environmental awareness/hazardous waste workbook

advertisement

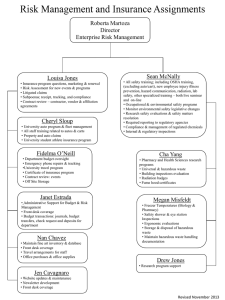

ENVIRONMENTAL AWARENESS/HAZARDOUS WASTE WORKBOOK Course Introduction 2 Environmental Laws 2 Generation and Handling Hazardous Waste 5 Universal Waste 11 Costs of Managing Hazardous Waste 14 Water and Air Pollution 15 Industrial Hygiene Standards 17 Course Conclusion 18 Glossary of Terms 19 Learning Activity 22 ENVIRONMENTAL AWARENESS HAZARDOUS WASTE WORKBOOK INTRODUCTION From the middle 1970s through the present, Congress has enacted many laws that have affected the way industry deals with the waste that is created. Universities are considered an industry under environmental laws. These laws are designed to protect life and the environment so that future generations will be able to enjoy the benefits of all our natural resources and not look back and curse us or be penalized for our lack of foresight. I will now introduce the laws that directly affect the Company and how we manage the waste products produced from our campus setting. RESOURCE CONSERVATION AND RECOVERY ACT The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) is considered to be the most far-reaching regulatory program ever undertaken by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The RCRA was enacted in October 1976, and was amended in 1980, and again in 1984. RCRA regulations have significantly changed university practices for treatment, storage, and disposal of hazardous waste. In addition, The State of Texas has generated and established its own set of rules and regulations that exceed the federal laws for hazardous waste management. Since the enactment of the RCRA, extensive regulation-laden requirements have affected universities. These regulations are designed to maintain safe work practices and preserve the environment. The regulations also provide for stiff criminal and financial penalties that have already caused some companies to dissolve because they could not or would not comply. Most people have come to realize that the hazardous wastes generated as part of our modern economy pose problems that must be brought under control to preserve the environment and quality of life as we know it. It has been estimated that approximately 250 to 275 million tons of hazardous waste are produced annually in the United States. The EPA believes that only a small percentage of this waste is handled in an environmentally acceptable way. The EPA has found that the mismanagement of hazardous waste causes the following types of environmental damage: pollution of groundwater, contamination of surface 2 waters, pollution of the air, fires or explosions, poisoning of humans and animals via the food chain, and poisoning of humans and animals via direct contact. It is believed that there are thousands of abandoned hazardous waste disposal sites across the country that have not been discovered, including over a hundred sites in Texas. Whether they are the result of blatant disregard for regulations or simply the result of disposal practices that were considered proper in the past, these sites pose serious problems, especially for groundwater contamination and threat to public health. While the magnitude of the overall environmental problem is unknown, there is little question that universities, businesses, cities, and federal and state agencies have disposed of hazardous wastes in ways that are now recognized to be inadequate to fully protect public health and the environment. In fact the EPA has uncovered some of these sites within the City of Houston. Cleanup projects have been initiated to remove and properly dispose of the contaminated materials. Thus disposal and burial practices that were acceptable in the past are now costing millions of dollars for cleanup and proper disposal. THE RCRA HAZARDOUS WASTE PROGRAM The goal of the RCRA hazardous waste program is to regulate and manage all aspects of hazardous waste from the time it is generated to the time it is disposed of properly. This is commonly known as "cradle-to-grave" management. Those who are managing solid wastes are required to identify wastes that are hazardous, and then manage that hazardous waste at the large quantity generator facility in accordance with RCRA regulations. WASTE DEFINITIONS The scope of the RCRA is governed by the definitions of two key terms: "solid waste" and "hazardous waste." Commonplace words take on different meanings because of the new definitions written directly into the RCRA law by Congress. Thus, there can be little or no "private" interpretation of what the terms mean. SOLID WASTE DEFINITION Congress defines solid waste in RCRA, Section 1004 (27), as being: "any garbage, refuse, sludge from a waste treatment plant, or air pollution control facility and other discarded material, including solid, liquid, semi-solid, or contained gaseous material, resulting from industrial, commercial, mining, and agricultural operations, and from community activities..."(italics added). This definition encompasses more than the standard definition of "solid." HAZARDOUS WASTE DEFINITION 3 As specified in RCRA, Section 1004 (5), Congress defined hazardous waste as "a solid waste, or combination of solid wastes, which because of its quantity, concentration, or physical, chemical, or infectious characteristics may: a) cause, or significantly contribute to an increase in mortality or an increase in serious irreversible, or incapacitating reversible, illness; or b) pose a substantial present or potential hazard to human health or the environment when improperly treated, stored, transported, or disposed of, or otherwise managed." The EPA has established criteria to identify hazardous wastes and has listed them by name. However, not all chemicals that can be hazardous are on this list. Therefore, the EPA identified characteristics that would further identify those hazardous wastes that were not listed by name. Many factors were considered including toxicity, potential for accumulation in tissue, flammability, corrosiveness, and other hazardous characteristics. With this information, the EPA established four hazardous waste characteristics. These are waste substances that are: ignitable, corrosive, reactive and toxic. It is important to understand that these characteristics and their definitions are the basis for federal and state regulations, as well as Company policies and procedures that deal with hazardous waste. IGNITABLE (40 CFR 261.21) see Appendix A: page 4. A solid waste is deemed to exhibit the characteristics of ignitability if it meets one of the four descriptions: 1. A liquid with a flash point of less than 60oCelsius(140oF). 