IMECE98 - Tufts University

advertisement

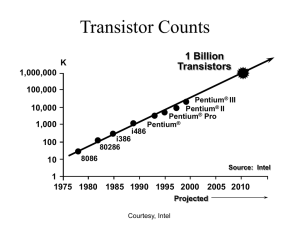

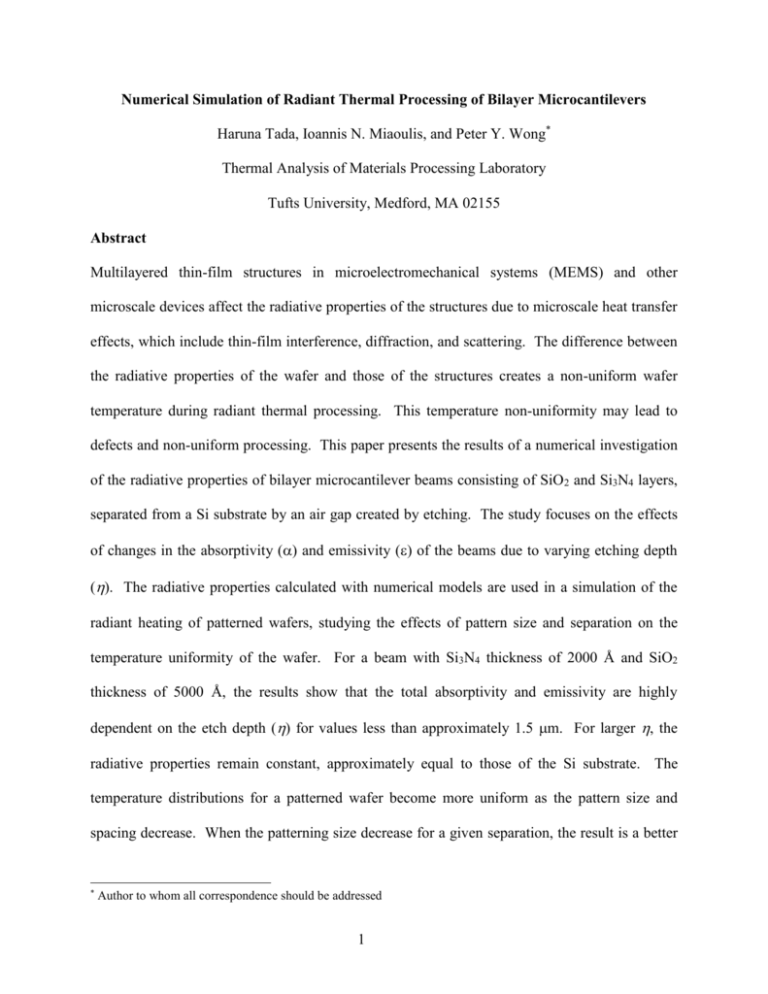

Numerical Simulation of Radiant Thermal Processing of Bilayer Microcantilevers Haruna Tada, Ioannis N. Miaoulis, and Peter Y. Wong* Thermal Analysis of Materials Processing Laboratory Tufts University, Medford, MA 02155 Abstract Multilayered thin-film structures in microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) and other microscale devices affect the radiative properties of the structures due to microscale heat transfer effects, which include thin-film interference, diffraction, and scattering. The difference between the radiative properties of the wafer and those of the structures creates a non-uniform wafer temperature during radiant thermal processing. This temperature non-uniformity may lead to defects and non-uniform processing. This paper presents the results of a numerical investigation of the radiative properties of bilayer microcantilever beams consisting of SiO2 and Si3N4 layers, separated from a Si substrate by an air gap created by etching. The study focuses on the effects of changes in the absorptivity () and emissivity () of the beams due to varying etching depth (). The radiative properties calculated with numerical models are used in a simulation of the radiant heating of patterned wafers, studying the effects of pattern size and separation on the temperature uniformity of the wafer. For a beam with Si3N4 thickness of 2000 Å and SiO2 thickness of 5000 Å, the results show that the total absorptivity and emissivity are highly dependent on the etch depth () for values less than approximately 1.5 m. For larger , the radiative properties remain constant, approximately equal to those of the Si substrate. The temperature distributions for a patterned wafer become more uniform as the pattern size and spacing decrease. When the patterning size decrease for a given separation, the result is a better * Author to whom all correspondence should be addressed 1 thermal interaction between the die and the wafer, resulting in a smaller temperature gradient. This, however, creates a large temperature difference between the wafer patterning area and the outer edge region, which results in an increased temperature gradient along the wafer edge. These heat transfer effects should be taken into consideration when creating fabrication mask sets for radiant thermal processing to design a pattern layout that would best avoid the problems caused by thermal gradients. 2 1. Introduction The fabrication of microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) and other microscale devices can cause the surface radiative properties to change. The changes are due to microscale radiative effects, which include optical phenomena such as thin-film interference, diffraction, and scattering. The non-uniformity of the radiative properties strongly affects the temperature distribution on the wafer, particularly during radiative heating processes. Understanding the changes in local wafer temperature is important both for MEMS fabrication processes and for a new area of MEMS sensor application during thermal processing. During fabrication, it is generally desired that temperature remain uniform over the wafer. The presence of patterns can create large temperature gradients within the wafer resulting in a variety of problems including thermal stress. As new MEMS devices are designed and new fabrication methods are developed, radiant thermal processing may be implemented to achieve higher temperatures and reduced thermal budgets. For example, some cases of chemical vapor deposition (CVD) processes are implemented at temperatures of up to 1200 °C (Ohring, 1992). In MEMS sensor application, the temperature gradients become critical when the devices are used as temperature sensors. If the sensors have radiative properties different than those of the surrounding wafer region, the temperature recorded by the device can be an inaccurate representation of the actual temperature of the substrate. This paper presents the results of a numerical investigation of the radiative heating of microscale cantilever beams. Cantilever beams are widely used for material characterization such as stress and mechanical properties measurements (Obermeier, 1997). Multilayered