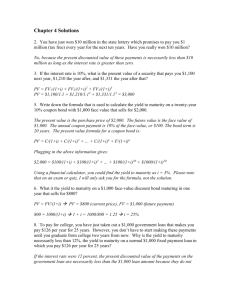

Municipal Securities - Florida International University

advertisement

CHAPTER 8 MUNICIPAL SECURITIES CHAPTER SUMMARY Municipal securities are issued by state and local governments and by governmental entities such as “authorities” or special districts. There are both tax-exempt and taxable municipal bonds. Most municipal bonds outstanding are tax-exempt, which means that interest on municipal bonds is exempt from federal income taxation, and it may or may not be taxable at the state and local levels. Proceeds from the sale of short-term notes permit the issuing municipality to cover seasonal and temporary imbalances between outlays for expenditures and inflows from taxes. Municipalities issue long-term bonds as the principal means for financing both long-term capital projects such as schools, bridges, roads, and airports and long-term budget deficits that arise from current operations. TYPES AND FEATURES OF MUNICIPAL SECURITIES There are basically two different types of municipal bond security structures: tax-backed bonds and revenue bonds. There are also securities that share characteristics of both tax-backed and revenue bonds. Tax-Backed Debt Tax-backed debt obligations are instruments issued by states, counties, special districts, cities, towns, and school districts that are secured by some form of tax revenue. Tax-backed debt includes general obligation debt, appropriation-backed obligations, and debt obligations supported by public credit enhancement programs. The broadest type of tax-backed debt is general obligation debt. An unlimited tax general obligation debt is the stronger form of general obligation pledge because it is secured by the issuer’s unlimited taxing power. A limited tax general obligation debt is a limited tax pledge because for such debt there is a statutory limit on tax rates that the issuer may levy to service the debt. Agencies or authorities of several states have issued bonds that carry a potential state liability for making up shortfalls in the issuing entity’s obligation. However, the state’s pledge is not binding. Debt obligations with this nonbinding pledge of tax revenue are called moral obligation bonds. Revenue Bonds The second basic type of security structure is found in a revenue bond. Such bonds are issued for either project or enterprise financings in which the bond issuers pledge to the bondholders the revenues generated by the operating projects financed. For a revenue bond, the revenue of the enterprise is pledged to service the debt of the issue. The details of how revenue received by the 165 enterprise will be disbursed are set forth in the trust indenture. There are various restrictive covenants included in the trust indenture for a revenue bond to protect the bondholders. A rate, or user charge, covenant dictates how charges will be set on the product or service sold by the enterprise. An additional bonds’ covenant indicates whether additional bonds with the same lien may be issued. Other covenants specify that the facility may not be sold, the amount of insurance to be maintained, requirements for recordkeeping and for the auditing of the enterprise’s financial statements by an independent accounting firm, and requirements for maintaining the facilities in good order. Hybrid and Special Bond Securities Some municipal bonds that have the basic characteristics of general obligation bonds and revenue bonds have more issue-specific structures as well. Some examples are insured bonds, bank-backed municipal bonds, refunded bonds, structured/asset-backed securities, and “troubled city” bailout bonds. Insured bonds, in addition to being secured by the issuer’s revenue, are also backed by insurance policies written by commercial insurance companies. Because municipal bond insurance reduces credit risk for the investor, the marketability of certain municipal bonds can be greatly expanded. There are two major groups of municipal bond insurers. The first includes the monoline companies that are primarily in the business of insuring municipal bonds. Almost all of the companies that are now insuring municipal bonds can be characterized as monoline in structure. The second group of municipal bond insurers includes the multiline property and casualty companies that usually have a wide base of business, including insurance for fires, collisions, hurricanes, and health problems. Since the 1980s, municipal obligations have been increasingly supported by various types of credit facilities provided by commercial banks. There are three basic types of bank support: letter of credit, irrevocable line of credit, and revolving line of credit. A letter-of-credit agreement is the strongest type of support available from a commercial bank. Under this arrangement, the bank is required to advance funds to the trustee if a default has occurred. An irrevocable line of credit is not a guarantee of the bond issue, although it does provide a level of security. A revolving line of credit is a liquidity-type credit facility that provides a source of liquidity for payment of maturing debt in the event that no other funds of the issuer are currently available. Although originally issued as either revenue or general obligation bonds, municipals are sometimes refunded. A refunding usually occurs when the original bonds are escrowed or collateralized by direct obligations guaranteed by the U.S. government. The escrow fund for a refunded municipal bond can be structured so that the refunded bonds are to be called at the first possible call date or a subsequent call date established in the original bond indenture. Such bonds are known as prerefunded municipal bonds. Although refunded bonds are usually retired at their first or subsequent call date, some are structured to match the debt obligation to the retirement date. Such bonds are known as escrowed-to-maturity bonds. 