Word Document - Mysmu .edu mysmu.edu

advertisement

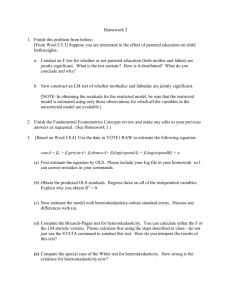

Econ107 Applied Econometrics Topic 9: Heteroskedasticity (Studenmund, Chapter 10) I. Definition and Problems We now relax another classical assumption. This is a problem that arises often with cross sections of individuals, households or firms. It can be a problem with time series data, too. Homoskedasticity exists when the variance of the disturbances is constant: Var ( i ) = E ( i2 ) = 2 Assumption of equal (homo) spread (skedasticity) in the distribution of the disturbances for all observations. Variance is a constant. Independent of anything else, including the values of the independent variables. Heteroskedasticity exists when the variance of the disturbances is variable: Var ( i ) = E ( i2 ) = i2 The variance of the disturbances can take on a different value for each observation in the sample. Most general specification. Takes on different values for each observation. More often, σi2 may be related to one or more of the independent variables. Heteroskedasticity violates one of the basic classical assumptions. Example: Suppose we estimate a cross-sectional savings function. The variance of the disturbances may increase with disposable income, due to increased 'discretionary income'. More income has to be devoted to basic necessities. Distributions flatten out as DI rises. Take 3 distinct income classes (low, medium and high) – two graphs. Other examples. Might be related to the size of some economic aggregate (e.g., corporation, metropolitan area, state or region). Page -2 What happens if we use OLS in a regression with known heteroskedasticity? (1) The estimated coefficients are still unbiased. Homoskedasticity is not a necessary condition for unbiasedness. Same result as multicollinearity. Page -3 (2) But the OLS estimators are inefficient. This means that they're no longer BLUE, like in the case of serial correlation. Different from multicollinearity. Return to the 2-variable regression: Y i = 0 + 1 X i + i with homoskedasticity: Var ( ˆ1 ) = xi2 2 with heteroskedasticity: xi2 i2 Var ( ˆ1 ) = ( xi2 )2 Of course if σi2=σ2, we can simplify: xi = Var ( ˆ1 ) = ( xi2 )2 xi2 2 2 2 Earlier formula for calculating the standard error depends on the assumption of homoskedasticity. It’s a ‘special case’ of the more general formula. OLS estimators will be inefficient. They’re no longer minimum variance. The formulae for the OLS estimators of the coefficients are still the same under heteroskedasticity. Intuition: We want the 'best fit' possible for our regression line. Our sample regression function should lie as close as possible to the population regression function. OLS 'equally weights' each observation. It assumes each observation contributes the same amount of 'information' to this estimation. With heterogeneity that is no longer appropriate. Observations should not be equally weighted. Those associated with a tighter distribution of i contribute more information, while those associated with a wider distribution of i contribute less information about the basis of this economic behaviour. A priori observations from wider distribution have more ‘potential error’. By disregarding heteroskedasticity and using the OLS formula, we would produce biased estimates of the standard errors. In general, we won't know the direction of the bias. As a result, statistical inference would be inappropriate. Page -4 Weighted Least Squares (WLS) WLS essentially takes advantage of this heterogeneity in its estimators. Assume σi2 is known. Transform the data by dividing by σi: Yi = i 0( 1 i ) + 1( X i ) + ( i ) i i or use ‘*’ to denote the transformed variables: * * * * Y i = 0W i + 1 X i + i where Wi* is the 'weight' given to the observation. This is just the inverse of the standard deviation. No longer a constant term in the regression. OLS estimation on the transformed model is WLS on the original model (denote the estimators by ̂ 0* and ̂1* ). But why did we do this? As a result: Var( *i ) = E( *i 2 ) = E [( i / i )2 ] = i2 = 1 i2 This means that the OLS estimators of the transformed data are BLUE, because the disturbances are now homoskedastic. Not only constant, also equal to 1. In this case ̂ 0* and ̂1* will be BLUE. The transformed model meets all the classical assumptions, including homoskedasticity. Recall that ̂ 0 and ̂1 are unbiased, but not efficient. Another way to motivate the distinction between OLS and WLS is to look at the 'objective functions' of the estimation. Under OLS we minimise the residual sum of squares: ei2 = ( Y i - ˆ0 - ˆ1 X i )2 But under WLS we minimise a weighted residual sum of squares: Page e i i -5 2 Couple things to note: 1. The formulae for WLS estimates of β0 and β1 aren’t worth committing to memory, so don’t write them down. The key is that they look similar to the formulae under homoskedasticity, except for the ‘weighting’ factor. True of both 2- and k-variable models. But with software packages, don’t have to know these. Just transform data and run the regression through the origin. 