Overview of the Policy and Regulatory Frameworks for

advertisement

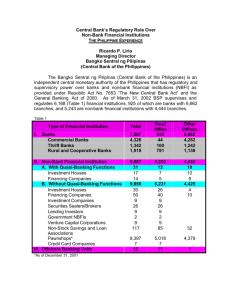

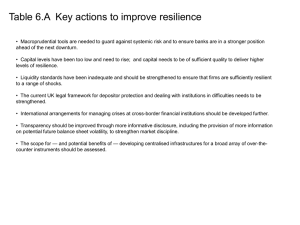

Overview of the Policy and Regulatory Frameworks for NBFIs Dr Jeffrey Carmichael Chairman, Carmichael Consulting Pty Ltd Former Chairman, Australian Prudential Regulation Authority Presentation delivered to: A Regional Seminar on Non-Bank Financial Institutions Development In African Countries December 9-11, 2003, Mauritius Sponsored by the World Bank 1 Overview of the Policy and Regulatory Frameworks for NBFIs 1. Introduction Non-bank financial institutions have an important role to play in economic and financial development. In general, NBFIs and development of the financial system go hand in hand. Without an effective non-bank financial sector, economic and financial broadening tend to be retarded. But, while NBFIs are a potential positive influence on the economy, they can also be a source of risk. The main way of controlling these risks is through regulation. The challenge for regulation is to strike the right balance between the risks and the positive contributions. On the one hand, too little (or misguided) regulation can lead to crises. On the other, overly intrusive (or inappropriate) regulation can negate the potential positive contribution of NBFIs to growth and development. Getting this balance right for NBFIs is made more difficult by the fact that many areas of non-bank regulation are still very embryonic. This morning I want to talk about the regulatory framework and trying to find that magic balance between efficiency and effectiveness. This is a framework that Michael Pomerleano and I have been working on for some years. It has evolved through 2 Global Workshops in Washington, a series of Regional Workshops such as this one, and a book. The regulatory framework has 3 main elements: Regulatory objectives (i.e. why we regulate and what we hope to achieve through regulation); Regulatory structure (i.e. the structure of agencies that carry the delegated regulatory responsibilities of the community); and Regulatory effectiveness, subcomponents: which can be broken into two a) Regulatory backing (which includes the political, legal and financial backing available to regulators to enable them to carry out their duties effectively); and b) Regulatory implementation (the instruments, tools and techniques used by regulatory agencies to implement regulatory oversight). I am going to talk about the first two of these topics, namely regulatory objectives and structure. Iqbal Rajahbalee will then take up the effectiveness element in his presentation on powers and enforcement. But before I get to objectives and structure I want to start with a brief review of the contributions and risks associated with NBFIs. 2 2. Contributions and Risks Associated with NBFIs Financial institutions, including banks and non-banks, provide some or all of the following core financial services: Some financial institutions provide payments services – by issuing claims that have the capacity to be used in settling transactions. Liquidity is the ease with which an asset’s full market value can be realized once a decision to sell has been made. Divisibility is the extent to which an asset can be traded in small denominations. Store of value is the extent to which an asset provides a reliable store of purchasing power over time – this is fundamental to satisfying the savings preferences of the community. Information is costly to access and process. Providing economies of scale in processing and assessing risks is an important role of financial institutions. Risk pooling is the extent to which an asset spreads the default risk of the underlying promises by pooling. These services are often provided in combinations. Banks provide an attractive bundle of most of the core financial services in their deposit product. The ability to write cheques on deposits means that banks offer payments services and liquidity equal to that of currency. Deposits also offer exceptionally high divisibility (at least to the same level as currency and in some cases even higher). The store of value service is that of a debt promise in that deposits promise repayment at (nominal) face value plus interest. Banks resolve the information conflict faced by borrowers and generally enjoy substantial economies of scale in processing and analyzing information. Finally, banks risk pool borrowers’ promises into a single promise by the intermediary itself. This begs the obvious question – if banks offer all of these services why do we need NBFIs? The answer to this question is intuitive rather than empirical. In principle, there is no reason why banks can’t provide all the main financial services needed by the community – indeed to an extent they do. The problem is that they are extremely inefficient in providing some services and even face conflicting incentives in providing all services. 