166 There are three reasons why a municipal issuer may refund an issue by creating an escrow fund. First, many refunded issues were originally issued as revenue bonds. Second, some issues are refunded in order to alter the maturity schedule of the obligation. Third, when interest rates decline after a municipal security is issued, there is a tax arbitrage opportunity available to the issuer by paying existing bondholders a lower interest rate and using the proceeds to create a portfolio of U.S. government securities paying a higher interest rate. Redemption Features Municipal bonds are issued with one of two debt retirement structures, or a combination. Either a bond has a serial maturity structure or it has a term maturity structure. A serial maturity structure requires a portion of the debt obligation to be retired each year. A term maturity structure provides for the debt obligation to be repaid on a final date. Special Investment Features The municipal market has securities with various features. These are zero-coupon bonds, floating-rate bonds, and putable bonds in the municipal bond market. For this market, there are two types of zero-coupon bonds. One type is issued at a very deep discount and matures at par. The difference between the par value and the purchase price represents a predetermined compound yield. These zero-coupon bonds are similar to those issued in the taxable bond market for Treasuries and corporates. The second type is called a municipal multiplier. This is a bond issued at par that has interest payments. The interest payments are not distributed to the holder of the bond until maturity, but the issuer agrees to reinvest the undistributed interest payments at the bond’s yield to maturity when it was issued. MUNICIPAL MONEY MARKET PRODUCTS Tax-exempt money market products include notes, commercial paper, variable-rate demand obligations, and a hybrid of the last two products. Municipal Notes Municipal notes include tax anticipation notes (TANs), revenue anticipation notes (RANs), grant anticipation notes (GANs), and bond anticipation notes (BANs). These are temporary borrowings by states, local governments, and special jurisdictions. Usually, notes are issued for a period of 12 months, although it is not uncommon for notes to be issued for periods as short as three months and for as long as three years. TANs and RANs (also known as TRANs) are issued in anticipation of the collection of taxes or other expected revenues. These are borrowings to even out irregular flows into the treasuries of the issuing entity. BANs are issued in anticipation of the sale of long-term bonds. Tax-Exempt Commercial Paper As with commercial paper issued by corporations, tax-exempt commercial paper is used by 167 municipalities to raise funds on a short-term basis ranging from one to 270 days. The dealer sets interest rates for various maturity dates and the investor then selects the desired date. Variable-Rate Demand Obligations Variable-rate demand obligations (VRDOs) are floating-rate obligations that have a nominal long-term maturity but have a coupon rate that is reset either daily or every seven days. The investor has an option to put the issue back to the trustee at any time with seven days’ notice. The put price is par plus accrued interest. Commercial Paper/VRDO Hybrid The commercial paper/VRDO hybrid is customized to meet the cash flow needs of an investor. As with tax-exempt commercial paper, there is flexibility in structuring the maturity, because the remarketing agent establishes interest rates for a range of maturities. Although the instrument may have a long nominal maturity, there is a put provision, as with a VRDO. MUNICIPAL DERIVATIVE SECURITIES In recent years, a number of municipal products have been created from the basic fixed-rate municipal bond. This has been done by splitting up cash flows of newly issued bonds as well as bonds existing in the secondary markets. These products have been created by dividing the coupon interest payments and principal payments into two or more bond classes, or tranches. The name derivative securities has been attributed to these bond classes because they derive their value from the underlying fixed-rate municipal bond. Floaters / Inverse Floaters A common type of derivative security is one in which two classes of securities, a floating-rate security and an inverse-floating-rate bond, are created from a fixed-rate bond. The coupon rate on the floating-rate security is reset based on the results of a Dutch auction. Inverse floaters can be created in one of three ways. First, a municipal dealer can buy in the secondary market a fixed-rate municipal bond and place it in a trust. The trust then issues a floater and an inverse floater. The second method is similar to the first except that the municipal dealer uses a newly issued municipal bond to create a floater and an inverse floater. The third method is to create an inverse floater without the need to create a floater. This is done using the municipal swaps market. Strips and Partial Strips Municipal strip obligations are created when a municipal bond’s cash flows are used to back zero-coupon instruments. The maturity value of each zero-coupon bond represents a cash flow on the underlying security. Partial strips