Mgr. Jana Obrovská , Faculty of Social Studies, Department of

advertisement

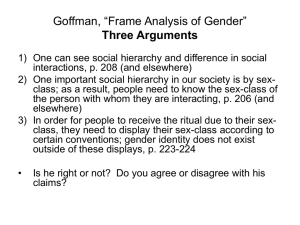

Mgr. Jana Obrovská, Faculty of Social Studies, Department of Sociology, Masaryk University, Brno, 7.10. 2013 Research Proposal Research Topic: Interaction Rituals in Ethnically Diverse Classroom: Ethnography of CzechRoma Pupil Community (her you need to choose the singular or plural. If you use the singular, you need to write ‘an ethnically diverse classroom’; if plural, write ‘in ethnically diverse classrooms’ Research Problem: In the year 2007, the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg declared that the Czech Republic had discriminated against the groups of minority Roma pupils by categorizing them as mentally handicapped and puting placing them to in special vocational - so called ‘practical’ - schools. These schools with thier restricted curriculum provided a lower less quality education and so the educational gap between Roma and majority children became an issue. Although in public discourse there are stengthening initiatives to discuss the relationship between the educational segregation of Roma children and the reproduction of their low socio-economic status, there is still a widespread unwillingness of by majority parents and many teachers, to educate majority children together with Roma. After Five years After of the Strassbourg court verdict, Roma segregation remains a widespread practice (Human Rights Council 2012) and the public image of Roma is even worse than it was previously; there were about fifteen anti-Roma marches in Czech cities at the end of August 2013, initiated by extreme right wing followers. Despite criticism by the international institutions and non-governmental organizations critics, high selectivity and segregating mechanisms seem continue to be strongly embedded and endured in the Czech educational system. However, there are some mainstream, non-segregated public schools integrating Roma children into mixed classrooms with majority pupils. My study is designed as focuses on the ethnography of a classroom at a choosen school in a Czech medium-sized Czech border town, which is attended by both Roma minority as well as and majority pupils. The Current state of knowledge in the field of Roma education, is largely focused on those external factors that influence the unsatisfying (or unsatisfactory?) short Roma educational careers of Roma pupils. Many researchers aim at focus on the social and spatial exclusion of Roma populations and its impact on inter-cultural relationships (Marada, Nekorjak, Souralová, Vomastková 2010, Bittnerová, Doubek, Levínská 2011) or on the nature of Roma family socialization and its influence on education (Němec 2009). In the Czech context, as well as in other countries, research there is the obvious places emphasis on the structural and familial factors of ethnic minority education (Connolly 2002, D’Amato 1996). It is important to look at the relational dynamics of ethnically diverse classrooms because the lived experience of pupils is crucial for their further educational careers. Mgr. Jana Obrovská, Faculty of Social Studies, Department of Sociology, Masaryk University, Brno, 7.10. 2013 Research subject: The education of ethnic minority pupils is predominantly researched within the a framework of cultural or social reproduction theories (Bourdieu, Passeron 1990). These perspectives strongly established in the field of sociology of education, result in the main focus being on reproduction of social inenqualities and the forms of their maintenance in a school’s institutional cultures. My interest in the social dynamics of a particular classroom, leads me to take a use much more micro-social perspective, which then enables me to capture the more subtle, situational reality of how pupils interact in the classroom interactions. My research is framed by the symbolic-interactionism paradigm, which is suitable for the when analysing of the ways in which pupils’ identities and relationships are constructed and culturally produced. It considers the actor as able to bring new symbols into interactions (Blumer 1969) and so opens the possibility of social change in classroom relations. It also helps to question the idea of stable and coherent ethnicity as determining structural category; and more importantly, it invites the researcher to see the classroom collectivity as a distinct group of children with its own moral and cultural systems. To summaris, up it offers the researcher an alternative to prevailing cultural deficit theories and reproductionist theories of education. Specifically, I intend to will use the interaction ritual