2. A non-liquid that, under normal conditions, can cause fire through friction absorption of moisture, or spontaneous chemical changes and that burns vigorously and persistently. 3. An ignitable compressed gas as defined by 49 CFR 173.300. 4. An oxidizer as defined by 49 CFR 173.15. Examples of each of these ignitable hazardous wastes are as follows: (1) Methyl Ethyl Ketone (MEK), (2) Aluminum Powder (Al), (3) Propane, and (4) Ammonium Nitrate (Fertilizer). CORROSIVE (40 CFR 261.22) see Appendix A: page 4. The corrosivity characteristic was established as a safeguard against hazardous wastes capable of corroding through metal containers that would result in the wastes escaping into the environment. Wastes with a pH at either the high or low end of the scale can harm human tissue and aquatic life, and may react dangerously with other wastes. Therefore, a solid waste is deemed corrosive if it is: 1. Aqueous and has a pH of 2.0 or lower, or a pH of 12.5 or higher, or 2. A liquid that corrodes steel at a rate greater than 6.35 millimeters (0.250 inches) per year at a test temperature of 130oF. 4 Examples are: (1) Sulfuric Acid with a pH < 2.0 and sodium hydroxide with a pH>12.5 and (2) photo fixer solution from a photography laboratory. REACTIVE (40 CFR 261.23) see appendix A: page 4. The EPA identified reactivity characteristics of hazardous waste to regulate wastes that are extremely unstable and have a tendency to react violently or explode when being handled or stored. A waste is considered reactive if it has any of the following properties: 1. Normally unstable and readily undergoes violent changes without detonating. 2. Reacts violently with water. 3. Forms explosive mixtures with water. 4. Forms toxic gases, vapors, or fumes when mixed with water. 5. A cyanide or sulfide-bearing waste that gives off toxic gases, vapors, or fumes under normal conditions. 6. Detonates or explodes when ignited or heated under pressure. 7. Capable of detonation or explosive decomposition under normal conditions. 8. A Class A or B explosive. TOXICITY CHARACTERISTIC LEACHING PROCEDURE (TCLP) (40 CFR 261.24) see Appendix A: pages 5 and 6. The EPA decided that one of the most alarming dangers posed by hazardous wastes was the migration of toxic substances (arsenic, barium, lead, MEK, DDT, etc.) from landfill disposal sites into the water table. Consequently, the TCLP test is designed to identify wastes that are likely to leach toxic levels of certain substances into groundwater when improperly controlled. The TCLP Toxicity test described in 40 CFR 261 Appendix II, is a specific test that duplicates the leaching action of a substance under controlled means, thus giving an indication of whether or not the substance would threaten groundwater. Maximum allowable concentrations are set so that safe levels can be identified. Using these definitions and characteristics, the EPA developed the following three questions to help identify hazardous wastes: 1. Does the solid waste exhibit a hazardous waste characteristic (ignitable, corrosive, reactive, or TCLP toxic)? 2. Has the solid waste been found to be fatal in humans in low doses or, in the absence of human data, has it been shown to be dangerous in animal studies? 3. Does the solid waste contain any of the toxic constituents identified and listed by the EPA? WASTE CATEGORIES Based on the previous criteria, the EPA then established the following three categories of hazardous wastes: 5 1. Nonspecific source hazardous wastes (e.g., spent non-halogenated solvents, toluene, methyl ethyl ketone), 40 CFR 261.31. 2. Specific source hazardous wastes (e.g., bottom sediment sludge from the treatment of wastewaters from wood preserving), 40 CFR 261.32. 3. Discarded commercial chemical products, and all off-specifications species, containers, and spill residues, 40 CFR 261.33. GENERATION AND HANDLING OF HAZARDOUS WASTE Those involved with hazardous waste must carefully adhere to the "cradle-to-grave' philosophy. When proper care is taken, there is little or no chance for hazardous waste to become a threat to life or to the environment. RCRA HAZARDS The field of hazardous waste covers such a wide spectrum that the RCRA separated hazardous waste activities into four categories: 1. hazardous waste generation, 2. hazardous waste storage, 3. hazardous waste transportation, and 4. hazardous waste disposal. HAZARDOUS WASTE GENERATION A "generator" of hazardous waste is anyone or any organization that produces a hazardous waste(s) that can be identified or listed in 40 CFR 261.33-.33. This can be an individual, a company, university, or any government body, agency, or trust. The definition of a generator refers specifically to a particular site of generation. Thus, a university system with several campuses can be a multiple generator and must meet RCRA requirements separately for each campus. The EPA definition of a generator does not distinguish between a company that produces hazardous waste frequently and one that does not. Being a generator is not restricted to only the universities involved in generating the hazardous waste. Those companies that handle hazardous wastes in various stages can also become "generators." For example, this could be a transporter (trucking company) that has an accident that results in a spill. HAZARDOUS WASTE STORAGE The EPA allows a large quantity generator to store its hazardous wastes on-site for a period up to 90 days without obtaining a permit to act as a storage facility. A small quantity generator may have up to 180 days to store waste, but this generally doesn't apply to the Company. The time restriction applies, regardless of whether the wastes will be treated or disposed of on-site, or taken to an off-site treatment, storage, or disposal (T/S/D) facility. Labels that identify the material as hazardous waste, the material name, and the date must be attached to the outside of the container. Once a designated container is filled, all of the hazardous waste it contains must be transported to an off-site storage, treatment, or disposal facility within 90 days. 6 However, in cases of unforeseen or uncontrollable circumstances, it is possible to get a temporary extension of 30 days if hazardous waste must be stored for more than the original 90 day period. Nevertheless, a general rule is that the generator becomes an operator of a storage facility, by definition, if the wastes are stored on-site