cantilever beams can be used as temperature sensors by taking advantage of the difference in the thermal expansion coefficients of the two beam materials, which will cause the beam to deflect at 3 elevated temperatures (Tada, 1998). In addition, analysis of the radiative properties of cantilever structures can be used for any other suspended multilayered structure such as membranes. The radiative properties for the cantilever beams are used in simulations of rapid thermal processing (RTP) of patterned wafers. The deviation of the beam properties from those of the surrounding wafer region induces temperature gradients over the wafer. The effects of size and spacing of the patterns on the degree of temperature uniformity are discussed. The results from this study aid in developing the optimal pattern layout and processing conditions to maintain the best temperature uniformity over the wafer. 2. Numerical Modeling The cantilever beam studied in this paper is a wide (~10 m) bilayered beam, separated from the substrate by an air gap created from etching (Figure 1). The top and bottom layers of the beam consist of Si3N4 and SiO2, with thicknesses t1 and t2, respectively. The etching depth, , determines the thickness of the air gap. The combination of the beam and air gap is a multilayered thin-film structure, resulting in optical interference effects when the film thicknesses are of the order of wavelength of incident radiation. Figure 2 shows the thin-film cantilever beam interference effect in the cantilever beam. Si3N4 SiO2 The incident radiation is partially reflected at the first interface, and the remaining portion enters the Si3N4 layer. This radiation is then partially reflected at the substrate Si Si3N4 - SiO2 interface. The radiation will Figure 1. Side view of cantilever beam structure 4 be partially reflected and transmitted at each incident radiation reflected radiation subsequent interface, and the net reflectivity t1 can be calculated by adding all the rays exiting SiO2 t2 Si3N4 from the Si3N4- Air interface, taking into g account the phase differences between the rays. The constructive or gap destructive Si interference between the exiting rays due to the absorbed radiation difference in optical path length results in a spectral reflectivity that is highly dependent on Figure 2. Thin-film interference within the cantilever beam the wavelength. The spectral reflectivity is a function of film thickness, index of refraction of film, and the wavelength. For this study, the film thicknesses used were t1 = 2000 Å and t2 = 5000 Å, with varying etch depth, . The indices of refraction for the materials were 2.0, 1.55, and 3.6 for Si3N4, SiO2, and Si, respectively. It was assumed in the model that the SiO2 and Si3N4 layers were transparent, and the Si substrate was opaque. The opaque substrate assumed that all radiation entering this layer was absorbed. This assumption is valid for highly doped wafers and for wafer temperatures above 600 °C (Wong, 1994). The numerical model for determining the radiative properties of beams first calculates the normal spectral reflectivity, , of the multilayered thin-film structure as a function of wavelength, . The model uses the matrix method to solve the Maxwell's equations at each interface within the cantilever beam structure (Heavens, 1995). The total normal reflectivity is then calculated, which represents the ratio of the reflected energy and the incident energy over all wavelengths: 5 () E b, (T, )d 0 , (1) E b, (T, )d 0 where Eb,(T,) is the blackbody emissive power, given by: E b , (T, ) C1 exp( C 2 / T) 1 5 , (2) where T is the temperature of the emitting body, and C1 and C2 are 3.742×108 W·m4/m2 and 1.439×104m·K, respectively (Incropera and De Witt, 1990). For an opaque substrate (no transmission), the spectral normal absorptivity, , is equal to 1 - , and the total normal absorptivity can be found by: (1 ) E b, d 0 . (3) E b, d 0 Here, Eb, is calculated using the temperature of the incident radiation source. Furthermore, since the spectral emissivity, , is equal to at any wavelength, the total normal emissivity, , can also be found from Eqn. 3 by using the temperature of the emitting surface for Eb,. The total radiative properties are needed for heat transfer calculations with thermal radiative bodies such as wafers under radiant heating. In other cases, the spectral properties may be more important. For example, in laser heating where the incident energy consists of one wavelength only, the spectral absorptivity at the wavelength of the laser must be used to determine the absorbed energy. In such case, although the spectral absorptivity is used to calculate the radiant energy absorbed by the material, the total emissivity must be used to find the amount of radiant heat lost to the environment. 