AGREED SUM AND SPECIFIC PERFORMANCE

advertisement

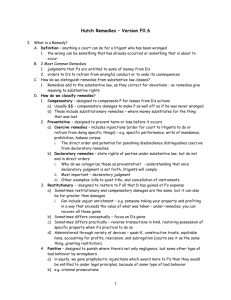

CONTRACT LECTURE 14 REMEDIES PART 2 C STRICKLAND Track/slide 1 In a previous lecture we considered the main remedy for breach of contract, that is, damages. In this lecture, we consider other remedies for breach of contract, namely: i. ii. iii. iv. an agreed sum specific performance injunctions, and, quantum meruit. We shall start then with an agreed sum. Track/slide 2 The claim for an agreed sum is a common law remedy so is available as or right. It usually means that the claimant is suing for the PRICE of the contract. It differs from a claim in damages in that: i. ii. iii. there is no need to prove loss, and so there is no need to worry about remoteness of damage nor to mitigate loss This is because when suing for the price the claimant is basically just enforcing a DEBT. Although, should the claimant want to, they can ask for the agreed sum and also any loss over and above the price. We might ask, why would anyone sue for the price only? Well, as we have mentioned, there is no need to prove loss or worry about mitigation and remoteness. In addition, the amount being claimed is known – it is a ‘liquidated sum’ (whereas the amount of damages is for the court to decide) and the case can get through court quite quickly. Track/slide 3 These rules can however sometimes result in what appears to be an abuse of the innocent party’s ‘rights’ following breach of contract. This can be seen in the case of White and Carter (Councils) Ltd v McGregor 1962, a House of Lords case. In this case the appellants who were advertising contractors had made a contract with the respondent, who owned a garage, to display adverts for the garage on council litter-bins for a period of 3 years. On the same day that the deal was made for renewal for a further 3 years of the advertising contract, the defendant said he had changed his mind and didn’t want to go ahead. This amounted to an anticipatory breach of contract. Despite this, the advertisers decided to go ahead with the contract and displayed the adverts for the 3 years and then brought an action for the ‘agreed sum’ for breach of contract. In the House of Lords it was held that the advertisers had been entitled to carry out the contract and could recover the full contract price. Lord Reid stated that in the case of an anticipatory breach the innocent party may either accept the repudiation and sue for damages or he may affirm the contract and then sue for an agreed sum, as the plaintiffs did here. Lord Reid stated that: i. since this was an action for an agreed sum, the contract price, the advertisers had no duty to try to mitigate their loss, by for example accepting the end of the contract and then trying to get another one. He also said that, ii. continued performance of the contract despite the anticipatory attempt at breach was permitted so long as the plaintiffs had a ‘legitimate’ interest in continuing with the contract, be this a financial interest or other interest. If there is no legitimate interest in continuing with the contract the plaintiff should accept the breach and sue for damages. His Lordship stated: ‘Here the respondent did not set out to prove that the appellants had no legitimate interest in completing the contract and claiming the contract price rather than claiming damages; there is nothing in the findings of fact to support such a case, and it seems improbable that any such case could have been proved. It is, in my judgment, impossible to say that the appellants should be deprived of their right to claim the contract price merely because the benefit to them, as against claiming damages and re-letting their advertising space, might be small in comparison with the loss to the respondent: that is the most that could be said in favour of the respondent. Parliament has on many occasions relieved parties from certain kinds of improvident or oppressive contracts, but the common law can only do that in very limited circumstances.’ His Lordship further said that iii. continued performance is only possible if this can be achieved without the co-operation of the other side – and clearly in this case this was possible. The actions of the advertisers do seem a little bizarre in this case and the case has been criticised – for instance, it has been said that even in an action for an agreed sum the plaintiffs should be required to mitigate. Track/slide 4 We can now consider the question of whether interest can be charged for late payment of the agreed sum. At common law the position would appear to be that the debtor only has to pay the actual price of the contract without interest. However, this common law position is usually avoided by either: i. an express term in the contract stating that interest will be charged for late payment or ii. application of the Late Payment of Commercial Debts (Interests) Act 1998 though this only applies to sale and supply contracts where both sides are acting ‘in the course of a business’. Track/slide 5 We can now move on to consider specific performance. First, we should remember that ‘damages’ for breach of contract are the main remedy for breach of contract. Specific performance is rare, other than in contracts for the sale of land. An order of specific