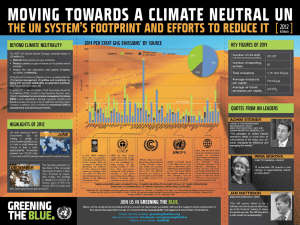

Evaluation of the Smog-Causing Emission Regulations in the

advertisement