have also been created from cash bonds, which are zero-coupon instruments to a 168 particular date, such as a call date, and then converted into coupon paying instruments. These are called convertibles or step-up bonds. Other products can be created by allocating the interest payments and principal of a fixed-coupon-rate municipal bond to more than two bond classes. CREDIT RISK Although municipal bonds at one time were considered second in safety only to U.S. Treasury securities, today there are new concerns about the credit risks of municipal securities. The first concern came out of the New York City billion-dollar financial crisis in 1975. The second reason for concern about municipal securities credit risk is the proliferation in this market of innovative financing techniques to secure new bond issues. What distinguishes these newer bonds from the more traditional general obligation and revenue bonds is that there is no history of court decisions or other case law that firmly establishes the rights of the bondholders and the obligations of the issuers. As with corporate bonds, some institutional investors in the municipal bond market rely on their own in-house municipal credit analysts for determining the credit worthiness of a municipal issue; other investors rely on the nationally recognized rating companies. The two leading rating companies are Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s, and the assigned rating system is essentially the same as that used for corporate bonds. Although there are numerous security structures for revenue bonds, the underlying principle in rating is whether the project being financed will generate sufficient cash flow to satisfy the obligations due bondholders. RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH INVESTING IN MUNICIPAL SECURITIES The investor in municipal securities is exposed to the same risks affecting corporate bonds plus an additional one that may be labeled tax risk. There are two types of tax risk to which taxexempt municipal securities buyers are exposed. The first is the risk that the federal income tax rate will be reduced. The second type of tax risk is that a municipal bond issued as a tax-exempt issue may eventually be declared to be taxable by the Internal Revenue Service. YIELDS ON MUNICIPAL BONDS A common yield measure used to compare the yield on a tax-exempt municipal bond with a comparable taxable bond is the equivalent taxable yield. The equivalent taxable yield is computed as follows: equivalent taxable yield = tax-exempt yield . ( 1 marginal tax rate ) Yield Spreads Because of the tax-exempt feature of municipal bonds, the yield on municipal bonds is less than that on Treasuries with the same maturity. The yield on municipal bonds is compared to the yield on Treasury bonds with the same maturity by computing the following ratio: 169 yield ratio = yield on municipal bond . yield on same maturity Treasury bond Yield spreads within the municipal bond market are attributable to differences between credit ratings (i.e., quality spreads), sectors within markets (intramarket spreads), and differences between maturities (maturity spreads). MUNICIPAL BOND MARKET Primary Market A substantial number of municipal obligations are brought to market each week. A state or local government can market its new issue by offering bonds publicly to the investing community or by placing them privately with a small group of investors. When a public offering is selected, the issue usually is underwritten by investment bankers and/or municipal bond departments of commercial banks. Most states mandate that general obligation issues be marketed through competitive bidding, but generally this is not required for revenue bonds. An official statement describing the issue and the issuer is prepared for new offerings. Municipal bonds have legal opinions that are summarized in the official statement. Secondary Market Municipal bonds are traded in the over-the-counter market supported by municipal bond dealers across the country. Markets are maintained on smaller issuers (referred to as local general credits) by regional brokerage firms, local banks, and by some of the larger Wall Street firms. Larger issuers (referred to as general names) are supported by the larger brokerage firms and banks, many of whom have investment banking relationships with these issuers. The convention for both corporate and Treasury bonds is to quote prices as a percentage of par value with 100 equal to par. Municipal bonds, however, generally are traded and quoted in terms of yield (yield to maturity or yield to call). The price of the bond in this case is called a basis price. The exception is certain long-maturity revenue bonds. A bond traded and quoted in dollar prices (actually, as a percentage of par value) is called a dollar bond. THE TAXABLE MUNICIPAL BOND MARKET Taxable municipal bonds are bonds whose interest is taxed at the federal income tax level. Because there is no tax advantage, an issuer must offer a higher yield than for another taxexempt municipal bond. Why would a municipality want to issue a taxable municipal bond and thereby have to pay a higher yield than if it issued a tax-exempt municipal bond? There are three reasons for this. First, some activities do not benefit the public at large and municipalities have to finance these restricted activities in the taxable bond market. Second, the U.S. income tax code imposes restrictions on arbitrage opportunities that a municipality can realize from its financing activities. Third, municipalities do not view their potential investor base as solely U.S. investors. When bonds are issued outside of the United States, the investor does not benefit from the taxexempt feature. 