Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New

advertisement

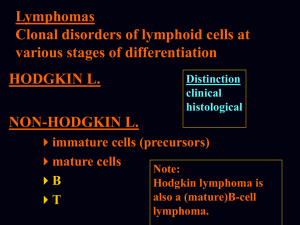

Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional National Lymphoma Tumour Standards Working Group 2013 Citation: National Lymphoma Tumour Standards Working Group. 2013. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand - Provisional. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Published in December 2013 by the Ministry of Health PO Box 5013, Wellington 6145, New Zealand ISBN 978-0-478-41539-1 HP 5742 This document is available through the Ministry of Health website: www.health.govt.nz or from the regional cancer network websites: www.northerncancernetwork.org.nz www.midland cancernetwork.org.nz www.centralcancernetwork.org.nz www.southerncancernetwork.org.nz Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 Background ..................................................................................................... 1 Objective ......................................................................................................... 1 How the lymphoma service standards were developed ................................... 2 Equity and Whānau Ora .................................................................................. 2 Summary of the clinical standards for the management of lymphoma services ........................................................................................................... 4 Standards of service provision pathway ........................................................... 4 Summary of standards..................................................................................... 5 1 Timely Access to Services ............................................................................... 8 Good practice points ........................................................................................ 9 2 Referral and Communication ......................................................................... 10 Rationale ....................................................................................................... 10 Good practice points ...................................................................................... 10 3 Investigation, Diagnosis and Staging ............................................................. 12 Rationale ....................................................................................................... 12 Good practice points ...................................................................................... 12 4 Multidisciplinary Care ..................................................................................... 15 Rationale ....................................................................................................... 15 Good practice points ...................................................................................... 15 5 Supportive Care............................................................................................. 17 Rationale ....................................................................................................... 17 Good practice points ...................................................................................... 17 6 Care Coordination ......................................................................................... 19 Rationale ....................................................................................................... 19 Good practice points ...................................................................................... 19 7 Treatment ...................................................................................................... 21 Rationale ....................................................................................................... 21 Good practice points ...................................................................................... 22 8 Follow-up and Surveillance ............................................................................ 24 Rationale ....................................................................................................... 24 Good practice points ...................................................................................... 24 Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional iii 9 Clinical Performance Monitoring and Research ............................................. 26 Rationale ....................................................................................................... 26 Good practice points ..................................................................................... 26 Appendices iv Appendix 1: National Lymphoma Tumour Standards Working Group Membership............................................................................ 28 Appendix 2: Glossary ................................................................................. 29 Appendix 3: The Lymphoma Patient Pathway ............................................ 34 Appendix 4: Recommended GP Referral Form .......................................... 35 Appendix 5: References ............................................................................. 37 Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional Introduction Background Lymphoma is a lymph node cancer of both Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin subtypes. The incidence in 2009 in New Zealand was 15.1 cases per 100,000 New Zealanders; this has increased over time. (In 1994, only 11.4 per 100,000 people were diagnosed with lymphoma.) This is a worldwide trend. The incidence is higher in men (18.4/100,000) than in women (12.2/100,000) (Ministry of Health 2012a). Although the incidence of lymphoma, like most cancers, increases with advancing age, some lymphomas – in particular Hodgkin lymphoma – are more common in younger patients. The incidence of Hodgkin overall is 3 per 100,000, and 70 percent of patients are in the 15–45-year age group (Ministry of Health 2012b). Early diagnosis and intervention are therefore critical. Lymphoma is not especially amenable to lifestyle modification programmes, and affects all New Zealanders without a significant ethnic bias. Lymphoma is generally very responsive to medical treatment. Ministry of Health statistics1 indicate that the death rate has reduced over time; for example, from 5.0 per 100,000 in 1995 to 4.7 per 100,000 in 2009. Despite being highly amenable to treatment, lymphoma is the fifth most common cause of cancer-related death in both men and women. According to Ministry of Health statistics, incidence of lymphoma in the Māori population is similar to that in the general population, although the Māori lymphoma death rate is slightly higher than non-Māori, at 5.2 per 100,000 per year. This likely reflects the poor access among Māori to appropriate and timely management. It is expected that a more streamlined approach to the diagnosis and management of lymphoma will result in an improvement in outcomes for all patients with lymphoma in New Zealand. Objective The scope of this document is the management of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma for all patients 15 years and over. Tumour standards for all cancers are being developed as a part of the Ministry of Health’s ‘Faster Cancer Treatment’ (FCT) programme’s approach to ensuring timely clinical care for patients with cancer. When used as a quality improvement tool, the standards will promote nationally coordinated and consistent standards of service provision across New Zealand. They aim to ensure efficient and sustainable bestpractice management of tumours, with a focus on equity. 1 Available through Cancer Control New Zealand: see www.cancercontrolnz.govt.nz/cancer-registry. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 1 The standards will be the same for all ethnic groups. However, we expect that in implementing the standards district health boards (DHBs) may need to tailor their efforts to meet the specific needs of populations with comparatively poorer health outcomes, such as Māori and Pacific people. How the lymphoma service standards were developed The National Haematology Working Group agreed that there should be two groups set up to work on haematology tumours: lymphomas and myeloma. The Lymphoma Tumour Standards were developed by a skilled working group representing key specialties and interests across lymphoma pathways of care (see Appendix 1). The National Lymphoma Tumour Standards Working Group had access to expert advisors in key content, and included Māori and consumer representation. Tumour-specific national standards were first developed for lung cancer in the Standards of Service Provision for Lung Cancer Patients in New Zealand (National Lung Cancer Working Group 2011); these standards have already been used by DHBs to inform improvements to service delivery and clinical practice. Subsequently provisional standards have been developed for an additional ten tumour types: bowel, breast, gynaecological, lymphoma, melanoma, myeloma, head and neck, sarcoma, thyroid and upper gastrointestinal. The Ministry of Health required all tumour standard working groups to: Maintain a focus on achieving equity and whānau ora when developing service standards, patient pathways and service frameworks by ensuring an alignment with the Reducing Inequalities in Health Framework and its principles (Ministry of Health 2002). These standards recognise the need for evidence-based practice. Numerous evidence-based guidelines and standards already exist, so the standards in this document have largely been developed by referring to established international guidelines in the haematology tumour stream (see Appendix 5). Equity and Whānau Ora Health inequities or health disparities are avoidable, unnecessary and unjust differences in the health of groups of people. In New Zealand, ethnic identity is an important dimension of health disparities. Cancer is a significant health concern for Māori, and has a major and disproportionate impact on Māori communities. 