Common Industrial Chemicals In Tiny Doses Raise Health Issue

advertisement

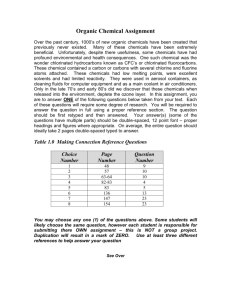

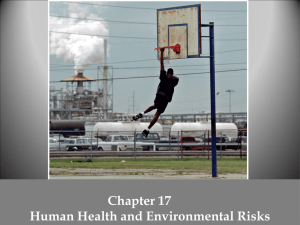

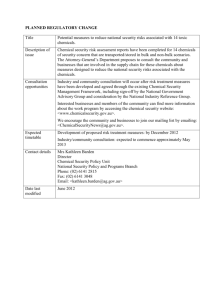

Common Industrial Chemicals In Tiny Doses Raise Health Issue Advanced Tests Often Detect Subtle Biological Effects; Are Standards Too Lax? Getting in Way of Hormones PETER WALDMAN / Wall Street Journal 25jul2005 Levels of Risk For years, scientists have struggled to explain rising rates of some cancers and childhood brain disorders. Something about modern living has driven a steady rise of certain maladies, from breast and prostate cancer to autism and learning disabilities. One suspect now is drawing intense scrutiny: the prevalence in the environment of certain industrial chemicals at extremely low levels. A growing body of animal research suggests to some scientists that even minute traces of some chemicals, always assumed to be biologically insignificant, can affect such processes as gene activation and the brain development of newborns. An especially striking finding: It appears that some substances may have effects at the very lowest exposures that are absent at higher levels. Some scientists, many of them in industry, dismiss such concerns. But the new science of low-dose exposure is challenging centuries of accepted wisdom about toxic substances and rattling the foundation of environmental law. Modern pollution restrictions aim to limit exposures to levels past studies have found safe. For example, it's known mercury can cause learning problems in children if it's above 58 parts per billion in the bloodstream. Dividing 58 by 10 to provide a margin of safety, U.S. regulators advise that children and young women not accumulate more than 5.8 parts per billion of mercury, by limiting consumption of certain fish such as tuna. But what if it turned out some common substances have essentially no safe exposure levels at all? That was ultimately what the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency concluded about lead after studying its effects on children for decades. Indications some other chemicals may have no safe limits have led regulators in Europe and Japan to bar the use of certain compounds in toys and in objects used to serve food. In the U.S., federal scientists are devising new tests that could be used to screen thousands of common chemicals to make sure they're safe at extremely low exposures. Using advanced lab techniques, scientists have found that with some chemicals, traces as minute as mere parts per trillion have biological effects. That's one-millionth of the smallest traces even measurable three decades ago, when many of today's environmental laws were written. With some of these chemicals, such trace levels exist in the blood and urine of the general population. Some chemical traces appear to have greater effects in combination than singly, another challenge to traditional toxicology, which tests things individually. EXPOSURE MILESTONES Research findings on the effects of bisphenol A (BPA) contrasted with EPA guidelines Daily dose in milligrams per kilogram of body weight. 1988 0.05 mg EPA's predicted safe dose for humans 1997 0.002 mg Linked to enlarged prostate in male mice 1999 0.0024 mg Linked to early puberty in female mice 2003 0.0002 mg Linked to altered sperm in male rats Relative Size Comparison Scientists have found effects on rodents from steadily smaller exposures to some chemicals, such as Bisphenol A, used in food-can linings and polycarbonate plastic. Source: scientific articles. The human body is complex, and effects seen in tests on small laboratory animals and in human cells don't necessarily mean health risks to people. "The question is what do we do about these low levels once we know they're there," says Steve Hentges of the American Plastics Council, a trade association. For their part, companies and industry groups have attacked low-dose research as alarmist and are challenging the findings with scientific studies of their own. Some industry studies have contradicted the low-dose findings of university and government labs. One reason, says Rochelle Tyl, a toxicologist who does rodent studies on contract for industry groups, is that academics seek "to find out if a chemical has an intrinsic capacity to do harm," while industry scientists try to measure actual dangers to people. The result is that low-dose research has sparked a number of heated scientific and regulatory controversies: Tiny doses of bisphenol A, which is used in polycarbonate plastic baby bottles and in resins that line food cans, have been found to alter brain structure, neurochemistry, behavior, reproduction and immune response in animals. Makers and users of the chemical maintain, citing a Harvard review of 19 studies, that the chemical is harmless to humans at such levels. (See illustration above) Minute levels of phthalates, which are used in toys, building materials, drug capsules, cosmetics and perfumes, have been statistically linked to sperm damage in men and genital changes, asthma and allergies in children. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has detected comparable levels in Americans' urine. Manufacturers say there is no reliable evidence that phthalates cause any health problems. A chemical used in munitions, called perchlorate, is known to inhibit production of thyroid hormone, which children need for brain development. The chemical has been detected in drinking-water supplies in 35 states, as well as in fruits, vegetables and breast milk. The EPA has spent years mulling what is a safe level in drinking water. The Defense Department and weapons makers maintain it is harmless at much higher doses than those that Americans ingest. The weed killer atrazine has been linked to sexual malformations in frogs that were exposed to water containing just 1/30th as much atrazine as the EPA regards as safe in human drinking water. The herbicide's main manufacturer, Syngenta AG, says other studies prove atrazine is safe. The EPA favors more study. In The Laboratory Studies have linked some common chemicals with toxic effect, though not necessarily at levels to which humans are exposed: What's it Chemical What's it in linked to ----------------------------------------------------Bisphenol A Polycarbonate Altered brain, (BPA) plastic bottles behavior and sex and food-can linings ----------------------------------------------------Dibutyl Cosmetics Gene and hormone Phthalate shampoos, pills changes in rodents; (DBP) nail polish, genital abnormalities plastic toys in human infants ----------------------------------------------------Diethylhexy Polyvinylchloride Birth defects in Phthalate building products, mice; pre-term birth (DEHP) food packaging, in human infants; toys, medical early puberty in girls tubing ----------------------------------------------------Perchlorate Drinking water in Brain and behavior 35 states, fruits, changes in rats; vegetables, thyroid effects in breast milk people ----------------------------------------------------sources: Scientific articles; US Environmental Protection Agency With so much still unknown, regulators are proceeding on different tracks in different countries. Japan's government designates about 70 chemicals as potential "endocrine disruptors" — substances that may, at tiny doses, interfere with hormonal signals that regulate human organ development, metabolism and other functions. Japan has just completed a $135 million research push on endocrine disruptors, including setting up a national research center. The Japanese government also has banned certain phthalates in food handlers' gloves and containers, after detecting them in food. One manufacturer, Fujitsu Ltd., has pledged to phase out its use of most suspected endocrine disruptors over coming years. The European Union has banned some kinds of phthalates in cosmetics and toys, and it is considering a ban on nearly all phthalates in household goods and medical devices. The EU also is planning to require new safety tests for thousands of industrial chemicals, many of which already exist in people's bodies at trace levels. Industry, which would have to bear the cost of proving countless current products safe, is fighting the measures, calling them a massive unnecessary burden. In the U.S., there are divisions within the government. The White House plays down the issue, saying the low-dose hypothesis is unproved. But many federal scientists and regulators at the EPA and Health and Human Services Department are forging ahead with new methods for assessing possible low-dose dangers. Legislatures in two states, California and New York, are considering bills that would ban use of certain phthalates in toys, child-care products and cosmetics, while a California bill would restrict bisphenol A. Earliest Concerns One of the early scientists to focus on possible low-dose risks was biologist Theo Colborn of the World Wildlife Fund. Studying the decline of certain birds, mammals and fish in the upper Midwest, Dr. Colborn spotted some patterns: Species that struggled to survive in the industrialized Great Lakes thrived in inland areas that were less polluted. And some offspring in more-polluted regions had gender abnormalities, such as feminized sex organs in males. She theorized that trace amounts of chemicals in the environment were disrupting hormones. Dr. Colborn and colleagues popularized low-dose concerns in a series of conferences, articles and a best-selling 1996 book called "Our Stolen Future." That year the EPA asked an outside advisory panel to consider ways of screening industrial chemicals for hormonal effects, a process still incomplete. In 2000, a separate EPA-organized panel, after reviewing 49 studies, said some hormonally active chemicals affect animals at doses as low as the "background levels" to which the general human population is subject. The panel said the health implications weren't clear but urged the EPA to revisit its regulatory procedures to make sure such chemicals are tested in animals at appropriately small doses. The EPA hesitated. It responded in 2002 that "until there is an improved scientific understanding of the low-dose hypothesis, EPA believes that it would be premature to require routine testing of substances for low-dose effects." The Bush administration's regulatory czar, John Graham — administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs at the White House Office of Management and Budget — later publicly dismissed as unproven the idea that the hormonal system could be disrupted by multiple low-dose exposures to industrial chemicals. For the past two years, the administration has proposed funding cuts for EPA research on suspected endocrine disrupters, but Congress has kept the funding roughly level at about $10 million a year. Since the review panel met in 2000, scientists have published more than 100 peerreviewed articles reporting further low-dose effects in living animals and in human cells. These findings are generating some early insights in the thorny process of translating laboratory data into conclusions about human health. Less Is More One of the most provocative is that some hormonally active chemicals seem to have more effects at extremely low exposures than at higher ones. This challenges an axiom of toxicology stated by the Swiss chemist Paracelsus nearly 500 years ago: The dose makes the poison. Toxicologists traditionally derive risk by exposing rodents to chemicals to find the lowest dose that leads to tumors, birth defects or other readily observable effects. Regulators then divide the highest "no-observable-effect" dose by an "uncertainty factor" — anywhere from 10 to 1,000 — to set a maximum human exposure they can be confident