perspective to explore the non-rational aspects of education in an ethnically mixed classroom. I consider the ritual to be part of school expressive culture (Bernstein, Elvin, Peres 1966) and the hidden curriculum of education. I presuppose that rituals can play an important role in mutual relationships between pupils and between pupils and teachers. I expect that the selfevident nature of rituals can be threatend in a multicultural environment. However in the educational ethnography, ritual did not become an important aspect of the social and cultural analysis of education (Quantz 1999) despite the expanding knowledge of rituals in the interdisciplinary field of ‘ritology’ (Bell 1992). Nonetheless, the ritual dimension of education is an important one because, as Quantz and Magolda (1997) state: when the nonrational rituals of school ignore or contradict a child's own identity and commitments, we should not expect much learning to occur. Wulf (in Šeďová, Švaříček 2012) elaborates further on the institutional significance of rituals by claiming that, without the change of rituals, no educational reform can be successfully implemented. Theoretical background: The Classic sociological theorists predicated a strong affinity between modernity and increasing rationalization. Max Weber (1997, 2009) expected a ‘disenchanted’ character of the secularizing world, which is experienced without mystery and belief. However, in recent decades (years? Ecades doesn’t sound right here – you could say, ‘over the last (x amount) of decades….), an increasing number of scholars have come to doubt the self-evident relationship constructed between premodern irrationality and modern rationality. According to Jenkins (2000) even in the life of big bureaucratic institutions (e.g. schools) we can find symbols, rituals, traditions and legends as important Mgr. Jana Obrovská, Faculty of Social Studies, Department of Sociology, Masaryk University, Brno, 7.10. 2013 irrational sources of experience. Unlike rituals in tribal societies, characterised by their strong integrative effects, rituals in modern complex societies are more performative and transient (Alexander, Giesen, Mast 2006). The study of everyday secular rituals in education seems to be quite an analytical challenge, because the more everyday they rituals are, the more invisible and covert they seem appear to be. Because I am interested in the subtle forms of ritualizations in the everyday life of ethnically diverse classroom, and therefore, I have choosen suitable sociological and anthropological theories of rituals suitable proper for the analysis of interaction rituals. Instead of gradually presenting the basic tenets of all of these, (these what? Rituals? Theories?) clarify…) I will introduce the interactionist analytical model based on choosen aspects and concepts involved in these theories. The interaction ritualist model presupposes that ritual can be enacted when there are two or more individuals in the physically present. They share cognitive and visual attention; respect is displayed to some socially valued object or symbol and this produces positive or negative emotions and feelings of solidarity with, or feelings of exclusion from, some existing (classroom) community (Goffman 1967, Collins 2004). The model is multidimensional, it captures emotionality, corporeality, conversational structure and produced or re-produced morality. Spatially, I would like to start my analysis with performative aspects of classroom events in the so called performance areas of classrooms where rituals usually take place, for example, the space in front of blackboard or the threshold between classroom and corridor etc.) (Wulf 2010). I will concentrate on nonverbal behaviour such as, repeating gestures or the facial expressions of the actors. It is methodologically challenging is to grasp shared emotional mood and produced moral sentiments. Emotional energy can expand from high levels of enthusiasm to the a lack of initiative and depression. Collins (2004) differentiates sociometrical stars situated in the ritual core, from ritual followers who lack initiative to act and who are situated on ritual fringes. Although during the everyday micro-rituals the intensity of emotional engagement is definitely lower than during the big large formal ones, for example, a certificate ceremony or a pop concert, we can observe the level of the rhythmic and physical harmonization of interaction partners, the intensity of laughter, joy, resistence or protest. Enthusiasm, as well as passivity as indicators of an actor’s emotional engagement, demonstrate themselves in the extent of each pupil’s popularity. Next