Natural Hazard Risk Management in the Caribbean: Technical Annex

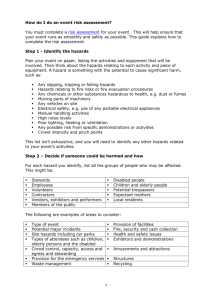

advertisement