2. If σi = σ for all observations, then WLS estimators are OLS estimators. OLS is a special case of this more general procedure. II. Detection How do we know when our disturbances are heteroskedastic? The key is that we never observe the true disturbances or the distributions from which they are drawn. In other words, we never observe σi (at least not unless we see the entire population). For example, take our original example of the savings function. If we had the entire census of 4 million Singaporeans we’d be able to calculate it. We’d know how the dispersion in the disturbances varies with disposable income. But in samples we have to make an educated guess. We consider 4 diagnostic tests or indicators. 1. A Priori Information This might be 'anticipated' (e.g., based on past empirical work). Check the relevant literature in this area. Might show clear and persistent evidence of heteroskedastcity. For example, check both domestic and overseas studies of savings regressions. Is it a commonly reported problem in this empirical work? Key is that you see it coming. Remainder of the tests are ‘post-mortems’. Page -6 2. Graphical Methods Key: We'd like information on ui2, but all we ever see are ei2. We want to know whether or not these squared residuals exhibit any 'systematic pattern'. With homoskedasticity we'll see something like this: No relationship between ei2 and the explanatory variable. Even if we get this pattern, we can't rule out the possibility of heteroskedasticity. We may have to plot these squared residuals against other explanatory variables. The same could be done for the squared residuals and the fitted value. Alternatively, with heteroskedasticity what we'll see are patterns like this: Page -7 3. Park Test The Park test is just a ‘formalisation’ of the plotting of the squared residuals against another variable (often one of the explanatory variables). Use a two-step procedure: 1. Run OLS on your regression. Retain the squared residuals. Assume that: i2 = 2 Z i This implies a 'log-log' linear relationship between the squared residuals and Zi. 2. Estimate the following: ln ei2 = ln 2 + ln Z i + u i = + ln Z i + u i Test H0: β=0. If null is rejected, this suggests that heteroskedasticity is present. You need to choose which variables might be related to the squared residuals (often an independent variable is used). If β>0, then upward-sloping curved relationship. If β<0, then downward-sloping curved relationship. One problem is that rejection of H0 is “... sufficient, but not a necessary condition for heteroskedasticity”. Another problem is that this test imposes an assumed relationship between a particular variable and the squared residuals. 4. White Test This gets around the problems of the Park test that the disturbances are likely to be heteroskedastic. Use a three-step procedure: 1. Run OLS on your regression (assume Xi2 and Xi3 are the two independent variables). Retain the squared residuals. Page -8 2. Estimate the following auxiliary regression: 2 ei = 0 + 1 X 2i + 2 X 3i 3 X 2i 2 + 4 X 3i 5 X 2 i X 3i u i 2 3. Test the overall significance of the auxiliary regression. To do this, use nR22 . Under the null of homoskedasticity, nR22 follows the chi-square distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the number of slope coefficients in the auxiliary regression, where n is the sample size, R22 is the coefficient of determination of the auxiliary regression. III. Remedial Measures What do you do when heteroskedasticity is suspected? (i) When σi is known, transform data by dividing both dependent and independent variables by σi and run OLS. This is the weighted least squares procedure. Not a very interesting situation. This information is rarely available. (ii) When σi is unknown, determine the ‘likely form’ of the heteroskedasticity. Transform the data accordingly, and run weighted least squares. Two Examples: Suppose we have the following regression for a cross section of cities: CRi = 0 + 1 EXP i + 2 POPi + i where: CRi = Per capita crime rate. EXPi = Per capita expenditures on police. POPi = Population. The first slope coefficient picks up the ‘effectiveness’ of police expenditures at the margin (negative). The second says that crime might increase with the size of the metropolitan population (positive). Page -9 (1) Suppose we suspect that: Var ( i ) = E ( i2 ) = 2 POPi where σ2 is a constant. Transform the data and estimate the following: CRi = POP i 0 + 1 POP i EXP1 POP i + 2 POP i + POP i i POPi or CRi POPi = 0 1 + 1 EXP i + 2 POPi + ui POPi POPi The residuals are now homoskedastic. (The proof left to you as an exercise.) This doesn’t change the interpretation of the coefficients. Dividing both sides by the same variable. (2) Suppose we now suspect that: 2 Var ( i ) = E ( i2 ) = 2 Cˆ Ri where Cˆ Ri is the fitted value. Transform the data and estimate the following: 1 CRi POPi = 0 + 1 EXP i + 2 + ui Cˆ Ri Cˆ Ri Cˆ Ri Cˆ Ri The residuals are now homoskedastic. Operationally, this second example requires two steps: (1) Run OLS on the original equation with the untransformed data (recall that the estimated coefficients are still unbiased, although they are inefficient). (2) Transform the data by dividing the dependent and independent variables with these fitted values and estimate as above. Page - 10 (iii). Using heteroskedastic-corrected (HC or White) standard errors. Heteroskedasticity does not cause bias of OLS estimates but impacts the standard errors. HC technique directly adjusts the standard errors of OLS estimates to take account of heteroskedasticity. IV. Questions for Discussion: Q10.13 V. Computing Exercise: Johnson, Ch10, 1-5