170 The most common types of activities for taxable municipal bonds used for financing are (i) local sports facilities, (ii) investor-led housing projects, (iii) advanced refunding of issues that are not permitted to be refunded because the tax law prohibits such activity, and (iv) underfunded pension plan obligations of the municipality. 171 ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS FOR CHAPTER 8 (Questions are in bold print followed by answers.) 1. Answer the following questions. (a) Explain why you agree or disagree with the following statement: “All municipal bonds are exempt from federal income taxes.” One would disagree with the statement: “All municipal bonds are exempt from federal income taxes.” The argument and clarification are given below. Municipal securities are issued by state and local governments and by governmental entities such as “authorities” or special districts. There are both tax-exempt and taxable municipal bonds. “Tax-exempt” means that interest on municipal bonds is exempt from federal income taxation, and it may or may not be taxable at the state and local levels. Most municipal bonds outstanding are tax-exempt. Taxable municipal bonds are bonds whose interests are taxed at the federal income tax level. Because there is no tax advantage, an issuer must offer a higher yield than for another taxexempt municipal bond. The yield must be higher than the yield on U.S. government bonds because an investor faces credit risk by investing in a taxable municipal bond. The investors in taxable municipal bonds are investors who view them as alternatives to corporate bonds. (b) Explain why you agree or disagree with the following statement: “All municipal bonds are exempt from state and local taxes.” One would disagree with the statement that all municipal bonds are exempt from state and local taxes. “Tax-exempt” means that interest on municipal bonds is exempt from federal income taxation, and it may or may not be taxable at the state and local levels. Thus, not all municipal bonds are exempt from state and local taxes. 2. If Congress changes the tax law so as to increase marginal tax rates, what will happen to the price of municipal bonds? An increase in the maximum marginal tax rate for individuals will increase the attractiveness of municipal securities. This was seen with the Tax Act of 1990 which raised the maximum marginal tax rate to 33%. Ceteris paribus, an increase in tax rates will have a positive effect on the price of municipal securities as demand will increase. An increase in price is needed to restore the desired returns. On the other hand, a decrease in the maximum marginal tax rate for individuals will decrease the attractiveness of municipal securities. This was seen with the Tax Reform Act of 1986 where the maximum marginal tax rate for individuals was reduced from 50% to 28%. Ceteris paribus, a decrease in tax rates will have a negative effect on the price of municipal bonds as demand will decrease. The effect of a lower tax rate was once again seen in 1995 with congressional 172 proposals regarding the introduction of a flat tax when tax-exempt municipal bonds began trading at lower prices. The higher the marginal tax rate, the greater the value of the tax exemption features. As the marginal tax rate declines, the price of a tax-exempt municipal security also declines. 3. What is the difference between a general obligation bond and a revenue bond? The two basic security structures are tax-backed debt and revenue bonds. The former are secured by the issuer’s general taxing power. Revenue bonds are used to finance specific projects and are dependent on revenues from those projects to satisfy the obligations. Thus, the difference between general obligation bonds and revenue bonds involves how the bonds are secured. More details are supplied below. There are basically two different types of municipal bond security structures: tax-backed bonds and revenue bonds. Tax-backed debt obligations are instruments issued by states, counties, special districts, cities, towns, and school districts that are secured by some form of tax revenue. Tax-backed debt includes general obligation debt, appropriation-backed obligations, and debt obligations supported by public credit enhancement programs. The broadest type of tax-backed debt is general obligation debt. There are two types of general obligation pledges: unlimited and limited. An unlimited tax general obligation debt is the stronger form of general obligation pledge because it is secured by the issuer’s unlimited taxing power. The tax revenue sources include corporate and individual income taxes, sales taxes, and property taxes. Unlimited tax general obligation debt is said to be secured by the full faith and credit of the issuer. The second basic type of security structure is found in a revenue bond. Such bonds are issued for either project or enterprise financings in which the bond issuers pledge to the bondholders the revenues generated by the operating projects financed. For a revenue bond, the revenue of the enterprise is pledged to service the debt of the issue. There are various restrictive covenants included in the trust indenture for a revenue bond to protect the bondholders. A rate, or user charge, covenant dictates how charges will be set on the product or service sold by the enterprise. 