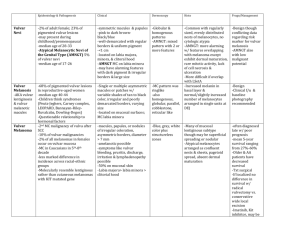

Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Vulvar Cancer

advertisement

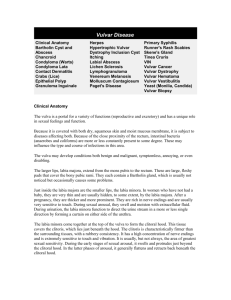

Agreed 2009 Review 2012 MEDICAL PROTOCOL ONCOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT OF VULVAR CANCER These guidelines have been developed by members of the Gynaecological Oncology Guidelines Group, for approval by the Merseyside and Cheshire Gynaecological Cancer Network Group. 1. Background...................................................................................................................... 3 2. Diagnosis and Referral ..................................................................................................... 4 3. Staging ............................................................................................................................ 5 4. Prognostic factors ............................................................................................................ 5 5. Pre-treatment assessment ................................................................................................ 6 6. Treatment ........................................................................................................................ 6 7. Surgery ............................................................................................................................. 7 Surgery in early disease: ................................................................................................... 7 Vulvo-vaginal Melanoma .................................................................................................... 8 Surgery in advanced disease: ............................................................................................ 9 8. Radiotherapy.................................................................................................................. 10 I. Primary Radiotherapy ................................................................................................... 10 II. Adjuvant Radiotherapy................................................................................................. 10 III. Palliative Radiotherapy ............................................................................................... 11 IV. Irradiation of Inguinal Nodes....................................................................................... 11 9. Chemoradiation.............................................................................................................. 11 10. Chemotherapy ............................................................................................................. 12 11. Treatment at Relapse .................................................................................................. 12 12. Hormone therapy .......................................................................................................... 12 13. Palliative Care and Nursing care ................................................................................... 13 14. Follow-up ..................................................................................................................... 14 15. Maintenance of Quality ................................................................................................ 14 1|P age Agreed 2009 Review 2012 FIGO Staging Description ................................................................................................... 15 Appendix 1 .......................................................................................................................... 16 Radical Radiotherapy....................................................................................................... 16 Concurrent Chemoradiation ............................................................................................. 16 Palliative Radiotherapy dose schedules ........................................................................... 16 References ......................................................................................................................... 17 2|P age Agreed 2009 Review 2012 1. Background Vulvar cancer is an uncommon illness with fewer than 800 cases registered in the UK each year. Hence most information about it comes from small personal series. In establishing these guidelines we have drawn upon previously published guideline texts, relevant published papers and chapters, and the recent RCOG publication, “Clinical Recommendations for the Management of Vulvar Cancer”1 Ninety percent of all vulvar cancers are squamous in origin, histological type being of importance because it is a variable affecting the likelihood of lymph node involvement. Survival is closely related to lymph node involvement. For those without any lymph node involvement 5-yr-survival is 80% but this falls to 50% if groin nodes are involved and to 10-15% if iliac or other pelvic nodes are involved. Overall 30% of patients presenting with vulvar cancer will be found to have nodal metastasis. Multifactorial analysis shows that nodal status and the diameters of the primary tumour are the only two variables which are associated with prognosis 2. These two variables, of course, simply represent advancing stage of disease. There is no screening test available for vulvar cancer although a number of precursor lesions are recognised. These include Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), and Paget’s disease of the vulva, and it is therefore appropriate to offer women with