performance is an equitable, and therefore discretionary remedy, that compels the actual performance of the contract. If the performance does not take place this amounts to contempt of court for which the person may be sent to prison or fined. The court may also sequester property. That the order of specific performance is only available as a ‘secondary’ remedy to damages is seen by Anson as a good thing because: i. when specific performance is ordered it relieves the claimant of any duty to try to mitigate loss, and, ii. it is less necessary these days since the courts are now better at assessing the amount of damages that can be awarded to compensate the innocent party Track/slide 6 Generally then, specific performance is only available where: i. ii. iii. iv. v. damages are not an adequate remedy, he who comes to equity comes with clean hands, the contract is not one for personal services, the contract would not take a lot of supervision to enforce, and where the performance to be enforced is clearly ascertainable. Track/slide 7 First then we shall consider the point that specific performance is only available where damages are not an adequate remedy. However, these days the scope of when it may be ordered is wider in that it may be ordered where it will ‘do more perfect and complete justice than an award of damages’. The key case here is Beswick v Beswick 1968. It was Lord Reid in the House of Lords that awarded specific performance to achieve a ‘just result’ in the circumstances of the case. Lord Pearce granted specific performance because he said it was a more ‘appropriate’ remedy. The extent to which this case means that specific performance is ‘generally available’ in unclear. Professor Treitel has suggested that whether or not it is granted depends on the ‘appropriateness’ of it in the circumstances of the case in hand. Let us consider what happened in this case. Peter Beswick operated a coal round and made a contract with his nephew that he would transfer the business to the nephew. One of the stipulations in the contract was that when Peter died, the nephew would pay Peter’s widow £5 a week for the rest of her life. When Peter died, the nephew only made one payment of £5 and then stopped. The widow sought to enforce the payments of the weekly £5 in her capacity as administratix of Peter’s estate and in her personal capacity. She was successful in gaining an order of specific performance from the House of Lords rather than damages. We can see why below. Track/slide 8 Lord Reid stated: ‘Applying what I have said to the circumstances of the present case, the respondent in her personal capacity has not right to sue, but she has a right as administratix of her late husband’s estate to require the appellant to perform his obligation under the agreement. He has refused to do so and he maintains that the respondent’s only right is to sue him for damages for breach of his contract. If that were so, I shall assume that he is right in maintaining that the administratix could then only recover nominal damages because his breach of contract has caused no loss to the estate of her deceased husband. If that were the only remedy available the result would be grossly unjust. It would mean that the appellant keeps the business which he bought and for which he has only paid a small part of the price which he agreed to pay. He would avoid paying the rest of the price, the annuity to the respondent, by paying a mere 40 shillings damages... The respondent ‘s second argument is that she is entitled in her capacity of administratix of her deceased husband’s estate to enforce the provision of the agreement for the benefit of herself in her personal capacity, and that a proper way of enforcing that provision is to order specific performance. That would produce a just result, and, unless there is some technical objection, I am of opinion that specific performance ought to be ordered. For the reasons given by your Lordships, I would reject the arguments submitted for the appellant that specific performance is not a possible remedy in this case.’ Track/slide 9 Lord Pearce disagreed with Lord Reid on the amount of damages that would be available for breach of contract but agreed on the availability of specific performance when he stated: ‘In the present case I think that the damages, if assessed, must be substantial. It is not necessary, however, to consider the amount of damages more closely since this is a case in which, as the Court of Appeal rightly decided, the more appropriate remedy is that of specific performance. the adminstratix is entitled, if she so preferes, to enforce the agreement rather than accept its repudiation, and specific performance is more convenient than an action for arrears of payment followed by separate actions as each sum falls due. Moreover, damages for breach would be a less appropriate remedy since the parties to the agreement were intending an annuity for a widow; and a lump sum of damages does not accord with this. And if (contrary to my view) the argument that a derisory sum of damages is all that can be obtained be right, the remedy of damages in this case is manifestly useless. The present case presents all the features which led the equity courts to apply their remedy of specific performance. The contract was for the sale of a business. The defendant could on his part clearly have obtained specific performance of it if Beswick senior or his adminstratix had defaulted. Mutuality is a ground in favour of specific performance.’ However, the court will refuse the order is they consider that the award of damages will put the plaintiff in as beneficial a position as if the contract had been specifically performed. Track/slide 10 Specific performance is also only available on the basis that ‘he who comes to equity comes with clean hands’ – one has to remember that specific performance is an equitable remedy and so equitable maxims apply. So, the court may refuse specific performance if it thinks the claimant’s behaviour has been ‘tricky’ or ‘unfair’. This equitable point was explored in Quadrant Visual Communications Ltd v Hutchinson Telephone (UK) Ltd 1993. The plaintiff’s appeal was against an order refusing specific performance of a contract and payment of £1.2263 million with interest. In the contract it specified that the sum was to be payable ‘free from any equity, cross claim, set off or other deduction whatsoever’. It was held that the words ‘any equity’ covered the concept of coming to equity with clean hands. However, it was also held that whilst this part of the contract might bind the parties to the contract, once the issue was before the court, then when specific performance has been requested, the court’s discretion to award it or not could not be fettered by reference to the contents of the contract. Otherwise, the court would simply be rubber stamping the contract. The appeal was dismissed. Track/slide 11 Specific performance is also only available if the contract is not one for personal services – if it is a contract for personal services then the courts are reluctant to order specific performance as it would be an infringement of personal liberty. The case of Page One Records Ltd v Britton 1968 shows the relationship between specific performance and injunctions [that usually order someone not to do something]. In this case the plaintiffs, Page one records, were the managers of the pop group ‘the Troggs’. In the contract between them and the Troggs it stated that the pop group would not employ anyone else as their manager for the 5 years of the life of the contract. When things turned sour between the two, the group sought to employ a new manager, Harvey Block Associates Ltd. Page one records therefore sought an injunction preventing them from doing this. The injunction was not granted because if it had it would have forced the group to keep page one as their manager and they had lost faith in them. Thus, the granting of the injunction would have had the same effect as if the court had ordered specific performance of the 5 year contract and it would not do so for such a personal service. Track/slide 12 Specific performance will also only be awarded when the performance of the contract does not require a lot of supervision – here we can look at 3 cases: Ryan v Mutual Tontine Westminster Chambers Assoc 1893 Posner v Scott-Lewis 1986 Co-operative Insurance Society Ltd v Argyll Stores (Holdings) Ltd 1997 In the Ryan case an order of specific performance was not granted - it would require too much supervision to ensure that a resident porter would be in attendance at all times at a block of flats as stated in the leases. In the Posner case however with similar facts an order of specific performance was granted. However, the Argyll case puts the Posner case in doubt and seems to support the approach in the Ryan case. In the Argyll case the defendant was a supermarket chain with a lease for a unit in the plaintiff’s shopping centre. The lease was for 35 years and they were to be open during the usual hours of business. The presence of this supermarket was very important to the success of the shopping centre as it would attract customers and help to support the smaller units. However, after less than 6 years, due to poor profits, the defendants closed the shop and moved out of the unit. The plaintiff sought specific performance of the contract requiring the shop to come back and keep trading. The House of Lords realised that damages were not an adequate remedy as it would be difficult to quantify the expectation losses over the remaining 19 years left to run on the lease. Despite this they refused the order of specific performance because: - it would be difficult to draft the order it would be difficult to supervise it it would in effect compel the defendants to carry on an uneconomic business. Track/slide 13 Finally, specific performance is only available where the performance expected is clearly ascertainable. If the contents of the contract are not clearly specified then it may be impossible for the court to order specific performance as they would not know exactly what to order. Thus in Wilson v Northampton and Banbury Railway Company 1874 the court did not order specific performance where the contract was to ‘construct a railway station’ with no reference to the nature, materials, style, dimensions or anything else. Track/slide 14 We can now move on to consider Injunctions. Injunctions are either PROHIBITORY or MANDATORY. Prohibitory ones are used to stop one side acting positively when the contract is designed to prevent