3 NBFIs complement banks by providing services that are not well suited to bank provision; they fill the gaps in financial services that otherwise occur in bankdominated financial systems. Equally important, NBFIs provide competition for banks in the provision of financial services. But there is more to the case for NBFIs than just logic. There is a growing body of hard evidence to suggest that: The development of financial intermediaries contributes strongly to economic growth; and That contribution is increased where intermediation is provided through a balanced combination of NBFIs and banks – in particular, there is a strong correlation between the depth and activeness of non-banks and stock markets on the one hand, and economic development on the other. The contribution to growth and welfare can be significant – so what about the risks? There are two main sources of systemic risk that arise from NBFIs. The first is that NBFIs can be used as a means of circumventing the intent of regulations imposed on banks. This effect has been clearest where NBFIs have been either totally or largely unregulated and have thereby gained a competitive advantage in competing with regulated banks on their own territory. The fallout from this type of behaviour was very evident in the Asian crisis in the late 1990s. In Thailand, finance companies issued high-yielding borrowed offshore, then loaned the funds in local borrowers who could not meet banking standards – mid 1997, the Government was forced to close companies; Malaysia experienced similar problems with finance companies that had extended hire-purchase loans; In Korea, NBFIs grew very strongly in the pre-97 period precisely because they competed directly with banks, but with a regulatory advantage. This included merchant banks in the pre-97 period, which borrowed offshore and helped leverage the Chaebol. The problem re-emerged in a different guise between 1997 and 1999 when poorly regulated Investment Trust Companies took over as the primary source of corporate finance. promissory notes and currency to high-risk when the crisis hit, in 69 insolvent finance The message here is fairly obvious – but important enough to warrant restatement. 4 Competition between NBFIs and banks in providing financial services is healthy. But competition based on lax regulation is unhealthy - and can have disastrous consequences that may affect economic growth and financial stability for years. The second major risk with NBFIs arises from their association with banks through conglomerates. This factor was also a contributor to the Asian crisis in the late 1990s, most particularly in Korea and Indonesia. But the problem is by no means confined to emerging markets. Australia has lost only two banks through outright failure in the past century. But both failed because of high-risk activities carried out through their unregulated and very large subsidiaries. It is my perception that conglomerates are not a major issue for many African countries. Mauritius may be one of the few exceptions here and also South Africa. But for most countries in the region, financial institutions appear to be largely stand-alone specialized institutions. The risks in this region are a little different. Here the risks are twofold. In some countries, the biggest risk with NBFIs is simply their size. Swaziland is a good example. In Swaziland the bank domination of the financial system is one of the lowest in the world. Not only are NBFIs large, as a group they are growing much more quickly than banks. The second source of risk in the region is the concentration of some NBFI sectors. When NBFIs are large relative to banks, and industry concentration is high, the NBFI sector carries a much higher than usual risk to systemic stability. Countries with this configuration should place an extremely high priority on establishing a sound regulatory framework for NBFIs. The third source of risk I should mention arises from the large scale of a small number of companies in some African countries. When one or two companies dominate the corporate sector it is very hard for financial institutions such as local banks and insurance companies to meet their financial needs while at the same time diversifying their own risks. These risks are compounded by the relative underdevelopment of non-bank regulation in many African countries. That brings me to my next topic – namely regulatory objectives. 3. Objectives of Regulation It is very easy to lose sight of why we regulate and to assume that tougher regulation is necessarily better. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth. Regulation should be appropriate to the situation. To determine the best form and intensity of regulation we need first to step back and ask exactly why we regulate and what we hope to achieve through regulation. In line with academic thinking, the primary rationale for regulation has to be some form of market failure. In the absence of market failure, regulation can only 5 reduce efficiency. In broad terms, markets fail to produce efficient, competitive outcomes for one or more of the following reasons: • Anti-competitive behaviour; • Market misconduct; • Information asymmetry; and • Systemic instability. What is interesting about these four sources of market failure is that, by and large, they require different regulatory tools to counteract the market failure. Anti-competitive Behavior Governments generally foster competition in the financial sector because of the benefits it brings to the economy overall. These