2 Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional Inequities exist between Māori and non-Māori in exposure to risk and protective factors for cancer, in incidence and outcomes, and in access to cancer services. According to Ministry of Health data, incidence of lymphoma in the Māori population is similar to the general population, although the death rate attributable to lymphoma for Māori is slightly higher than it is for non-Māori, at 5.2 per 100,000 per year. This likely reflects the poor access of many Māori to appropriate and timely management. Barriers to health care are recognised as multidimensional, and include health system and health care factors (eg, institutional values, workforce composition, service configuration and location), as well as patient factors (eg, socioeconomic position, transportation and patient values). Addressing these factors requires a population health approach that takes account of all the influences on health and how they can be tackled to improve health outcomes. A Whānau Ora approach to health care recognises the interdependence of people; health and wellbeing are influenced and affected by the ‘collective’ as well as the individual. It is important to work with people in their social contexts, and not just with their physical symptoms. The outcome of the Whānau Ora approach in health will be improved health outcomes for family/whānau through quality services that are integrated (across social sectors and within health), responsive and patient/family/whānau-centred. These standards will address equity for Māori patients with lymphoma in the following ways. The standards focus on improving access to diagnosis and treatment for all patients, including Māori and Pacific. There will be a focus on potential points of delay in diagnosis and management for Māori and Pacific people. Ethnicity data will be collected on all access measures and the FCT indicators, and will be used to identify and address disparities. Ethnicity data will be collected on mortality, morbidity and disability. Good practice points include health literacy training and cultural competency for all health professionals involved in patient care. Information developed or provided to patients and their family will meet Ministry of Health guidelines (Ministry of Health 2012d). Care coordination will involve Māori expertise and providers in multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) and networks. Māori will be prioritised in the piloting of initiatives in service delivery to reduce inequalities. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 3 Summary of the clinical standards for the management of lymphoma services Format of the standards Each cluster of standards has a title that summarises the step of the patient journey or the area on which the standards are focused. This is followed by the standard itself, which explains the level of performance to be achieved. The rationale section explains why the standard is considered to be important. Attached to the clusters of standards are good practice points. Good practice points are supported by either the international literature, the opinion of the National Lymphoma Tumour Standard Working Group or the consensus of feedback from consultation with New Zealand clinicians involved in providing care to patients with lymphoma. Also attached to each cluster are the requirements for monitoring the individual standards. Standards of service provision pathway The lymphoma tumour standards are reflected in the following pathway. 4 Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional Summary of standards The standards for the management of lymphoma have been divided into nine clusters: timely access to services referral and communication investigation, diagnosis and staging multidisciplinary care supportive care care coordination treatment follow-up and surveillance clinical performance monitoring and research. The standards are as follows. Timely access to services Standard 1.1: Patients referred urgently with a high suspicion of lymphoma receive their first cancer treatment or other management within 62 days. Standard 1.2: Patients referred urgently with a high suspicion of lymphoma have their first specialist assessment (FSA) within 14 days of referral. Standard 1.3: Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of lymphoma receive their first cancer treatment or other management within 31 days of the decision to treat. Standard 1.4: Patients needing radiotherapy or systemic therapy receive their first treatment within four weeks of the decision to treat. Referral and communication Standard 2.1: Patients with suspected lymphoma are referred to secondary and tertiary care following an agreed referral pathway. Standard 2.2: Patients and their general practitioners (GPs) are provided with verbal and written information about their lymphoma, diagnostic procedures, treatment options (including effectiveness and risks), final treatment plan and support services. Standard 2.3: Communications between health care providers include the patient’s name, date of birth and National Health Index (NHI) number, and are ideally electronic. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 5 Investigation, diagnosis and staging Standard 3.1: Imaging investigations follow standardised imaging pathways agreed to by New Zealand cancer treatment centres based on the Royal College of Radiologists’ Cancer Imaging Guidelines. Standard 3.2: Diagnosis of patients occurs through lymphoma excision biopsy (over core biopsy or fine needle aspiration). Standard 3.3:All patients with a provisional histological diagnosis of lymphoma have their diagnosis reviewed and confirmed by a specialist pathologist affiliated to a lymphoma multidisciplinary meeting (MDM). Standard 3.4: The histology of excised lymphoma specimens is reported in a synoptic format. Standard 3.5: Imaging investigations for lymphoma are completed and reported within two weeks from referral unless clinically urgent. Standard 3.6: Appropriate imaging facilities, including timely access to advanced imaging modalities, are available. Standard 3.7: Investigations provide sufficient information to give each patient an accurate diagnosis and staging. Multidisciplinary care Standard 4.1: All patients with confirmed lymphoma have their treatment plan discussed at an MDM; recommendations are clearly documented in the patient’s medical records and communicated to the patient, the treating clinician and the patient’s GP within one week. Supportive care Standard 5.1: All patients with lymphoma and their family/whānau have equitable and coordinated access to appropriate medical, allied health and supportive care services, in accordance with Guidance for Improving Supportive Care for Adults with Cancer in New Zealand (Ministry of Health 2010). Standard 5.2: All patients with a confirmed diagnosis of lymphoma have access to ongoing psychosocial services. Care coordination Standard 6.1: All patients with lymphoma have access to a haematology clinical nurse specialist or other health professional who is a member of the MDM to help coordinate all aspects of their care. 6 Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional Treatment Standard 7.1: All patients with lymphoma have a documented care plan prior to starting treatment; this is formulated and endorsed at an MDM in the majority of cases. Standard 7.2: Where appropriate, advice regarding the impact of treatment on fertility and referral for consultation with a fertility specialist is offered. Standard 7.3: Detailed written treatment protocols are used for the management of lymphoma. Standard 7.4: Patients are offered early access to palliative care services when there are complex symptom control issues, when curative treatment cannot be offered or if curative treatment is declined. Follow-up and surveillance Standard 8.1: Follow-up plans include clinical review and potential late toxicities by appropriate members of the MDT, working in conjunction with the patient, their family/whānau and their GP. Standard 8.2: Women under the age of 40 treated with radiotherapy for lymphoma undergo individualised breast screening if breast tissue was included in their radiotherapy treatment. Clinical performance monitoring and research Standard 9.1: Data relating to lymphoma beyond the fields required by the Cancer Registry, including treatment data, are reported to existing and planned national repositories using nationally agreed data set fields. Standard 9.2: Patients with lymphoma are offered the opportunity to participate in research projects and clinical trials where these are available. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 7 1 Timely Access to Services Standard 1.1 Patients referred urgently with a high suspicion of lymphoma receive their first cancer treatment or other management within 62 days. Standard 1.2 Patients referred urgently with a high suspicion of lymphoma have their FSA within 14 days of referral. Standard 1.3 Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of lymphoma receive their first lymphoma treatment or other management within 31 days of the decision to treat. Standard 1.4 Patients needing radiotherapy or systemic therapy receive their first treatment within four weeks of the decision to treat. Rationale Timely access to quality cancer management is important to support good health outcomes for New Zealanders. Key components of successful cancer management include early recognition and reporting of symptoms, expertise in identifying patients requiring prompt referral and rapid access to investigations and treatment. A suspicion of lymphoma or lymphoma diagnosis is very stressful for patients and their family/whānau. It is important that patients and family/whānau know how quickly patients can receive treatment. Long waiting times may affect local control and survival benefit for some cancer patients, and can result in delayed symptom management for palliative patients. The standards in this cluster ensure that: patients receive quality clinical care patients are managed through the pathway, and experience well-coordinated service delivery delays are avoided as far as possible. The FCT indicators (Standards 1.1–1.3) adopt a timed patient pathway approach across surgical and non-surgical cancer treatment, and apply to inpatients, outpatients and day patients. Shorter waits for cancer treatments is a government health target for all radiation treatment patients and systemic therapy outpatients. 8 Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional The four-week timeframe for radiation treatment (Standard 1.4) is based on international best-practice guidelines and recommendations that have been endorsed by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists Faculty of Radiation Oncology and the National Cancer Treatment Advisory Group. All DHBs are currently achieving the target. Good practice points 1.1 GP practices refer to secondary care services within one working day of receiving a diagnostic result indicating lymphoma. 1.2 Reports are distributed electronically. 1.3 Systems are developed at a local level to manage the further investigation of abnormalities suggestive of lymphoma incidentally found by radiological imaging. 1.4 All patients with a confirmed diagnosis of lymphoma are offered a psychosocial assessment, ideally before treatment commences. 1.5 Māori and Pacific peoples tend to wait longer for cancer care. Practitioners are alert to potential points of delay in access to diagnosis and management. Monitoring requirements MR1A Track FCT indicators. MR1B Collect and analyse ethnicity data on all access targets and indicators. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 9 2 Referral and Communication Standard 2.1 Patients with suspected lymphoma are referred to secondary and tertiary care following an agreed referral pathway. Standard 2.2 Patients and their GPs are provided with verbal and written information about their lymphoma, diagnostic procedures, treatment options (including effectiveness and risks), final treatment plan and support services. Standard 2.3 Communications between health care providers include the patient’s name, date of birth and NHI number, and are ideally electronic. Rationale The purpose of the referral pathway is to ensure that all patients with suspected lymphoma are referred to the most appropriate health care service, and that appropriate standardised information is available in the referral (see Appendix 3). Effective health education resources may contribute to the protection of patient safety, improved health outcomes and the empowerment of individuals and their family/whānau to increase control over their health and wellbeing through increasing health literacy levels. As indicated in Rauemi Atawhai: A guide to developing health education resources in New Zealand (Ministry of Health 2012d), a person with a good level of health literacy is able to find, understand and evaluate health information and services easily in order to make effective health decisions. Good practice points 10 2.1 Many patients with lymphoma are identified in primary care; patients may present with a range of clinical features. Practitioners are alert to the wide range of potential clinical symptoms and signs of lymphoma. 2.2 Patients with a suspected lymphoma are investigated and referred to a haematologist or oncologist. (Patients with a positive result on lymph node fine needle aspiration are immediately discussed with/referred to a haematologist or oncologist, in order to develop an appropriate plan for excisional biopsy and specialist review.) 2.3 Patient referrals include all relevant laboratory and imaging results available (see the recommended GP referral form in Appendix 4). Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional Monitoring requirements MR2A Provide evidence of clear and accessible referral pathways. MR2B Audit correspondence between secondary/tertiary care and GPs. MR2C Provide evidence of culturally appropriate patient and family/whānau satisfaction surveys, and audit the complaints process. MR2D Audit documentation between health care providers. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 11 3 Investigation, Diagnosis and Staging Standard 3.1 Imaging investigations follow standardised imaging pathways agreed to by New Zealand cancer treatment centres based on the Royal College of Radiologists’ Cancer Imaging Guidelines. Standard 3.2 Diagnosis of patients occurs through lymphoma excision biopsy (over core biopsy or fine needle aspiration). Standard 3.3 All patients with a provisional histological diagnosis of lymphoma have their diagnosis reviewed and confirmed by a specialist pathologist affiliated to a lymphoma MDM. Standard 3.4 The histology of excised lymphoma specimens is reported in a synoptic format. Standard 3.5 Imaging investigations for lymphoma are completed and reported within two weeks from referral unless clinically urgent. Standard 3.6 Appropriate imaging facilities, including timely access to advanced imaging modalities, are available. Standard 3.7 Investigations provide sufficient information to give each patient an accurate diagnosis and staging. Rationale Successful treatment of lymphoma depends on accurate diagnosis and staging. Good practice points Pathology 12 3.1 Pathologist fine needle aspiration is a safe, cost-effective and accurate test in the initial assessment of palpable lymph nodes in both community and hospital settings. In the case of a suspicious or positive diagnosis of lymphoma, patients are promptly referred for further assessment. Final classification and treatment decisions are not made on a fine needle aspiration diagnosis alone. Limitations of the test – particularly false negative diagnoses – are recognised. 3.2 It is recognised that in some clinical situations an excision biopsy is not practical, in which case assessment of core biopsies is satisfactory. All tissue submitted for histologic examination is sent fresh for ancillary flow cytometry and/or cytogenetic studies. An integrated report is produced for new lymphoma diagnoses. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional 3.3 Appropriate cases are reviewed at an MDM. Cases are clinician-selected and patient selection is targeted to optimise resources and ensure equity of access to expert opinion. 3.4 Patients, and particularly Māori and Pacific patients, are given the option of retaining tissue postoperatively (NZGG 2009). Clinical examination 3.5 Patients are examined for lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, pleural effusions, ascites and skin lesions. Bone marrow biopsy 3.6 A bone marrow biopsy is part of the routine staging of most non-Hodgkin lymphoma. 3.7 A bone marrow biopsy is not necessary for early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma, and may be replaced by positron emission tomography and computed tomography (PET-CT) scanning in advanced Hodgkin lymphoma staging. 3.8 A bone marrow biopsy may not be necessary for low-grade follicular lymphoma if a ‘watch and wait’ approach is being taken. Imaging 3.9 A chest X-ray forms part of initial investigation of symptoms. There is no role for abdominal X-rays. 3.10 All patients with newly diagnosed lymphoma require staging with a CT scan of neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis with contrast. 3.11 PET-CT scanning is undertaken in biopsy-proven cases of: Hodgkin lymphoma high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma, if this has not been fully staged with CT and/or PET-CT will potentially alter stage or management follicular lymphoma, where the PET-CT result may alter the stage or treatment toxicity radiotherapy field, or change the focus of the management plan from radiotherapy to observation. 3.12 PET-CT scanning is available in four regions throughout New Zealand, on established pathways. All machines are capable of performing high-resolution diagnostic contrast-enhanced CT concurrent with PET imaging. Separate CT scans may therefore not be required in cases where PET-CT is indicated (see Good practice point 3.11 above), minimising cost and radiation exposure for the patient. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 13 3.13 Interim (mid-cycle) CT or PET-CT is restricted to situations where clinical management will be affected, and to clinical trials. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound scan is performed if CT or PET-CT is contraindicated; for example, for pregnant patients. Restaging at end of treatment 3.14 At the end of treatment, imaging is undertaken as noted above, including through a CT scan of chest, abdomen/pelvis and (where appropriate) neck. 3.15 PET-CT scanning is recommended for all patients with Hodgkin lymphoma and suggested in all those with high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma with a residual mass after treatment (~80% and 40% respectively). Biopsy confirmation is necessary for equivocal findings. Relapse 3.16 In the case of relapse, imaging is undertaken as noted above, including through PET-CT scanning where it would influence clinical management. 