is safe. But now researchers have found chemicals that have hormonal effects on lab animals and on human cells in much tinier amounts than their standard no-observable-effect levels. And with some of these chemicals, as the tiny doses given to animals are increased, the effects recede. Then, at much higher levels, broad systemic impacts appear, such as reduced body weight. An example is bisphenol A, or BPA, the ingredient in polycarbonate baby bottles and food-can linings. It evidently is widespread in the environment. In the U.S., the CDC has found traces of it in 95% of urine samples tested. In Japan, researchers have detected BPA in fetal amniotic fluid and the umbilical cords of newborns. Studying BPA in rats in 1988, the EPA concluded the lowest exposure with an "observed adverse effect" was 50 milligrams a day per kilogram of body weight (one kilogram = 2.2 pounds). Dividing 50 by an uncertainty factor of 1,000, the agency set a daily safe limit for humans of 0.05 milligrams of BPA per kilogram of body weight. Since then, however, academic scientists in several countries have done more than 90 studies that have found BPA effects on animals and human cell cultures from exposures well below this level. The EPA used a relatively crude measure of the chemical's effects: changes in rodents' body weights. The new studies looked at subtler, hormone-related effects. Some studies found changes in rodents' reproductive organs and brains at doses as low as 0.002 milligram per kilogram of body weight per day. That is just one-25,000th the dose that the EPA said was the lowest exposure having an observable adverse effect. Disrupting Hormones Seeking to explain this pattern, scientists cite the endocrine system's exquisite sensitivity. Animals and humans secrete infinitesimal amounts of various hormones, such as estrogen, that trigger responses when they occupy special receptors on the cells of various organs. BPA is among numerous chemicals that can mimic estrogen by occupying cells' estrogen receptors. When they do this at critical phases of development, the chemicals can trigger unnatural biological responses, such as brain and reproductive abnormalities. At higher doses, however, BPA and other endocrine disruptors — instead of triggering the unnatural responses — appear to overwhelm the receptors. That explains, scientists say, why some chemicals seem to have more potent hormonal effects at very low doses than at higher ones. Mr. Hentges of the American Plastics Council says studies show BPA is harmless at the tiny levels to which humans are exposed. In 2001 the plastics council agreed to pay Harvard's Center for Risk Analysis, part of the Harvard School of Public Health, $600,000 to review BPA studies. The 10 panelists found "no consistent affirmative evidence of low-dose BPA effects" on the basis of 19 studies that were selected by April 2002 for review. However, many more BPA studies kept coming out, and when the center published its report last fall, three of the 10 panelists declined to be listed as authors. "There are other papers published after the 'cut-off' date that the panel did not review that may have altered their conclusions," says one of the three, Paul Foster of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. A fourth, Claude Hughes of Quintiles Transnational Corp., a pharmaceutical consulting firm, signed but made the same point in a journal commentary criticizing the report and calling for a new EPA risk assessment. The Harvard risk center's executive director, George Gray, acknowledges that a "torrent of new papers on BPA" may have made it impossible for the panel to review everything by its deadline. The plastics council's Mr. Hentges says his group reviews all studies on BPA and believes none have changed the basic conclusion of the Harvard report. "We continue to believe that the weight of evidence indicates BPA poses no risk to human health," he says. Chemicals in Combination Environmental chemicals don't exist in isolation. People are exposed to many different ones in trace amounts. So scientists at the University of London checked a mixture. They tested the hormonal strength of a blend of 11 common chemicals that can mimic estrogen. Alone, each was very weak. But when scientists mixed low doses of all 11 in a solution with natural estrogen — thus simulating the chemical cocktail that's inside the human body today — they found the hormonal strength of natural estrogen was doubled. Such an effect inside the body could disrupt hormonal action. "In isolation, the contribution of individual [estrogen-like chemicals] at the concentrations found in wildlife and human tissues will always be small," wrote the scientists, led by Andreas Kortenkamp, who directs research on endocrine disruptors for the EU. But because such compounds are so widespread in the environment, the researchers concluded, the cumulative effect on the human endocrine system is "likely to be very large." To test chemicals, toxicologists traditionally dose animals with a single substance and then dissect them. But this method can't spot the subtle effects associated with today's multiple exposures to low-dose chemicals, says John Bucher, of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Now he and his boss, Christopher Portier, are revamping the federal government's National Toxicology Program, which sets standards for how chemicals are tested. Over about seven years, they hope to develop a series of lab tests that will ultimately screen some 100,000 industrial compounds, individually and in mixtures, for biochemical "markers" such as effects on specific genes. The chemicals then will be ranked by mechanism of action and suspected toxicity, and assigned priorities for further study. "It's taken us 25 years and $2 billion to study 900 chemicals," Dr. Portier says. "If this works, we can study 15,000 in a year." Page A1