Health Sector Reforms in Nigeria and the impact on poverty reduction

advertisement

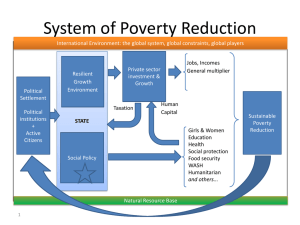

HEALTH SECTOR REFORMS IN NIGERIA AND THE POTENTIAL FOR POVERTY REDUCTION* Introduction Nigeria faces a number of development challenges, of which poverty holds a central place. Indeed, the country is a land of paradox inasmuch as poverty is concerned. While Nigeria is a leading oil-producing nation and highly endowed in terms of various natural resources, the majority of her people are economically poor. As recent national data shows, over one-third of Nigerians (35%) live in extreme poverty while 54% are relatively poor. More than half of the Nigerian population live on less than a dollar a day.1 In view of the extent and depth of poverty in the land, it should not be surprising that the health status of the country is poor, with an average life expectancy of only 46.6 years2. According to the 2008 Human Development Report Nigeria is in the low human development index category and ranks 154 out of 179 countries, behind some West African countries with less economic potentials such as Ghana, Cameroon, and Senegal, which are in the medium human development category2. Poverty has a strong link and two-way relationship with health: poverty makes people more vulnerable to ill-health, and ill-health tends to lead to poverty. Hence, as the common saying, “Health is wealth”. Among others, the poor are more likely to experience ill-health as a result of several factors, which include poor diet and poor living conditions, and when they are ill they are less likely to access health care services because of inability to pay. The poor in Nigeria are more likely to be found in the relatively deprived rural areas and peri-urban slums, where high quality health services are often lacking. On the other hand, ill health affects productivity, and therefore, reduces income and also tends to wipe away savings and diminish ability to invest. Thus, ill * Dr. Adesegun Ola. Fatusi Department of Community Health Faculty of Clinical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria adesegunfatusi@yahoo.co.uk health and poverty reinforce one another, and compromise quality of life and longevity. Indeed, the poor are more likely to die young. Poverty can indeed be described as the leading global health challenge and “disease” in view of its ubiquitous effects on the health status of individuals and communities in the world. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), “The world’s biggest killers and the greatest cause of ill-health and suffering across the globe is extreme poverty. Poverty is the main reason why babies are not vaccinated, why clean water and sanitation are not provided, why curative drugs and other treatments are not available and why mothers die in childbirth3. Thus, efforts to address poverty must necessarily consider health sector input, while efforts to improve health must also be seen from its poverty reduction potential. The Federal Government of Nigeria had launched the Health Sector Reform (HSR) as a major initiative to improve the health and well-being of the citizens. This article discusses the Nigerian health sector reform and its implications for poverty reduction. . Health Sector Reform: Rationale and Process Reform means positive change. But health sector reform implies more than just any improvement in health or health care. It is a process motivated by the need to address fundamental deficiencies in health care systems that affect all health care services. Health sector reform has been defined as “a sustained process of fundamental change in policy and institutional arrangements, guided by government, designed to improve the functioning and performance of the health sector, and ultimately the health status of the population”4. A committee of the WHO African region defined it as “a sustained process of fundamental change in policy, regulation, financing, provision of health services, reorganisation, management and institutional arrangements that is led by government and designed to improve the performance of a health system to attain a better health status for the population5. Drawing from the work of Berman, it can also simply be said to be a “sustained and purposeful change to improve the efficiency, equity and effectiveness of the health sector”6. “Sustained” in the sense that it is not a "one shot" temporary effort that will not have enduring impacts; and, “purposeful” in the sense of having a rational, planned basis - to improve health system performance in terms of well-defined outcomes. HSR can also be described as “Strategic” in the sense of addressing significant, fundamental dimensions of health systems. In the case of Nigeria, the argument for HSR is based on the poor health status of the population and the poor rating of the health system itself. Nigeria’s health