3.17 In many cases relapse requires confirmation with repeat biopsy. Monitoring requirements 14 MR3A Ensure that radiology departments work to standardised imaging protocols. MR3B Ensure that MDMs provide evidence of appropriate radiological imaging. MR3C Ensure that MDMs provide evidence of pathological review and confirmation. MR3D Ensure that pathology departments keep a register of synoptic reports. MR3E Ensure that MDMs audit pathology reviews. MR3F Ensure that MDMs provide records of all patient staging prior to treatment. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional 4 Multidisciplinary Care Standard 4.1 All patients with confirmed lymphoma have their treatment plan discussed at an MDM; recommendations are clearly documented in the patient’s medical records and communicated to the patient, the treating clinician and the patient’s GP within one week. Rationale International evidence shows that multidisciplinary care is a key aspect to providing best-practice treatment and care for patients with cancer. Multidisciplinary care involves a team approach to treatment planning and care provision along the complete patient cancer pathway. Cancer MDMs are part of the philosophy of multidisciplinary care. Effective MDMs result in positive outcomes for patients receiving the care, for health professionals involved in providing the care and for health services overall. Benefits include improved treatment planning, improved equity of patient outcomes, more patients being offered the opportunity to enter into relevant clinical trials, improved continuity of care and less service duplication, improved coordination of services, improved communication between care providers and more efficient use of time and resources. Presentation at an MDM may mean only registration of the case and collection of agreed baseline data. Discussion may not be required, depending on the agreed criteria for presentation at that MDM. Good practice points 4.1 MDMs are governed by agreed terms of reference, and written protocols describe the organisation and content of the meeting. 4.2 A chair is appointed according to the terms of reference. Core members (see Ministry of Health 2012b) are present for the discussion of all cases where their input is needed. 4.3 Locally agreed referral pathways are established with clear information as to who can refer, how to refer and the timeframes within which referrals will be expected (along with processes for late referrals). Agreed criteria determine which patients should be discussed at the MDM. 4.4 A role representing a single point of coordination for MDMs is established, to support participating clinicians. Treatment recommendations agreed by participants are documented during the meeting and recorded in patients’ medical records. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 15 4.5 Lymphoma-specific core data is collected prior to and during the MDM. Data sets for use in clinical audit and pathway monitoring are consistently and routinely captured, for ongoing quality improvement. 4.6 Patients are informed about the MDM prior to the presentation of their case. They are then informed about the MDM’s recommendations and, in consultation with members of the treating team, make their own final decisions about their treatment and care plan. 4.7 Established processes govern communication of recommendations to patients, GPs and clinical teams within locally agreed timeframes. The MDM identifies a lead clinical team member to discuss the MDM’s recommendations with the patient. Monitoring requirements 16 MR4A Ensure that MDMs audit patients registered at the MDM. MR4B Ensure that MDMs audit treatment recommendations and following communications. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional 5 Supportive Care Standard 5.1 All patients with lymphoma and their family/whānau have equitable and coordinated access to appropriate medical, allied health and supportive care services, in accordance with Guidance for Improving Supportive Care for Adults with Cancer in New Zealand (Ministry of Health 2010). Standard 5.2 All patients with a confirmed diagnosis of lymphoma have access to ongoing psychosocial services. Rationale The psychological, social, physical and spiritual needs of cancer patients are many and varied. These needs can to a large extent be met by allied health care teams in hospitals and in the community. Adults with cancer enjoy improved quality of life following needs assessment and provision of supportive care. Non-government organisations, including the Cancer Society, perform an important role in providing supportive care. Good practice points 5.1 All patients have their supportive care and psychosocial needs assessed using validated tools and documented at the commencement of treatment, at appropriate intervals or times of significant change, and as clinically needed. 5.2 Patients are given access to services appropriate to their individual (physical, social, cultural, emotional, psychological, psychosocial and spiritual) needs. 5.3 Patients are offered referral to age-appropriate relevant support groups (most often cancer-specific non-governmental organisations). Referral to adolescent and young adult cancer services is appropriate for lymphoma patients under the age of 25. 5.4 Patients experiencing significant distress or disturbance are referred to health practitioners with the requisite specialist skills. 5.5 Where demand for psychological care services exceeds capacity, strategies are in place to meet patients’ needs through external organisations. 5.6 Supportive care services are culturally appropriate for all patients, including Māori and Pacific people and those of other ethnicities. 5.7 Clinical and supportive care information is provided in written and verbal language that is clear, accurate, unbiased and respectful of the patient’s cultural, spiritual and ethical beliefs, and that is age-appropriate. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 17 5.8 5.9 Information provided to patients may include: general background information about lymphoma detailed information on treatment options and specific local arrangements, including information about the MDM and support services, and whom the patient should contact if necessary details of local self-help/support groups and other appropriate organisations information related to the National Travel Assistance Scheme (Ministry of Health 2006) information about healthy living during and after cancer treatment. Health professionals ensure that patients understand the information provided, or refer them on to suitably qualified service providers/advisors who can help. 5.10 Interpreter or translation services are provided for patients and family/whānau who have limited English. 5.11 Health professionals take every opportunity to advocate for their patient. This could include supporting and educating patients regarding their disease, as well as encouraging patients to become more involved in their own care. 5.12 All clinicians responsible for communicating with patients and their family/whānau complete health literacy training. 5.13 All information developed for or provided to patients and their family/whānau meets Ministry of Health Guidelines (Ministry of Health 2012d). Monitoring requirements 18 MR5A Routinely review patient complaints and feedback across all contributing services. MR5B Audit referrals to appropriate cancer non-government organisations. MR5C Audit patient satisfaction surveys. MR5D Provide evidence of culturally appropriate patient and family/whānau satisfaction surveys, and audit complaints processes. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional 6 Care Coordination Standard 6.1 All patients with lymphoma have access to a haematology nurse specialist or other health professional who is a member of the MDM to help coordinate all aspects of their care. Rationale The cancer journey is complex, and it is not uncommon for a patient to be seen by many specialists within and across multiple DHBs and across the public and private sectors. Care coordinators are individuals (usually specialist nurses or allied health professionals) who have an in-depth/specialist knowledge of lymphomas and their treatment and who can act as advocates for patients, facilitating the coordination of the diagnostic and treatment pathway, providing continuity and ensuring patients know how to access information and advice. Good practice points 6.1 Patients are provided with their care coordinator’s name and contact details within seven days of diagnosis. This person is the single point of contact for patients and their family/whānau throughout the lymphoma journey. 6.2 All regional cancer centres employ a dedicated clinical nurse specialist who has knowledge about the disease process and treatment modalities and is able to undertake comprehensive patient assessment and assist with planning patient care. 6.3 Discharge planning is comprehensive when patients transfer between regional areas/hospitals for ongoing and follow-up care. 6.4 Sometimes, such as during long-term follow-up, the care coordinator role may be undertaken by other staff; for example, a primary care team member or other specialist, as appropriate. 6.5 Educational programmes are provided to all health care professionals so that they can develop effective haematology knowledge and skills to ensure care is planned and delivered safely. 6.6 Services routinely use a tool to assess psychological and social needs (such as the ‘Distress Thermometer’ (Baken and Woolley 2011). Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 19 Monitoring requirements 20 MR6A Audit patient records and clinical notes on contact points between care coordinators and patients. MR6B Routinely review patient complaints and feedback across services. MR6C Audit patient satisfaction surveys. MR6D Ensure that MDMs provide records of identified care coordinators. MR6E Provide evidence of culturally appropriate patient and family/whānau satisfaction surveys, and audit complaints processes. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional 7 Treatment Standard 7.1 All patients with lymphoma have a documented care plan prior to starting treatment; this is formulated and endorsed at an MDM in the majority of cases. Standard 7.2 Where appropriate, advice regarding the impact of treatment on fertility and referral for consultation with a fertility specialist is offered. Standard 7.3 Detailed written treatment protocols are used for the management of lymphoma. Standard 7.4 Patients are offered early access to palliative care services when there are complex symptom control issues, when curative treatment cannot be offered or if curative treatment is declined. Rationale Lymphomas are a diverse group of malignancies entailing widely divergent natural histories, outcomes and approaches to management. The evidence base for the management of lymphoma is rapidly changing; a detailed assessment is beyond the scope of this document. Results of therapy are likely to be optimal when it is delivered according to a formal written policy. It is important that policies are in line with those in use elsewhere in Australasia and worldwide. Substantial deviation should occur only in the context of a formal clinical trial. Chemotherapeutic agents include other systemic therapies, such as biological agents and cytokines. Chemotherapeutic agents are potentially dangerous; fatalities have occurred due to their inappropriate administration. This particularly applies to systemic therapy given via the intrathecal route. It is therefore essential that systemic therapy is provided by trained specialist staff in a safe environment with appropriate facilities. A diagnosis of lymphoma and its subsequent treatment can have a devastating impact on the quality of a person’s life, as well as on the lives of their family/whānau and other carers. Patients and their family/whānau should expect to be offered optimal symptom control and psychological, social and spiritual support. Most patients will experience a significant symptom burden during their cancer journey. The role of palliative care in patients with lymphoma is important. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 21 Good practice points General 7.1 Treatment plans follow formal policies and protocols as much as possible. Total care plans are individualised, taking into account a patient’s needs and physical, social, cultural, emotional, psychological and spiritual preferences. Systemic therapy 7.2 Treatment is evidence based and adheres to local, national or international guidelines (eg, NCCN Guidelines and guidelines published by the Lymphoma Network New Zealand and the Cancer Institute of New South Wales). 7.3 Treatment protocols include: regimens and their indications drug doses and scheduling radiation therapy protocol pre- and post-treatment investigations dose modifications. Radiation therapy 7.4 Where combined modality treatment is planned, pre-treatment imaging encompasses all sites of disease, to facilitate radiotherapy planning. Where this is not possible, early involvement of a radiation oncologist is required. 7.5 Treatment is delivered in accordance with the Radiation Oncology Prioritisation Guidelines (Ministry of Health 2011b). 7.6 Radiotherapy commences four–six weeks after completion of systemic therapy when delivered as part of a combined modality protocol. Surgery 22 7.7 The role of surgery in the management of lymphoma is generally limited to obtaining tissue for diagnostic purposes. 7.8 Patients, and particularly Māori and Pacific patients, are given the option of retaining tissue postoperatively (NZGG 2009). Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional Stem cell transplantation 7.10 High-dose chemotherapy/systemic therapy or stem cell transplantation are only delivered: by specialists with appropriate training in a centre with appropriate experience and resources following approval from a regional stem cell transplant advisory committee. Palliative care 7.11 Palliative care is available to all patients diagnosed with lymphomas based on need and independent of current health status, age, cultural background or geography. 7.12 Palliative care is given in accordance with Hospice New Zealand’s Standards for Palliative Care (2012) and a recognised end-of-life-care pathway. 7.13 A written care plan and a common electronic management system are recommended. 7.14 Patients and their families/whānau are offered palliative care options and information in plain language that is targeted to their particular needs, and this is incorporated into their care plans. Monitoring requirements MR7A Audit records of proposed plans of care, onward referrals and follow-up responsibilities recorded at MDT reviews and in patients’ notes. MR7B Audit patient satisfaction surveys. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 23 8 Follow-up and Surveillance Standard 8.1 Follow-up plans include clinical review and potential late toxicities by appropriate members of the MDT, working in conjunction with the patient, their family/whānau and their GP. Standard 8.2 Women under the age of 40 treated with radiotherapy for lymphoma undergo individualised breast screening if breast tissue was included in their radiotherapy treatment. Rationale Relapse is rarely detected by routine scanning of asymptomatic patients. Follow-up for lymphoma patients should screen for clinical signs of relapse and late toxicities, including second cancers. It is important that patients maintain a strong relationship with their GP, as many are vulnerable to the premature onset of common conditions associated with aging, such as diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia. The risk posed by second malignancies may be reduced by lifestyle modification and/or screening. Good practice points 8.1 A follow-up schedule is formulated for individual patients that covers frequency of visits, tests required and designated services, with a nominated point of contact in the case of clinical concerns. 8.2 Patients are given the opportunity to review their social circumstances with a relevant health professional, to support advance care planning. 8.3 In order to promote healthy living, patients are encouraged to discuss Green Prescriptions2 with their GP. Patients with aggressive lymphoma 8.4 For Hodgkin and high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma, follow-up care should include the following: First two–three years after therapy: 2 24 clinical assessment three–four-monthly imaging studies as clinically indicated; once a post-treatment baseline is established there is no requirement to undertake ‘routine’ surveillance CT or PET-CT scanning A Green Prescription (GRx) is a health professional’s written advice to a patient to be physically active, as part of the patient’s health management. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional Three–five years after therapy: six-monthly clinical assessment by the patient’s GP in a primary-care setting, particularly looking for recurrent lymphadenopathy or the onset of B symptoms investigations as clinically indicated late-effects-specific screening, such as: – endocrine surveillance – thyroid, fertility – cardiac assessment – after radiation to the chest – osteoporosis – premature menopause, steroid use – myelodysplasia – renal function. Patients with low-grade lymphomas 8.5 Follow-up care is individualised to assess symptomatic progression. This will depend on the age of the patient, the extent and biology of the disease, and prior therapy. Patients who have previously received high-dose therapy/a blood stem cell transplant 8.6 Long-term specialist follow-up care is required to screen for late effects. Monitoring requirements MR8A Audit written follow-up information provided following agreed surveillance protocols. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 25 9 Clinical Performance Monitoring and Research Standard 9.1 Data relating to lymphoma beyond the fields required by the Cancer Registry, including treatment data, are reported to existing and planned national repositories using nationally agreed data set fields. Standard 9.2 Patients with lymphoma are offered the opportunity to participate in research projects and clinical trials where these are available. Rationale There is currently no national cancer database other than the New Zealand Cancer Registry, which is a population-based register of all primary malignant tumours diagnosed in New Zealand. This is a significant impediment to advancing cancer care in this country. Cancer data-related projects are currently being undertaken or planned by the Ministry of Health, Cancer Control New Zealand and regional cancer networks. Good practice points 26 9.1 Patients are informed that their information is being recorded in a lymphoma database to help the MDT propose a treatment plan for them and to monitor and evaluate access to services. 9.2 Where data are collected, they are compiled in accordance with relevant National Cancer Core Data Definition Interim Standards. 9.3 Multidisciplinary teams are responsible for collecting and managing information in relation to patients with lymphoma. 9.4 Clinicians working with patients with lymphoma have access to the database, to help inform disease management. 9.5 Information concerning all clinical trials being conducted in New Zealand hospitals is made available to patients and clinicians. 9.6 Patients suitable for lymphoma trials being conducted in New Zealand are not prevented from enrolment due to geographic or other barriers. DHBs make every effort to facilitate entry of patients into trials where they are being conducted outside of patients’ DHB of residency. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional Monitoring requirements MR9A Provide evidence that patient data are collected in accordance with national protocols. MR9B Audit the data collection annually to ensure accuracy and compliance. MR9C Monitor the data collection (including, where possible, ‘did-not-attends’) by ethnicity. MR9D Provide evidence of the reporting of data sets to national data repositories (as available) at agreed frequencies. MR9E Ensure that MDMs provide documentation of all open trials/research projects, and numbers of patients entered per trial per year. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 27 Appendix 1: National Lymphoma Tumour Standards Working Group Membership Chair Dr Leanne Berkahn, Haematologist, Auckland DHB Members Dr Simon Allan, Director of Palliative Care, Arohanui Hospice Marj Allen, Consumer Representative Dr Kate Clarke, Medical Oncologist, Capital & Coast DHB Dr Jim Edwards, Medical Oncologist, Canterbury DHB Pru Etcheverry, Chief Executive Officer, Leukaemia and Blood Cancer New Zealand Dr Ross Henderson, Clinical Director of Haematology, Waitemata DHB Rosie Howard, Bone Marrow Transplant Clinical Nurse Specialist, Auckland DHB Dr Deborah Ingham, GP, Kelburn Surgery Lizzie Kent, Clinical Psychologist, Massey University Dr Allanah Kilfoyle, Haematologist, MidCentral DHB Dr Richard Lloyd, Pathologist, Auckland DHB Dr Alex Ng, Surgeon, Auckland DHB Dr Anna Nicholson, Radiation Oncologist, Capital & Coast DHB Toni Nicholson, Social Worker, MidCentral DHB Dr Humphrey Pullon, Haematologist, Waikato DHB Dr Jeremy Sharr, Radiologist, Christchurch Radiology Group Liz Sommers, Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Clinical Nurse Specialist, Capital & Coast DHB Stephanie Turner, Director of Māori Health, Wairarapa DHB Advisors and stakeholders Dr Bart Baker, Clinical Director of Haematology, MidCentral DHB Mary Birdsall, Medical Director, Fertility Associates Dr Liam Fernyhough, Haematologist, Canterbury DHB Dr Tony Goh, Radiologist, Canterbury DHB Dr Wendy Jar, Clinical Nurse Specialist, Canterbury DHB Phil Kerslake, Consumer Representative Anne Krishna, Clinical Nurse Specialist, Haematology, MidCentral DHB Sheldon Ngatai, Consumer Representative Catherine Oliver, Adult Haematology Pharmacist, Auckland DHB 28 Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional Appendix 2: Glossary Advance care planning A process of discussion and shared planning for future health care Allied health professional One of the following groups of health care workers: physiotherapists, occupational therapists, dietitians, orthoptists, paramedics, prosthetists/orthotists, radiation therapists, social workers and speech and language therapists Asymptomatic Without obvious signs or symptoms of disease. In early stages, cancer may develop and grow without producing symptoms Best practice A method or approach that is accepted by consensus to be the most effective way of doing something, in the circumstances; may or may not be based on evidence Biopsy Removal of a sample of tissue or cells from the body to assist in the diagnosis of a disease Cancer journey The individual and personal experience of a person with cancer throughout the course of their illness Cancer Networks Cancer Networks were formed in response to national policy to drive change and improve cancer services for the population in specific areas. There are four regional networks: Northern, Midland, Central and Southern Cancer service pathway The cumulative cancer-specific services that a person with cancer uses during the course of their experience with cancer Care coordination Entails the organising and planning of cancer care, who patients and family/whānau see, when they see them and how this can be made as easy as possible. It may also include identifying who patients and family/whānau need to help them on the cancer pathway Chemotherapy The use of drugs that kill cancer cells, or prevent or slow their growth (also see systemic therapy) Clinical trial An experiment for a new treatment Computed tomography (CT) A medical imaging technique using X-rays to create crosssectional slices through the body part being examined Confirmed diagnosis (used in FCT indicators) The preferred basis of a confirmed cancer diagnosis is pathological, noting that for a small number of patients cancer diagnosis will be based on diagnostic imaging findings Consumer A user of services Curative Aiming to cure a disease Cytogenetics The study of chromosomes and chromosomal abnormalities Decision to treat (used in FCT indicators) A decision to begin a patient’s treatment plan or other management plan, following discussion between the patient and treating clinician Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 29 30 DHB District Health Board End-of-life care The provision of supportive and palliative care in response to the assessed needs of the patient and family/whānau during the end-of-life phase Excision The removal of tissue by surgery Family/whānau Can include extended family/whānau, partners, friends, advocates, guardians and other representatives Faster Cancer Treatment (FCT) A Ministry of Health programme that will improve services by standardising care pathways and timeliness of services for cancer patients throughout New Zealand Faster Cancer Treatment indicators Measures of cancer care collected through DHB reporting of timeframes within which patients with a high suspicion of cancer access services. The indicators are internationally established and provide a goal for DHBs to achieve over time Fine needle aspiration cytology The use of a fine needle to biopsy a tumour or lymph node to obtain cells for cytological confirmation of diagnosis First specialist assessment (FSA) Face-to-face contact (including telemedicine) between a patient and a registered medical practitioner or nurse practitioner for the purposes of first assessment for their condition for that specialty First treatment (used in FCT indicators) The treatment or other management that attempts to begin a patient’s first treatment, including palliative care Haematologist A doctor who specialises in the diagnosis and treatment of all blood diseases, including malignant blood diseases such as leukaemia, lymphoma and myeloma Health equality/equity Absence of unnecessary, avoidable and unjust differences in health (Ministry of Health 2002) Health inequality/ inequity Differences in health that are unnecessary, avoidable or unjust (Ministry of Health 2002) High-grade cancer A cancer that tends to grow more aggressively, be more malignant and have the least resemblance to normal cells High suspicion of cancer (used in FCT indicators) Where a patient presents with clinical features typical of cancer, or has less typical signs and symptoms but the clinician suspects that there is a high probability of cancer Histological Relating to the study of cells and tissue on the microscopic level Holistic Looking at the whole system rather than just concentrating on individual components Hospice Hospice is not only a building; it is a philosophy of care. The goal of hospice care is to help people with life-limiting and lifethreatening conditions make the most of their lives by providing high-quality palliative and supportive care Lesion An area of abnormal tissue Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional Lymphadenopathy Disease or swelling of the lymph nodes Malignant Cancerous. Malignant tumours can invade and destroy nearby tissue and spread to other parts of the body Medical oncologist A doctor who treats cancer patients through the use of chemotherapy, and, for some tumours, immunotherapy Medical oncology The specialist treatment of cancer patients through the use of chemotherapy and, for some tumours, immunotherapy Metastases Cancerous tumours in any part of the body that have spread from the original (primary) origin. Also known as ‘secondaries’ Morbidity The state of being diseased Mortality Either (a) the condition of being subject to death or (b) the death rate, which reflects the number of deaths per unit of population in any specific region, age group, disease or other classification, usually expressed as deaths per 1000, 10,000 or 100,000 Multidisciplinary meeting (MDM) A deliberate, regular, face-to-face meeting (which may be through videoconference) to facilitate prospective multidisciplinary discussion of options for patients’ treatment and care by a range of health professionals who are experts in different specialties. ‘Prospective’ treatment and care planning refers to making recommendations in real time, with an initial focus on the patient’s primary treatment. Multidisciplinary meetings entail a holistic approach to the treatment and care of patients Multidisciplinary team (MDT) A group of specialists in a given disease area. The MDT meets regularly to plan aspects of patient treatment. Individual patient cases might be discussed at an MDM, to best plan approach to treatments National Health Index number A unique identifier for New Zealand health care users Oncology The study of the biological, physical and chemical features of cancers, and of the causes and treatment of cancers Palliative Anything that serves to alleviate symptoms due to the underlying cancer but is not expected to cure it Palliative care Active, holistic care of patients with advanced, progressive illness that may no longer be curable. The aim is to achieve the best quality of life for patients and their families/whānau. Many aspects of palliative care are also applicable in earlier stages of the cancer journey in association with other treatments Pathologist A doctor who examines cells and identifies them. The pathologist can tell where a cell comes from in the body and whether it is normal or a cancer cell. If it is