Stratery #1 Engaging student in a new topic

advertisement

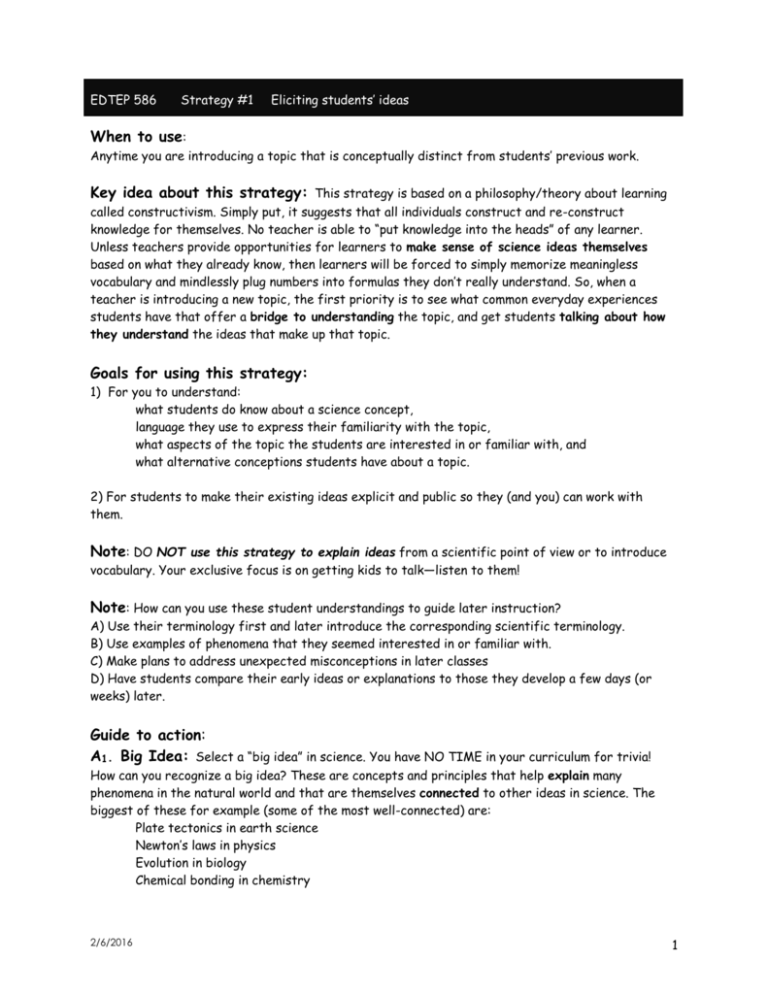

EDTEP 586 Strategy #1 Eliciting students’ ideas When to use: Anytime you are introducing a topic that is conceptually distinct from students’ previous work. Key idea about this strategy: This strategy is based on a philosophy/theory about learning called constructivism. Simply put, it suggests that all individuals construct and re-construct knowledge for themselves. No teacher is able to “put knowledge into the heads” of any learner. Unless teachers provide opportunities for learners to make sense of science ideas themselves based on what they already know, then learners will be forced to simply memorize meaningless vocabulary and mindlessly plug numbers into formulas they don’t really understand. So, when a teacher is introducing a new topic, the first priority is to see what common everyday experiences students have that offer a bridge to understanding the topic, and get students talking about how they understand the ideas that make up that topic. Goals for using this strategy: 1) For you to understand: what students do know about a science concept, language they use to express their familiarity with the topic, what aspects of the topic the students are interested in or familiar with, and what alternative conceptions students have about a topic. 2) For students to make their existing ideas explicit and public so they (and you) can work with them. Note: DO NOT use this strategy to explain ideas from a scientific point of view or to introduce vocabulary. Your exclusive focus is on getting kids to talk—listen to them! Note: How can you use these student understandings to guide later instruction? A) Use their terminology first and later introduce the corresponding scientific terminology. B) Use examples of phenomena that they seemed interested in or familiar with. C) Make plans to address unexpected misconceptions in later classes D) Have students compare their early ideas or explanations to those they develop a few days (or weeks) later. Guide to action: A1. Big Idea: Select a “big idea” in science. You have NO TIME in your curriculum for trivia! How can you recognize a big idea? These are concepts and principles that help explain many phenomena in the natural world and that are themselves connected to other ideas in science. The biggest of these for example (some of the most well-connected) are: Plate tectonics in earth science Newton’s laws in physics Evolution in biology Chemical bonding in chemistry 2/6/2016 1 There are, of course, many important ideas that are small parts of the big ideas mentioned above. You may want to choose a more focused idea rather than some of the grand theories listed above. Another way to identify big ideas is to look up standards from documents such as the Essential Academic Learning Requirements of Washington, the National Science Education Standards, or the Atlas of Scientific Literacy. Important note: When thinking of a big idea, do not select a THING (like “plants” or “layers of the earth”). Especially for your microteaching experience, stay away from microscopic, abstract things like cells and atoms. Rather, select DYNAMIC PHENOMENA like photosynthesis, genetic inheritance, pendulum motion, plate tectonics, or chemical change. These are much more compelling to learn and require understanding of relationships and mechanisms in addition to knowing vocabulary. HOWEVER students will have a difficult time talking about scientific molecular processeshypothesizing how photosynthesis works or how inheritance works are science ways of thinking that target specific content rather than student thinking about larger principles. Having students talk about photosynthesis or inheritance would be better suited for strategy 3 (interactive concept building). Sample questions that work well: Diagram all of the products that go into making a hamburger. Sample questions that do not work well: Why is the sky blue? How does your heart work? A2. Approach: Find a way to approach your topic from existing ideas and experiences that your students are likely to have. By “connect” I do not mean that you simply ask students “Have you ever heard of photosynthesis?” (or “momentum” or “acids and bases”). Rather, think of real life experiences that your students are familiar with and think of open-ended questions about those experiences. Instead of asking about photosynthesis, ask about plants growing in a terrarium, instead of asking