for longer than 90 days. This may cause the generator to become subject to sanctions for failure to have a RCRA storage permit. For remote waste generation sites on campus (laboratory, shop, etc.) a satellite accumulation station (SAS) may be set up. A SAS is governed by very specific rules regarding labeling, inspections, etc. The advantage, however, is that wastes can be collected and stored in the SAS without regard to the 90 day clock. Only 55 gallons of non-acute hazardous waste may be collected at a time. Within 3 days of attaining the 55 gallon limit, or when the SAS is no longer needed for accumulation, the waste must be moved to the 90 day storage area. HAZARDOUS WASTE HANDLING AND DISPOSAL Hazardous waste handling is a variety of steps that includes waste identification, segregation, and preparation. Also, it includes satellite accumulation stations (SAS), material inspection and pickup, transportation, material sorting, labeling, preparation, temporary storage requirements, documentation system, manifest paperwork, and shipment. RCRA Section 3001 requires the EPA to establish standards applicable to generators of hazardous waste as follows: 1. Record keeping that identifies the quantity, constituents, and disposition of hazardous waste 2. Labeling of containers used to store, transport, or dispose of hazardous waste 3. Use of appropriate containers 4. Furnishing of information regarding a generator's hazardous waste to persons who transport, treat, store, or dispose of such waste 5. Use of a manifest system and any other reasonable means necessary to ensure the proper disposal of hazardous waste 6. Submission of reports to the EPA or Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission (TNRCC) that identify the quantity and disposition of hazardous waste. The Risk Management Department has the responsibility to carry out the actual steps for shipment of hazardous wastes. The department collects, combines, and stores waste materials less than 90 days in accordance with current EPA regulations. The waste is packaged in accordance with the specific requirements of the treatment, storage, or disposal (T/S/D) facility and the Department of Transportation (DOT). Labels are clearly marked and the contents are identified. MANIFEST SYSTEM The RCRA requires the use of a manifest system to verify that hazardous waste destined for offsite storage or disposal actually reaches its destination. The manifest is the paperwork/documentation that tracks the hazardous waste from its point of generation to its point of disposal. This is in line with the "cradle-to-grave" management philosophy. 7 The Risk Management Department completes a Uniform Hazardous Waste Manifest that controls each shipment of hazardous waste. With the manifest filled out and documented, the hazardous waste can be moved off site. Information to be included on the manifest includes the name, EPA identification number, and address of the generator, the Department of Transportation (DOT) description of the waste, the quantity being transported, the name and EPA identification numbers of the transportation company, and the name and address of the EPA-authorized facility that will receive the hazardous waste. Phone numbers of the transporter and the T/S/D facility must also be listed, along with emergency response information. The emergency response information includes names of responsible persons, their telephone numbers, spill response guides, treatment standards, etc. An important aspect of the manifest system is the requirement that both a primary authorized T/S/D facility be identified to receive the hazardous waste. If the hazardous waste cannot be delivered to one of the designated facilities, the transporter must contact the generator who may either direct the transporter to another authorized facility or have the waste returned. The licensed carrier signs the manifest and ships the hazardous waste to an EPA - approved T/S/D facility. The generator copy of the manifest is retained by the Risk Management Department upon completion of the pickup. The remaining copies are forwarded to the T/S/D facility with the shipment for completion. The fully completed manifest must then be returned to the Company from the disposal facility within 45 days of shipment. If it is not, the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission must be notified. Usually the Risk Management Department contacts the disposer at 35 days if the manifest has not been returned. All correspondence and records are filed for future reference. Mistakes on a manifest that are not corrected can become an offense punishable by fine. The manifest stands as a record of all persons or organizations who handled a particular hazardous waste shipment. It records the chain of accountability for disposal of the waste. TREATMENT, STORAGE, OR DISPOSAL FACILITIES The RCRA has an expanded definition of what a T/S/D facility is. It covers any type structures and /or improvements that are put on land (as well as the land itself) that are to be used in managing any form of hazardous waste. HAZARDOUS WASTE TREATMENT A facility is defined as a hazardous waste "treatment" facility if it uses: "Any method, technique, or process, including neutralization, designed to change the physical, chemical, or biological character or composition of any hazardous waste so as to neutralize such waste, or so as to recover energy or material resources from the waste, or so as to render such waste nonhazardous, or less hazardous; safer to transport, store, or dispose of; or amenable for recovery, amenable for storage, or reduced in volume. (40 CFR 260.10(a))" Therefore, if the purpose of the facility is to alter or change the waste to a neutral or less hazardous substance, regardless of the method used, it is a treatment facility. 