a cancer cell, the pathologist can often tell what type of body cell the cancer developed from. In a hospital practically all the diagnostic tests performed with material removed from the body are evaluated or performed by a pathologist Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 31 32 Pathology A branch of medicine concerned with disease, especially its structure and its functional effects on the body Patient pathway The individual and personal experience of a person with cancer throughout the course of their illness; the patient journey Positron emission tomography (PET) A highly specialised imaging technique using a radioactive tracer to produce a computerised image of body tissues to find any abnormalities. PET scans are sometimes used to help diagnose cancer and investigate a tumour’s response to treatment Positron emission tomography and computed tomography (PET-CT) An advanced imaging technique combining an injected material (18 Fluorine) which is taken up by cancer cells and a CT scan Primary care Primary-level health services provided by a range of health workers, including GPs and nurses Radiologist A doctor who specialises in creating and interpreting pictures of areas inside the body using X-rays and other specialised imaging techniques. An interventional radiologist specialises in the use of imaging techniques for treatment; for example catheter insertion for abscess drainage Radiology The use of radiation (such as X-rays, ultrasound and magnetic resonance) to create images of the body for diagnosis Radiotherapy (radiation treatment) The use of ionising radiation, usually X-rays or gamma rays, to kill cancer cells and treat tumours Recurrence The return, reappearance or metastasis of cancer (of the same histology) after a disease-free period Referred urgently (used in FCT indicators) Describes urgent referral of a patient to a specialist because her or she presents with clinical features indicating high suspicion of cancer Stage The extent of a cancer, especially whether the disease has spread from the original site to other parts of the body Staging Usually refers to the Tumour, node, metastasis system for grading tumours by the American Joint Committee on Cancer Supportive care Supportive care helps a patient and their family/whānau to cope with their condition and treatment – from pre-diagnosis through the process of diagnosis and treatment to cure, continuing illness or death, and into bereavement. It helps the patient to maximise the benefits of treatment and to live as well as possible with the effects of the disease Synoptic report A standardised proforma for reporting of cancer Systemic therapy Treatment using substances that travel through the bloodstream, reaching and affecting cells all over the body Tertiary Third level. Relating to medical treatment provided at a specialist institution Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional Toxicity The extent of the undesirable and harmful side-effects of a drug Tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) A staging system that describes the extent of cancer Ultrasound A non-invasive technique using ultrasound waves (highfrequency vibrations beyond the range of audible sound) to form an image Whānau Māori term for a person’s immediate family or extended family group. In the modern context, sometimes used to include people without kinship ties Whānau Ora An inclusive interagency approach to providing health and social services to build the capacity of New Zealand families. It empowers family/whānau as a whole, rather than focusing separately on individual family members X-ray A photographic or digital image of the internal organs or bones produced by the use of ionising radiation Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 33 Appendix 3: The Lymphoma Patient Pathway 34 Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional Appendix 4: Recommended GP Referral Form Surname: .......................................................................................... Given names:.................................................................................... GP NEW PATIENT REFERRAL FORM LYMPHOMA DOB: ........................................... Sex: .......................................... NHI: ................................................................................................... Address: ............................................................................................ .......................................................................................................... Contact details: ................................................................................. Referring clinician details: Name: ........................................................ Phone: ........................ Fax: ............................ Date of referral: ....................................................................................................................... Patient details: ......................................................................................................................... Presentation: ........................................................................................................................... ................................................................................................................................................ B symptoms: Fever Weight loss Night sweats Examination findings Splenomegaly Lymph nodes Hepatomegaly Other ............................................................ Significant co-morbidities ........................................................................................................ Relevant psychosocial issues ................................................................................................. Current medications: ............................................................................................................... Allergies:.................................................................................................................................. Work-up: investigations and procedures Please provide reports of any investigations undertaken when submitting this form: FBC LDH LFT, creatinine CXR FNA CT scan Other procedures Yes No Pending Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 35 Urgency of referral Immediate review required (one to two days) Make phone contact Patient critically unwell, tumour causing compression symptoms, suspected Burkitt lymphoma Urgent (within two weeks) Suspected Hodgkin or aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma Semi-urgent (within four weeks) (suspected indolent lymphoma) 36 Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional Appendix 5: References Development of the lymphoma standards was informed by key national and international documents. Those documents that most directly influenced the development of the standards are listed below. British Committee for Standards in Haematology. 2011. Guidelines on the Investigation and Management of Follicular Lymphoma. London: British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network. 2007. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Lymphoma. Sydney: Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network. Central Cancer Network. 2010. Imaging Guidelines in Cancer Management. Palmerston North: Central Cancer Network. Department of Health, Government of South Australia. 2010. South Australian Lymphoma Pathway: Optimising outcomes for all South Australians diagnosed with lymphoma. Adelaide: Department of Health, Government of South Australia. Ministry of Health. 2003. The New Zealand Cancer Control Strategy. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health. 2005. The New Zealand Cancer Control Strategy Action Plan 2005–2010. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health. 2010. Guidance for Improving Supportive Care for Adults with Cancer in New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health. 2011b. Radiation Oncology Prioritisation Guidelines. URL: www.midlandcancernetwork.org.nz/file/fileid/44264 (accessed 6 August 2013). Ministry of Health. 2011c. Targeting Shorter Waits for Cancer Treatment. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health. 2012b. Guidance for Implementing High-Quality Multidisciplinary Meetings: Achieving best practice cancer care. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health. 2012c. Medical Oncology Prioritisation Criteria. URL: www.nsfl.health.govt.nz/apps/nsfl.nsf/pagesmh/401 (accessed 6 August 2013). Ministry of Health. 2013. Faster Cancer Treatment Programme. URL: www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/cancer-programme/faster-cancertreatment-project (accessed 6 August 2013). NICE. 2003. Guidance on Cancer Services: Improving Outcomes in Haematological Cancers. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Northern Cancer Network. 2011. Regional Cancer Care Coordination Model Project. Auckland: Northern Cancer Network. RCPA. 2010. Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissue Structured Reporting Protocol. Sydney: Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 37 Woodley D. 2012. Implementing the Faster Cancer Treatment Indicators – Supplementary Information. (Letter to DHB Chief Executive Officers and General Managers Planning and Funding, cc DHB Chief Information Officers, Chief Operating Officers and Regional Cancer Network Managers.) URL: www.midlandcancernetwork.org.nz/file/fileid/44227 (accessed 6 August 2013). Introduction Ministry of Health. 2002. Reducing Inequalities in Health. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health. 2010. Guidance for Improving Supportive Care for Adults with Cancer in New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health. 