General anaesthesia Definition General anaesthesia (or general

advertisement

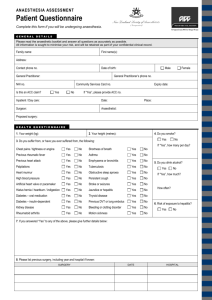

General anaesthesia Definition General anaesthesia (or general anesthesia) is a state of unconsciousness and loss of protective reflexes resulting from the administration of one or more general anaesthetic agents. A variety of medications may be administered, with the overall aim of ensuring hypnosis, amnesia, analgesia, relaxation of skeletal muscles, and loss of control of reflexes of the autonomic nervous system. The optimal combination of these agents for any given patient and procedure is typically selected by an anaesthesiologist or another provider such as a nurse anaesthetist, in consultation with the patient and the medical or dental practitioner who is performing the operative procedure. Biochemical mechanism of action The biochemical mechanism of action of general anaesthetics is not yet well understood. To induce unconsciousness, anaesthetics affect the GABA and NMDA systems. For example, halothane is a GABA agonist and ketamine is an NMDA receptor antagonist Preanaesthetic evaluation Prior to planned operation or procedure, the anaesthetist reviews the medical record and/or interviews the patient to determine the best combination of drugs and dosages and the degree to which monitoring will be required to ensure a safe and effective procedure. Key factors of this evaluation are the patient's age, body mass index, medical and surgical history, current medications, and fasting time. Thorough and accurate answering of the questions is important so that the anaesthetist can select the proper anaesthetic drugs and procedures. For example, a patient who consumes significant quantities of alcohol or illicit drugs could be undermedicated if s/he fails to disclose this fact. This in turn could then lead to anaesthesia awareness or dangerously high blood pressureCommonly used medications (e.g., sildenafil) can interact with anaesthesia drugs; failure to disclose such usage can also increase the risk to the patient An important aspect of the preanaesthetic evaluation is that of the patient's airway, involving inspection of the mouth opening and visualisation of the soft tissues of the pharynx. The condition of teeth and location of dental crowns and caps are checked, neck flexibility and head extension observed. If a tracheal tube is indicated and airway management is deemed difficult, then alternative methods of tracheal intubation, such as fibreoptic intubation, may be required as part of the anaesthetic management. Premedication Anaesthesiologists may prescribe or administer a premedication prior to administration of a general anaesthetic. Anaesthetic premedication consists of a drug or combination of drugs that serve to complement or otherwise improve the quality of the anaesthetic. One example of this is the preoperative administration of clonidine, an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist. Clonidine premedication reduces the need for anaesthetic induction agents, as well as the need for volatile anaesthetic agents during maintenance of general anaesthesiaand the need for postoperative analgesicsClonidine premedication also reduces postoperative shivering, postoperative nausea and vomiting and emergence deliriumIn children, clonidine premedication is at least as effective as benzodiazepines, in addition to having a more favourable side effect profileIt also reduces the incidence of post-operative delirium associated with sevoflurane anaesthesiaAs a result clonidine has become a popular agent for anaesthetic premedication Drawbacks of oral clonidine include the fact that it can take up to 45 minutes to take full effect hypotension and bradycardia Midazolam, a benzodiazepine characterized by a rapid onset and short duration relative to other benzodiazepines, is effective in reducing preoperative anxiety, including separation anxiety associated with separation of children from their parents and induction of anaesthesia Dexmedetomidine and certain atypical antipsychotic agents are other drugs which are used particularly in very uncooperative children. Melatonin has been found to be effective as an anaesthetic premedication in both adults and children due to its hypnotic, anxiolytic, sedative, antinociceptive and anticonvulsant properties. Unlike midazolam, melatonin does not impair psychomotor skills or adversely effect the quality of recovery. Recovery is more rapid after melatonin premedication than with midazolam, and there is also a reduced incidence of post-operative agitation and delirium. Melatonin premedication also reduces the required induction dose of propofol and thiopental. Another example