Bone Loading Exercise Recommendations for Prevention

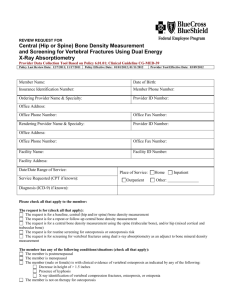

advertisement

Bone Loading Exercise Recommendations for Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis Written on Behalf of the IOF Committee of Scientific Advisors by Michael Pfeifer and Helmut W. Minne, Gustav Pommer Institute of Clinical Osteology and German Academy of the Osteological and Rheumatological Sciences Contents: Foreword Introduction and definitions Recommendations for children and adolescents Recommendations for young adults and pre-menopausal women Recommendations for postmenopausal women Recommendations for men Recommended exercise for fall prevention Recommended exercise for patients with osteoporosis Foreword This report, provided on the health professionals section of the IOF website, outlines specific exercise programs which have been shown in scientific studies to improve or maintain bone health in men, women and children and at various life stages. Please note that many of the regimens and images shown in this article derive from professionally supervised exercise programs, are not appropriate for everyone, and should not be carried out without professional supervision. Page Top Introduction and Definitions Physical activity is an umbrella term defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure above the basal level [1]. The dimensions of physical activity – frequency, intensity, time, and type (FITT) – each have an effect on the health outcome. Studies suggest that the type of physical activity carried out is by far the most important dimension that affects bone [2]. Exercise represents a sub-category of physical activity that is planned, structured, repetitive and purposeful with the aim of improving or maintaining one or more aspects of physical fitness [3]. Exercise may be carried out for pleasure or to maintain health. Targeted Bone Loading describes force-generating activities that stimulate a specific bone or bone region beyond the level provided by daily activities. An activity may provide bone loading at one site, but not at another. For instance jumping involves lower limb bone loading, but not upper limb. Although all exercise commonly involves some form of loading through muscles and joints, some forms of exercise do not involve targeted bone loading. While virtually all physical activity reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease, swimming and cycling, for example, will rarely augment bone mineral density (BMD) [4]. With increasing age, however, the emphasis of exercise should switch gradually from bone loading to muscle loading in order to improve parameters of muscle function such as strength and coordination. This also holds true for patients with advanced osteoporosis (characterized by multiple fractures and severely reduced bone mineral density) to help them avoid further fractures, prevent falls and to facilitate daily activities [5]. The following recommendations for exercise programs to improve or maintain bone health in various age groups are evidence-based. Page Top Recommendations for children and adolescents This section focuses on children from eight years old through to adolescence and young adulthood. Data drawn from different studies with children in these age groups have been used to develop the following recommendations [6]: Make a lifelong commitment to physical activity and exercise. In terms of bone health, weight-bearing activities such as basketball, volleyball and gymnastics are more effective than weight-supported activities such as swimming and cycling. Intense daily activity is more effective than prolonged activity carried out infrequently. Perform activities that will increase muscle strength, such as running, hopping, or skipping games. Select activities that work all muscle groups like gymnastics. Avoid immobilization and perform short weight-bearing movements if confined to bed. Eat a well-balanced diet that is rich in calcium (milk instead of soft drinks) and protein to promote normal growth and puberty as well as regular menses for girls. The following exercise program from Melbourne, Australia, demonstrated significant increases in BMD in 9- to 10-year old children at both the lumbar spine and the proximal femur. In addition to regular physical education at school, this program incorporated extra classes for the children which resulted in an additional increase in BMD of 4% at the spine and 2% at the proximal femur [7, 8]. Frequency: Three times per week Intensity: High impact Time: 30 minutes of physical activity after school Type: 1. Aerobic workouts: Aerobics, soccer, step aerobics, skipping, ball games, modern dance and weight training 2. Circuit training: 20-minute weight-bearing, strength-building circuit consisting of 10 exercises designed to load the