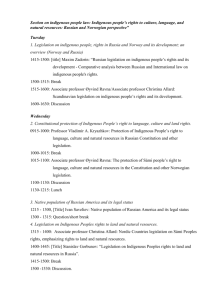

- the United Nations

advertisement