6 The total radiant properties are used in a numerical y model of the thermal radiative heating of patterned wafers. The wafer, shown in Figure 3, has a radius R, and x r a patterning area bounded by a smaller radius, r. The R patterns consist of a series of cantilever beams confined wafer within a square die of sides L. The die is repeated on the patterning area patterning area of the wafer with a spacing of S. The Figure 3. Wafer geometry patterns are shown in Figures 4 and 5, on the die scale and wafer scale, respectively. beams substrate L L S Figure 4. Die pattern L Figure 5. Die layout on the wafer Figure 6 shows the isometric view of the cantilever beam, showing the different multilayer structures in the die area. There are three different layer structures within the die area: the beam, the wafer material (SiO2 on Si), and bare silicon. The fabrication processes of the cantilever beam are shown in Figure 7, with the masks for steps 1 and 2 indicated by the arrows. The beam is fabricated by first depositing a layer of SiO2 on the wafer, excluding the area bounded by the mask. Next, a layer of Si3N4 is deposited on the area indicated by the mask. Finally, the bare silicon area is etched to release the cantilever beam. Due to the SiO2 deposition 7 in step 1, there is a uniform layer of Si3N4 SiO2 SiO2 on the surrounding wafer area. The backside of the wafer is also covered by SiO2 of the same thickness Si to avoid wafer curvature due to Figure 6. Isometric view of cantilever beam thermal stress within the films. Because of the low thermal resistance of a single beam, the die area is modeled as having uniform properties, approximated by taking the weighted average of the wafer, beam, and Si properties: Xdie = Cwafer·Xwafer + Cbeam·Xbeam + CSi·XSi (4) where X is some property and C is the percentage of total area that has the surface property of the material indicated by the subscript. The temperature distribution of the wafer is found using finite difference equations of second-order accuracy. The wafer is first discretized into a grid, shown in Figure 8. The control volume indicating the heat transfer for an interior node is shown in Figure 9. The grid spacing and cell thicknesses are designated as d and z, respectively, with the cell Process top view side view SiO2 (1) SiO2 deposition Si (2) Si3N4 deposition Si3N4 SiO2 Si (3) etching Figure 7. Bilayer cantilever beam fabrication processes 8 thickness equal to the wafer thickness. The heat transfer in j the control volume consists of three parts: conductive heat, absorbed radiative heat, and emitted radiative heat. The conductive heat going into the control volume can be expressed by: q cond,n i kA C (Tn - T0), d (5) Figure 8. Finite difference grid where AC is the conducting area, L is the distance between nodes, T0 and Tn are the temperatures of nodes 0 and n, respectively, and k is the thermal conductivity of the interface. For interior cells, AC and L are d·z and d, respectively (Incropera and De Witt, 1990). The wafer is considered to be radiatively heated by a series of linear tungsten-halogen lamps from the top. The amount of lamp emission that is absorbed by the control volume is given by: qrad,in = wafer f lamp AA Tlamp4 (6) where wafer is the wafer absorptivity, f is the shape factor from the lamps to the cell, lamp qrad,outtop qrad,in qcond,1 is the lamp emissivity, Tlamp is the lamp temperature, and is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, 5.67×10-8 W/m2K4. qcond,4 qcond,2 AA is the absorbing area, equal to d2 for interior cells. The shape factor, f, was approximated to be 0.1 on all cells, which is a typical value for 9 z qcond,3 qrad,outbottom Figure 9. Control volume of interior cell this RTP system. The wafer loses heat by emitting radiation from its surfaces. The emitted radiation is a combination of emissions from top