biceps, triceps, pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, trunk, deltoids, rectus abdominis, quadriceps femoris, hamstrings, gastrocnemius, and soleus Approximately 1 minute per station One set of 10 repetitions progressing to 3 sets of 10 over time These recommendations are based on strong scientific evidence suggesting that weight-bearing physical activity plays a key role during the normal growth and development of a healthy skeleton. High-intensity exercise of short duration appears to elicit the greatest bone density increase in the growing skeleton. This information is especially important to parents, teachers and health authorities that are responsible for school curricula. A sedentary lifestyle, rather than an excessively active one, is more likely to be the risk faced by most children today [9]. Page Top Recommendations for young adults and premenopausal women After puberty, bone mineral density (BMD) is not easily augmented. The main role of exercise in young adults and pre-menopausal women, therefore, is to maintain BMD rather than to increase it. Nevertheless, high-intensity exercise can lead to modest bone accrual in targeted areas. Even small increases in bone mineral may significantly reduce the risk of fracture in later life. The following exercise plan designed by Heinonen and colleagues in Tampere, Finland, has been shown to increase lumbar spine and femoral neck BMD in 35- to 45-year old Finnish women by approximately 2% [10]: Activity Duration Warm-up 15 min. High-impact jumps* 20 min. Stretching and non-impact activities 15 min. Cool-down 10 min. *High-impact jump training consisted of an aerobic jump program alternated weekly with a step program. Sessions were performed three times per week over an 18-month period and the height of the jumps increased progressively from 10 to 25 cm, while the number of jumps per session decreased from 200 to 100. Friedlander and colleagues described a resistance-training protocol that used three different classes per week over two years to augment BMD at the lumbar spine (approximately 5%) and femoral neck (approximately 3%) [11]: Class 1: Participants alternate (every 12 min.) between exercise stations and high-impact aerobic activities. Exercise stations consisted of push-ups, sit-ups, arm-curls with dumbbells, and presses with barbells. Class 2: Moderate weights (dumbbells between 3 and 6 kg and barbells between 8 and 18 kg) were used to exercise the gluteus maximus, erector spinae, and shoulder girdle muscles. Lifts were started from ground level to shoulder height. Class 3: A vigorous, high-impact aerobic workout was performed during which the heart rate was maintained at between 70 to 85% of maximum performance, calculated as 220 minus age. In 2002, Mehrsheed Sinaki and colleagues published the first randomized prospective study demonstrating that exercise in premenopausal women may not only increase BMD at the lumbar spine but also decrease the risk of vertebral fractures [12]. They found that progressive, resistive back strengthening exercise performed 5 days per week over two years reduced the risk for vertebral fractures 10 years later. Fig.1 shows a back-strengthening exercise to increase back extensor strength to maintain BMD at the lumbar spine and to decrease the risk of vertebral fractures. Page Top Recommendations for postmenopausal women Besides maintaining bone strength, the main goal of exercise therapy in postmenopausal women is to increase muscle mass in order to improve parameters of muscle function such as balance and strength, which are both important risk factors for falls and - independent of bone density – risk factors for bone fractures. Kemmler and colleagues from Erlangen, Germany, described an exercise program which is effective in maintaining bone density and skeletal health in postmenopausal women between 48 and 60 years of age with low bone mass [13]. The program consists of four sessions per week with two group sessions lasting 60 to 70 minutes each and two home training sessions of 25 minutes each. Warm up/Endurance sequence For the first three months or so, gradually increase walking and running to 20 minutes to get patients accustomed to higher impact rates. Running games can be added to promote unusual strain distributions under weight-bearing conditions. After three months, 10 minutes of low to high impact aerobic exercise with an increasing amount of high-impact aerobic exercise can conclude the sequence (Fig.2). Fig.2: Aerobic exercise during warm-up and endurance sequence Jumping sequence The jumping sequence is integrated after six months of training, by which time a certain level of training adaptation had been achieved. For patients who have suffered vertebral fractures, “jumping” should be substituted by “walking” in order to reduce the impact on the