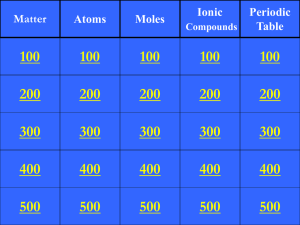

Alumina α-Al2O3 (ī10):

advertisement

Alumina α-Al2O3 (ī10): An ab-initio Examination of the Surface Electronic Structure Michael Vargas Dr. Nick Kioussis Abstract: First principles calculations were run on bulk and the (ī10) surface of α-Al2O3 in order to examine the electronic structures and structural relaxations. The Materials Studio package was used, specifically the program CASTEP, utilizing Perdew Burke Ernzerhof exchange-correlation pseudo-potentials. The partial and full density of states were calculated, and used to examine differences between the surface and bulk. An Aluminum vacancy was also created on the surface, and calculations were run on this. The energy of the surface was found to be higher(less negative) than bulk, as expected, and changed from a strong insulator of band gap 5.9488 eV to a conductor. The calculations in this report will show that Al2O3 is highly ionic, an insulator in bulk, a conductor at the surface. Introduction: Alumina is highly important in many fields of electronics and engineering. It is an insulator, chemically non-reactive, and has a high melting point. Ruby, which is Alumina with a Cr3+ impurity, is the earliest and most well known laser crystal. Alumina is used in circuit and computer components, as well as micro-abrasives. The α-Al2O3 unit cell has a hexagonal cell structure, with a rhombehedral primitive cell consisting of 10 atoms. Four of these atoms are Aluminum, six are Oxygen. In this examination, a cell of 60 atoms was created, cleaved at the (ī10), using the Cleave Surface tool in Materials Studio. A 60 atom cell was chosen so that there would be little interaction between the surfaces. The cell used has a u-vector, which spans the distance from the origin to the point A, with length 5.13 Ǻ. The cell is also defined by a v-vector, which is from the origin to the point B, its length is 6.99 Ǻ. The vectors u and v are separated by an angle γ = 84.16˚. Both u and v are perpendicular to the vector w. The last vector necessary to describe the cell dimensions is the w-vector, which is from the origin to the point C. Fig. XXXX: Rhombohedral primitive cell. Lattice dimensions of a1=a2=a3= 5.128 Ǻ α=γ=β=55.28˚ After cleaving the plane, a vacuum slab of thickness 10 Angstroms was added. The cut and vacuum slab are made precisely such that there is consistent pattern, i.e. ABCDABCDABC (cleavage) DABCD. The surface is Aluminum terminated, the last layer having four Al atoms. K-point and Energy Cut-off convergence tests were done to find optimum settings. When relaxing a surface, atoms nearer to the surfaces are expected to relax with greater displacements than those atoms located in the inside of the cell. This is due to the fact that there are no longer atoms providing electrons to the outer atoms, in order for these outer atoms to feel that there shells are being completed, they sink down into the still "complete" cell. Of course, since there are only discontinuities along the w-direction, relaxations should be chiefly in this direction. U and V direction displacements are very slight. For the (000) surface of Alumina, such behavior was indeed observed. The Aluminum atoms have the greatest relaxations, as they are able to sink downwards into triangle formations of Oxygen atoms below them. Near to the surface, large displacements occur, while in the center of the cell, displacements are so small that the atomic positions those of bulk Alumina. For the (ī10) plane, relaxations similar to this are not expected, as there are no "convenient" resting spots for the Aluminum atoms to take. The structures have all been tilted; there are no triangle formations of Oxygen for the Aluminum atoms to sink into along the w-direction. Results actually show that there are significant relaxations all along the cell length, in not only the wdirection, but in the u and v as well. 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 Fig XXXX: Percent relaxations for Alumina in the u-direction. Notice that the greatest displacements are near to the surfaces. Inside the cell, near to the middle, there is very little relaxation, with the structure being almost bulk. Before Relaxation After Relaxation Fig XXXX: Atomic Positions before and after relaxation, notice the showcased atoms have moved the greatest. 15 10 5 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 -5 -10 -15 Fig. XXXX: Percent relaxation in Alumina in v-direction. Notice that relaxations near to the surface are greatest. The small relaxations in the center are more apparent here. Before Relaxation After Relaxation Fig. XXXX: Atomic positions after relaxation. Notice the two atoms showcased have moved the greatest. 