and bottom surfaces of the control volume: qrad, out = celltop AEtop Tcell4 + cellbottom AEbottom Tcell4. (7) Here, cell is the emissivity of the cell, AE is the emitting area, and Tcell is the temperature of the cell. The emitting area for interior cells is equal to d2 for top and bottom. For cells at the edge or corner, the above equations are adjusted to account for the difference in areas for conductive and radiative heat transfer. In addition, the cells along the wafer edge radiate heat from its sides as well as from the top and bottom surfaces. The energy balance was solved at each cell iteratively using underrelaxation (Patankar, 1980), with convergence defined as Tk - Tk-1 110-6, where k denotes the iteration steps. The wafer dimensions used in this study were R = 38 mm, r = 32 mm and z = 0.4 mm, with a grid spacing of d = 0.25 mm. The dimensions L and S were varied to study the effects of various pattern layouts on the temperature uniformity of the wafer. Lamp temperature of T L = 2500K and emissivity of L = 0.4 were used for the radiation source. The conductivity of the wafer was estimated to be k = 1.5 W/m·K, and the radiative properties of silicon were Si = 0.6 and Si = 0.6. The radiative property of the wafer surface, consisting of a 5000 Å SiO 2 film on Si substrate, were found to be wafer = 0.81 and wafer = 0.75 using the numerical method discussed above. 3. Results and Discussion The spectral reflectivities for of 1 m (×) and 2 m (°) are shown in Figure 10, along with the normalized blackbody emission for a temperature of 1000 K. This temperature roughly 10 corresponds to the temperature of the wafer from the numerical simulation of wafer temperature distribution. The large fluctuations in the spectral reflectivities are due to the constructive and destructive interference of the different rays of reflected light. Figure 11 shows the total normal absorptivity (°) and emissivity (×) of the cantilever beam structure for different values of . Recall, from Eqn.3, that the total normal emissivity can be found by dividing the area under (1)·Eb by the area under Eb,, with Eb, calculated using the temperature of the emitting surface. When the peaks of the spectral reflectivity curve coincides with the region of high blackbody emission, the result is a low total emissivity, as seen in the case of = 1 m. If, at high values of Eb,, the spectral reflectivity is low, the result is a high total normal emissivity. The spectral reflectivity curve for = 2 m remains low through most of the peak emission range, resulting in a high total normal emissivity seen in Figure 11. The total normal emissivity of the beams stabilizes for 1.5 m. Structures with large has rapidly fluctuating spectral reflectivities at high Eb, region, similar to what is seen in 2 m in Figure 10. Due to the large number of peaks within the high Eb, region, integration over has an overall averaging effect, eliminating the effects due to individual peaks. 0.7 1.00 0.6 0.75 0.5 0.4 0.50 Eb (Eb,)max 0.3 0.25 0.2 0.1 0.00 1 2 3 4 5 6 etch depth ( m) 7 8 9 10 Figure 10. Spectral reflectivities of multilayered cantilever beam for = 1m (×) and 2 m (°), and the normalized blackbody emission for 700 K (—) 11 0.70 40 922 K 921 0.65 total normal absorptivity 30 920 919 y (mm) 0.60 918 20 total normal emissivity 0.55 917 916 0.50 0.0 1.0 915 10 2.0 3.0 etch depth (m) 4.0 5.0 910 900 Figure 11. Total normal absorptivity (°) and0emissivity (×) of multilayered cantilever beams 0 The same effects are 10 20 x (mm) 30 40 Figure 12. Temperature profile in a uniform wafer responsible for the changes in the total normal absorptivity; however, the Eb, curve corresponding to the absorptivity is evaluated at a lamp temperature of 2500 K. The difference between and for 1.5 m comes from the difference between the Eb, curves for the two temperatures. The blackbody emission for 2500 K has more energy in the lower wavelength, having its peak at ~1.2 m as opposed to ~3 m for 700 K. The total normal absorptivity is strongly affected by the spectral reflectivities at lower wavelengths, creating a difference between the values of and . The wafer temperature distribution for a uniform wafer (i.e. no pattern) is shown in Figure 12; only the upper right quadrant of the wafer is shown due to symmetry. The axes show the wafer dimension in mm, and the scale shows temperature in K. A maximum temperature of 922.235 K is recorded at the center of the wafer. Within the patterning area, the wafer shows good temperature uniformity; the temperature at radius of 32 mm (at the edge of patterning area) is 921.639 K, only 0.596 K less than the center temperature. Outside of the patterning area, however, there is a large gradient due to the radiative cooling off the side of the wafer. 