benefits include improved access to capital for business, cheaper credit and housing loans to consumers, a better match between the financing needs of deficit and surplus units, cheaper transactions, and a greater ability to manage risks. Market forces are the main determinant of competition. The role of competition regulation is to ensure that these forces operate effectively and are not circumvented by market participants. The key measures used in competition policy are: Rules designed to deal with the structure of industries (merger or antitrust laws); Rules designed to prevent anti-competitive behavior (e.g., collusion); and Rules designed to ensure that markets remain contestable (by ensuring that there is relatively free entry and exit). Market Misconduct Financial markets cannot operate efficiently and effectively unless participants act with integrity and unless there is adequate information on which to base informed judgments. The two areas of misconduct most common in financial markets are: Unfair or fraudulent conduct by market participants; and Inadequate disclosure of information. Regulation to address these sources of market failure is usually referred to as market conduct regulation. This form of regulation seeks to protect market 6 participants and, through this, to promote confidence in the efficiency and fairness of markets. Market conduct regulation typically focuses on: Disclosure of information; Conduct of business rules; Entry restrictions through licensing; Governance and fiduciary responsibilities; and Some minimal financial strength conditions (capital requirements where the nature of the financial promises involved warrant it). Asymmetric Information The third source of market failure, information asymmetry, arises where products or services are sufficiently complex that disclosure, by itself, is insufficient to enable consumers to make informed choices. This arises where buyers and sellers of particular products or services will never be equally well informed, regardless of how much information is disclosed. The issue is one of complexity of the product and of the institution offering it. This problem is common in areas such as drugs and aviation and it is particularly relevant in the area of financial services. The form of regulation involved in counteracting asymmetric information problems is usually referred to as ‘prudential regulation’. Prudential regulation overcomes the asymmetric information market failure in part by substituting the judgment of a regulator for that of the regulated financial institutions and their customers. Prudential regulatory measures include: Entry requirements; Capital requirements; Liquidity requirements; Governance requirements; and Customer support schemes (such as deposit insurance and industry guarantee funds). Systemic Instability The fourth, and final, source of market failure is systemic instability. It is a fundamental characteristic of parts of the financial system that they operate 7 efficiently only to the extent that market participants have confidence in their ability to perform the roles for which they were designed. Systemic instability arises where failure of one institution to honor its promises can lead to a general panic as individuals fear that similar promises made by other institutions may also be dishonored. A crisis occurs when contagion of this type leads to the distress or failure of otherwise sound institutions. Perhaps the greatest vulnerability to systemic crisis is in the payments system. The primary defense against systemic instability is the maintenance of a sustainable macroeconomic environment, with reasonable price stability in both product and asset markets. This responsibility falls directly to Government in its formulation of monetary and fiscal policy. Systemic stability is also supported by having a prudentially sound system of financial institutions. Beyond these general macroeconomic and prudential measures, the additional regulatory tools most appropriate to resolving this type of market failure are the lender of last resort facility and direct regulation of the payments system. Based on the market failure analysis it seems reasonable to assume that the primary objectives of financial regulation should be to correct those failures in order to ensure that: Financial markets are competitive (competition regulation); Financial markets are efficient and fair (conduct regulation); Institutions making complex financial promises to retail consumers are financially sound (prudential regulation); and The financial system remains stable overall. These are admirable objectives. However, we should be very conscious of what regulators can and can’t deliver. No market conduct regulator can guarantee that market abuses will not occur. More to the point, no prudential regulator can promise a complete absence of failures. In particular, no prudential regulator has the capacity to eliminate fraud. While no regulator can guarantee that it will achieve its objectives completely, the effectiveness of both types of regulation can be raised through improvements in four main areas. The first is the establishment of a structure of regulatory agencies that minimizes regulatory gaps and ensures an efficient regulatory coverage of the industry. The second is the development of stronger regulatory laws that provide the regulator with a comprehensive set of powers to meet its objectives. 