8 HAZARDOUS WASTE STORAGE A "storage" facility is one that is used to temporarily hold or store hazardous waste that will eventually be treated at, disposed of, or stored at another facility. HAZARDOUS WASTE DISPOSAL FACILITY A facility is considered a "disposal" facility if it is used for: "The discharge, deposit, injection, dumping, spilling, leaking, or placing of any solid waste into or on any land or water so that such solid waste or hazardous waste or any constituent thereof may enter the environment or be emitted into the air or discharged into any water, including groundwater. (40 CFR 260)” The disposal facility is considered the "grave" for hazardous wastes. CONTAINERS Containers are important because it is difficult to handle hazardous materials without them; but, not just any type will do. Hazardous waste containers must meet EPA and Department of Transportation specifications. The Company uses 55 and 30- gallon metal and plastic drums, and soft-pack (fiberboard and polyethylene) containers; the latter are primarily used for materials that will be incinerated. Containers are required to be in good condition and need to be handled so that there will not be any ruptures or leaks caused. If leaks occur, the contents must be moved into another container and proper spill procedures followed. Containers must be kept closed during all aspects of storage. Covers and lids must be on containers and/or funnels. If they are not closed, it is a fineable offense. Inspections for leaks and container deterioration must be made on a weekly basis. In addition, RCRA regulations require a secondary containment system under container storage areas. The secondary containment system must be capable of holding and collecting any spills, leaks, or accumulated rainfall. Specifically, the containment system must be designed to include: 1. A base underlying the containers that are sufficiently impervious to hold any wastes or accumulated precipitation for removal. 2. A system to remove liquids from leaks, spills, and rainfall, unless the containers are elevated. 3. Sufficient capacity to contain 10% of the volume of all the containers, or the volume of the largest container, whichever is greater. 4. A method for preventing or removing run-on into the containment system, and for promptly removing accumulated liquids from spills and leaks. The Company gathers hazardous waste when required by the generator on a daily basis. The generator must have completed the Company Hazardous Waste course and complete the Company chemical waste disposal forms. 9 HAZARDOUS WASTE DISPOSAL METHODS Disposal practices are very specifically outlined in the RCRA regulations. Environmental protection is the top priority in disposal; therefore, adequate safety measures are required for any disposal operation starting with the type of container used and ending with the type of disposal method the laws will allow. The five EPA-authorized disposal practices are: surface impoundment, landfill, incineration, underground injection wells and recycling. SURFACE IMPOUNDMENT A surface impoundment is a "natural topographic depression, man-made excavation, or diked area formed primarily of earthen materials" that is designed to hold liquid or semi-liquid wastes. A synthetic liner is usually required to prevent seepage of hazardous waste into the ground. LANDFILLS A landfill is defined as "a disposal facility or part of a facility where hazardous waste is placed in or on land and which is not a land treatment facility, a surface impoundment, or an injection well." (40 CFR 260.10) Use of a landfill has been the most common means of disposal for hazardous wastes. It has a high risk factor for environmental damage; therefore, the use of landfill disposal for hazardous waste is extensively monitored and regulated under the RCRA by the EPA. Landfills have two basic types of environmental danger. First, mismanagement that results in the mixing of reactive, ignitable, or incompatible hazardous wastes can result in fires, explosions, or toxic fumes. Second, runoff from landfills and erosion can contaminate the soil, and ground and surface waters. Liquids cannot be disposed of in landfills. It is important that all free liquids in a waste be stabilized. As of August 8, 1990, ignitable, corrosive, or reactive wastes cannot be disposed of in a landfill unless the waste meets specific treatment standards. INCINERATORS An incinerator is a special type of furnace that consumes the waste leaving little or no residue. There are several types of incinerators that use different methods (e.g., rotary kiln, fluidized bed, liquid injection). Before incinerating a hazardous waste, the operator must conduct a waste analysis to determine what type of pollutant could or would be emitted. The analysis must determine the heating value, type of waste content, and concentration of toxic metals. Hazardous waste may not be fed into an incinerator unless the incinerator is operating at its required temperature. Inspection of combustion and emission controls, stack emissions, the incinerator, and associated equipment are also required periodically. 10 There are three performance standards listed in 40 CFR 264 for a hazardous material incinerator to legally operate: 1. A destruction and removal efficiency rate of 99.99% must be achieved for each hazardous substance. 2. Materials containing more than 0.5% chlorine must have 99% of the hydrogen chloride removed from the exhaust gases. 3. The incinerator may not emit particulates exceeding 180 milligrams per cubic meter (180 mg/M3). UNDERGROUND INJECTION WELLS The EPA allows underground injection as a form of disposal for treated wastes. The regulations classify injection practices into five categories, or classes of wells, for regulatory treatment: Class I-Wells used for injection of hazardous wastes, other than Class IV wells, and industrial and municipal disposal wells that inject below all underground sources of drinking water. Class II - Oil and gas production and storage wells. Class III - Special process injection wells, such as those related to mineral mining, energy recovery, and gasification of oil shale. Class IV - Wells used by generators of hazardous or radioactive waste or hazardous waste management facilities where the waste is injected into or above a formation which, within one-quarter mile of the well, contains an underground source of drinking water. Class V - All other injection wells. Technical criteria and standards are specified for each class of well. These criteria and standards are designed to provide appropriate protection of underground water supplies. Generally, the EPA has banned the injection of hazardous wastes into, above, or within one-quarter mile of an underground source of drinking water. (40 CFR 144.13) RECYCLING WASTES The EPA has allowed certain hazardous wastes to be used as fuels to recover or create energy. Such hazardous waste fuels must be used in industrial-type boilers and furnaces. Containers must be labeled with a warning that identifies the hazardous wastes that are in the fuel. Metal recovery and reclamation of spent lead/acid batteries is also authorized. Oils are recycled to remove contaminants and are used again. Current recycling efforts at the Company