system, for example, was ranked 187 out of 191 countries by WHO in 2000. The infant mortality ratea, the under-five mortality rateb and the maternal mortality ratioc are some of the indicators that are often used to compare health status of populations. Nigeria’s figures on each of the three indices are some of the worst in the world, even by the standard of developing countries. Currently, a tenth of children born in Nigeria die under the age of one year (Infant mortality rate of 100 per 1000 live births) and a fifth die before their fifth birthday (under-five mortality rate of 201 per 1000 live births) 7. According to the most recent estimates from United Nations agencies, over 50,000 mothers die from childbirthrelated events – the second highest annual national maternal deaths figure in the world. Nigeria’s maternal mortality ratio is estimated to be between 800 and 1,000 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. Furthermore, the leading causes of deaths among mothers and children in Nigeria are largely preventable health problems or easily treatable ones. For children, these include vaccine preventable diseases (polio, diphtheria, whooping cough, tetanus, and measles), malaria, and diarrhea. The situation clearly suggests that the Nigerian health system needs more than a cosmetic change - what it requires is a radical reform to improve its performance8,9. In the words of Professor Adetokunbo Lucas, an eminent public health physician, “The Nigerian health system is sick, very sick and in need of intensive care.”10 As a Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) documents puts it, the Nigerian health “system is so complex and has grown out of so many obtuse ‘needs’ that the best approach to reform is to start afresh and plan the system de novo”.11 a Infant mortality rate: Number of children that die under the age of 1 year per 1000 live births. b Under-five mortality rate: Number of children that die under the age of 1 year per 1000 live births. c Maternal mortality ratio: The number of maternal deaths per 100 000 live births. HSR is an inherently political process, and it is often implemented on a sector-wide level. Initiatives to reform the health system has been attempted at various times in the history of the health development of the country, with a view to substantially improve the system to perform the three fundamental objectives of a health system, viz. Improve the health of the population they serve, provide financial protection against the cost of ill-health, and respond to people’s expectation12. A discussion of the various initiatives is beyond the scope of the present paper, rather the focus is on the most recent effort – the HSR initiated in 2004 during the second term of the President Olusegun Obasanjo, with Professor Eyitabo Lambo as the Federal Minister of Health. The HSR was one of the social sector reforms undertaken by the Obasanjo administration, with the National Economic Empowerment Development Strategy (NEEDS) providing the overall national development framework. The NEEDS, itself, has four major goals: wealth creation, poverty reduction, employment generation and value re-orientation. The development of the HSR implementation document entailed a participatory and consultative approach with inputs from various stakeholders in the health sector, including the National Council on Health. The mission statement regarding the HSR was “to undertake a government-led comprehensive health sector aimed at strengthening the national health system to enable it deliver effective, efficient, qualitative and affordable health services and thereby improve the health status of Nigerians as health sector’s contribution to breaking the vicious circle of ill-health, poverty and under-development”. This suggests that the initiators and the drivers of the reform process clearly recognized the inter-relationship between poverty and ill-health and understand the potential of the HSR to contribute to poverty reduction in the country. In fact, one of the underlying assumptions and cross-cutting principles for the HSR programme is the belief “that ill-health is a major determinant of poverty. Thus, addressing the health needs of all Nigerians is an important component of the country’s poverty reduction strategy”. The Contributions of the Health Sector Reform Process While hard data is not available to assess the contributions of the HSR to poverty reduction presently, a close scrutiny and an analysis of its provision and the implementation process will provide insights into its potentials in this respect. The HSR has the following strategic thrusts: Improve the performance of the stewardship role of government Strengthen the national health system and improve its management Improve availability of health resources and their management Improve the access (including physical and financial) to