Evidence-Based Medicine

advertisement

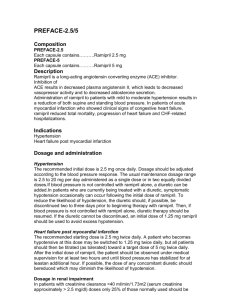

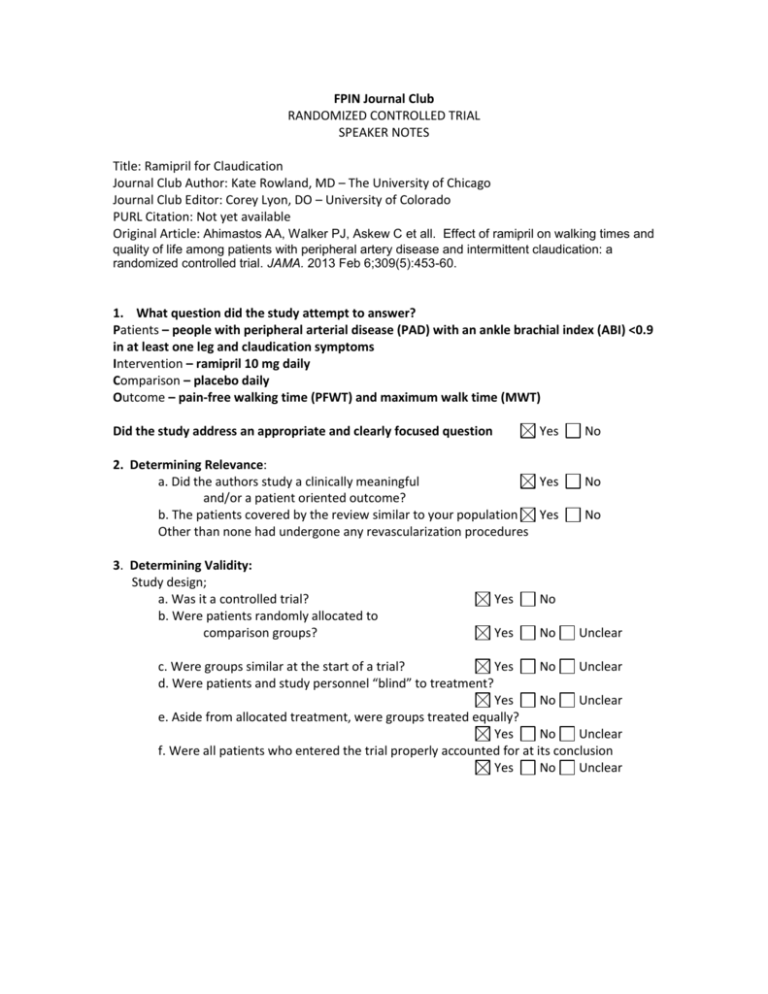

FPIN Journal Club RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL SPEAKER NOTES Title: Ramipril for Claudication Journal Club Author: Kate Rowland, MD – The University of Chicago Journal Club Editor: Corey Lyon, DO – University of Colorado PURL Citation: Not yet available Original Article: Ahimastos AA, Walker PJ, Askew C et all. Effect of ramipril on walking times and quality of life among patients with peripheral artery disease and intermittent claudication: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013 Feb 6;309(5):453-60. 1. What question did the study attempt to answer? Patients – people with peripheral arterial disease (PAD) with an ankle brachial index (ABI) <0.9 in at least one leg and claudication symptoms Intervention – ramipril 10 mg daily Comparison – placebo daily Outcome – pain-free walking time (PFWT) and maximum walk time (MWT) Did the study address an appropriate and clearly focused question Yes 2. Determining Relevance: a. Did the authors study a clinically meaningful Yes and/or a patient oriented outcome? b. The patients covered by the review similar to your population Yes Other than none had undergone any revascularization procedures 3. Determining Validity: Study design; a. Was it a controlled trial? b. Were patients randomly allocated to comparison groups? Yes No Yes No No No No Unclear c. Were groups similar at the start of a trial? Yes No Unclear d. Were patients and study personnel “blind” to treatment? Yes No Unclear e. Aside from allocated treatment, were groups treated equally? Yes No Unclear f. Were all patients who entered the trial properly accounted for at its conclusion Yes No Unclear 4. What are the results? a. What are the overall results of the study? At the end of the study, the people who got the ramipril were able to walk 255 seconds longer (maximum walk time, 95% CI 215-295, p<0.001) than those who got placebo. Their painfree walk time was 75 seconds longer than those who got placebo (95% CI 60-89s, p<0.001). Patients were able to walk 255 seconds (about 4.25 minutes) longer with the ramipril. This does not seem like a big difference, but it is about equivalent to their maximum walking time at the beginning of the study (approximately 230 seconds), meaning that the people in the ramipril group doubled their maximum walking time. The median distance score improved by 13.8 (95% CI, 12.2 to 15.5), the speed score by 13.3 (95% CI, 11.9 to 15.2), and the stair climbing score by 25.2 (95% CI, 25.1 to 29.4). The physical quality of life score improved b y 8.2 (95% CI, 3.6-11.4; p=.02) but ramipril was not associated with change in the overall mental quality of life. Dizziness was reported following initiation of treament in 5.6% of patients. Persisent cough was noted by 6.6% of the patients. One patient reported chest pain and another had pronounced ST-segment depression . We think many patients would accept the addition of ramipril in exchange for doubling their capacity to walk. b. Are the results statistically significant? c. Are the results clinically significant? d. Were there other factors that might have affected the outcome? Yes