4. Which type of municipal bond would an investor analyze using an approach similar to that for analyzing a corporate bond? Investors use a similar approach to analyze both municipal bonds and corporate bonds. As with corporate bonds, some institutional investors in the municipal bond market rely on their own inhouse municipal credit analysts for determining the credit worthiness of a municipal issue; other investors rely on the nationally recognized rating companies. The two leading rating companies are Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s, and the assigned rating system is essentially the same as that used for corporate bonds. More details on the actual procedure are given below. In evaluating general obligation bonds, the commercial rating companies assess information in four basic categories. The first category includes information on the issuer’s debt structure to determine the overall debt burden. The second category relates to the issuer’s ability and political 173 discipline to maintain sound budgetary policy. The focus of attention here usually is on the issuer’s general operating funds and whether it has maintained at least balanced budgets over three to five years. The third category involves determining the specific local taxes and intergovernmental revenues available to the issuer as well as obtaining historical information both on tax collection rates, which are important when looking at property tax levies, and on the dependence of local budgets on specific revenue sources. The fourth and last category of information necessary to the credit analysis is an assessment of the issuer’s overall socioeconomic environment. The determinations that have to be made here include trends of local employment distribution and composition, population growth, real estate property valuation, and personal income, among other economic factors. 5. In a revenue bond, which fund has priority when funds are disbursed from the reserve fund, the operation and maintenance fund, or the debt service reserve fund? For a revenue bond, the revenue of the enterprise is pledged to service the debt of the issue. The details of how revenue received by the enterprise will be disbursed are set forth in the trust indenture. Typically, the flow of funds for a revenue bond is as follows. First, all revenues from the enterprise are put into a revenue fund. It is from the revenue fund that disbursements for expenses are made to the following funds with priority given to those listed first: operation and maintenance fund, sinking fund, debt service reserve fund, renewal and replacement fund, reserve maintenance fund, and surplus fund. Thus, the operation and maintenance fund has priority over the debt service reserve fund. More details are supplied below. Operations of the enterprise have priority over the servicing of the issue’s debt, and cash needed to operate the enterprise is deposited from the revenue fund into the operation and maintenance fund. The pledge of revenue to the bondholders is a net revenue pledge, net meaning after operation expenses, so cash required to service the debt is deposited next in the sinking fund. Disbursements are then made to bondholders as specified in the trust indenture. Any remaining cash is then distributed to the reserve funds. The purpose of the debt service reserve fund is to accumulate cash to cover any shortfall of future revenue to service the issue’s debt. The specific amount that must be deposited is stated in the trust indenture. The function of the renewal and replacement fund is to accumulate cash for regularly scheduled major repairs and equipment replacement. The function of the reserve maintenance fund is to accumulate cash for extraordinary maintenance or replacement costs that might arise. Finally, if any cash remains after disbursement for operations, debt servicing, and reserves, it is deposited in the surplus fund. The issuer can use the cash in this fund in any way it deems appropriate. 6. In a revenue bond, what is a catastrophe call provision? In revenue bonds there is a catastrophe call provision that requires the issuer to call the entire issue if the facility is destroyed. More information on the retirement structure of municipal bonds including call provisions are given below. Municipal bonds are issued with one of two debt retirement structures, or a combination. Either a bond has a serial maturity structure or it has a term maturity structure. A serial maturity structure requires a portion of the debt obligation to be retired each year. A term maturity structure 174 provides for the debt obligation to be repaid on a final date. Usually, term bonds have maturities ranging from 20 to 40 years and retirement schedules (sinking fund provisions) that begin 5 to 10 years before the final term maturity. Municipal bonds may be called prior to the stated maturity date, either according to a mandatory sinking fund or at the option of the issuer. In revenue bonds there is a catastrophe call provision that requires the issuer to call the entire issue if the facility is destroyed. 7. What is the tax risk associated with investing in a municipal bond? The investor in municipal securities is exposed to the same risks affecting corporate bonds plus an additional one that may be labeled tax risk. There are two types of tax risk to which taxexempt municipal securities buyers are exposed. The first is the risk that the federal income tax rate will be reduced. The higher the marginal tax rate, the greater the value of the tax exemption feature. As the marginal tax rate declines, the price of a tax-exempt municipal security will decline. The second type of tax risk is that a municipal bond issued as a tax-exempt issue may eventually be declared to be taxable by the Internal Revenue Service. This may occur because many municipal revenue bonds have elaborate security structures that could be subject to future adverse congressional action and IRS interpretation. A loss of the tax exemption feature will cause the municipal bond to decline in value in order to provide a yield comparable to similar taxable bonds. 