include: paper recycling, used oil collection points, and the CHEMSWAP program. Future programs to recycle materials are currently being considered. UNIVERSAL WASTE 11 Currently Universal Waste in Texas are: 1. Batteries, as specified in 40 CFR 273.2 2. Pesticides, as specified in 40 CFR 273.3 3. Mercury containing equipment, including thermostats, as specified in 40 CFR 273.4 4. Lamps (i.e. light bulbs), as specified in 40 CFR 273.5 5. Paint and paint-related waste, as defined in 30 TAC 335.262(b) On July 28, 2006, Texas adopted the Universal Waste designation for Mercury-containing equipment through incorporation by reference of the EPA rule that adds mercury-containing equipment to the list of universal waste. STATUS FOR UNIVERSAL WASTE HANDLERS There are separate requirements for small quantity handlers and large quantity handlers managing universal waste: Small quantity handler—any person who accumulates < 5,000 kilograms of all universal waste Large quantity handler—any person who accumulates ≥ 5,000 kilograms of all universal waste MANAGEMENT OF UNIVERSAL WASTE Small quantity generators are not required to notify the U.S. EPA of universal waste handling activities, however, large quantity handlers must receive and EPA identification number before meeting the 5,000 kg storage limit. According to 40 CFR 273.13 & 273.33 Universal Waste must be managed in a way that prevents releases to the environment. As far as labeling Universal Waste containers, according to 40 CFR 273.14 & 273.34 the containers must be clearly marked as follows: “Universal Waste Batteries” “Universal Waste Pesticides” “Universal Waste Mercury-Containing Thermostats” “Universal Waste Lamps” “Universal Waste—Paint and Paint Related Wastes” Generators may store Universal Waste for up to one year. The generator may be allowed extra time provided they have proper proof of the need to exceed the one year time limit. OFF-SITE SHIPMENTS OF UNIVERSAL WASTE According to 40 CFR 273.18 & 273.38 Universal Waste must be shipped either to another universal waste handler, a destination facility, or a foreign destination. Universal Waste is not required to be on a Uniform Hazardous Waste Manifest. Small quantity generators are not required to track Universal waste shipments. Large quantity generators must keep a record of all Universal waste shipments. 12 QUALIFICATIONS OF UNIVERSAL WASTE Paint and Paint—Related Wastes are determined by the following qualifications: Used or unused paint Spent solvents used in painting Personal Protective Equipment, contaminated rags, gloves, and debris resulting from painting operations Coating waste paint, overspray, overrun paints, paint filters, paint booth stripping materials, paint sludges from water-wash curtains Cleanup residues from spills of paint Cleanup residues from paintings and paint-removal activities Other paint-related wastes generated as a result of the removal of paint A Lamp is defined in 40 CFR 260.10 & 273.9 as the bulb or tube portion of an electric lighting device. A lamp is specifically designed to produce radiant energy most often in the ultraviolet, invisible, and infrared regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Examples of common universal waste lamps include, but are not limited to, fluorescent, high-intensity, discharge, neon, mercury vapor, high-pressure sodium, and metal halide lamps. Qualifications of Lamp as Universal Waste are specified in 40 CFR 273 in that it must first meet the definition of a waste, then meet the definition of a hazardous waste. COSTS OF MANAGING HAZARDOUS WASTE MATERIAL Hazardous waste disposal practices that were proper in the past have proven to be detrimental to the environment in the present. Even though some past practices were done innocently, we are paying a stiff price today in lost resources and massive cleanup costs. ROUTINE HANDLING AND DISPOSAL COSTS Costs to properly store, transport, and dispose of hazardous waste are skyrocketing. the Company pays between $90 and $750 to dispose of one 55-gallon drum Considering the Risk Management Department will dispose of hundreds of drums from the Company campus, ten's of thousands of dollars are spent annually to compliance with state and federal regulations. Typically of waste. each year remain in At present, the Company is making efforts to ensure that all wastes regulated by the EPA are handled and disposed of properly. Hazardous wastes are moved from Satellite Accumulation Sites (SAS) to the Hazardous Waste Facility (HWF) in polyethylene trays to contain any spills due to breakage or corrosion. Hazardous waste is lab-packed at the HWF after segregation and characterization of the waste into metal drums. Two types of containers are used and each has advantages and disadvantages. Metal drums generally have a $75 each handling fee at incinerators because they cause a lot of slag or are cleaned by triple rinsing. Fiberboard and polyethylene containers cause less ash in incinerators, but cannot be used in landfill disposal. Fiberboard containers cannot be used for liquids. Metal containers can be stored outdoors, but usually need to be repainted and relabeled before shipping. 13 Fiberboard must be stored indoors, out of the weather, because water deteriorates the fiberboard quickly. Costs for transportation of these wastes continually mounts because of increases in diesel fuel, hazardous waste disposal surcharges, etc., and regulatory costs. The average cost is about $3 per loaded mile to truck hazardous waste to disposal sites. MIXTURE RULE ECONOMICS Mixing chemicals can prove dangerous and costly. If you consider that virtually any amount of hazardous material will contaminate any nonhazardous material, the costs will grow. It takes only one-fifth of one drop of a hazardous chemical to contaminate an entire drum of liquid material. Obviously, by mixing chemicals, additional costs are created in disposing of what was a nonhazardous waste, but by federal definition, is now hazardous waste. It is imperative that each employee practice safe, conservative measures when dealing with hazardous waste materials. Any errors in mixing the wrong chemicals together can be very costly, not only in terms of handling, but in terms of health and fire hazards as well. Costs can skyrocket. For example, mixing methyl ethyl ketone (MEK) with methylene chloride (MeCl2) changes the characteristics of MeCl2, making it flammable, and thus unsuitable for recycling. The cost for disposal of the drum and its contents jumps from $90 to $350. Another costly procedure