these conditions long-term surveillance. Patients with lichen sclerosus responsive to topical treatment may be discharged, but advised that they should seek re-referral in the event of any symptomatic deterioration. It should also be remembered that women who develop a vulvar cancer are at an increased risk of developing other genital cancers, particularly cervix. Surgery has been the treatment of choice for most women with vulvar cancer. Until recently this has involved a radical vulvectomy combined with a bilateral groin node dissection as popularised by Stanley Way in the 1950s. He clearly demonstrated the superiority of such radical surgery over simple vulvectomy and hence this approach came into use for virtually all vulvar cancers. An improved understanding of the disease, its natural history and prognostic factors has recently led to a change in 3|P age Agreed 2009 Review 2012 practice. Contemporary thinking emphasises individualisation of care and recognises that it is possible to adhere to the important principles of wide excision of the primary tumour and appropriate node dissection without performing a radical vulvectomy and bilateral node dissection on all patients. Another change in practice has been the introduction of combined modality therapy. This includes the use of radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy. Significant response can be achieved with well-planned radiotherapy, with or without chemotherapy. This may be of particular importance in advanced disease or where a tumour affects midline structures which are not amenable to surgical resection. These guidelines will relate to all histological types of cancer occurring on the vulva. 2. Diagnosis and Referral Early diagnosis is vital if survival is to be improved and the morbidity of treatment reduced. Factors which may assist primary care doctors in making or suspecting a diagnosis include the following: a) Vulvar cancer is a disease which is most frequent in elderly women b) Vulvar pain, burning, pruritus and soreness can all be associated with vulvar cancer. However a lack of symptoms does not exclude invasive disease since some tumours are asymptomatic. c) ANY vulvar symptom should prompt an examination of the lower genital tract. d) Warts are uncommon in elderly women and should be regarded with suspicion. In pre-menopausal women “warts” may initially be treated as condolymata accuminata but persistent warts should be referred for an excision biopsy. It is recommended that referral should be made if any of the following changes are detected: a swelling, polyp, lump or ulcer colour change- whitening or pigment deposition elevation and/or irregularity or surface contour a clinical “wart” 4|P age Agreed 2009 Review 2012 irregular fungating mass an ulcer with raised rolled edges enlarged groin nodes If invasive disease is suspected then the patient should be referred to a clinician with an interest in vulvar disease, with a view to onward referral to the network Gynaecological Oncology Centre if invasive cancer of any stage is confirmed. It is important that relevant histological material should be sent to the specialist gynaecological pathologist in the GOC. Referrals should be made within the current rapid access time limits stipulated by the Department of Health. Diagnosis should in most cases be confirmed by a biopsy prior to definitive surgery. Occasionally, where the clinical situation dictates, definitive surgery to the lesion may be performed. In general, surgery to the groin nodes should not be performed prior to pathological confirmation of invasive disease. If lesions are small (<2cm in diameter) then it is sometime appropriate to excise the whole of the lesion as a diagnostic biopsy. It is important to keep detailed notes regarding the site and size of the lesion in case further treatment is required. It may be helpful to take a clinical photograph prior to surgery in these circumstances, with the patient's express consent. 3. Staging This is perhaps the worst and most illogical staging system used in gynaecological oncology. It is a clinical staging system except for the recent addition of stage 1a which is a histological classification. It is hard to understand why a histological approach could not have been introduced for lymph node involvement since this is the most important prognostic factor. See Appendix 1. 4. Prognostic factors The two factors which are significantly associated with prognosis are nodal involvement and the size of the primary lesion2. 5|P age Agreed 2009 Review 2012 5. Pre-treatment assessment The most important investigation is a biopsy to confirm the diagnosis and assess depth of invasion. Biopsies are normally representative although smaller lesions may be completely excised. A representative biopsy should include an area of epithelium where there is a transition from normal to abnormal tissue. Biopsies should be sent for examination by a pathologist with a special interest in gynaecological oncology. Other investigations may include: FBC Biochemical profile Chest X-ray appropriate imaging to assess extent of disease and nodal status - this may include modalities such as Ultrasonography, CT or MRI scanning. Imaging of pelvic nodes is indicated if the groin is clinically suspicious. Biopsy or FNA of clinically suspicious nodes or other metastases where the result may alter management 6. Treatment Although considerable change has taken place in the management of vulvar cancer during the last decade, the principles of management