spine. After an introductory rope-skipping phase, more complicated jumps (e.g. closed leg jumps) can be attempted. Strength-training sequence This consists of two sessions, one using resistance machines and the other isometric exercises, elastic belts, dumbbells, and weighted vests. On the hydraulic resistance machines specifically designed for seated rows, back extension, abdominal flexion or bench press, 13 exercises are performed that use all the main muscle groups (Figs.3-12). Exercise intensity should be increased slowly. In the first three months, two sets of 20 repetitions at 50% of the “one-repetition maximum” (1RM) are performed. The 1RM is the maximum mass of a free weight or other resistance that can be moved by a muscle group through the full range of motion with good form one time only. The 1RM should be determined very cautiously in order to avoid vertebral fractures, especially in patients with low bone mass. After three months, two sets of 15 repetitions at 60% of 1RM and after five months two sets of 15 repetitions at 65% of 1RM are performed. After seven months of training, the intensity should be increased to 70%-80% of 1RM. The second strength-training session consists of 12 to 15 different isometric exercises* predominantly dedicated to the trunk and legs. In addition, three different belt exercises of 15 to 20 repetitions are applied to the upper trunk. After the first seven months, belt training is replaced by exercises using dumbbells (Fig.8) and a weighted vest (Fig.9). Fig.3: Hamstring curl during strength training sequence Figs.4 + 5: Hip abduction (left) and hip adduction (right) during strength training Fig.6: Leg extension during strength training sequence Fig.7: Leg press during strength training sequence Fig.8: Arm curl using dumbbells during strength-training sequence Fig.9: Arm curl using dumbbell or “one-arm rowing” during strength training Fig.10: Bent knee dead lifts with weighted vest during strength training sequence Fig.11: Triceps extension (using pulley) or latissimus pulldown during strength-training sequence Fig.12: Hyper-extension of the back to improve back extensor strength during strength-training sequence Flexibility-training sequence This sequence is performed before and after the strength-training sessions and during the rest periods. The stretching program consists of 10 exercises for all main muscle groups. Two sets of passive stretching exercises lasting over 30 seconds are performed. Additional home-training sessions Isometric, belt, and stretching exercises should also be performed at home twice weekly for 25 minutes. An additional rope-skipping program can be introduced 20 weeks after the start of the training program. * Isometric exercise involves tensing a muscle and holding the position while maintaining tension (especially helpful to people recovering from injuries that limit range of motion). Page Top Recommendations for men Fewer studies of the effect of exercise have been conducted in men than women, but it appears that the skeleton responds similarly in both sexes. In men, high-impact training and strength-training produce increases in BMD. In addition, a prospective study showed a 60% reduction in hipfracture rates in men who were physically very active compared with those who were not [14]. A study in 23- to 31-year-old Japanese men found that the following protocol (Table 1) led to changes in bone markers that suggested bone formation was occurring without an increase in bone resorption. In the four-month study, total body and regional BMD did not change [15]. Table 1: Exercise prescription in young men that led to increase in biomarkers of bone formation without evidence of increased bone resorption Type of Exercise Intensity of exercise Time (Frequency in times/week) 1RM % of 1RM Repetitions and sets Leg extension (2) 30 kg 60-80% 10 3 Leg curl (2) 15 kg 60-80% 10 3 Bench press (3) 70 kg 60-80% 10 3 Sit-up (3) 22 kg 60-80% 10 3 Back extension (3) 15 kg 60-80% 10 3 Latissimus pull-down (1) 45 kg 60-80% 10 3 Arm curl (1) 20 kg 60-80% 10 3 Half squat (1) 70 kg 60-80% 10 3 Free weights were used except for leg extensions, leg curls, bench presses, and latissimus pull-downs, which were all done on a machine (see Figs.3-7, 11+12) Page Top Recommended exercise for fall prevention Falls and related fractures are a major health problem for older individuals and for society [16]. Changes in sensory and musculoskeletal structure and function among older adults puts them at increased risk of falls and injuries. Many intrinsic and external risk factors for falls have been identified. Exercise can modify the intrinsic fall risk factors and thus prevent falls in older adults [16]. Some of the external risk factors for falls may be modified by home safety inspections [17]. In a randomized prospective study in women