of anaesthetic premedication is the preoperative administration of beta adrenergic antagonists to reduce the incidence of postoperative hypertension, cardiac dysrhythmia or myocardial infarctionOne may choose to administer an antiemetic agent such as droperidol or dexamethasone to reduce the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomitingor subcutaneous heparin or enoxaparin to reduce the incidence of deep vein thrombosis Other commonly used premedication agents include opioids such as fentanyl or sufentanil, gastrokinetic agents such as metoclopramide, and histamine antagonists such as famotidine. Non-pharmacologic preanaesthetic interventions include playing relaxing music, massage, and reducing ambient light and noise levels in order to maintain the sleep-wake cycle. These techniques are particularly useful for paediatric and mentally retarded patients. Other options for children who refuse or cannot tolerate pharmacologic premedication include interventions by clowns and child life specialists. Minimizing sensory stimulation or distraction by video games may also help to reduce anxiety prior to or during induction of general anaesthesia Stages of anaesthesia The four stages of anaesthesia were described in 1937. Despite newer anaesthetic agents and delivery techniques, which have led to more rapid onset and recovery from anaesthesia, with greater safety margins, the principles remain. Stage 1: Stage 1 anaesthesia, also known as the "induction", is the period between the initial administration of the induction agents and loss of consciousness. During this stage, the patient progresses from analgesia without amnesia to analgesia with amnesia. Patients can carry on a conversation at this time. Stage 2: Stage 2 anaesthesia, also known as the "excitement stage", is the period following loss of consciousness and marked by excited and delirious activity. During this stage, respirations and heart rate may become irregular. In addition, there may be uncontrolled movements, vomiting, breath holding, and pupillary dilation. Since the combination of spastic movements, vomiting, and irregular respirations may lead to airway compromise, rapidly acting drugs are used to minimize time in this stage and reach stage 3 as fast as possible. Stage 3: Stage 3, "surgical anaesthesia". During this stage, the skeletal muscles relax, and the patient's breathing becomes regular. Eye movements slow, then stop, and surgery can begin. It has been divided into 4 planes: 1. eyes initially rolling, then becoming fixed 2. loss of corneal and laryngeal reflexes 3. pupils dilate and loss of light reflex 4. intercostal paralysis, shallow abdominal respiration, dilated pupils Stage 4: Stage 4 anaesthesia, also known as "overdose", is the stage where too much medication has been given relative to the amount of surgical stimulation and the patient has severe brain stem or medullary depression. This results in a cessation of respiration and potential cardiovascular collapse. This stage is lethal without cardiovascular and respiratory support. This can be fatal. Induction Induction of general anaesthesia is usually conducted in a medical facility, most commonly in an operating room. However, general anaesthesia may also be conducted in many other locations, such as an endoscopy suite, radiology or cardiology department, emergency department, ambulance, or at the site of a disaster where extrication of the patient may be impossible or impractical. Anaesthetic agents may be administered by various routes, including inhalation, injection (intravenous, intramuscular or subcutaneous), oral, and rectal. After administration by one or more of these routes, the agents gain access to the blood. Once in the circulatory system, they are transported to their biochemical sites of action in the central and autonomic nervous systems, where they exert their pharmacologic effects. Most general anaesthetics today are induced either by intravenous injection or breathing a volatile anaesthetic through an anaesthetic circuit (inhalational induction). Onset of anaesthesia is faster with intravenous injection than with inhalation, taking about 10–20 seconds to induce total unconsciousness.[ This has the advantage of avoiding the excitatory phase of anaesthesia (see below), and thus reduces complications related to induction of anaesthesiaCommonly used intravenous induction agents include propofol, sodium thiopental, etomidate, and ketamine. An inhalational induction may be chosen by the anaesthesiologist where intravenous access is difficult to obtain, where difficulty maintaining the airway is anticipated, or due to patient preference (e.g. children). Sevoflurane is currently the most commonly used agent for inhalational induction, because it is less irritating to the tracheobronchial tree than other volatile anaesthetic agents Physiologic monitoring Monitoring involves the use of several technologies to allow for a controlled induction of, maintenance of and emergence from general anaesthesia. 