is lab analysis to determine the contents of unlabeled containers. When unlabeled containers are left at accumulation points, it can cost $2000 for a full analysis to find out what is in the container. Across the country, hazardous waste disposal costs are increasing 10% each year. When selfinflicted cost increases are added to this, the disposal gets very expensive. The following table will give an understanding of the money the Company spends to comply with hazardous waste legislation and be a good neighbor. WASTE DISPOSAL RATES A. The chemical waste disposal fees assessed by category are: 1. Category Category 1 (Lecture Cylinder, Gas Cylinders, Aerosols) Fee 1000 Measure each 2. Category 2 (Explosives, Organic Peroxides, Shock/ Heat Sensitive) 800 each 3. Category 3 (Mercury Debris, Mercury Salts, Lead Compounds, 50 pound (solids) gallon 166 14 Pesticides & Reactives) 4. Category 4 (Acids, Bases, Corrosives, Flammables, Non-Hazardous, ORMs, Oxidizers, & Poisons) (liquids) 23.89 gallon B. If a chemical waste is a mixture of two categories; the highest price per category shall be charged. Risk Management Department ships hazardous waste on a monthly basis. With the costs per container and the frequency with which they must be shipped, it is easy to see how expensive it is to properly dispose of the hazardous wastes that are produced at the Company. WATER and AIR POLLUTION, ETC. The major cause of oil polluting our water is the average, day-to-day spill that occurs in harbors, rivers, lakes, and streams. Two-thirds of all oil spills occur during routine operations as the result of human error. Whether a tank is allowed to overflow during transfer operations, a valve has sprung a leak at a refinery seeping oil into the river, or a hose has burst, the main cause of the oil pollution problem remains the same: lack of follow through, and lack of planning at local levels. Almost 5% of the substances that are released into water consist of 12 chemicals regulated by the EPA and the states. The 12 chemicals are phosphoric acid, sodium hydroxide, sulfuric acid, nitric acid, hydrochloric acid, ammonium sulfate, ammonia, ammonium nitrate, chlorine, arsenic, aluminum oxide, and methanol. LAND Most of the land releases reported in the Toxic Releases Inventory (TRI) are waste disposal that fall into several categories, with different levels of regulatory control. The largest volumes of toxic chemicals released to the land result from mining activities. The EPA is currently developing a regulatory program under the RCRA for the large volume of waste generated by mining activities. AIR POLLUTION STANDARDS The Clean Air Act (CAA) Amendments of 1990 established the Environmental Protection Agency's right to implement the air program in Texas. The Clean Air Act defined nonattainment as geographic areas which do not meet one or more of the National Ambient Air Quality 15 Standards for the criteria pollutants. The areas of nonattainment in Texas and its ozone area classification are: Dallas-Ft. Worth (moderate), El Paso, Beaumont/Port Arthur (serious), and Houston-Galveston/Brazoria (severe). The severe nonattainment in Harris County is due to 1,310,378 lbs./day total emissions of volatile organic compounds. The major source category breakdown consists of 47% point sources (ex. stacks), 36% mobile sources (ex. automobiles) and 17% area sources. The Company is in an ozone nonattainment area and will be required to initiate an Employer Trip Reduction Program and other Clean Air Act requirements. The purpose of an Employer Trip Reduction Program is to reduce the number of vehicles used during rush hour commuting periods by increasing the average passenger occupancy by 25%. New vehicles purchased by the Company must be capable of using alternate fuels. The nonattainment vehicle inspection/maintenance program requires tailpipe emissions tests with computerized analyzers and an anti-tampering of pollution control inspection of all vehicles in the HoustonGalveston/Brazoria area. Tailpipe emissions reduction will make the air we breath healthier as we continue to drive more and use more fuels. The CWA helped to set up the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) which cover six common pollutants: Particulate Matter Ozone Sulfur Dioxide Carbon Monoxide Lead Oxides of Nitrogen The acid rain provisions of the Clean Air Act requires the reduction of sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides emissions and clean coal technology by utility power plants and other facilities with boilers, heaters, turbines, and internal combustion engines. SPILL PREVENTION, CONTROL, AND COUNTERMEASURE RULE The Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasure (SPCC) rule includes requirements for oil spill prevention, preparedness, and response to prevent oil discharges to navigable waters and adjoining shorelines. The rule requires specific facilities to prepare, amend, and implement SPCC Plans. The SPCC rule is part of the Oil Pollution Prevention regulation, which also includes the Facility Response Plan (FRP) rule. GROUNDWATER CONTAMINATION Over the next 20 years, one of the most serious problems the nation will face is groundwater contamination. This includes not only lakes polluted by acid rain and streams contaminated by leaching of hazardous and solid waste disposal sites, but almost every major deep water system will have some degree of natural or man-made contamination. Recent studies by federal, state, and other organizations in the private and public sectors indicate there is a major potential for health problems of epidemic proportions associated with hazardous 16 materials, chemicals, and wastes leaching into our water supply from improperly managed sanitary landfills, abandoned and improperly managed hazardous waste disposal sites, the continued illegal disposal of hazardous and toxic waste, and leaking underground storage tanks. CLEAN WATER ACT (CWA) The main objective of the CWA is to restore and maintain the chemical, physical and biological integrity of the nation’s waters. Some of the CWA programs include: Establish water quality standards for all bodies of water Set technology-based effluent limitations in discharge permits Require the development of Spill Prevention, Control and Countermeasures (SPCC) Plans Control non-point sources of pollution (stormwater) There are various discharges to municipal sewer authorities that may require pretreatment and /or permits: Swimming pool drainage Medical or infectious waste Detergents, surface-active agents