remain unchanged. All patients need assessment for: 1) appropriate treatment for the primary site of disease 2) appropriate treatment for potential lymph node metastases. Since the presentation of vulvar cancer may vary enormously, each case needs to be judged on its own merits. As alluded to above, treatment may involve surgery, radiotherapy or chemotherapy and in some cases a combination of all three. There is also an increasing use of plastic surgery techniques. This may lessen the surgical morbidity by allowing closure of tissues without undue tension and could reduce long-term psycho-sexual morbidity associated with the scarring that follows the standard radical approach. Many factors will influence decisions regarding management including the site and size of the primary tumour and its histological 6|P age Agreed 2009 Review 2012 features, the presence or absence of nodal metastasis, the fitness of the patient and her informed decision. In these guidelines, the management of the primary tumour and the nodes will discussed in turn. Furthermore, in order to refine the broad principles of treatment into a management programme, two categories of disease, “early” and “advanced” will be considered separately. These can be defined as: Early Disease: Disease that is limited on clinical examination to the vulva with no evidence of nodal metastasis. Advanced Disease: Disease in which nodal metastasis is suspected and/or where excision of the primary tumour would involve sacrifice of important midline structures. 7. Surgery Surgery in early disease: Management of the primary tumour should involve a radical wide local excision. The main aim of the surgery is to remove the primary tumour with minimum 1cm clinical margins of disease-free tissue in all directions. This approach reflects evidence demonstrating that the risk of local recurrence is related directly to the size of the surgical excision margins3,4. Consideration should also be given to the removal of adjacent areas of abnormal epithelium (e.g. VIN or Lichen sclerosus) since it is possible that they could contain small, separate foci of invasion. Surgery to assess the possibility of nodal metastasis is necessary in all cases except 1) Stage 1a disease5. 2) Basal cell carcinoma and verrucous carcinoma - rarely associated with metastasis6,7. 3) Malignant melanoma - no evidence of any nodal involvement8. In most cases bilateral groin node dissection will be required because of the extensive crossover of lymphatic channels in the vulva. However in very lateral 7|P age Agreed 2009 Review 2012 tumours whose medial edge lies at least 2 cm from the midline ipsilateral groin node dissection may be performed initially, with recourse to dissection or irradiation of the contralateral nodes if the ipsilateral histology is positive. Surgery can be carried out by the “triple incision” technique described by Hacker9 since the incidence of skin bridge recurrence in early-stage disease is very low. It is recommended that superficial groin nodes as well as deep femoral nodes are removed as the removal of superficial nodes alone is associated with a higher risk of groin node recurrence 10. Recent research indicates that it is possible to accurately predict nodal metastasis using sentinel node biopsy in patients with early vulvar cancer (<4cm) 11. A. Van der Zee et al performed sentinel node procedure on 623 groins, they found that recurrence rate was low (n=6) and survival excellent and treatment related morbidity minimal. A large RCT is due to commence within the next 12 months. Until then sentinel node biopsy should only be performed as part of a trial and after appropriate training of the team involved. Another method of follow up for patients who have declined groin dissection or been deemed unfit for surgery is a combination of ultrasonography and fine needle aspiration and cytology12. At LWH over the last 4 years have assessed 40 patients with a positive predictive rate of 100%, and we have had one patient who developed a groin recurrence 6 months after initial treatment. Vulvo-vaginal Melanoma The risk of recurrence and therefore survival in vulval melanomas is mostly related to size of the tumour and the depth of invasion. The management of the groin nodes in melanoma is controversial and has little effect on survival but may provide local control of the groins. Thus, if nodes are palpable then they should be removed. There is however no indication for groin dissection when the depth of invasion is less than .76mm as the risk of metastasis is almost zero. For patients with a depth of invasion between 1mm and 4 mm but without palpable nodes, ultrasonography and fine needle aspiration can be offered. The role of sentinel node in this group has yet to be decided. Interestingly the role of cutaneous melanoma in this specific group has shown a survival advantage with sentinel node biopsy (MSLT-1). 