1. Continuous Electrocardiography (ECG): The placement of electrodes which monitor heart rate and rhythm. This may also help the anaesthetist to identify early signs of heart ischaemia. 2. Continuous pulse oximetry (SpO2): The placement of this device (usually on one of the fingers) allows for early detection of a fall in a patient's haemoglobin saturation with oxygen (hypoxaemia). 3. Blood Pressure Monitoring (NIBP or IBP): There are two methods of measuring the patient's blood pressure. The first, and most common, is called noninvasive blood pressure (NIBP) monitoring. This involves placing a blood pressure cuff around the patient's arm, forearm or leg. A blood pressure machine takes blood pressure readings at regular, preset intervals throughout the surgery. The second method is called invasive blood pressure (IBP) monitoring. This method is reserved for patients with significant heart or lung disease, the critically ill, major surgery such as cardiac or transplant surgery, or when large blood losses are expected. The invasive blood pressure monitoring technique involves placing a special type of plastic cannula in the patient's artery - usually at the wrist or in the groin. 4. Agent concentration measurement - Common anaesthetic machines have meters to measure the percent of inhalational anaesthetic agent used (e.g. sevoflurane, isoflurane, desflurane, halothane etc.). 5. Low oxygen alarm - Almost all circuits have a backup alarm in case the oxygen delivery to the patient becomes compromised. This warns if the fraction of inspired oxygen drops lower than room air (21%) and allows the anaesthetist to take immediate remedial action. 6. Circuit disconnect alarm - indicates failure of circuit to achieve a given pressure during mechanical ventilation. 7. Carbon dioxide measurement (capnography)measures the amount of carbon dioxide expired by the patient's lungs. It allows the anaesthetist to assess the adequacy of ventilation 8. Temperature measurement to discern hypothermia or fever, and to aid early detection of malignant hyperthermia. 9. EEG or other system to verify depth of anaesthesia may also be used. This reduces the likelihood that a patient will be mentally awake, although unable to move because of the paralytic agents. It also reduces the likelihood of a patient receiving significantly more amnesic drugs than actually necessary to do the job. Airway management With the loss of consciousness caused by general anaesthesia, there is loss of protective airway reflexes (such as coughing), loss of airway patency and sometimes loss of a regular breathing pattern due to the effect of anaesthetics, opioids, or muscle relaxants. To maintain an open airway and regulate breathing within acceptable parameters, some form of "breathing tube" is inserted in the airway after the patient is unconscious. To enable mechanical ventilation, an endotracheal tube is often used (intubation), although there are alternative devices such as face masks or laryngeal mask airways. Neuromuscular blockade "Paralysis" or temporary muscle relaxation with a neuromuscular blocker is an integral part of modern anaesthesia. The first drug used for this purpose was curare, introduced in the 1940s, which has now been superseded by drugs with fewer side effects and generally shorter duration of action. Muscle relaxation allows surgery within major body cavities, e.g. abdomen and thorax without the need for very deep anaesthesia, and is also used to facilitate endotracheal intubation. Acetylcholine, the natural neurotransmitter substance at the neuromuscular junction, causes muscles to contract when it is released from nerve endings. Muscle relaxants work by preventing acetylcholine from attaching to its receptor. Paralysis of the muscles of respiration, i.e. the diaphragm and intercostal muscles of the chest requires that some form of artificial respiration be implemented. As the muscles of the larynx are also paralysed, the airway usually needs to be protected by means of an endotracheal tube. Monitoring of paralysis is most easily provided by means of a peripheral nerve stimulator. This device intermittently sends short electrical pulses through the skin over a peripheral nerve while the contraction of a muscle supplied by that nerve is observed. The effects of muscle relaxants are commonly reversed at the termination of surgery by anticholinesterase drugs. Examples