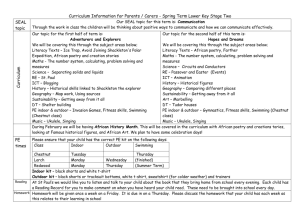

Identification and Classification

advertisement