with a mean age of 80 years, Campbell and colleagues demonstrated the efficacy of lower limb strength and balance training in reducing falls. Subjects in the intervention group received four home visits from a physiotherapist and performed individually tailored exercises three times per week, each session lasting more than 30 minutes, and were encouraged to take frequent walks. After one year, the mean number of falls in the intervention group was 0.87 compared to 1.34 in the control group, which corresponds to a reduction in the number of falls of 35% [18]. After the first year, these women were followed up for another 2 years and the relative risk for falls for the exercise group at two years was 0.69 (95% confidence interval 0.49-0.97) compared with controls [19]. Fig.13: The Posturomed has been shown to be an excellent training device for balance and coordination Another form of exercise which has been shown to reduce the risk of falls is Tai Chi. Wolf and colleagues compared Tai Chi performed for 15 minutes twice daily at home over 4 months in a group of 200 women with a mean age of 80 years against a control group participating in education sessions once a week. At the end of the study, subjects who performed Tai Chi had a 47% lower risk for falls compared to the control group [20]. Fig.14: Daily performance of Tai Chi Chun may reduce the risk for falls by half and may retard loss of BMD in postmenopausal women [21]. Page Top Recommended exercises for patients with osteoporosis An exercise program for people with osteoporosis should specifically target posture, balance, gait, coordination, and hip and trunk stabilization rather than general aerobic fitness. A typical class for relatively pain-free patients should consist of a warm-up, a workout, and a relaxation component. Warm-up: The general 10- to 15-minute warm-up may be done to music and starts with gentle range of motion exercises for the major joints, which are performed either seated or standing. The warm-up may end with walking and simple dance steps in order to achieve a heart rate of between 110 and 125 beats per minute. Workout: The workout may consist of strengthening and stretching exercises to improve posture by combating medially rotated shoulders, chin protrusion, thoracic kyphosis, and loss of lumbar lordosis. Exercises to improve balance and coordination may progress from heel raises and toe pulls to more challenging tandem walks and obstacle courses. Relaxation: The last 5 to 10 minutes of the class may be devoted to relaxation techniques such as deep breathing, progressive muscle tensing and relaxing, and perhaps visualizations to a background of soft music and/or nature sounds. In a study that investigated the efficacy of such a program carried out by a Canadian group from Vancouver in women with osteoporosis aged 65 to 75 years, the program resulted in an increased ability to undertake daily activities, decreased back pain, increased general health, and decreased risk of falling, and no patient suffered any exercise-related injuries [22]. Fig.15: Balance and coordination training during warm-up sequence Fig.16: Supervised posture training, walking and balance on different surfaces Fig.17: Isometric strengthening of back extensors and shoulder girdle muscles Fig.18: Trunk-muscle training while sitting on a “pezzy-ball” Fig.19: Muscle strengthening isometric exercise for the shoulder girdle in water (32°C) Figs.20a+b: A newly developed spinal orthosis, which is worn like a backpad, has been shown to improve posture, trunkmuscle strength and several parameters of quality of life in postmenopausal women with vertebral fractures due to osteoporosis [23]. Several exercises are not suitable for people with osteoporosis as they can exert strong force on relatively weak bone. Dynamic abdominal exercises like sit-ups and excessive trunk flexion can cause vertebral crush fractures. Twisting movements such as a golf swing can also cause fractures [24]. Exercises that involve abrupt or explosive loading, or high-impact loading, are also contraindicated. Daily activities such as bending to pick up objects can cause vertebral fracture and should be avoided [25]. Figures: Fig.1: Courtesy of Mehrsheed Sinaki, M.D., Mayo-Clinic and MayoMedical School Rochester, MN, U.S.A. Figs.2-12: Courtesy of Wolfgang Kemmler, M.D. and Klaus Engelke, Ph.D., University of Erlangen, Erlangen, Germany. Figs.13,15,19: Courtesy of Christian Hinz, M.D., Clinic „DER FÜRSTENHOF“, Bad Pyrmont, Germany Fig.14: Courtesy of Ling Qin, Ph.D., Dept. of Orthopaedics, Chinese University of Hong Kong, China Figs.16-18, 20: Courtesy of Michael Pfeifer, M.D. and Helmut W. Minne, M.D., Clinic “DER FÜRSTENHOF” and Institute of Clinical Osteology, Bad Pyrmont, Germany Project Advisors: Gulseren Akyuz, Turkey Steven Boonen, Belgium Moira