positive action. Mandatory ones are used to compel some action. Both are equitable and discretionary. First then, we shall consider Prohibitory injunctions A prohibitory injunction may be granted when there is the breach of a negative contract or contract term. For example if the contract is NOT to carry on a certain trade or not to drive vehicles after a certain time at night, then if the person who promised not to do these things in the contract does in fact do them (acts positively) then a prohibitory injunction will normally be granted to prevent them from doing these things. In a contract for personal services, a prohibitory injunction may serve the purpose of encouraging the party in breach to actually perform the contract, though remember that it is rare for an order of specific performance for a personal contract. Track/slide 15 An interesting case is: Lumley v Wagner 1852 In this case the defendant agreed to sing at the plaintiff’s theatre and during a certain time frame she agreed not to sing anywhere else. Despite this, she then made a contract with someone else to sing at another theatre and refused to fulfil her original contract. The court refused to order specific performance of her positive contractual duty to sing at the plaintiff’s theatre, BUT, the court granted a prohibitory injunction to prevent her from breaching her promise not to sing anywhere else. Thus, in a subtle way, she was being encouraged to sing at the plaintiff’s theatre. Track/slide 16 The courts only apply the Lumley and Wagner use of injunctions where: i. the contract had the negative provision included as an express term, and, ii. the defendant is able to get some work to live off. If the effect of the injunction would be to give the defendant the choice of working for the plaintiff or not being able to work at all – then the courts won’t grant the injunction as it would in effect be achieving the same result as an order of specific performance. An interesting case is Warner Bros Pictures Inc v Nelson 1937. In this case the actress Bette Davis (Mrs Nelson) had a contract with Warner Bros to the effect that for a certain period she would ‘not render any similar services to any other person or engage in any other occupation’. Despite this she made a contract with another film company and Warner Bros sought an injunction to stop her working for them. At first instance it was held that although it would not be possible to grant an injunction to stop her from working for someone else in ‘any’ occupation [otherwise she could starve to death] it was possible to grant an injunction to stop her working ‘as an actress’ for someone else for the specified time. Track/slide 17 We can now make a few comments on Mandatory injunctions An example of when a mandatory injunction might be used is to make a landlord let tenants back if he evicted them in breach of their contract. They are thus used to restore the status quo that existed before the defendant’s breach of contract. Note, that under the Supreme Court Act 1981, ss 49and 50, the court has the power to award damages in addition to or in place of specific performance or an injunction. Such damages are assessed just like the common law damages are assessed. Track/slide 18 We can now make a few comments on Quantum meruit This is the principle dating from Planche v Colburn 1831 that where one party confers a benefit on another with the intention on both sides that the benefit will be paid for, then, in the absence of a contract, the party conferring the benefit on the other will be able to recover reasonable remuneration for what they have done. Thus, in British Steel Corporation v Cleveland Bridge and Engineering Co ltd 1984 the plaintiffs started work on a major construction project before the final contract was drawn up. Both sides had expected the contract to go ahead without any problems. However, the contract never materialised. The plaintiffs were allowed to succeed on a claim in quantum meruit for the work they had done. Quantum meruit does not normally operate where there is a contract because the parties will be bound by the actual terms of the contract. However, we have already noted that for an ‘entire’ contract, where the consumer pays for a job done, such as home improvements, once the work is complete, quantum meruit may apply. We looked first at Cutter v Powell when the widow could not get the wages of her deceased sailor husband for his work at sea before he died because the contract was an entire one and he did not complete the contract. We then noted how this harsh rule could be avoided when the claiminat had conferred a benefit on the defendant and the defendant had a real choice as to whether to accept the benefit or not. Thus, if a builder half completed a house and then abandoned the project in breach of contract, this would be the breach of an entire obligation and so no money would be due – in this case nothing would be due on a quantum meruit basis either because the defendant has no choice but to accept the work done. But, in the Sumpter v Hedges case we noted that the builder could recover in quantum meruit for the value of building materials he left when he abandoned his building project because the owner had had a choice of using the materials or returning them to the builder.