8. “An insured municipal bond is safer than an uninsured municipal bond.” Indicate whether you agree or disagree with this statement. Everything else being equal, an insured municipal bond is safer. However, generally speaking, municipal bonds that are insured are riskier than those not insured especially if they are of inferior quality. Thus, the insurance does not guarantee they are safer than an uninsured municipal bond. More details are supplied below. Insured bonds, in addition to being secured by the issuer’s revenue, are also backed by insurance policies written by commercial insurance companies. Insurance on a municipal bond is an agreement by an insurance company to pay the bondholder any bond principal and/or coupon interest that is due on a stated maturity date but that has not been paid by the bond issuer. When issued, this municipal bond insurance usually extends for the term of the bond issue, and it cannot be canceled by the insurance company. Because municipal bond insurance reduces credit risk for the investor, the marketability of certain municipal bonds can be greatly expanded. Municipal bonds that benefit most from the insurance would include lower quality bonds, bonds issued by smaller governmental units not widely known in the financial community, bonds that have a sound though complex and difficult-to-understand security structure, and bonds issued by infrequent local-government borrowers who do not have a general market following among investors. 175 9. In your view, would the typical AAA- or AA-rated municipal bond be insured? A major factor for an issuer to obtain bond insurance is that its credit worthiness without the insurance is substantially lower than what it would be with the insurance. This is more likely to be the case for a bond of lower quality. Thus, an AA-rated bond is more likely to profit from insurance than an AAA-rated. However, even for an AA-rated bond, it is still considered a quality grade and most investors would not be too concerned about default. Consequently, it is unlikely that the yield for an AA-rated municipal bond could be lowered enough by being insured to make up for the cost of insurance. In general, although insured municipal bonds sell at yields lower than they would without the insurance, they tend to have yields higher than other AAA-rated bonds. 10. Explain the different types of refunded bonds. Although originally issued as either revenue or general obligation bonds, municipals are sometimes refunded. Two types of refunded bonds are prerefunded and escrowed-to-maturity bonds. These types are described below. A refunding usually occurs when the original bonds are escrowed or collateralized by direct obligations guaranteed by the U.S. government. By this it is meant that a portfolio of securities guaranteed by the U.S. government is placed in trust. The portfolio of securities is assembled such that the cash flow from all the securities matches the obligations that the issuer must pay. When this portfolio of securities whose cash flow matches that of the municipality’s obligation is in place, the refunded bonds are no longer secured as either general obligation or revenue bonds. The bonds are now supported by the portfolio of securities held in an escrow fund. The escrow fund for a refunded municipal bond can be structured so that the refunded bonds are to be called at the first possible call date or a subsequent call date established in the original bond indenture. Such bonds are known as prerefunded municipal bonds. Although refunded bonds are usually retired at their first or subsequent call date, some are structured to match the debt obligation to the retirement date. Such bonds are known as escrowed-to-maturity bonds. 11. Give two reasons why an issuing municipality would want to refund an outstanding bond issue. There are three reasons why a municipal issuer may refund an issue by creating an escrow fund. First, many refunded issues were originally issued as revenue bonds. Included in revenue issues are restrictive-bond covenants. The municipality may wish to eliminate these restrictions. The creation of an escrow fund to pay the bondholders legally eliminates any restrictive-bond covenants. This is the motivation for the escrowed-to-maturity bonds. Second, some issues are refunded in order to alter the maturity schedule of the obligation. Third, when interest rates have declined after a municipal security has been issued, there is a tax arbitrage opportunity available to the issuer by paying existing bondholders a lower interest rate and using the proceeds to create a portfolio of U.S. government securities paying a higher interest rate. This is the motivation for the prerefunded bonds. 