POOR ECONOMICS

advertisement

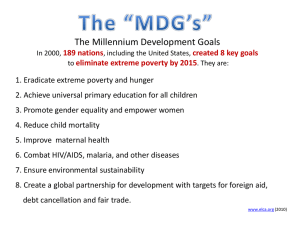

POOR ECONOMICS 1. Think Again, Again 1213015 加藤栞 ・Every year, 9 million children die before their fifth birthday. ・A woman in sub-Saharan Africa has a one-in-thirty chance of dying while giving birth-in the developed world, the chance is one in 5,600. ・There are at least twenty-five countries, most of them in sub-Saharan Africa, where the average person is expected to live no more than fifty- five years. ・In India alone, more than 50 million school-going children cannot read a very simple text. This is the kind of paragraph that might make you want to shut this book, and, ideally, forget about this whole business of world poverty: The problem seems too big, too intractable. Our goal with this book is to persuade you not to. A recent experiment at the University of Pennsylvania illustrates well how easily we can feel overwhelmed by the magnitude of the problem. Researchers gave students 💲5 to fill out a short survey. They then showed a flyer and asked them to make a donation to Save the Children, one of the world’s leading charities. There were two different flyers. Some students were shown this: →Food shortages in Malawi are affecting more than 3 million children; In Zambia, severe rainfall deficits have resulted in a 42% drop in maize production from 2000. As a result, an estimated 3 million Zambians face hunger; Four million Angolans – one third of the population – have been forced to flee their homes; More than 11 million people in Ethiopia need immediate food assistance. Other students were shown a flyer featuring a picture of a young girl and these words: →Rokia, a 7 – year – old girl from Mali, Africa is desperately poor and faces a threat of severe hunger or even starvation. Her life will be changed for the better as a result of your financial gift. With your support, and the support of other caring sponsors, Save the Children will work with Rokia’s family and other members of the community to help feed her, provide her with education, as well as basic medical care and hygiene education. The first flyer raised an average of 💲1.16 from each student. The second flyer, in which the plight of millions became the plight of one raised 💲2.83. The students, it seems, were willing to take some responsibility for helping Rokia, but when faced with the scale of the global problem, they felt discouraged. Some other students, also chosen at random, were shown the same two flyers after being told that people are more likely to donate money to an identifiable victim than when presented with general information. This book is an invitation to think again, again: to turn away from the feeling that fight against poverty is too overwhelming and to start to think of challenge as a set of concrete problems that, once properly identified and understood, can be solved one at a time. Jeffrey Sachs, adviser to he United Nations, director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University in New York City, and one such expert, has an answer to all these questions: Poor countries are poor because they are hot, infertile, malaria infested, often landlocked; this makes it hard for them to be productive without an initial large investment to help them deal with these endemic problems. But they cannot pay for the investments precisely because they are poor – they are in what economics call a “poverty trap.” Both (William Easterly, who battles Sachs from New York University and Dambia Moyo, an economist who previously worked at Goldman Sachs and at the World Bank) argue that aid does more bad than good: It prevents people from searching for their own solutions, while corrupting and undermining local institutions and creating a self- perpetuating lobby of aid agencies. There are in fact answers… it is just that they are not kind of sweeping answers that Sachs and Easterly favor. This book will not tell you whether aid is good or bad, but it will say whether particular instances of aid did some good or not. But in truth, aid is only a very small part of the money that is spent on the poor every year. Most programs targeted at the world’s poor are funded of their country’s own resources. India, for example, receives essentially no aid. In 2004 – 2005, it spent half a trillion rupees (💲31 billion USD PPP) just on primary – education programs for the poor. Even in Africa, where foreign aid has a much more important role, it represented only 5.7 percent of total government budgets in 2003. More important, the endless debates about the rights and wrongs of aid often obscure what really matters: not so much where the money comes from, but where it goes. To take an examples, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), malaria caused almost 1 million deaths in 2008, mostly among African children. One thing we know is that sleeping under insecticide-treated bed nets can help many of these lives. Studies have shown that in areas where malaria infection is common, sleeping under an insecticide-treated bed net reduces the incidence of malaria by half. For approximately 💲10, you can deliver an insecticide-treated net to a family and teach the household how to use it. Because malaria is contagious, if Mary sleeps under a bed net, John is less likely to get malaria – if at least half the population sleeps under a net, then even those who do not have much less risk of getting infected. Given the benefits both to the user and others in the neighborhood, selling the nets at a discount or even given them away would seem to be a good idea. Easterly and Moyo object, arguing that people will not value (and hence will not use) the nets if they get them for free. The shift from broad general questions to much narrower ones has another advantage. Answering these questions, we get to understand what, if anything, is special about the poor. It is the body of knowledge that grows out of each specific answer and the understanding that goes into those answers that give us the best shot at, one day, ending poverty. This book builds on that body of knowledge. A lot of the material that we will talk about comes from RCTs conducted by us and others, but we also make use of many other types of evidence. The message of this book, however goes well beyond poverty traps. As we will see, ideology, ignorance, and inertia – the three Is – on the part of expert, the aid worker, or the local policy maker, often explain why policies fail and why aid does not have the effect it should. We hope to persuade you that our patient, step-by-step approach is not only a more effective way to fight poverty, but also one that makes the world a more interesting place. Thank you!!