’ VIEWS ON SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION, BY LEVEL OF DEVELOPMENT AND MAJOR AREA, 1998 (Number of countries) View Satisfactory Minor change Major change Total desired desired A. By level of development World 49 More developed regions 21 Less developed regions 28 Of which least developed countries 6 B. By major area Africa 6 Asia 8 Europe 19 Latin America and the Caribbean 10 Northern America 2 Oceania 4 52 14 38 12 78 9 69 29 179 44 135 47 13 15 12 7 0 5 33 17 8 16 0 4 52 40 39 33 2 13 Source: Population Policy Data Bank maintained by the Population Division of the United Nations Secretariat. lagging regions, border-region strategies and land colonization schemes have also been employed in a number of developing countries, but the impact of those policies on national population redistribution has been almost negligible. Whereas there remains a considerable knowledge gap with regard to the complexity and future implications of demographic change in the world’s megacities, there is now a generally accepted body of ideas with respect to policy, and the debate about this topic has become less ideological. In the 1960s and 1970s, there had been an urban bias of planners and many Governments. However, during the 1980s and early 1990s, it is not too strong to state that there was an anti-urban bias of many scholars involved with the topic. Both biases have dissipated. It is widely acknowledged that cities are, in general, productive places which make more than a proportionate contribution to economic growth. Moreover, a limited number of big but well-managed cities may put less pressure on the environment than a larger number of smaller cities. City size per se is not a critical variable. The size is not necessarily correlated with the severity of its negative externalities. The key challenge is to manage megacity growth efficiently. Partially in response to the ineffectiveness of the growth-centre strategies pursued by many developing countries during the 1960s and early 1970s, many countries have adopted strong rural-oriented spatial policies. Rural development strategies are critically important in developing countries for expanding food production and improving agricultural productivity, and consequently they may reduce push factors and migration patterns. However, there is little evidence of their total effect on rural-urban population flows. In recent years, many Governments have abandoned direct policies to control population distribution and adopted policies that seek to work alongside market forces. The idea behind this approach is to create a “level playing field”, in other words, to provide infrastructure in under-served areas in order to channel private investment into designated regions. Chile, for example, reports that it intends to charge those who can afford it, market prices for urban services, thereby eliminating subsidies that serve as an indirect incentive for rural-urban migration. Salary differentials for public officials by area of residence, and targeted use of housing investments, tax rebates, subsidies, technical assistance and so forth, are also seen as having significant potential spatial impacts. The Programme of Action recommends that Governments increase the capacity and competence of city and municipal authorities to manage urban development. In this regard, they may wish to consider decentralizing their administrative systems. This also involves giving the right to raise revenue and allocate expenditures to regional districts and local authorities. Such steps can increase the ability of local authorities to safeguard the environment, to respond to the need of all citizens for personal safety and services, 33 and to eliminate health and social problems, including problems of drugs and crime. Governments, as well as non-governmental organizations, can contribute to the welfare of the urban poor by helping to develop their income-earning ability. The Istanbul Declaration and the Habitat Agenda on Human Settlements (United Nations, 1997b, chap. I, resolution 1, annexes I and II), adopted in 1996, contain additional commitments and strategies for achieving adequate shelter for all and making human settlements safer, healthier and more liveable, equitable, sustainable and productive. World Summit for Social Development (1995), the Fourth World Conference on Women (1995), the United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat II) (1996), the World Food Summit (1996) and, most recently, the nineteenth special session of the General Assembly held in 1997 to review progress in the implementation of Agenda 21 (United Nations, 1993, resolution 1, annex II), have stressed the interrelatedness of the major environmental, development and social concerns with population issues (see box III.1). These conferences and summits have helped to reinforce the conclusion from the Programme of Action that efforts to slow down population growth, to reduce poverty, to achieve economic progress, to improve environmental protection and to reduce unsustainable consumption and production patterns are mutually reinforcing and that slower population growth can buy more time for countries to build the base for future sustainable development. Governments wishing to create alternatives to outmigration from rural areas should improve rural education infrastructure, health and other social services. Equitable rural development can be further promoted through legal and other mechanisms, as appropriate, that advance land reform, recognize and protect property, water and user rights, and enhance access to resources for women and the poor. There is also a need for effective systems of regional planning and decision-making, ensuring the wide participation of all population groups. The Programme of Action also urges countries to recognize that the lands of indigenous people and their communities should be protected from activities that are environmentally unsound or activities that the indigenous people concerned consider to be socially and culturally inappropriate; in many places, there is a continuing need for effective steps to ensure such protection. With respect to the wide range of environmental, social, health and economic goals set out in the Programme of Action and at other global conferences, progress has been mixed. Overall progress has been made, though with setbacks in some countries and regions, towards reducing poverty rates (though not as yet the absolute number of the poor), increasing food supplies and improving health and education. The Programme for the Further Implementation of Agenda 21, adopted in 1997 and contained in the annex to General Assembly resolution S-19/2 of 28 June 1997, noted particularly recent declines in the global rate of population growth as among the positive trends since Agenda 21 had been adopted in 1992. D. LINKAGES BETWEEN POPULATION AND DEVELOPMENT The Programme of Action aims to fully integrate population concerns into development, environmental and poverty-reduction strategies and resource allocation at all levels, with the objectives of meeting the needs and improving the quality of life of present and future generations, promoting social justice and eradicating poverty through sustained economic growth in the context of sustainable development. Even though poverty rates have declined dramatically in many countries in recent years, progress has been uneven. Over 1.3 billion people are still classified as poor, and the economic downturn that began with the Asian financial crisis in 1997 has reversed some of the gains. It is widely believed that the most important factor accounting for poverty is the macroeconomic environment, and especially factors that govern the growth of employment. The period since the early 1990s has been, with some notable The objectives of the International Conference on Population and Development in these areas are shared with other recent global conferences