12 The patterned wafer uses die properties calculated from Eqn.4, using coefficients Cwafer = 0.32, Cbeam = 0.23, and CSi = 0.45. A beam of = 1 m is used in this model, which, from Fig.11, have radiative properties beam = 0.59 and beam = 0.54. The resulting die properties are die = 0.65 and die = 0.65. Table 1 summarizes the results from different values of L and S, and the temperature profiles for each case are shown in Figures 13 through 17. In each figure, the bar indicates the location at which the temperature gradients were found. The temperature distribution for Case 1, with L = 5 mm and S = 2 mm, is shown in Figure 13. The temperatures of the die area are lower than the surrounding wafer area due to the lower absorptivity of the die area. Figure 14 shows the temperature profile through a cross section of the wafer taken through the bottom row of dies. The temperature profile is compared against that of the uniform wafer. The minimum temperature at Point A was 915.623 K as indicated in Fig. 13. This temperature is 6.612 K less than the temperature at the corresponding point in the uniform wafer. Figure 14 indicates a large temperature difference between the center of the die (Point A) and the midpoint between two dies (Point B), indicated by the bar in Figure 13. For Case 1, this difference was 3.129 K, which translates into a temperature gradient of Table 1. Compilation of wafer temperatures for various L and S Case Figure L (mm) S (mm) Tmin (K) T between points A and B (K) 1 2 3 4 5 6 13 15a 15b 16a 16b 17 5 5 5 4 3 5 2 3 1 2 2 2 915.623 915.961 914.835 916.451 917.549 916.354 3.129 4.002 1.898 2.666 2.088 2.776 Cases 1 through 5 use Cwafer=0.32, Cbeam=0.23, and CSi=0.45; Case 6 uses Cwafer=0.57, Cbeam=0.14, and CSi=0.29. 13 Temperature gradient between points A and B (K/mm) 0.834 0.942 0.584 0.820 0.759 0.740 0.834 K/mm. 40 922 K 921 Figure 14 shows a sharp rise 920 30 in temperature at the edge of the y (mm) patterning area. The patterning area 919 918 20 917 has a low average temperature due to the lower absorptivity of the patterns. 916 915 10 910 A B Outside of this area, the average 900 0 0 temperature is higher. This differene between the average temperatures of 10 20 x (mm) 30 40 Figure 13. Temperature distribution for a patterned wafer with L=5mm and S=2mm the two regions result in a large temperature gradient at the edge of the patterning area. Figure 15 shows the temperature distributions for Cases 2 and 3. These cases investigate the effect of changing the die spacing, S. The minimum temperature at A for Cases 2 and 3 were 915.961 K and 914.835 K, respectively. In Case 2, a temperature difference of 4.002 K was found between A and B, indicating a temperature gradient of 0.942 K/mm. For Case 3, the temperature difference was 1.898 K, with a gradient of 0.584 K/mm. As S decreases from 3 mm to 1 mm, the minimum temperature decreases from 915.961 K at 3 mm, 915.623 K at 2mm,and 914.835 K at 1 mm. This indicates the patterning area of the wafer deviating farther away from the uniform wafer case, behaving more closely to the extreme case where the entire patterning area were made of the die material. The temperature gradients observed in each case indicates that as S decreases, the temperature gradient decreases as well. This can be expected since the thermal interaction between two dies is increased as the spacing decreases. Although the temperatures within the patterned wafer deviates farther from the uniform wafer case for 14 Temperature (K) 923.0 921.0 919.0 917.0 915.0 0.0 5.0 10.0 15.0 20.0 25.0 30.0 35.0 40 40 x (mm) 30 Figure 14. Temperature profile through a cross section of wafer for uniform wafer (—) 30 and L=5mm, S=2mm (×) 922 K 921 920 y (mm) y (mm) 919 20 918 20 917 916 10 915 10 A B 910 A B 0 900 0 0 10 20 x (mm) 30 40 0 (a) 10 20 x (mm) 30 40 (b) Figure 15. Temperature distributions for (a) Case 2 and (b) Case 