to Alongside aesthetical and emotional situational features, I will analyze the ritual nature of speech – the ritualized beginnings and endings of the conversations, turn-taking rules, the intensity of rebukes and praise articulations (Goffman 1981). When considering the conversations, there is also a high level of importance is also placed on of rhythm, tone of voice, fluency, intensity of breaks or emergence of some strange noises. We can expect to observe different conversational styles with regard to the different cultural backgrounds of the pupils (Rawls 2000). In accordance with Goffman (1967) I will put also intend to place at the centre of my analysis the ways of displaying (dis)respect at the centre of my analysis. In Mgr. Jana Obrovská, Faculty of Social Studies, Department of Sociology, Masaryk University, Brno, 7.10. 2013 such situations there is the danger of ritual profanations such as ceremonial contempt (there could be inappropriate respect in play), playful profanation (making fun of somebody), interaction breaks or rituals of punishment (using gestures which are not in compliance with the normative rules, playing inadequate roles). I am also interested in the ways in which actors try to recover the lost ritual balance of the a situation – for example, by through humour, resistence or stigmatizing of the other individual. The actor who produces the situational ritual instability feels ashamed and is embarrassed, and this has many empirical manifestations which can be recognized - for example, stuttering, sweating, irresolution etc. In When analysing of embarrassment, it is important to ask: what categories of people are repeatedly embarrassed and in which recurrent situation is this happening? I will further focus on prevailing techniques of impression management in ritual events (Goffman 1999) because as less competent pupils will probably be probably more often ritually punished more often to recover the interaction order. Professor Wulf and his colleagues concentrate on the transitional phases of rituals where children leave one social status – for example, being a pupil, and transform it in to another, one for example, being a mate. During these liminal ritual phases (Turner 2004, 1982) we can observe the playful appeal, transformations and dramatizations of the existing symbolic meanings attached to particular social roles and statuses. During these processes, the existing communities are strengthen and new ones are emerge. Ritualizations set the boundaries which create different communities (according to the age of the pupils, their ethnicity or classroom affiliation) and perform and dramatize differences. (Göhlich, WagnerWilli 2007). This model can serve as an interpretative and analytical framework for ethnography of multicultural classrooms. I presuppose that ethnicity is a very important factor in the character of interaction rituals and it was has not been, until now, thoroughly properely studied. At the same time, I conceptualize the classroom as a space for identity negotiation and changes of ritualized forms of interactions. The differences in interaction styles can be equalized through the assimilating pressure of a dominant culture, or they can persist and produce some forms of resistence, stigmatizing processes and tensions, or there can be some kind of crossing over by producing the local interaction style and rules of conduct that dwell on specific local cultural structure of the classroom. Mgr. Jana Obrovská, Faculty of Social Studies, Department of Sociology, Masaryk University, Brno, 7.10. 2013 Research Questions: Are there differences between school institutional culture and classroom culture? Are there any subcultural forms of behaviour in between the classroom collectivity? What are the repetitive moral frames that guide the behaviour of pupils? Do the rituals contribute to the enhancment of classroom community? In what ways, and by which occurances is the respect ritually displayed in the classroom interactions? How do the pupils display the respect to the school institution? In what ways do they avoid the ritual confirmation of school order? What are the teachers’ reactions to ceremonial profanations? In what ways are the classroom interaction rituals stratified (along the axes of ethnicity, age, reputation)? Are there ruptures in the interaction order (what, when) in mutual pupils’ interactions? Does ethnicity play any role during the interactional breaks and incidents? Are the minority pupils stigmatized? How is the interaction order re-established? What kind of impression management is present in the classroom interactions? Methodology: Because of My aim is