and summits. The 34 Box III.1. Excerpt from the Programme for the Further Implementation of Agenda 21 a Population The impact of the relationship among economic growth, poverty, employment, environment and sustainable development has become a major concern. There is a need to recognize the critical linkages between demographic trends and factors and sustainable development. The current decline in population growth rates must be further promoted through national and international policies that promote economic development, social development, environmental protection, and poverty eradication, particularly the further expansion of basic education, with full and equal access for girls and women, and health care, including reproductive health care, including both family planning and sexual health, consistent with the report of the International Conference on Population and Development. ______________ a General Assembly resolution S-19/2, annex, para. 30. exceptions including the economies in transition, a period of generally robust economic growth. However, the recent financial crisis shows that sustained progress cannot be taken for granted and that in today’s economy the ramifications of a national or regional financial crisis can quickly spread throughout the globe. pirical studies failed to find evidence of strong or consistent relationships between demographic change and subsequent economic growth. However, recent assessments have revealed fairly large negative associations between rapid population growth, and its associated demographic components, and growth rates of per capita output, based on data for the 1980s or later and for the entire period from the 1960s through the early 1990s. The negative effect of high fertility on economic growth also appears greater for poorer countries. At present, this is an area of active research work, where models and results are still emerging and conclusions are preliminary. Furthermore, analysts stress that realizing the potential benefits requires an economic and political climate in which potential workers can be productively employed, and where potential savings are channelled into productive investments. While population factors cannot account for shortterm economic fluctuations, there has been persistent interest in population’s possible economic effects in the longer run. The predominant view in recent years, as reflected in the Programme of Action, is that slower rates of population growth can buy more time to adjust and can increase countries’ ability to attack poverty, protect and repair the environment and build the base for future sustainable development. During the past several years, analysts have renewed directing attention to one aspect of population change, namely, the possible economic implications during the demographic transition of the age-structural effects of declining fertility. After a lag, lower fertility leads to an increased proportion of the population in the working ages which, it has been proposed, should favour economic growth: resources freed from care for a larger child population could be productively directed towards increased labour force participation (especially among women) and towards increased investment in both physical and human capital, thereby speeding economic development. The importance of such effects was, however, called into question, as earlier em- World food production per capita has increased by more than 20 per cent over the period 1961-1996. The most rapid increase has been in the developing countries where population more than doubled and daily food calories available per person rose from roughly 1,900 to 2,600 calories. The general consensus (with few exceptions) from the recent research literature is that, with a steady increase in the prudent management of food-producing resources and with an improved and reasonably well-functioning institutional environment, it should be possible to meet food needs in the foreseeable future. These assessments take into account, 35 and are conditioned by, the projected slowing and eventual stabilization of world population; all assessments recognize that food needs are linked to population size. Despite these grounds for cautious optimism, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimates that over 800 million people today do not have enough food to meet their basic nutritional needs. Although the percentage of the undernourished is estimated to have declined slightly between 1990-1992 and 1994-1996, their absolute number increased. There are important issues relating to problems associated with food distribution within and between countrieslargely matters of augmenting “entitlements” to the very poor; creating public-policy environments and rural infrastructure, including research and development, education and health, that facilitate agricultural production; and encouraging strategies of environmentally-friendly, sustainable production. Furthermore, as stated in the Rome Declaration on World Food Security (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1996, appendix), “a peaceful, stable and enabling political, social and economic environment is the essential foundation which will enable States to give adequate priority to food security and poverty eradication” (fourth paragraph). The growth and distribution of the population have direct impacts on the environment, but the nature of these impacts is largely governed by institutional realitiesproperty rights, land distribution, taxes and subsidies on various types of production and consumption, and the like. Given the nature of environmental resources, government policies are critical to population-environmental interactions. Many Governments view population size or trends as a factor contributing to national environmental problems. Especially in developing countries, population’s role is often viewed as a serious concern. The urban environment and the adequacy of water supplies (both amount and quality) are the environmental areas where populations impact is most often seen as serious. Rarely, however, do Governments seek a solution to environmental problems solely through altering population trends or distribution. In many cases though, Governments report a policy approach that combines measures to affect population with other approaches to alleviating environmental problems. During the 1990s, many Governments have been reevaluating and reforming their mechanisms for development planning, and in many areas there has been a shift from central planning to a greater reliance on market forces and the private sector. A crucial task in this transition is to identify the areas in which the State must continue to safeguard the interests of the disadvantaged “and the generations yet to be born that would be likely to lose out, if the markets were to become absolute arbiters of their fate” (Visaria, 1998). While non-governmental organizations and the private sector can and should play an important role, government commitment, support and leadership at the local, regional and national levels remain critical for halting and reversing damage to the environment and for provision of primary and secondary education, primary health care and other basic social services, especially for the poor. Environmental trends are much less encouraging. The special session of the General Assembly in 1997 to assess progress with respect to Agenda 21 concluded that “five years after the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, the state of the global environment has continued to deteriorate ... Some progress has been made in terms of institutional development, international consensus-building, public participation and private sector actions and, as a result, a number of countries have succeeded in curbing pollution and slowing the rate of resource degradation. Overall, however, trends are worsening” (Programme for the Further Implementation of Agenda 21, para. 9). 36