which may cause excessive foaming Photographic wastewater Laboratory wastewater Non-contact cooling waster/boiler blowdown Animal or vegetable based oils, fats or greases Wastewaters with a pH lower than 5.5 or higher than 10.5 STORMWATER POLLUTION Stormwater runoff is generated when precipitation from rain and snowmelt events flows over land or impervious surfaces and does not percolate into the ground. As the runoff flows over the land or impervious surfaces (paved streets, parking lots, and building rooftops), it accumulates debris, chemicals, sediment or other pollutants that could adversely affect water quality if the runoff is discharged untreated. The primary method to control stormwater discharges is the use of best management practices (BMPs). In addition, most stormwater discharges are considered point sources and require coverage under an NPDES (National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System) permit. INDUSTRIAL HYGIENE STANDARDS Permissible exposure levels (PELs) have been established by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Compliance with the PELs must be achieved by implementing administrative or engineering controls whenever feasible. When these controls are not effective in achieving full compliance, protective equipment, such as respirators or other personal safety equipment, must be used. To remain in compliance with the PELs, directors and managers must keep abreast of future OSHA publications in the Federal Register that affect facility operations. 17 In affected work areas, compliance with changing PELs will require additional studies, such as air testing (environmental monitoring in work areas where new PELs are more stringent, old PEL 1000 ppm, new PEL 750 ppm; etc.). The redesign of ventilation systems not presently capable of reducing air contaminants to the appropriate compliance levels may also be required. In many cases, material substitution may be an option. Compliance with the new PEL listings will not be easy and will affect many areas in the university community. Manufacturers, importers, and distributors which we buy chemicals from must prepare and distribute new MSDS for chemicals for which new and more stringent PELs are issued. Users must ensure that the new information is included. RIGHT TO KNOW Under the Emergency Planning and Community Right-To-Know Act, manufacturing facilities with ten or more employees that produced, processed, or used certain amounts of any or more then 300 toxic chemicals were required to report their annual releases of those chemicals to the EPA by July 1, 1988. To date, the EPA has proposed assessments of more than $2.5 million in penalties against companies that have failed to report their emissions. COURSE CONCLUSION This course has introduced the efforts and goals that the Company have made in becoming an environmentally aware and responsible neighbor. The effect of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act on hazardous waste has been presented so that Company employees can be more conscious of the responsibility to correctly handle hazardous waste products at home and at work. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS By: Blake Payne impartial completion of, Advanced Studies in Industrial Hygiene and Safety INDH 4436 under the guidance Dr. Magdy Akladios. 18 APPENDIX GLOSSARY OF TERMS Abatement—Reducing the degree or intensity of, or eliminating pollution. Air Contaminant—Any particulate matter, gas or combination thereof, other than water vapor or natural air. Air Pollutant—Any substance in air which could, if in high enough concentration, harm man, other animals, vegetation, or material. Pollutants may include almost any natural or artificial composition of matter of matter capable of being airborne. They may be in the form of solid particles, liquid droplets, gases, or in combinations of these forms. Generally, they fall into two main groups: 1. Those emitted directly from identifiable sources and 2. Those produced in the air by interaction between two or more primary pollutants, or by reaction with normal atmospheric constituents, with or without photoactivation. Exclusive of pollen, fog, and dust, which are of natural origin, about 100 contaminants have been identified and fall into the following categories: solids, sulfur compounds, volatile organic chemicals, nitrogen compounds, oxygen compounds, halogen compounds, radioactive compounds, and odors. Air Pollution—The presence of contaminant or pollutant substances in the air that do not disperse properly and consequently interfere with human health or welfare, or produce other harmful environmental effects. Air Quality Criteria—The levels of pollution and lengths of exposure above which adverse health and welfare effects may occur. Ambient Air—Any unconfined portion of the atmosphere: open air, surrounding air. Attainment Area—An area considered to have air quality as good as or better than the national ambient air quality standards as defined in the Clean Air Act. An area may be an attainment area for one pollutant and a nonattainment area for others. BACT—(Best Available Control Technology) An emission limitation based on the maximum degree of emission reduction which is achievable through application of production processes and available methods, systems, and techniques. In no event does Best Available Control Technology permit emissions in excess of those allowed under any applicable Clean Air Act provisions. Use of the Best Available Control Technology concept is allowable on a case-bycase basis for major new or modified emissions sources in attainment areas and applies to each regulated air pollutant. 