3 decreasing S, the temperature gradients within the patterning area is smaller, indicating less local thermal stress and other problems related with temperature non-uniformities. The decrease in S is accompanied by a decrease in the temperature gradients within the patterning area; however, along the edge of the patterning area the temperature gradients increase for decreasing S. This is due to the overall reduced temperature of the patterning area for smaller S values creating a larger temperature difference between the die and the wafer area outside of the patterning area. 15 The effects of changing L can be seen in Figure 16, which shows the temperature distributions for Cases 4 and 5. The minimum temperatures found at A were 916.451 K and 917.549 K, respectively. There was a temperature gradient of 0.820 K/mm in Case 4, found from a temperature difference of 2.666 K between A and B. Case 5 has a maximum temperature gradient of 0.759 K/mm with a temperature difference of 2.088 K between the dies. The increase in temperatures at Point A that accompanies the decrease in L indicates that the temperatures in the patterning area are approaching those of the uniform wafer. The reduced temperature gradients in the patterning area seen with decreasing L are followed by a decrease in the temperature gradients along the edge of the patterning area. When L is reduced, the average temperature within the patterning area approaches that of the uniform wafer, resulting in a smaller temperature difference between the die and the outer wafer region. For any values of L, however, the temperature gradient at the edge of the patterning area is still larger than those within the patterning area. All the previous cases studied wafer patterns with the same die property. A change in the 40 40 40 30 30 y (mm) y (mm) 30 y (mm) 922 K 20 20 20 10 A B 0 0 10 20 x (mm) 30 40 0 10 0 0 (a) 920 920 919 919 918 918 915 A B 0 921 917 916 10 B 921 917 10 A 922 K 10 20 x (mm) (b) 20 x (mm) 30 910 915 900 910 40 30 916 900 40 Figure for 17. (a) Temperature Figure 16. Temperature distributions Case 4 anddistribution (b) Case 5 for Case 6 16 beam layouts within the die will change the coefficients Cbeam, Cwafer, and CSi in Eqn.4, affecting the radiative properties of the die area. It can be anticipated that if the spacing between the beams within the die is larger (i.e., Cwafer increases), the temperature distribution within the wafer should approach that of the uniform wafer. This effect is studied in Case 6, which uses C wafer = 0.57, Cbeam = 0.14, CSi = 0.29. The corresponding radiative properties are die = 0.68 and die = 0.71 for a cantilever beam with = 1 m. Figure 17 shows the resulting temperature profile for Case 6, using L = 5 mm and S = 2 mm. Figure 18 shows the cross sectional temperature profile for this case, along with that for Case 1 and the uniform wafer. Fig.18 clearly shows the raised temperature for Case 6; the minimum temperature in this case is 916.354 K as opposed to 615.623 K in Case 1. The temperature gradient is smaller as well, with a temperature difference of 2.776 K between A and B. The overall trends in the effects of changing L and S are an improved temperature uniformity within the patterning area as L and S decrease. However, along the edge of the patterning area, an increase in temperature gradient is observed for smaller S. During fabrication processes, it is generally desired that the temperature gradient within the patterning area to remain small to ensure uniform processing. A reduction in S will satisfy such condition; however, the large temperature gradient outside the patterning area caused by the small S may induce thermal stress and other unwanted effects along the outside edge of the wafer. The optimal combination of S and L must be determined for individual applications taking into account the relative importance of maintaining the temperature uniformity both within and outside the patterning area. 17 Temperature (K) 923.0 921.0 919.0 917.0 915.0 0.0 5.0 10.0 15.0 20.0 x (mm) 25.0 30.0 35.0 Figure 18. Temperature profile through a cross section of wafer for Case 1 (×), Case 6 (°), and uniform wafer (—) 4. Conclusion Maintaining the temperature uniformity over a wafer during device fabrication is generally desired to avoid the various problems caused by temperature