176 12. Answer the following questions. (a) What are the three basic types of bank support for a bank-backed municipal security? Since the 1980s, municipal obligations have been increasingly supported by various types of credit facilities provided by commercial banks. The support is in addition to the issuer’s cash flow revenues. There are three basic types of bank support: letter of credit, irrevocable line of credit, and revolving line of credit. (b) Which is the strongest type of support available from a commercial bank? A letter-of-credit agreement is the strongest type of support given by a commercial bank. Under this arrangement, the bank is required to advance funds to the trustee if there is a default. An irrevocable line of credit is not a guarantee of the bond issue, although it does provide security. A revolving line of credit is a liquidity-type credit facility that provides a source of liquidity for payment of maturing debt in the event that no other funds of the issuer are available. Because a bank can cancel a revolving line of credit without notice if the issuer fails to meet certain covenants, bond security depends entirely on the credit worthiness of the municipal issuer. 13. What are TAN, RAN, GAN, and BAN? Municipal notes include tax anticipation notes (TANs), revenue anticipation notes (RANs), grant anticipation notes (GANs), and bond anticipation notes (BANs). These are temporary borrowings by states, local governments, and special jurisdictions. Usually, notes are issued for a period of 12 months, although it is not uncommon for notes to be issued for periods as short as three months and for as long as three years. TANs and RANs (also known as TRANs) are issued in anticipation of the collection of taxes or other expected revenues. These are borrowings to even out irregular flows into the treasuries of the issuing entity. BANs are issued in anticipation of the sale of long-term bonds. 14. Why has there been a decline in the issuance of tax-exempt commercial paper? As with commercial paper issued by corporations, tax-exempt commercial paper is used by municipalities to raise funds on a short-term basis ranging from one to 270 days. The dealer sets interest rates for various maturity dates and the investor then selects the desired date. Provisions in the 1986 tax act have restricted the issuance of tax-exempt commercial paper. Specifically, the act limits the new issuance of municipal obligations that is tax exempt, and as a result, every maturity of a tax-exempt municipal issuance is considered a new debt issuance. Consequently, very limited issuance of tax-exempt commercial paper exists. Instead, issuers use either variablerate demand obligations (VRDOs) or a commercial paper/VRDO hybrid. 15. Answer the following questions. (a) Explain how an inverse-floating-rate municipal bond can be created. A common type of derivative security is one in which two classes of securities, a floating-rate 177 security and an inverse-floating-rate bond, are created from a fixed-rate bond. The sum of the interest paid on the floater and inverse floater (plus fees associated with the auction) must always equal the sum of the fixed-rate bond from which they were created. Inverse floaters can be created in one of three ways. First, a municipal dealer can buy in the secondary market a fixed-rate municipal bond and place it in a trust. The trust then issues a floater and an inverse floater. The second method is similar to the first except that the municipal dealer uses a newly issued municipal bond to create a floater and an inverse floater. The third method is to create an inverse floater without the need to create a floater. This is done using the municipal swaps. (b) Who determines the leverage of an inverse floater? The dealer determines the leverage of an inverse floater by choosing the ratio of floaters to inverse floaters. For example, an investment banking firm may purchase $100 million of the underlying bond in the secondary market and issue $50 million of floaters and $50 million of inverse floaters. The dealer may opt for a 60/40 or any other split. The split of floaters/inverse floaters determines the leverage of the inverse floaters and thus affects its price volatility when interest rates change. (c) What is the duration of an inverse floater? The duration of an inverse floater is a multiple of the underlying fixed-rate issue from which it was created. The multiple is determined by the leverage. To date, the most popular split of floaters and inverse floaters has been 50/50. In such instances, the inverse floater will have double the duration of the fixed-rate bond from which it is created. Determination of the leverage will be set based on the desires of investors at the time of the transaction. 16. For years, observers and analysts of the debt market believed that municipal securities were free of any risk of default. Why do most people now believe that municipal debt can carry a substantial amount of credit or default risk? Although municipal bonds at one time were considered second in safety only to U.S. Treasury securities, today there are new concerns about the credit risks of municipal securities. The first concern came out of the New York City billion-dollar financial crisis in 1975. This financial crisis sent a loud and clear warning to market participants in general —regardless of supposedly ironclad protection for the bondholder, when issuers such as large cities have severe financial difficulties, the financial stakes of public employee unions, vendors, and community groups may be dominant forces in balancing budgets. This reality was reinforced by the federal bankruptcy law that took effect in October 1979, which made it easier for the issuer of a municipal security to go into bankruptcy. The second reason for concern about municipal securities credit risk is the proliferation in this market of innovative financing techniques to secure new bond issues. It is not possible to determine in advance the probable legal outcome if the newer financing mechanisms were to be 178 challenged in court. This is illustrated most dramatically by the bonds of the Washington Public Power Supply System (WPPSS), where bondholder rights to certain revenues were not upheld by the highest court in the state of Washington. The two major commercial rating companies gave their highest ratings to these bonds in the early 1980s. While these high-quality ratings were in effect, WPPSS sold more than $8 billion in long-term bonds. By 1986 more than $2 billion of these bonds were in default. 