to study culture and interactional rituals in one classroom for over an extended longer period of time, therefore, it is not possible to unavoidable avoid to using ethnography as the main methodological approach to my research. Observations done in the classroom and corridors, as well as in toilets, are neccessary for micro-analysis of face to face interactions. To avoid the drawbacks of de-contextualized micro-social analysis, I will also reflect on possible pupils’ possible sub-cultural identities formed outside the school (Gordon, Holland, Lahelma 2007). Doing that I am inspired by the innovative techniques in the field of marginalized actors research, especially by so called ‘multisided ethnography’ (Dillabough, Kennelly 2010) conducted in many spaces, simultaneously. Ethnography is very fitting with regards to my research topic, as because in it enables the combination of many different data gathering techniques. Next to Alongside the more standardized techniques ones (participant observations, individual interviews, focus groups) I would like to use some projective techniques, socio-games or task-centerd activities (James 1998) which depict children’s fantasies, in possibly in new light. My study is designed as ethnography of one choosen classroom in a small town with proinclusive local policy. Although living mainly in socially excluded localities, Roma children have to attend schools in compliance with an established gradient system to achieve proportionality between schools. There is any (? – there are many?) segregated schools in the town and school directors lead (? need?) the system to have maximum of three to four Mgr. Jana Obrovská, Faculty of Social Studies, Department of Sociology, Masaryk University, Brno, 7.10. 2013 Roma children in each classroom. not make sense, so re-think it). (I am not sure what you want to say here, but it does State of my research project (re-think this – it has negative connotations. May be you could write ‘My research [project] to date) Until nowadays I have already conducted the ethnography of the town by summarizing the history of Roma migration, doing holding interviews with local politicians, mapping the history of establishing inclusive local policy, doing holding interviews with the directors of all schools in the town, with representatives of non-governmental organizations dealing with education, and also as well as with some Roma parents. In Over the next few months, I intend to will start with the ethnography of one classroom, which I want would like to visit regularly for the over a period of one year. After that Following this, I would like to conduct my scholarship in Berlin in order to have the opportunity to consult (as much as possible) the interpretation of my data and analytical proceedings. Because of that Therefore, I would consider it a great be really grateful to have the opportunity to stay in Berlin and work on my dissertation project with the help of Professor Wulf. Literature: Alexander, J., B. Giesen, J. L. Mast. 2006. Social performance : symbolic action, cultural pragmatics, and ritual. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bell, C. 1992. Ritual Theory Ritual Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Bernstein, B., Elvin, H. L., Peters, R. S. 1966. „Ritual in education“. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 251(772): 429-436. Bittnerová, D., Doubek, D., Levínská, M. 2011. Funkce kulturních modelů ve vzdělávání. Praha: Fakulta humanitních studií Univerzity Karlovy. Blumer, H. 1969. Symbolic interactionism. Perspective and method. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. Bourdieu, P., Passeron, J.-C. 1990. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. London: SAGE Publications. Connolly, P. 2002. Racism, Gender Identites and Young Children. Social Relations in Multi-Ethnic, Inner City Primary School. London: Routledge. Collins, R. 2004. Interaction Ritual Chains. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. D’Amato, J. 1996. „Resistance and Compliance in Minority Classrooms.“ In Jacob, E. Jordan, C. (eds.). Minority Education. Anthropological Perspectives. Norwood: Alex Publishing Corporation. Dillabough, J. A., Kennelly, J. 2010. Lost Youth in the Global City. Class, Culture and the Urban Imaginery. New York: Routledge. Mgr. Jana Obrovská, Faculty of Social Studies, Department of Sociology, Masaryk University, Brno, 7.10. 2013 Goffman, E. 1999. Všichni hrajeme divadlo. Sebeprezentace v každodenním životě. Praha: Nakladatelství Studia Ypsilon. Goffman, E. 1981. Forms of Talk. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Goffman, E. 1967. Interaction rituals : essays on face to face behaviour. New York: Anchor books doubleday & company. Göhlich, M., Wagner-Willi, M. 2007. „School as a ritual institution.“ Pedagogy, Culture & Society 9 (2): 237-248. Gordon, T., Holland, J., Lahelma, E. 2007. „Ethnographic Research i Educational Settings.“ In Atkinson, P. (ed.). Handbook of Ethnography. London: SAGE Publications. Human Rights Council. 2012. Submission: Universal Periodic Review: Czech Republic. Poskytnuto Open Society Fund. Jenkins, R. 2000. „Disenchantment, Enchantment and Re-Enchantment: Max Weber at the Millennium“. Max Weber Studies 1: 11-32. Quantz, R. A. 1999. „School Ritual as Performance: A reconstruction of Durkheim’s and Turner’s uses of ritual.“ Educational Theory 49 (4): 493-513. Quantz, R. A., Magolda, P., M. 1997. „Nonrational Classroom Performance: Ritual as an Aspect of Action“. The Urban Review 29 (4): 221-238. Marada, R., Nekorjak, M., Souralová, A., Vomastková, K. 2010. EDUMIGROM: Community Study Report: Czech Republic. Brno: Masarykova univerzita. Němec, J. 2009. „Sociální a kulturní determinanty a strategie edukace romských žáků.“ Orbis Scholae, 3 (1): 99-120. Rawls, A. W. 2000. "Race" as an Interaction Order Phenomenon: W.E.B. Du Bois's "Double Consciousness" Thesis Revisited“. Sociological Theory 18 (2): 241-274. Šeďová, K., Švaříček, R. 2012. „Forgotten values and dreams of Education: An Interview with Christoph Wulf.“ Studia paedagogica 17 (2): 109-116. Turner, V. 2004. Průběh rituálu. Brno: Computer Press. Turner, V. 1982. From Ritual to Theater. The Human Seriousness of Play. New York: PAJ Publications. Weber, M. 2009. „Věda jako povolání“. Pp. 108-132 in Havelka, M. (ed.) Metodologie, sociologie a politika. Praha: OIKOYMENH. Weber, M. 1997. „Protestantská etika a duch kapitalismu“. Škoda, J. (ed.) Autorita, etika a společnost. Praha: Mladá fronta. Wulf, Ch. 2010. Ritual and Identity. The Staging and Performing of Rituals in the Lives of Young People. London: Tuffnel. Mgr. Jana Obrovská, Faculty of Social Studies, Department of Sociology, Masaryk University, Brno, 7.10. 2013 Mgr. Jana Obrovská, Faculty of Social Studies, Department of Sociology, Masaryk University, Brno, 7.10. 2013 Jana, a few things to consider: 1. Your use of articles – you need to revise how these are used. There ar lots of useful websites on the internet to help with this; here are a few that you might find useful: http://learnenglish.britishcouncil.org/en/english-grammar/determiners-andquantifiers/indefinite-article-and http://learnenglish.britishcouncil.org/en/english-grammar/determiners-andquantifiers/definite-article 2. The use of punctuation is different in each language and so it is with English and Czech. Your use of the comma in English needs revising – you don’t use it when necessary and this causes your writing to adopt a ‘rambling’ tone rather than the needed precision and clarity. It is very difficult for the reader to then decipher exactly what is being said. Lack of correct punctuation (commas) can actually make a sentence incoherent, so here’s a website that might help you understand its use better: http://www.whitesmoke.com/uses-of-commas http://grammar.ccc.commnet.edu/grammar/commas.htm 3. Try not to use ‘because’ at the beginning of a sentence – it is not incorrect to do so, but in this context, it is simply too informal. Alos, try to substitute ‘because’ for ‘as’ (see corrections in text) as, again, this gives the text a more formal feel. 4. Word order – look at the corrections in the text. Ensure that you have things like adjectives and nouns the right way round and that adverbs are in the correct place in a sentence. If you put the adverb at the end of the sentence, you need to use a comma to separate it, for example - I would like to concentrate on x theory, specifically. 5. Parts of speech – double check that you have the right part of speech, for example: Facial (adjective) expression (noun) and not, face (noun) expression (noun) as you can’t describe a noun to describe a noun. Mgr. Jana Obrovská, Faculty of Social Studies, Department of Sociology, Masaryk University, Brno, 7.10. 2013 6. Use of the saxon genitive (or ‘s/s’) – substituting ‘of’ When you are using singular nouns the apostrophe comes before the ‘s’ – for example: The book of Jana becomes Jana’s book. The chairs of the pupils becomes the pupils’ chairs. If you use a person’s name and it ends with an ‘s’, then you put the apostrophe at the end, for example: The pen of James becomes James’ pen Note: James isn’t plural, it’s just that we don’t write James’s in English.

![afl_mat[1]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005387843_1-8371eaaba182de7da429cb4369cd28fc-300x300.png)