gradients, including thermal stress and uneven processing parameters. When the process involves radiative heating, the temperature uniformity is greatly affected by the non-uniform radiative properties of the wafer created by the devices themselves. Fabricated components often include thin-films, which have radiative properties different from the surrounding areas of the wafer due to thin-film interference. The degree of influence that the devices have on the temperature profile of the wafer depends on their size, spacing, and the optical properties. This study focused on wafer pattern consisting of an array of bilayered cantilever beams, which are common structures in MEMS. The beams consist of SiO2 layer and Si3N4 layer, separated from Si substrate by an air gap created by etching. The absorptivity and emissivity of 18 the structure found for various etching depths indicate a nearly constant and , with values similar to those of the Si substrate, for. At lower values of , the properties change dramatically, deviating from the values for 1.5 m by as much as 7 %. The changes in radiative properties create large temperature non-uniformity in the wafer when a series of such structures are fabricated on a die and repeated over the wafer. The temperature gradient depends on the size of the die (L) and the spacing (S) between them. The general trend in the dependence is a decrease in temperature gradient (better temperature uniformity) as L and S decrease, within the patterning area of the wafer. When L and S are sufficiently small, the wafer temperature uniformity is maintained at a level comparable to that of a uniform wafer with no patterns, although the overall temperature may differ. The worst case scenario in die layout is when L is large, allowing the pattern to strongly affect the surrounding area, and S is also large, resulting in less thermal interaction between the neighboring dies. When the absorptivity is lower in the patterns than in the surrounding, the temperature gradients along the edge of the patterning area are larger than those within the area. A decrease in S, which results in a decrease in the temperature gradient within the patterning area, causes the gradients along the outside to increase. While the temperature gradient outside the patterning area may not be an issue in maintaining the uniform processing conditions, it can cause many negative effects such as thermal stress and wafer curvature. The optimal wafer layout must be determined while taking into consideration the relative importance of maintaining the temperature uniformity both inside and outside of the patterning area. 19 References Heavens, O.S., 1955, Optical Properties of Thin Solid Films (Butterworth, Washington, D.C.) pp. 46-95. Incropera, F. P. and De Witt, D. P., 1990, Introduction to Heat Transfer, Second Edition (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY) Obermeier, E., 1997, "Mechanical and Thermophysical Properties of Thin Film Materials for MEMS: Techniques and Devices," Mat. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc., Vol. 444, pp. 39-57. Ohring, M., 1992, The Materials Science of Thin Films (Academic Press, San Diego, CA) Patankar, S. V., 1980, Numerical Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow (Hemisphere Publishing Corporation, Washington) Tada, H., Abramson, A.R., Miaoulis, I.N., Wong, P.Y., Nieva, P., and Zavracky, P., 1998, "MEMS as Temperature Sensors During High Temperature Processing," submitted for the Proceedings of Symposium on Microelectromechanical Structures for Materials Research, Materials Research Society. Vandabeele, P., Maex, K., and De Keersmaecker, R., 1989, "Impact of Patterned Layers on Temperature Non-Uniformity During Rapid Thermal Processing for VLSI-Applications", 20 Proceedings of Symposium on Rapid Thermal Annealing/Chemical Vapor Deposition and Integrated Processing, Materials Research Society, Vol. 146, pp.149-160. Wong, P. Y., Hess, C. K, Miaoulis, I. N., 1992, "Thermal Radiation Modeling in Multilayer Thin Film Structures," International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, Vol. 35, pp. 3313-3321. Wong, P.Y. and Miaoulis, I.N., 1994, "Thermal Radiation Absorption Characteristics of Patterned Wafers During Rapid Thermal Processing," Materials Research Society, Vol. 342, pp. 395-400. 21