quality health services Reduce the disease burden attributable to priority health problems Promote effective public-private partnership in health Increase consumers’ awareness of their health rights and health obligations. Thus, these thrusts address the issues of payment, financing, organization, regulation, and behavior - which are fundamental to health system performance. Within each of the strategic thrusts for the reform programme, a number of priority health sector performance issues have been identified for focused interventions, because of their presumed sector-wide catalytic effects. These thrusts have been carefully selected and priority actions outlined such that the implementations of relevant activities will logically lead to improved health outcomes. The priority areas include the following: reduced disease burden (with major focus on HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and vaccinepreventable childhood diseases), reduction in child mortality and morbidity, improved maternal health, and increased life expectancy (Figure 1) through improved health behaviours and improved service provision. The selection of priority activities was made on evidence-based platform, taking into consideration the contribution of each group of health problem to the overall health status of Nigerian and the cost-effectiveness of available interventions. Overall, the priority focus was on the diseases and health problems that are responsible for most morbidities and mortalities among Nigerian population groups. This is with the desire to positively impact the greatest number of people within the shortest possible time. Such an approach has the potentials to positively affect the landscape of health and wellness of the population such that they can be more health to pursue their productive enterprises and earn improved incomes Also, the money that would otherwise have been spent on ill-health and hospital bills can be used to improve the nutrition and general living condition of individuals and households, as well as improve savings and investment – all of which would contribute to poverty reduction. The case of malaria as covered under the strategic thrust of “Reducing the disease burden attributable to priority health problems provides a good illustration of how the reform process could reduce poverty. Malaria is a leading cause of death among children and also have negative impact on the outcome of pregnancy, including premature delivery and delivery of low birth babies. Malaria also causes blood shortage (anaemia) in pregnant women. In addition, malaria reduces productivity in all ages, thereby contributing to decreased academic performance of school children and lower earning of the adult. Under the reform process, and based on evidence of cost-effectiveness impact, the strategy is to particularly address malaria through preventive measures such as provision of insecticide-treated bed nets. Specific drugs are also to be provided to pregnant women as part of routine antenatal care to prevent malaria. As Figure 2 depicts, this, in turn, will result in improved delivery outcome and healthier babies. These children will experience fewer episodes of malaria as they sleep under bed nets and the family will therefore spend less on health problems (in terms of money and time). In turn, there will be greater possibility of savings and investment, which will ultimately reduce the potential for poverty. Other strategies such as education of mothers to treat simple childhood health problems, recognize danger signs, and seek treatment early will also complement the preventive strategies such that even if the child develop malaria, he or she can be treated at the early stage to ensure early recovery. Overall these strategies will lead to healthier adults, conceptually, with capacity for maximal productivity. Some of the progress that have been made in the implementation of the HSR agenda include increased coverage of preventive interventions such as insecticide-impregnated as well as the provision of free artemisinin-based combination therapies to treat malaria in children, and improved access to HIV testing facilities and anti-retroviral therapy. There has also been an increase in the access to vaccines to protect children from major killer diseases. The enactment of the National Health Insurance Services Act deserves special mention. The scheme, though limited in coverage to workers in the formal sector at present, has improved access to services. Increased resources have also been provided towards the achievement of the health-related Millennium Development Goals, such as those targeting child and maternal health, and the control of HIV/AIDS and malaria. Efforts to improve quality through enforcement of consumers’ rights and improving health behaviour through behaviour change interventions are also ongoing. While the