The contributions of learning in the arts to educational, social, and

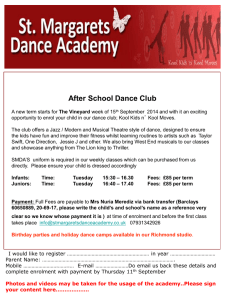

advertisement