Family Resilience and Good Child Outcomes

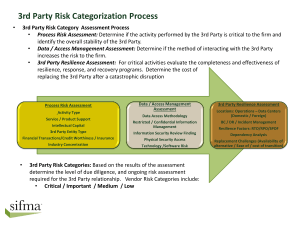

advertisement