about momentum, ask about a roller coaster, instead of asking about acids ask about car batteries or common household products. Important notes: All students, despite their backgrounds should have reasonable expectation to engage in discourse about your question/task, i.e. it relates to their out of school experiences. o Your question/task should have multiple plausible answers that encourage student discussion. o You are not fishing for a “right answer.” Use some kind of “prop” or activity. One way to get students talking (which is what you want) is to generate a sense of “puzzlement” by giving an example of the topic/concept and posing questions about it. This is particularly helpful if your students do not have shared experiences to draw on. This can be done with a: - teacher-led demo - image - brief demo that students can do - interesting artifact - provocative question about a current event - pictorial riddle - story - combinations of the above - video clip 2/6/2016 2 A3. Questions: What kinds of questions can you ask? (Don’t forget, your goal is to engage students in a conversation, not to lecture or quiz!) Observations only: ask “safe” questions in which every student can likely contribute without being right or wrong. For example, if you are studying plate tectonics, ask students where they were during the recent earthquake and what they felt (personal experience questions). Another example is to do a demonstration of pendulum motion and ask “what do you see happening as I shorten the string?” Try not to let individual students explain phenomena in detail, it preempts efforts to understand by others. Hypothesizing next, you will try to get a sense of student thinking—to make it public through dialogue, writing, or drawing. You ask “riskier” questions such as “what-ifs?” (predictions). For example, “What would happen if we swung the pendulum from a greater height?” or “What would happen if all the coyotes in this ecosystem were eradicated?” Through experience, you will develop a skill for follow-up questions such as “Can you tell me what you mean by ….?” Or “How is that related to what your classmate said earlier?” Don’t depend only on questions such as “Have you ever heard of…?” By themselves, these types of questions tell you very little. (Side note: closely monitor your own use of language—don’t use terms students aren’t familiar with early in the lesson.) What are other ways in addition to class dialogue that you can get a sense of students’ preconceptions? - have students draw representations of the concept/topic in the form of concept maps, diagrams, art works, or flow charts, etc. - have students offer interpretations of graphs, images, drawings Treat all experiences by your students as valid, respectable interpretations of the world. Treat all comments and initial hypotheses with respect. B. Sometime during the course of this introductory lesson tell students what the topic of study is and help students understand why the topic is important. C. After this conversation with students, summarize and record the ideas that have been elicited from students and move into next phase of instruction, taking into consideration what students find interesting and their level of understanding of the topic. The next phases of instruction (which we will explore later in our methods class) might include: - guided exploration (Strategy #2) - interactive concept development (Strategy #3) - building students’ skills (e.g. how to interpret a graph, do a titration, analyze data) - a field trip - inviting a guest speaker in - reading key material - others... 2/6/2016 3 Questions to ask yourself as you are developing your 10 minute segment of a lesson… What am I eliciting responses about? o A complex scientific model (this can be problematic) o An underlying theme important to science or the nature of science o Students experiences with a concept/ underlying theme important to science o Students’ explanations of the underlying concepts sparked from a discrepant event (an demonstration that causes wonderment) In what way am I eliciting student’s responses? o Teacher leads discussion asking questions that can be answered in a few words o Teacher leads discussion asking open-ended questions and probes for in depth responses from students (follow-up questions) o Teacher leads discussion asking open-ended questions, probing for details about students’ ideas & encourages students to respond to one another’s ideas o Teacher initiates small group