17. Answer the following questions. (a) What is the equivalent taxable yield for an investor facing a 40% marginal tax rate, and who can purchase a tax-exempt municipal bond with a yield of 7.2? A common yield measure used to compare the yield on a tax-exempt municipal bond with a comparable taxable bond is the equivalent taxable yield. The equivalent taxable yield is computed as follows: equivalent taxable yield = tax-exempt yield . (1 marginal tax rate) In our problem, we assume that an investor in the 40% marginal tax bracket is considering the acquisition of a tax-exempt municipal bond that offers a yield of 7.2%. Inserting our values into our equation gives: equivalent taxable yield = 0.072 = 0.1200 = 12.00%. (1 0.40) (b) What are the limitations of using the equivalent taxable yield as a measure of relative value of a tax-exempt bond versus a taxable bond? When computing the equivalent taxable yield, the traditionally computed yield to maturity is not the tax-exempt yield if the issue is selling at a discount because only the coupon interest is exempt from federal income taxes. Instead, the yield to maturity after an assumed tax rate on the capital gain is computed and used in the numerator of the formula that computes the equivalent taxable yield. Also, as described below, one must realize that the effects of other taxes can also pose problems when comparing tax-exempt bonds versus taxable bonds. Because of the tax-exempt feature of municipal bonds, the yield on municipal bonds is less than that on Treasuries with the same maturity. Bonds of municipal issuers located in certain states yield considerably less than issues of identical credit quality that come from other states that trade in the general market. One reason for this is that states often exempt interest from in-state issues from state and local personal income taxes, whereas interest from out-of-state issues is generally not exempt. Consequently, in states with high income taxes, such as New York and California, strong investor demand for in-state issues will reduce their yields relative to bonds of issuers located in states where state and local income taxes are not important considerations (e.g., Florida). 179 18. Answer the following questions. (a) What is typically the benchmark yield curve in the municipal bond market? In the municipal bond market, several benchmark curves exist. In general, a benchmark yield curve is constructed for AAA-quality-rated state general obligation bonds. (b) What can you say about the typical relationship between the yield on short-term and long-term municipal bonds? In the Treasury and corporate bond markets, it is not unusual to find at different times either upward, downward or flat shapes for the yield curve. In general, the municipal yield curve is positively sloped indicating that short-term bonds have lower yields than long-term bonds. The most likely explanation is a maturity premium although other reasons could be present including expectations about inflation and supply versus demand considerations. 19. How does the steepness of the Treasury yield curve compare with that of the municipal yield curve? Assume slopes for both Treasury bonds and municipal bonds are upward sloping. If so, then a steeper municipal yield curve implies that yields for longer term municipal bonds increase more rapidly than for Treasury bonds. This could be caused if certain factors are more prominent in the municipal bond market. For example, if longer term municipal bonds are in shorter supply compared to Treasury bonds, then this factor could lead to greater yields for longer term maturities for municipal bonds. Consequently, a steeper upward sloping yield curve for municipal bonds would result. Similarly, if longer term municipal bonds are seen as increasing more rapidly in terms of credit risk with longer maturities, then the upward slope for yield curves for municipal bonds would be steeper. Finally, investing in municipal securities exposes investors to the same qualitative risks as investing in corporate bonds, with the additional risk that a change in the tax law may affect the price of municipal securities adversely. Since the impact can be greater for longer term maturities, this could cause yield curve for municipal bonds to be steeper. 20. Explain why the market for taxable municipal bonds competes for investors with the corporate bond market. Like the corporate bond market, taxable municipal bonds are bonds whose interests are taxed at the federal income tax level. Thus, investors are going to look at the risk and return trade-off to determine which bond they prefer. Because there is no tax advantage, investors will expect a higher return for a lower rated bond regardless of whether it is a municipal or corporate bond. For either a municipal or corporate bond, their yields must be higher than for another tax-exempt municipal bond. Also, their yields must be higher than the yield on U.S. government bonds because an investor faces credit risk by investing in either bond. 180