19 Carcinogen—Any substance that can cause or contribute to the production of cancer. Cleanup—Action taken to deal with a release or threat of release of a hazardous substance that could affect humans and/or the environment. Contaminant—Any physical, chemical, biological, or radiological substance or matter that has an adverse affect on air, water, or soil. Criteria Pollutants—The 1970 amendments to the Clean Air Act required the Environmental Protection Agency to set National Ambient Air Quality Standards for certain pollutants known to be hazardous to human health. The Environmental Protection Agency has identified and set standards to protect human health and welfare for six pollutants: ozone, carbon monoxide, total suspended particulates, sulfur dioxide, lead, and nitrogen oxide. Disposal—Final placement or destruction of toxic, radioactive, or other wastes, surplus or banned pesticides or other chemicals; polluted soils; and drums containing hazardous materials from removal actions or accidental releases. Hazardous Air Pollutants—Air pollutants which are not covered by ambient air quality standards but which, as defined in the Clean Air Act, may reasonably be expected to cause or contribute to irreversible illness or death. Such pollutants include asbestos, beryllium, mercury, benzene, coke oven emissions, radionuclides, and vinyl chloride. Hazardous Substance- -Any material that poses a threat to human health and/or the environment. Any substance named by the Environmental Protection Agency to be reported if a designated quantity of the substance is spilled in the waters of the United States or if otherwise emitted into the environment. Hazardous Waste—By-products of society that can pose a substantial or potential hazard to human health or the environment when improperly managed. Possesses at least one of four characteristics (ignitability, corrosivity, reactivity, or toxicity), or appears on special Environmental Protection Agency lists. Indoor Air Pollution—Chemical, physical, or biological contaminants in indoor air. Landfills—Sanitary landfills are land disposal sites for non-hazardous solid wastes at which the waste is spread in layers, compacted to the smallest practical volume, and cover material applied at the end of each operating day. Secure chemical landfills are disposal sites for hazardous waste. They are selected and designed to minimize the chance of release of hazardous substances into the environment. Listed Wastes—Wastes listed as hazardous under Resource Conservation and Recovery Act but which have not been subjected to the Toxic Characteristics Listing Process because the dangers they present are considered self-evident. 20 Material Safety Data Sheet—A compilation of information required under the Occupational Safety (MSDS) and Health Administration Hazard Communication Standard on the identity of hazardous chemicals, health and physical hazards, exposure limits, and precautions. Section 311 of the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act requires facilities to submit material safety data sheets under certain circumstances. National Ambient Air—Air quality standards set by the Environmental Protection Agency Quality Standards for an air pollutant that may cause an increase in deaths or in (NAAQS) serious irreversible or incapacitating illness. Primary standards are designed to protect human health, secondary standards to protect public welfare. National Pollution Discharge—A provision of the Clean Water Act which prohibits discharge of Elimination System pollutants into the waters of the United States unless a special permit (NPDES) is issued by the Environmental Protection Agency, a state, or a tribal government on an Indian reservation. Nonattainment Area—Geographic area which does not meet one or more of the National Ambient Air Quality Standards for the criteria pollutants designated in the Clean Air Act. Ozone Depletion—Destruction of the stratospheric ozone layer which shields the earth from ultraviolet radiation harmful to biological life. This destruction of ozone is caused by the breakdown of certain chlorine-and/or bromine-containing compounds which break down when they reach the stratosphere and catalytically destroy ozone molecules. Pollution—The presence of matter or energy whose nature, location or quantity produces the undesired environmental effects. Reportable Quantity—The quantity of a hazardous substance that triggers a report under (RQ) the Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA). If a substance is released in amounts exceeding its reportable quantity, the release must be reported to the National Response Center, the State Emergency Response Commission, and community emergency coordinators for areas likely to be affected. Toxic Pollutants—Materials contaminating the environment that cause death, disease, and/or birth defects in organisms that ingest or absorb them. The quantities and length of exposure necessary to cause these effects can vary widely. Toxic Substance—A chemical or mixture that may present an unreasonable risk of injury to health or the environment. 21 LEARNING ACTIVITY Name: 1. The four forms of a solid waste as defined by Congress in the RCRA include: a. garbage, refuse, sludge, and discarded solid, liquid, semi-solid or gaseous materials b. liquid, non-liquid, oxidizers, toxins c. ignitables, corrosives, reactives, toxins d. non-liquids that can cause fire through friction 2. A hazardous waste may cause the environment. a. health benefits, growth or to human health or b. mortality, irreversible damage c. no damage, pollution d. solid waste build up 3. The four characteristics of a hazardous waste include: a. solids, liquids, gases, sludge b. sludge, garbage, pollutants, solids c. ignitable, corrosive, reactive, toxic d. paints, lamps, batteries, toxins 4. The three categories of hazardous waste include: a. ignitable, lamps, batteries b. Non-specific, specific, and discarded c. solids, liquids, toxins 5. A generator may store hazardous waste for days before it has to be transported. a. 90 days 22 b. 50 days c. 20 days d. 150 days 6. A "generator" is defined as: a. produces garbage, sludge that can be discarded b. anyone, or any organization that produces a hazardous waste(s) that can be identified or listed in 40 CFR 261.33 c. generates lamps, batteries and toxins d. generates toxins and disposes of garbage 7. The five disposal methods of hazardous waste include: a. dumping, draining, landfill, buildup, release b. surface impoundment, landfill, incineration, underground injection wells, and recycling c. releasing, dumping, manifest, shipment, burning 8. The two types of containers used to transport hazardous waste are: a. 20 and 50 gallon iron drums b. 50 and 75 gallon plastic drums c. 30 and 55 gallon metal and plastic drums 9. Mixing chemicals can prove and . a. safe and cheap b. dangerous and costly c. effective and legal 10. The Houston-Galveston/Brazoria area is classified as a severe area. a. attainment 23 b. nonattainment c. ozone 11. Universal Waste include: a. paint and paint-related materials, batteries, mercury containing thermostats, pesticides, lamps b. solids, liquids, flammable gasses c. garbage, solids, lamps 12. What is the main objective of the Clean Water Act (CWA)? a. restore and maintain the chemical, physical and biological integrity of the nation’s waters b. reduce stormwater runoff c. reduce emissions 24