discussions in which students share ideas with each other and then discuss their ideas with a larger group o Teacher provides a discrepant event and encourages students to discuss their thinking about the event (without walking the student through the teachers’, or scientific, way of thinking). Other o o o o Questions How much time am I planning on talking? How much time were my students talking/drawing? Can I describe how individual students in my class understand this concept? Do I have a sense for the kind of words they would use to describe this concept? Can my students repeat back to me, why this topic is important or what they might be learning in the future? o What were my students doing most of the time? Listening? Dialoguing with the teacher? Group discussion? Drawing? Making inferences? 2/6/2016 4 Peer Comments on the Eliciting Ideas Strategy Following are valuable reflections from last year’s students… Go with it. When I taught the lesson I was surprised at how many the students answers differed from the natural order I thought the discussion would take. I found myself leading the discussion based on the responses I receive instead of strictly following the lesson outline. The biggest challenge was when I tried to get certain student responses—it is hard to keep students on track when you are not trying to teach them anything but just try to find out what they know. Simplicity counts. Keeping a concept simple is very important. Rather than assume that students have a background in a subject, next time I will start with the most basic concepts in a subject. Avoid definitions. I wish I had not introduced vocabulary. I unfortunately taught them new concepts instead of using the teaching activity to only bring out their ideas. It is hard to elicit ideas from your students if you are using definitions and ideas not yet covered. Students really do zone out if the lesson is boring. If students have not been engaged they still have the ability to parrot what the teacher has taught, however, this is a vastly different level of understanding from what occurs when there is active participation from the students. Try to use everyday language as much as possible. Focus on student meaning. I was surprised at how difficult it was to capture my students’ meaning without adding meaning. I need to ask the students to justify their answers. Make it personal. Elicit ideas that get students thinking about themselves and make the topic personal. It would be good to relate challenging problems to personal experience and their home life. Asking students to relate an idea to a personal experience is what can get at the student’s previous knowledge, which we are trying to understand. If I could redo this lesson I would incorporate more human information, to make it more accessible to my students. Wait time. Give students some time to think, some people take longer to process than others. I had to concentrate on not filling the silent space. Talking slow give students time to think. The 7 second rule of waiting after a question would be useful. Probing. It’s important to not give up too soon on a line of questioning. Ask more opinion questions: “Why do you think that?” Students will be more willing to share— everyone has an opinion. My questions were a bit too leading; I need to change them to make them more open-ended. Use examples. If I were to teach the lesson again, I think I would give each student interesting examples as food for thought. Having tangibles in your lesson can really help students think. Passing out pictures can really help a brainstorm. Add student representations & use the board. If I were to repeat this lesson I would write ideas down anon the board as they were brought up in class. Then, the class and I could refer back to earlier concepts. Also, I would draw the demo set-up on the board, it would be easier for the students to keep track of what is happening in the system and it would 2/6/2016 5 tap into the visual learning process as well. Keep visual displays simple. I should have students draw rather than simply showing them my picture. Terminology Be prepared. I really need to OVERprepare for this type of teaching so that I can be ready for almost any answers. I was amazed at how little I really knew about the concept because I had never thought about it other than in terms it was presented to me. Be explicit about objectives. It will help me to make explicit the goals of the lesson, before and after the lesson. 2/6/2016 6