8 The third is the development by the regulatory agency itself of stronger policies – through regulations, prudential standards, policy statements, and guidance notes. The fourth is improvements in the practices and procedures of the regulator that guide the implementation of the policies. It is in this area that most regulatory failures occur - it is not all that difficult to develop a set of regulations that stand up to the broad international requirements of the Basel Committee, IAIS, IOSCO and so on. It is a much more difficult challenge to implement and enforce those policies effectively. As mentioned earlier, Iqbal will address the issue of powers, policies and enforcement. That leaves me with the topic of regulatory structure. 4. Regulatory Structure The obvious motivation for interest in this topic is the number of countries that have adopted some form of integrated regulatory structure in recent times. While integrated regulation is still in the minority, it is rapidly growing in popularity. According to a recent World Bank study1, at the end of 2002, there were 6 main regulatory structures found throughout the world. For convenience, I will label the various options as the ‘separate regulators’ model, the ‘Mexican’ model, the ‘South African’ model, the ‘Canadian’ model, the ‘UK’ model, and the ‘Singaporean’ model. This classification should not be taken to imply that these particular countries were necessarily the pioneers of their particular structure. The classification is purely for convenience. The models can be summarised as follows: The Separate Regulators Model According to the World Bank study there were around 31 countries in the world that maintained separate regulators for each group of institutions. The Mexican Model – combining banking and securities regulation. According to the World Bank study there were 9 countries that combined banking and securities regulation. The South African Model – combining securities and insurance regulation. According to the World Bank study there were 3 countries that combined securities and insurance regulation. The Canadian Model – combining all or most prudential regulation (banking, insurance and, in some cases, pensions) in an institution separate from the central bank. 1 José de Luna Martínez and Thomas A. Rose (2003) International Survey of Integrated Supervision. 9 According to the World Bank study there were 13 countries that combined at least banking and insurance regulation in an institution separate from the central bank. The UK Model – combining all banking and non-banking regulation in an institution separate from the central bank. According to the World Bank study there were 10 countries that unified all regulation in an agency separate from the central bank. The Singaporean Model – combining all banking and non-banking regulation within the central bank. According to the World Bank study there were 3 countries that unified all financial regulation within the central bank. Before discussing the relative strengths and weaknesses of these models let me make a clear statement: There is no single best model that suits every country or even any one country for all time. The optimal regulatory structure at any point in time is always a compromise between conflicting pressures and is very influenced by the structure of the finance industry, the stage of development, the size of the economy and so. So what then are their relative strengths and weaknesses? 5. Comments on the Structural Models Separate Regulators Model Pros: Is easiest to implement – especially if that is where you are starting from. Best facilitates tailoring of regulation/supervision to the individual industries. Cons: Lack of scale in any one regulatory agency. No chance to extract synergies from different types of regulation. High cost due to duplication of infrastructures. Does not deal easily with financial conglomerates. Potential for regulatory arbitrage and even for some to escape regulation. Potential for regulatory capture of small agencies by large industries. 10 Mexican Model – Banking and Securities Pros: Combined regulator has greater scale, therefore more resource efficient that independent regulators. Banks often acts as securities dealers, therefore provides greater consistency. Less resource inefficient than separate regulators model. Cons: Not many obvious synergies between banking (prudential) and securities regulation (largely conduct). Can get a clash of cultures. Possible loss of focus in dealing with both prudential and conduct regulation. If the agency is the central bank there is a risk that either banking supervision may become distracted or that securities regulation will be neglected because it is outside the central bank’s expertise. If the agency is not the central bank there may be some loss of credibility and resources for bank supervision by removing it from the central bank. Can still have problems regulating conglomerates that cut across prudentially regulated institutions. By leaving other prudentially regulated institutions outside