1 0.5 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 -0.5 -1 -1.5 Fig. XXXX: A graph of the percent relaxation in Alumina along the w-direction. These relaxations are mostly small, with only slightly larger relaxations near to the surface. Before Relaxation After Relaxation Fig XXXX: Atomic Positions before and after relaxation, notice that there are very little displacements along the w-direction. The energies of the bulk, un-relaxed, and relaxed cells are: Energy (eV) E/Atom Bulk Un-relaxed Relaxed -2876.0202 -287.6020 -17223.4408 -287.0573 -17229.7369 -287.1622 In these calculations, 2 k-points were used. Cut off energy was 300 eV. After finding the energies of the bulk and surface, the surface formation energy can be calculated. The surface formation energy is the energy required to create the surface. The surface energy is the change in energy from bulk to the surface divided by the area of each surface. The energy at the surface (SE) can be calculated thus: SE = (Esurface - N*(Ebulk/n))/(2*A) where N is the number of atoms in the Surface cell, n is the number of atoms in the bulk cell, and A is the area of the surface. The surface area for this system can be found in this manner: (uXv) = |u|*|v| * sin(θ) A = (5.13 Ǻ)*(6.99 Ǻ)*sin(84.16˚) A = 35.67 Ǻ2 The calculated surface formation energy for Alumina is: SE = ((-17223.4408 eV) – 60*(-2876.02028 eV/10 atoms))/(2*35.67 Ǻ2) SE = 0.458 eV/ Ǻ2 = 7.328 J/m2 In comparison with other metal oxide surfaces, this surface energy is quite large. A published surface energy for the (000) surface is 3.5678 eV/ Ǻ2. We can now calculate the surface energy for the relaxed surface. SE = ((-17229.7369 eV) – 60*(-2876.02028 eV/10 atoms))/(2*35.67 Ǻ2) SE = .369 eV/Ǻ2 = 5.904 J/m2 5.904 J/m2 is closer to previous results for a similar surface. The density of states for bulk Alumina shows that it is plainly a very strong insulator, with a very wide band gap. Most of the valence electrons near the Fermi energy are in the P states, while most of the states in lower energies in S states. The states past the Fermi energy consist of a more equal mix of s and p states, with d states not present. After cleaving the surface, adding the vacuum slab, and relaxing the surface, the density of states can be run for the surface. In comparison with the bulk density of states, it can be seen that the surface is actually a conductor. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 -25 -20 -15 -10 -5 0 s 5 p 10 15 20 d Fig. XXXX: Density of states for bulk Alumina. Notice that states from -20 to -15 are chiefly s states, while states from -10 to 5 are chiefly p states. States outside the Fermi energy are more balanced between s and p, although not filled at zero degrees. 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 -30 -20 -10 s p 0 10 d Fig. XXXX: Density of states for Alumina relaxed surface. Notice that there is now no Fermi gap, this system has become a conductor. The lower energies are still mostly s states, and the higher energies are still mostly p states. Now that the examination of the bulk and surface energies and density of states is completed, we can look at the charge density for our systems. The charge density analysis option shows how the charge is distributed inside the cell. For a highly ionic system, charge will be localized at certain elements. This means that these particular elements have more electron negativity, and will attract the free electrons from the other elements. In an ionic system, these free electrons are drawn completely to the other attractive elements. Fig XXXX: Charge density along two different planes in the Alumina bulk primitive cell. Notice that all charge is localized about the red Oxygen atoms. Oxygen is a highly electro-negative, and so makes the bonds of this system ionic. Aluminum Terminated Oxygen Terminated Fig XXXX: Charge density at the two surfaces, notice that the Aluminum terminated surface has only small amounts of charge, due to the Oxygen atoms immediately below the surface. The Oxygen terminated surface shows high charge around the O atoms. These figures show that there is no change in the behavior of charge between the bulk and surface charge densities. There is still strong charge localization about the highly ionic Oxygen atoms, and still strong charge de-localizations about the Aluminum atoms. Such behavior, again, is the sign of ionic bonds, and an ionic system. The absence of charge at the upper surface and collection of charge at the lower surface may bring rise to an electric field, although this effect has not been studied in this report. Conclusions: As can be seen from this report, Alumina is indeed an insulator that changes into a conductor at the (ī10) surface. It has strong ionic bonds, with charge localized at the Oxygen atoms. The high surface energy suggests that this surface is difficult to create, and may fall apart quickly. Future Work: After having completed an analysis of the (ī10) surface in Alumina, the next step is to discover whether or not a vacancy at the surface can be made more easily than at the (001) plane. Such behavior can be seen in some other metal-oxides. Another interesting project would be to see if adding a magnetic atom in the system such as Cobalt or Iron can change the magnetic moment of the entire system.