Hypotheses and the Scientific Method FAQ

Hypotheses and the Scientific Method

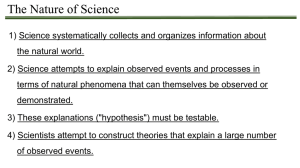

This is designed to help you learn how to formulate and test scientific hypotheses. The scientific method is a powerful way to learn about many kinds of things—it isn’t limited to science but can be extended to some other areas as well. It doesn’t extend to all areas, however. The arts, religion, and philosophy—all important areas—operate in other ways.

What is a hypothesis?

What is a prediction from a hypothesis?

What is a scientific hypothesis?

What are some simple examples that show the difference between scientific hypotheses and other types of hypotheses?

A hypothesis is a tentative answer to a well-formed question. Modern scientists commonly follow a five-step process (known as the scientific method ) when pursuing a problem or developing a theory . (1) They make an observation . This might be some phenomenon the scientist ran into by accident, but more often it will be something he or she observed while studying a problem. (2) They ask questions about the observation(s). (3) They form a hypothesis —a tentative answer to a question. (4) They make predictions based on the hypothesis. (5) They test the predictions. (For more on the scientific method and theories see the end of this FAQ.)

Any hypothesis has predictable consequences. Consider this example. Your TV won’t turn on. Question: why won’t it turn on? You can probably suggest several hypotheses to answer that question. One hypothesis would be “the TV won’t turn on because there has been a power failure.” If that hypothesis is true, we can predict that no other appliance on that circuit (such as a lamp) will turn on either. We can test that prediction by seeing whether the other appliances can be turned on.

If a hypothesis can’t give rise to predictions that could be tested and found false, it is not a scientific hypothesis . In principle, any scientific hypothesis is subject to testing and falsification. If no evidence could conceivably disprove it, a hypothesis is not scientific. Interestingly, hypotheses cannot be proven to be correct. They can continually be challenged by some new test or piece of evidence proving them to be false.

There is no limit to the number of hypotheses one might create. Scientific hypotheses, however, must meet the criteria above. Consider the following three examples:

1.

The moon is made of green cheese .

2.

Basketball is better than football .

3.

The entire universe is actually a figment of your imagination.

How can I create a hypothesis?

How can I test a hypothesis?

Are all three of these hypotheses scientific hypotheses?

None of them? Any of them? Think about each one.

The first one is a scientific hypothesis, because it could be disproved. (It has been disproved—most directly by sending astronauts who determined that they landed on rock, not on green cheese.)

The second is not a scientific hypothesis, because there is no way to disprove it—it is simply a matter of opinion.

The third is not a scientific hypothesis. It is certainly interesting, and it has been a topic in philosophical and logical debates for quite some time. How could that hypothesis be tested (and perhaps disproved)? If you come up with a suggestion for how to test it, then your suggestions could be figments of your imagination, too.

Maybe you argue with someone about it…but who is to say that you aren’t arguing with a figment of your imagination?

No matter what you do, you can’t disprove the possibility that you are living in a dream. The hypothesis is not a scientific hypothesis; there is no way in which it could be disproved.

A hypothesis begins with a question—the hypothesis is a tentative answer or explanation that addresses the question.

Suppose you are looking for something in the dark, using a flashlight. Your flashlight goes out. Your question is almost certainly “Why did the flashlight go out?” Stop and think for a moment… can you create one or two hypotheses

(answers to your question)?

One reasonable hypothesis would be: The batteries are dead.

Another reasonable hypothesis would be: The bulb has burned out .

Generate hypotheses by thinking of them as answers to questions. Remember, though: A hypothesis is a scientific hypothesis only if it could be tested and thus might be disproved by the failure of a prediction.

A hypothesis may be tested by running experiments, making observations in nature, or getting information from a reliable source. Either or both of the hypotheses about the flashlight can be tested by doing experiments. How?

How are hypotheses related to “the scientific method”?

What is a scientific theory?

The first hypothesis can be tested by replacing the batteries with new ones (that work, of course). If this doesn’t fix the flashlight, you have just disproved that hypothesis!

The second hypothesis can be tested by replacing the bulb with a new one.

For a nice, thorough definition and discussion of what a hypothesis is, check out this reference , especially the section called “Evaluating hypotheses.”

By considering the development and testing of hypotheses, we have just walked through the most important features of the scientific method , also known as the hypotheticodeductive method . The scientific method proceeds by observation , followed by forming questions , then developing hypotheses that might answer the questions, making testable predictions based on the hypotheses, and finally testing the predictions in an attempt to falsify them.

If a hypothesis stands up to repeated, challenging tests and passes them all, it may be “promoted” and called a theory .

A scientific theory is not a “wild theory” or “just a theory.”

It has been tested over and over again.