the integrated agency, there is still the potential for regulatory arbitrage. Still some duplication of infrastructures. Depending on the size of the remaining prudential regulators, there may still be potential for regulatory capture of small agencies by large industries. South African Model – all non-banks together Pros: Some scale economies and efficiency of resource use. Some synergies from bringing all non-bank regulators together. Leaves the central bank free to concentrate on banking regulation and monetary policy. Doesn’t impair banking supervision by removing it from the central bank. 11 Cons: Synergies are still fairly limited between the two types of regulation, although there may be significant gains within the non-bank prudential field. May still have some cultural clashes. Possible loss of focus in dealing with both prudential and conduct regulation. Still has some duplication of infrastructure. Need to ensure that the non-bank regulator has sufficient resources. May still face some problems supervising conglomerates. Canadian Model – all prudential regulation together Pros: Significant scale economies and efficiency of resource use. Potentially significant synergies from bringing all prudential regulators together. Less scope for regulatory arbitrage. Leaves the central bank free to concentrate on monetary policy. When carried to its extreme (as it is in Australia), it aligns the regulatory agencies with the sources of market failure - which has a neatness that I have to say is probably more impressive in the abstract than it is in practice. Cons: Still has some duplication of infrastructure. May be some loss of credibility and resources for bank supervision by removing it from the central bank May still face some problems supervising conglomerates if the straddle prudential and conduct areas. Need to ensure that regulation does not become “one-size fits all”. UK Model – Super regulator outside the central bank Pros: Very cost effective in terms of scale. 12 Maximizes synergies in risk management and prudential supervision. Should eliminate regulatory arbitrage. Deals best with conglomerates. Does not distract the central bank from monetary policy. Cons: Potential clash of cultures. Possible loss of focus in dealing with both prudential and conduct regulation. May be some loss of credibility and resources for bank supervision by removing it from the central bank Potential for reputational contagion if any sector strikes problems Regulator may become “too” powerful. Need to ensure that regulation does not become “one-size fits all”. The Singaporean Model Pros: Maximum cost effectiveness in terms of infrastructure and economies of scale. Maximizes synergies in supervision. Should eliminate regulatory arbitrage. Should deal well with conglomerates Avoids any loss of credibility or resources for banking supervision. Central bank regulates all systemically significant institutions, thereby giving it total responsibility for systemic stability regulation. Cons: Extremely powerful agency – needs strong accountability to offset. Multiple objectives could lead to distraction from monetary policy and supervision. More cultures to clash. Takes central bank well away from traditional core competencies. 13 7. Again the risk that regulation may become “one size fits all”. Weighing the Issues As should be clear from the discussion above, no single option is without both costs and benefits. Choosing among these options requires careful weighing of the relative importance of the costs and benefits. It also requires careful consideration of how the costs of preferred options might be mitigated either by innovative design or by finding ways around roadblocks that may otherwise appear impenetrable. These will vary from country to country and from situation to situation. It is relevant, nevertheless, to observe that those countries that have gone down the road of integrating their regulatory agencies in recent years have typically done it for one or more of the following reasons: To eliminate or reduce regulatory arbitrage; To better cope with the regulation of conglomerates; or To make more efficient use of scarce regulatory resources. My time is up, so let me leave you with three thoughts on structural reform. Suppose you analyse your own country’s situation and decide that it is time for some structural reform: First, to repeat a point I made earlier, don’t expect structural change to solve regulatory failures; Second, that said, structural reform does provide a rare opportunity to get some much needed reforms in regulatory powers. My suggestion is that, if you go down the structural reform route, take your time to make sure that you get all the associated reforms that you need. Politicians will usually only give you one round of legislative reform at a time – don’t waste it; Third, beware the vested interests. It is all very well to decide that there is merit in amalgamating this regulatory agency with that, or moving regulatory responsibilities from one agency to another. Reality sets in when the master turf protectors realize that they are losing resources or powers. What may start as a co-operative venture can quickly degenerate into open range warfare to stop the reforms. 14