of skeletal muscle relaxants in use today are pancuronium, rocuronium, vecuronium, atracurium, mivacurium, and succinylcholine. Maintenance The duration of action of intravenous induction agents is generally 5 to 10 minutes, after which time spontaneous recovery of consciousness will occur. In order to prolong anaesthesia for the required duration (usually the duration of surgery), anaesthesia must be maintained. Usually this is achieved by allowing the patient to breathe a carefully controlled mixture of oxygen, nitrous oxide, and a volatile anaesthetic agent or by having a carefully controlled infusion of medication, usually propofol, through an intravenous catheter. The inhalation agents are transferred to the patient's brain via the lungs and the bloodstream, and the patient remains unconscious. Inhaled agents are frequently supplemented by intravenous anaesthetics, such as opioids (usually fentanyl or a fentanyl derivative) and sedative-hypnotics (usually propofol or midazolam). Though for a propofol-based anaesthetic, supplementation by inhalation agents is not required. At the end of surgery the volatile or intravenous anaesthetic is discontinued. Recovery of consciousness occurs when the concentration of anaesthetic in the brain drops below a certain level (usually within 1 to 30 minutes depending upon the duration of surgery). In the 1990s a novel method of maintaining anaesthesia was developed in Glasgow, UK. Called TCI (target controlled infusion), this involves using a computer controlled syringe driver (pump) to infuse propofol throughout the duration of surgery, removing the need for a volatile anaesthetic, and allowing pharmacologic principles to more precisely guide amount of infusion of the drug. Purported advantages include faster recovery from anaesthesia, reduced incidence of post-operative nausea and vomiting, and absence of a trigger for malignant hyperthermia. At present, TCI is not permitted in the United States] Other medications will occasionally be given to anaesthetized patients to treat side effects or prevent complications. These medications include antihypertensives to treat high blood pressure, drugs like ephedrine and phenylephrine to treat low blood pressure, drugs like albuterol to treat asthma or laryngospasm/bronchospasm, and drugs like epinephrine or diphenhydramine to treat allergic reactions. Sometimes glucocorticoids or antibiotics are given to prevent inflammation and infection, respectively. Postoperative care The anaesthesia should conclude with a pain-free awakening and a management plan for postoperative pain relief. This may be in the form of regional analgesia, oral, transdermal or parenteral medication. Minor surgical procedures are amenable to oral pain relief medications such as paracetamol and NSAIDs such as ibuprofen. Moderate levels of pain require the addition of mild opiates such as tramadol. Major surgical procedures may require a combination of modalities to confer adequate pain relief. Parenteral methods include patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) involving a strong opiate such as morphine, fentanyl or oxycodone. Here, to activate a syringe device, the patient presses a button and receives a preset dose or "bolus" of the drug (e.g. one milligram of morphine). The PCA device then "locks out" for a preset period, e.g. 5 minutes, to allow the drug to take effect. If the patient becomes too sleepy or sedated, they make no more morphine requests. This confers a fail safe aspect which is lacking in continuous opiate infusion techniques. Shivering is a frequent occurrence in the post-operative period. Apart from causing discomfort and exacerbating post-operative pain, shivering has been shown to increase oxygen consumption, catecholamine release, cardiac output, heart rate, blood pressure and intra-ocular pressure. There are a number of techniques used to reduce this occurrence, such as increasing the ambient temperature in theatre, using conventional or forced warm air blankets and using warmed intravenous fluids Perioperative mortality Main article: Perioperative mortality Most perioperative mortality is attributable to complications from the operation (such as haemorrhage, sepsis, and failure of vital organs) or pre-existing medical conditionsMost current estimates of perioperative mortality range from 1 death in 53 anaesthetics to 1 in 5,417 anaesthetics. However, a 1997 Canadian retrospective review of 2,830,000 oral surgical procedures in Ontario between 1973–1995 reported only four deaths in cases in which either an oral and maxillofacial surgeon or a dentist with specialized training in anaesthesia administered the general anaesthetic or deep sedation. The