8|P age Agreed 2009 Review 2012 New cases of vulvovaginal melanoma should be referred to the gynaecological MDT, who will in turn notify the network melanoma MDT with a view to arranging combined management as indicated by each individual presentation. Surgery in advanced disease: The principles of surgery are unchanged in that wide excision of the disease with at least 1cm clinical margins is the aim. The surgery required will of course depend upon the size and site of disease and the involvement of any important midline structures. Primary radiotherapy or chemoradiation is advised when surgery might be significantly morbid, and in some patients may remove the need for surgery altogether if a complete response is achieved. Two studies have suggested that preoperative chemoradiation can reduce the need for defunctioning stomas 13,14. Clearly the surgery required for advanced disease will be more radical than for early disease and more likely to involve radical vulvectomy or even exenterative surgery with the formation of faecal stomas or urinary conduit where necessary. The size of the deficit left behind after removing the primary tumour may also be more difficult to close by primary closure. It is therefore appropriate to consider using reconstructive surgical techniques in some cases. These procedures may be performed by the gynaecological oncologist or in conjunction with plastic surgery colleagues depending upon the procedure required. Groin node dissection is appropriate in all cases of late disease unless there are fixed and/or ulcerated groin nodes present. In these circumstances the involvement of the nodes should be confirmed by biopsy (open, trucut or FNA). The appropriate treatment options include palliative radiotherapy or radical treatment using radiotherapy +/- chemotherapy with surgery later if there is good response to treatment. 9|P age Agreed 2009 Review 2012 8. Radiotherapy For early stage, surgery is the treatment of choice. Radiotherapy given alone or in conjunction with chemotherapy may be used in advanced stage to downstage the tumour prior to surgery or as a primary treatment if there is complete response. The use of radiotherapy prior to surgery will of course be determined by clinical factors relating to the extent and site of the disease. I. Primary Radiotherapy 1) Very small lesions in unfit patients - Radiotherapy can be limited to the vulva treating inguinal nodes at recurrence. 2) Patients with clitoral lesions where surgery would be associated with major psychosexual sequelae. 3) Patients with advanced disease where primary surgery is inappropriate - radical radiotherapy alone or in combination with concurrent chemotherapy may be considered. II. Adjuvant Radiotherapy Factors which will influence the need for radiotherapy in an adjuvant setting are related to the pathological findings from operative specimens. These include the surgical margins since the risk of local recurrence increases as the disease-free margin decreases (>8mm = 0%; 8-4.8mm = 8%; <4.8mm = 54%)3,4 . Adjuvant radiotherapy for patients with close or involved margins does improve local control. In patients with positive nodes after radical surgery, adjuvant Radiotherapy significantly improves survival. A randomised GOG study15 showed 28% improvement in survival due to decreased incidence of groin recurrence. Other factors which may influence the decision to give adjuvant radiotherapy include the presence of an infiltrative growth pattern and lymphovascular space involvement both of which are associated with an increased risk of local recurrence though not of nodal metastasis. The majority of recurrences after surgery are locoregional16 and a 10 | P a g e Agreed 2009 Review 2012 number of clinicopathological variables have been identified which predict local recurrences and overall3,17. Adjuvant radiotherapy should be considered: 1) When two or more nodes are involved or if a single node is completely replaced by tumour or has extra-capsular spread. 2) If the excision margin is less than 8mm, but surgical re-excision is an equally valid approach. Surveillance with surgical salvage at recurrence is also valid in selected cases. 3) If one groin is node positive and the other has not been dissected, both groins and the pelvis should be considered for treatment. III. Palliative Radiotherapy In unfit patients with poor performance status and advanced tumours, a palliative approach is recommended to control symptoms such as pain and bleeding. IV. Irradiation of Inguinal Nodes Surgical dissection remains the treatment of choice, although it is not easy to draw conclusions about the efficacy of inguinal irradiation as primary treatment. A GOG study comparing groin dissection to groin radiotherapy was closed prematurely as an excess of groin failure was noted in the irradiated arm 15. There are number of criticisms of this study. It is clear that the groin nodes would have been inadequately treated in many patients in this study. We have to accept from this data that radiotherapy may be inferior to groin dissection and its use alone should be reserved for the less fit patients. 9. Chemoradiation Chemoradiation has never been compared with radiation alone in the pre-operative setting in vulvar cancer. Several small single arm studies and a recent larger GOG phase II study have shown high response rates averting the need for exenteration in most patients 18. In the GOG study almost half the patients had no visible cancer at the time of surgery and the vast majority of these had complete pathological 11 | P a g e Agreed 2009 Review 2012 responses. This has lead to questioning the role of surgery in patients having complete response. Unlike for anal carcinoma, there is currently insufficient evidence to advocate chemoradiation as the sole treatment of vulvar cancer. The morbidity of chemoradiation is the major issue and patients have to be carefully selected for this aggressive approach. Ideal patients are those with large tumours where surgery would need to be exenterative. 