2012a. Cancer: New registrations and deaths 2009. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health. 2012d. Rauemi Atawhai: A guide to developing health education resources in New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health. National Lung Cancer Working Group. 2011. Standards of Service Provision for Lung Cancer Patients in New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Timely access to services Ministry of Health. 2011b. Radiation Oncology Prioritisation Guidelines. URL: www.midlandcancernetwork.org.nz/file/fileid/44264 (accessed 6 August 2013). Ministry of Health. 2012c. Medical Oncology Prioritisation Criteria. URL: www.nsfl.health.govt.nz/apps/nsfl.nsf/pagesmh/401 (accessed 6 August 2013). Woodley D. 2012. Implementing the Faster Cancer Treatment Indicators – Supplementary Information. (Letter to DHB Chief Executive Officers and General Managers Planning and Funding, cc DHB Chief Information Officers, Chief Operating Officers and Regional Cancer Network Managers.) URL: www.midlandcancernetwork.org.nz/file/fileid/44227 (accessed 6 August 2013). Referral and communication Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network. 2007. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Lymphoma. Sydney: Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network. Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network. 2007. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Lymphoma: A guide for general practitioners. Sydney: Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network. Department of Health, Government of South Australia. 2010. South Australian Lymphoma Pathway: Optimising outcomes for all South Australians diagnosed with lymphoma. Adelaide: Department of Health, Government of South Australia. Ministry of Health. 2009. About Elective Services Patient Flow Indicators. URL: www.health.govt.nz/our-work/hospitals-and-specialist-care/elective-services/electiveservices-and-how-dhbs-are-performing/about-elective-services-patient-flow-indicators (accessed 16 August 2013). Ministry of Health. 2012d. Rauemi Atawhai: A guide to developing health education resources in New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health. 38 Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional NICE. 2005. Referral Guidelines for Suspected Cancer. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence. NZGG. 2009. Suspected Cancer in Primary Care: Guidelines for investigation, referral and reducing ethnic disparities. Wellington: New Zealand Guidelines Group. Investigation, diagnosis and staging Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network. 2007. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Lymphoma. Sydney: Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network. Central Cancer Network. 2010. Imaging Guidelines in Cancer Management. Palmerston North: Central Cancer Network. Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. 2007. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 25(5): 579–86. Department of Health, Government of South Australia. 2010. South Australian Lymphoma Pathway: Optimising outcomes for all South Australians diagnosed with lymphoma. Adelaide: Department of Health, Government of South Australia. NICE. 2003. Guidance on Cancer Services: Improving outcomes in haematological cancers. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence. NZGG. 2009. Suspected Cancer in Primary Care: Guidelines for investigation, referral and reducing ethnic disparities. Wellington: New Zealand Guidelines Group. RCPA. 2010. Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissue Structured Reporting Protocol. Sydney: Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia. RCR. Date unknown. Cancer Imaging and Reporting Guidelines. London: Royal College of Radiologists (member access only). Multidisciplinary care Ministry of Health. 2010. Guidance for Improving Supportive Care for Adults with Cancer in New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health. 2012b. Guidance for Implementing High-Quality Multidisciplinary Meetings: Achieving best practice cancer care. Wellington: Ministry of Health. NHS National Cancer Action Team. 2010. The Characteristics of an Effective Multidisciplinary Team. London: NHS National Cancer Action Team. Supportive care Ministry of Health. 2006. The National Travel Assistance Scheme: Your guide for claiming travel assistance: Brochure. URL: www.health.govt.nz/publication/national-travel-assistancescheme-your-guide-claiming-travel-assistance-brochure (accessed 14 August 2013). Ministry of Health. 2010. Guidance for Improving Supportive Care for Adults with Cancer in New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health. 2012d. Rauemi Atawhai: A guide to developing health education resources in New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health. National Lung Cancer Working Group. 2011. Standards of Service Provision for Lung Cancer Patients in New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 39 NHS Wales. 2005. National Standards for Haemotological Cancer Services. Cardiff: NHS Wales. NICE. 2004. Guidance on Cancer Services: Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Northern Cancer Network. 2011. Regional Cancer Care Coordination Model Project. Auckland: Northern Cancer Network. Care coordination Baken DM, Woolley C. 2011. Validation of the Distress Thermometer, Impact Thermometer and combinations of these in screening for distress. Psychooncology 20(6): 609–14. Ministry of Health. 2010. Guidance for Improving Supportive Care for Adults with Cancer in New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health. 2012d. Rauemi Atawhai: A guide to developing health education resources in New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health. National Lung Cancer Working Group. 2011. Standards of Service Provision for Lung Cancer Patients in New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health. NHS Wales. 2005. National Standards for Haemotological Cancer Services. Cardiff: NHS Wales. NICE. 2004. Guidance on Cancer Services: Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Northern Cancer Network. 2011. Regional Cancer Care Coordination Model Project. Auckland: Northern Cancer Network. Treatment American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Guidelines, Policy Statements and Reviews. URL: www.asbmt.org/displaycommon.cfm?an=4 (accessed 16 August 2013). BAHNO. 2009. BAHNO Standards 2009. London: British Association of Head and Neck Oncologists. Hospice New Zealand. 2012. Standards for Palliative Care: Quality review programme and guide. Wellington: Hospice New Zealand. Liverpool Care Pathway. 2009. New Zealand Integrated Care Pathway for the Dying Patient. http://lcpnz.org.nz/pages/home (accessed 16 August 2013). Ministry of Health. 2011a. Bone Marrow Transplant Services in New Zealand for Adults – Service Improvement Plan. Wellington: Ministry of Health. National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. Adult Cancer Treatment Summaries. URL: www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/adulttreatment (accessed 16 August 2013). NCCN. 2012. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) – Palliative Care. Fort Washington: National Comprehensive Cancer Network (member access only). NICE. 2004. Guidance on Cancer Services: Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence. 40 Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand Provisional NZGG. 2009. Suspected Cancer in Primary Care: Guidelines for investigation, referral and reducing ethnic disparities. Wellington: New Zealand Guidelines Group. Palliative Care Australia. 2005. Standards for Providing Quality Palliative Care for all Australians. Canberra: Palliative Care Australia. Follow-up and surveillance Armitage JO. 2012. Who Benefits from Surveillance Imaging? Journal of Clinical Oncology 30(21): 2579–80. Department of Health, Government of South Australia. 2010. South Australian Lymphoma Pathway: Optimising outcomes for all South Australians diagnosed with lymphoma. Adelaide: Department of Health, Government of South Australia. Eichenauer A, Engert A, Dreyling M, et al. 2011. Hodgkin’s lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology 22(Suppl 6): vi55–8. Gerlinger M, Rohatiner AZ, Matthews J, et al. 2010. Surveillance investigations after highdose therapy with stem cell rescue for recurrent follicular lymphoma have no impact on management. Haematologica 95(7): 1130–5. Mauch P, Ng A, Aleman B, et al. 2005. Report from the Rockefeller Foundation sponsored International Workshop on reducing mortality and improving quality of life in long-term survivors of Hodgkin disease. European Journal of Haematology 75 Suppl 66: 68–76. NCCN. 2012. Guidelines Version 2.2012: Hodgkin lymphoma. Fort Washington: National Comprehensive Cancer Network (member access only). Royal Australasian and New Zealand College of Radiologists. 2010. Breast Cancer and Late Effects Following Radiotherapy and Systemic Therapy for Hodgkin Lymphoma. Sydney: Royal Australasian and New Zealand College of Radiologists. Tilly H, Dreyling M, et al. 2010. Diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: EMSO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology 21(Suppl 5): v172–4. Wagner-Johnston ND, Bartlett NL. 2011. Role of routine imaging in lymphoma. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 9(5): 575–84. Clinical performance monitoring and research IT Health Board. 2011. National Cancer Core Data Definitions, Interim Standard, HISO 10038.3. Wellington: IT Health Board. Appendices Ministry of Health. 2002. Reducing Inequalities in Health. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Standards of Service Provision for Lymphoma Patients in New Zealand – Provisional 41