authors calculated an overall mortality rate of 1.4 per 1,000,000 The largest and most recent study of postoperative mortality was published in 2010. In this review of 3.7 million elective open surgical procedures performed on inpatients at 102 hospitals in the Netherlands during 1991–2005, postoperative mortality from all causes was observed in 67,879 patients, for an overall rate of 1.85%.The wide disparity between the results of these studies may be the result of differences in operational definitions and reporting sources. Mortality directly related to anaesthetic management is significantly less common, and may include such causes as pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents, asphyxiation[18] and anaphylaxis. These in turn may result from malfunction of anaesthesia-related equipment or more commonly, human error. A 1978 study found that 82% of preventable anaesthesia mishaps were the result of human error. In a 1954 review of 599,548 surgical procedures at 10 hospitals in the United States between 1948–1952, 384 deaths were attributed to anaesthesia, for an overall mortality rate of 0.64%. In 1984, after a television programme highlighting anaesthesia mishaps aired in the United States, American anaesthesiologist Ellison C. Pierce appointed a committee called the Anesthesia Patient Safety and Risk Management Committee of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. This committee was tasked with determining and reducing the causes of peri-anaesthetic morbidity and mortality. An outgrowth of this committee, the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation was created in 1985 as an independent, nonprofit corporation with the vision that "that no patient shall be harmed by anesthesia". As with perioperative mortality rates in general, the current mortality attributable to the management of general anaesthesia is controversial The incidence of perioperative mortality that is directly attributable to anaesthesia ranges from 1 in 6,795 to 1 in 200,200 anaesthetics. References 1. ^ Li X, Pearce RA (2000). "Effects of halothane on GABA(A) receptor kinetics: evidence for slowed agonist unbinding". J. Neurosci. 20 (3): 899–907. PMID 10648694. 2. ^ Harrison N, Simmonds M (1985). "Quantitative studies on some antagonists of N-methyl D-aspartate in slices of rat cerebral cortex". Br J Pharmacol 84 (2): 381–91. PMID 2858237. 3. ^ Bergendahl, H; Lönnqvist, PA; Eksborg, S (Feb 2006). "Clonidine in paediatric anaesthesia: review of the literature and comparison with benzodiazepines for anesthetic premedication". Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 50 (2): 135–43. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.00940.x. PMID 16430532. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/fulltext/118557949/HTMLSTART. Retrieved 09-08-2010. 4. ^ Dahmani, S; Brasher, C; Stany, I; Golmard, J; Skhiri, A; Bruneau, B; Nivoche, Y; Constant, I et al. (Jan 2010). "Premedication with clonidine is superior to benzodiazepines. A meta analysis of published studies". Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 54 (4): 397–402. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02207.x. PMID 20085541. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02207.x/pdf. Retrieved 09-08-2010. 5. ^ Rosenbaum, A; Kain, ZN; Larsson, P; Lönnqvist, PA; Wolf, AR (Sep 2009). "The place of premedication in pediatric practice". Paediatr Anaesth 19 (9): 817– 28. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.03114.x. PMID 19691689. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.03114.x/pdf. Retrieved 09-08-2010. 6. ^ Cox, RG; Nemish, U; Ewen, A; Crowe, MJ (Dec 2006). "Evidence-based clinical update: does premedication with oral midazolam lead to improved behavioural outcomes in children?". Can J Anaesth 53 (12): 1213–9. doi:10.1007/BF03021583. PMID 17142656. http://www.springerlink.com/content/8n317wx4w0136x35/fulltext.pdf. Retrieved 09-08-2010. 7. ^ Bozkurt, P (Jun 2007). "Premedication of the pediatric patient - anesthesia for the uncooperative child". Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 20 (3): 211–5. doi:10.1097/ACO.0b013e328105e0dd. PMID 17479023. http://journals.lww.com/coanesthesiology/Abstract/2007/06000/Premedication_of_the_pediatric_patient __.11.aspx. Retrieved 09-08-2010. Different Stages of Anesthesia: Stage Duration Physical Signs Onset Giving Anesthesia to loss of consciousness Physical Signs Excitement From loss of consciousness to loss of eyelid reflexes Irregular Heart beats and Breathing Surgical Anesthesia Loss of eyelid reflexes to depression of vital functions Total Unconsciousness Recovery or Danger Respiratory and circulatory failure No breathing and heart beat