O'Brien, Ireland Outi Pohjolainen, Finland Mehrsheed Sinaki, USA Ethel Siris, USA Rene Rizzoli, Switzerland José Zanchetta, Argentina References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Sallis JF, Owen N. Physical activity and behavioural medicine. Thousand Oaks. Ca: Sage, 1998:210. Kannus P, Sievanen H, Vuori I. Physical loading and bone. Bone 1996;18:1-3. Reid C, Dyck L, McKay H et al. The benefits of physical activity for women and girls: a multidisciplinary perspective. Vancouver: British Columbia Centers of Excellence in Women`s Health 1999:249. Khan K, McKay H, Kannus P, Bailey D, Wark J, Bennell K. Physical activity and bone health. Human Kinetics. IL, 2001:103. Pfeifer M, Sinaki M, Geusens P, Boonen S, Preisinger E, Minne HW. Musculoskeletal rehabilitation in osteoporosis: a review. J Bone Miner Res 2004;19:1208-1214. Bailey DA, Faulkner RA, McKay HA. Growth, physical activity and bone mineral acquisition. In: Holloszy JO et al. Ed. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1996;24:233-266. Morris FL, Naughton GA, Gibbs JL et al. Prospective 10-month exercise intervention in premenarcheal girls: positive effects on bone and lean mass. J Bone Miner Res 1997;12:1453-1462. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. Bradney M, Pearce C, Naughton G et al. Moderate exercise during growth in prepubertal boys: changes in bone mass, size, volumetric density and bone strength. A controlled study. J Bone Miner Res 1998;13:1814-1821. Gortmaker SL, Must A, Sobol AM et al. Television viewing as a cause of increasing obesity among children in the United States 1986-1990. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1996;150:356-362. Heinonen A, Kannus P, Sievänen H et al. Randomised controlled trial of effect of high-impact exercise on selected risk factors for osteoporosis. Lancet 1996;348:1343-1347. Friedlander AL, Genant HK, Sadowsky S et al. A two-year program of aerobics and weight training enhances bone mineral density of young women. J Bone Miner Res 1995;10:574-585. Sinaki M, Itoi E, Wahner HW, Wollan P, Gelzcer R, Mullan BP Collins DA, Hodgson SF. Stronger back muscles reduce the incidence of vertebral fractures: A prospective 10 year follow-up of postmenopausal women. Bone 2002;30:836-841. Kemmler W, Lauber D, Weineck J, Hensen J, Kalender W, Engelke K. Benefits of 2 years of intense exercise on bone density, physical fitness, and blood lipids in early postmenopausal osteopenic women. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1084-1091. Kujala UM, Kaprio J, Kannus P et al. Physical activity and osteoporotic hip fracture risk in men. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:705-708. Fujimura R, Ashizawa N, Watanabe M et al. Effect of resistance exercise training on bone formation and resorption in young male subjects assessed by biomarkers of bone metabolism. J Bone Miner Res 1997;12:656-662. Lord SR, Sherrington C, Menz HB. Falls in older people: risk factors and strategies for prevention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001:1-260. Tinetti ME, Baker DI, McAvay G et al. A multifactorial intervention to reduce the risk of falling among elderly people living in the community. N Engl J Med 1994;331:821-827. Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM et al. Randomised controlled trial of a general practice programme of home based exercise to prevent falls in elderly women. Br Med J 1997;315:1065-1069. Campbell AJ, Robertson M, Gardner M et al. Falls prevention over 2 years : a randomised controlled trial in women 80 years and older. Age Ageing 1999;28:513-518. Wolf SL, Barnhart MX, Kutner NG et al. Reducing frailty and falls in older persons: an investigation of Tai Chi and computerized training. J Am Geriatr Soc 1996;44:489-497. Chan K, Qin L, Lau M et al. A randomized prospective study of the effects of Tai Chi Chun exercise on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85:717722. Carter ND, Khan KM, McKay HA et al. Community-based exercise program reduces risk factors for falls in 65 – 75 year old women with osteoporosis: randomised controlled trial. CMAJ 2002;167:997-1004. Pfeifer M, Begerow B, Minne HW. Randomized trial of effects of a newly developed spinal orthosis on posture, trunk muscle strength and quality of life in postmenopausal women with spinal osteoporosis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2004;83:177-86. Ekin JA, Sinaki M. Vertebral compression fractures sustained during golfing: report of three cases. Mayo Clin Proc 1993;68:566-570. Sinaki M, Mikkelsen BA. Postmenopausal spinal osteoporosis: flexion versus extension exercises. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1984;65:593-596. Page Top Homepage | Search | Sitemap | Contact IOF | Members Only © 2005 International Osteoporosis Foundation: About IOF | Legal Disclaimer