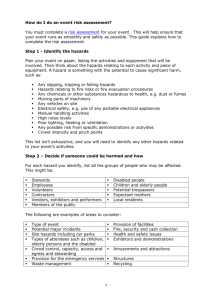

Health and Safety Management Systems

advertisement