Yes No No Yes No 5. Applying the evidence: a. If the findings are valid and relevant, will this change your current practice? Yes No b. Is the change in practice something that can be done in a medical care setting of a family physician? Yes No c. Can the results be implemented? Yes No d. Are there any barrier to immediate implementation? Yes No e. How was this study funded? It was funded by an Australian medical foundation. Since the medication in question is generic and available for relatively cheap (quick internet search shows 30 tabs for $34), the funding and the authors’ disclosures do not seem to play any relevant conflict of interests. 6. Teaching Points This article is an example of a well-done randomized controlled trial comparing a cheap, available medication given for a common condition to improve an outcome that likely matters to a patient. It also highlights the need for careful analysis of the types of outcomes studied. When reading an article, you have to know whether the outcomes are ones that matter to your patients. We typically ask: are the outcomes patient-oriented or disease-oriented? A disease-oriented outcome is one that measures only pathologic or physiologic markers. A patient-oriented outcome is one that relates to patient care, patient experience, or patient results. Examples of the differences between disease oriented and patient oriented outcomes can be seen in the table below. Disease oriented outcome Blood pressure Blood sugar Newborn respiratory rate LDL HemoglobinA1c levels Percentage of skin area affected Degrees of glenohumoral separation seen on MRI Patient oriented outcome Strokes; disability from stroke Diabetic nephropathy NICU admissions Cardiovascular mortality Quality of life scale Pain measured on a visual analog scale Clinical instability as measured by re-dislocation Patient-oriented outcomes are always preferable because disease-oriented outcomes can be misleading. It is always tempting (and often reasonable) to assume that because the LDL goes down, the rate of cardiovascular mortality will go down as well, but that’s not always the case. Example: a study of the use of erythropoietin in patients on hemodialysis for end-stage kidney disease (ESRD) found that patients whose anemia was corrected to a ‘normal’ level (mean 13.7mg/dl) actually had more adverse events such as stroke, CHF, and MI, than patients whose anemia was corrected to a mean of 11.3 mg/dl. Quality of life indicators were similar in both groups. The disease-oriented outcome is the hemoglobin level; it seemed reasonable that higher would be better. However, when the patient-oriented outcomes (adverse events and quality of life) were measured, the lower hemoglobin levels were found to be better. Ref: Singh, Ajay K., Szczech, Lynda, Tang, Kezhen L., Barnhart, Huiman, Sapp, Shelly, Wolfson, Marsha, Reddan, Donal, the CHOIR Investigators, Correction of Anemia with Epoetin Alfa in Chronic Kidney Disease N Engl J Med 2006 355: 2085-2098 This study chose patient-oriented outcomes. In addition to studying ABIs or degree of blockage, it studied walking times. It is just extra interesting that many of the disease-oriented outcomes are equivalent, while the patient-oriented outcomes are markedly different.