implementation of these and other activities may not translate directly to improved health outcomes, they certainly have the potentials to contribute to improved health in Nigeria substantially. Conclusions The on-going health sector reform has various provisions that could make for improved health outcomes through improved health behaviour and improved quality of health service delivery. These are expected to impact on poverty because of the strong linkage between poverty and health. While the implementation rate of the HSR, though not optimal, gives some reasons to cheer, it is important to note that the expected health development outcomes will ultimately prove elusive except the carefully chosen priority actions outlined in the HSR documents are pursued vigorously, relentlessly and faithfully. The implementation strategy and rates need to be carefully monitored in this wise. Thus, the HSR has the potential as a health system intervention to break the vicious cycle of ill-health, poverty and under-development through improved health outcome and translate it into a virtuous cycle of improved health status, prosperity and sustainable development. Figure 1d Strategic Framework for Improving Health Outcomes through HSR CONTEXT NEEDS, MDGs, Health Systems Performance Public Service Reform PROCESS Stakeholders’ Consultation Consensus Building STRATEGIC THRUSTS Improving the stewardship role of Government Strengthening the National Health System and its Management Reducing Disease Burden Improving availability of health services Improving access to quality health services Improving consumer awareness of their health rights and obligation Promoting effective public-private partnership CHANGE IN HEALT H PROGRAM AND SERVICES Improving Health Care Financing Improved Human Resources Management Improved Health Care delivery, Improved procurement & supply Improved access to health information & communication d CHANGES IN HEALTH SYSTEMS PERFORMANCE Improved access, equity, efficiency, performance and sustainability of the health system CHANGES IN UTILISATION OF SERVICES Improved health seeking behaviour Improved knowledge attitude and practices Improved health promotion activities Improved access to information HEALTH OUTCOMES Reduced Disease Burden (HIV/AIDS, TB, MALARIA, VPD) Reduction in Child Mortality and Morbidity Improved Maternal Health Improved Life Expectancy Adopted from Lambo E. Health sector reform in Nigeria: The journey so far. Presentation at the National Health Conference, Abuja, 28t - 29th 2006, pp.173-184 Figure 2 Potential Effect of Malaria Control on Poverty Reduction Implementation of HRS measure against malaria Reduced malaria related incidence in children Reduced Child death Reduced malaria related incidence Reduced spending on illness Reduced negative maternal & Child outcome Healthier Children… Increased family saving & investment Healthy Adults High level of productivity & Income Improved economic wellbeing & reduced poverty level References 1 National Bureau of Statistics. Poverty Profile for Nigeria. 2005, Abuja. 2 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Human Development Indices. 2007/2008 Human Development Report. New York, UNDP. 3 World Health Organisation (WHO). The World Health Report 1995: Bridging the Gaps. Geneva, WHO, 1995. 4 Sikosana, PLN, Dlamini, QQD, Issakov, A. 1997. Health sector reform in sub-Saharan Africa. A review of experiences, information gaps and research needs. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. 5 World Health Organisation. Definition adopted by the Regional Committee. 1999. Brazzaville, WHO African Region. 6 Berman, Peter. Health Sector Reform: Making Health Development Sustainable. In Peter Berman, ed. Health Sector Reform in Developing Countries: Making Health Development Sustainable. 1995 Boston: Harvard University Press (13-33). 7 National Population Commission Nigeria. 2004. The 2003 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey. Calverton, Maryland: National Population Commission and ORC Macro DHS 8 Lucas AO. Keynote address. In: Health care in Nigeria: Present status, future goals. Proceedings of the Sixth Obafemi Awolowo Dialogue. Ikenne: Obafemi Awolowo Foundation, 1998, pp. 9-32 9 Akande EO. Health sector reforms in Nigeria. In: Akinkugbe O & Oyediran K: The Sinews of success. Essays in honour of Kayode Osuntokun. Ibadan, The Benjamin Kayode Osuntokun Foundation, 2005, pp. 155-168. 10 Lucas, AO. National Health Conference: Chairman’s opening remarks. In: Nigeria National Health Conference 2006. Health in Nigeria in the 21st century: sustaining the reforms beyond 2007. Details of Proceedings. Abuja, Health Reform Foundation of Nigeria.2006, Pp. 4-7. 11 12 FMOH: Health Sector Reform. Priorities for Action (Outline), pg. 4 World Health Organisation. World Health Report 2000. Health Systems: Improving Performance. Geneva, WHO, 2000.