10. Chemotherapy Cytotoxic chemotherapy is not regarded as standard treatment in the management of vulvar cancers but can be used in selected patients with metastatic disease. The drugs of choice are 5-Fluorouracil and cisplatin, alone or in combination. Single agent Taxol is considered in patients who progress after first line chemotherapy. The response rate to chemotherapy is low and the duration of response of the order of 36months. Suitable patients are those with no co-existing morbidities, and normal organ function. In view of the age group of the patients with vulvar cancer it is rarely considered. 11. Treatment at Relapse Some patients particularly those with local vulvar relapse can be salvaged with further surgery. Generally patients with nodal and/or distant failure have poor prognosis and palliative treatments are appropriate. Selected patients may be considered on an individual basis for more aggressive treatment. 12. Hormone therapy Hormonal therapy has no significant place in the management of vulvar cancer. There are no contraindications to the prescription of hormone replacement therapy in women who have suffered from this disease. 12 | P a g e Agreed 2009 Review 2012 13. Palliative Care and Nursing care Palliative care input is appropriate to consider at all stages of the patient’s cancer journey. Please refer to the separate palliative care guideline for detailed advice. All women with a diagnosis of a Gynaecological Cancer should be offered the support of, and have access to a Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS), in order to facilitate the woman’s needs throughout the Cancer Journey, including those of her partner or carer. The skills of the C.N.S. as a consultant, practitioner and educator can be drawn upon at all stages throughout their illness, from the pre-diagnosis to the terminal stage – incorporating the Specialist Palliative Care Services provided in the hospital and the community setting. Bereavement Support will also be available, if appropriate. Important aspects of the role are to provide advice, support, information and to effectively incorporate appropriate resources. The C.N.S. will be receptive to the social, physical, psychological, cultural, sexual and spiritual needs of the patient. The aim of the patient support is to assist with the improvement in the quality of their lives, allowing them to become more empowered; to help take control and enhance their self esteem. The C.N.S. works closely with Surgeons, Oncologists, Radiotherapists, Consultants in Palliative Medicine and others (Nurses & P.A.M.s). They will undertake a number of key responsibilities including: Linking with other professionals who can help the patients throughout the system A resource for information and support to the patient carer and other H.C.P.s Liaison point for other health care professionals in primary and secondary care Teacher and Educator Researcher Standards and Audit Co-ordinator Co-ordinate Care Services 13 | P a g e Agreed 2009 Review 2012 14. Follow-up Standard: Four monthly for years 1 and 2, six monthly to 3 years. Discharge with open access to CNS in the event of new symptoms or concerns. CNS holistic assessment is carried out 6 weeks after the completion of primary treatment. A careful examination of the vulva and examination of the pelvis and inguinal regions is required. Patients who have associated VIN or Lichen sclerosus may be reviewed at intervals in a colposcopy clinic where vulvoscopy can be performed. Longer term follow-up may be considered in patients treated with radiotherapy. 15. Maintenance of Quality These guidelines conform to: Improving Outcomes in Gynaecological Cancers. NHS Executive 1999. RCOG recommendations on specialists in gynaecological oncology, 1996. 14 | P a g e Agreed 2009 Review 2012 FIGO Staging Description FIGO Description TNM 1a Lesion confined to vulva with <1mm invasion, T1N0M0 superficially invasive vulvar carcinoma 1b All lesions confined to vulva with diameter <2cm and no T1N0M0 clinically suspicious groin nodes 2 All lesions confined to the vulva with a maximum T2N0M0 diameter >2cm and no suspicious groin nodes 3 Lesions extending beyond vulva but without grossly T3N0M0 positive T3N1M0 groin nodes T3N2M0 T1N2M0 Lesions of any size confined to the vulva and having T2N2M0 clinically suspicious groin nodes 4 Lesions with grossly positive groin nodes regardless T1N3M0 of T2N3M0 the extent of the primary T3N3M0 T4N3M0 Lesions involving mucosa of rectum, bladder, urethra T4N0M0T4N or bone 1M0 T4N2M0 All cases of distant metastases M1A M1B 15 | P a g e Agreed 2009 Review 2012 Appendix 1 RADIOTHERAPY DETAILS Radical Radiotherapy Radiotherapy dose of 60 Gy or equivalent. 45 Gy in 25 fractions over 5 weeks followed by phase II to gross disease, to equivalent dose of 60 Gy. Preoperative dose of 45 Gy in 25 fractions over 5 weeks with concurrent chemotherapy in selected cases. Concurrent Chemoradiation 45 Gy in 25 fractions over 5 weeks with concurrent 5-fluorouracil infusion plus cisplatin on weeks 1 and 4, or weekly cisplatin for 5 weeks. Followed by small volume boost taking the dose to 60 Gy. 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions with concurrent 5-FU in 2 phases followed by boost (as above) to a total dose equivalent to 60 Gy. A split course is recommended in patients with severe acute skin reactions. Palliative Radiotherapy dose schedules 30 Gy in 10 fractions over 2 weeks 20 Gy in 5 fractions over 1 week 8 Gy single fractions 16 | P a g e Agreed 2009 Review 2012 References 1 RCOG publications. (2006) Clinical Recommendations for the Management of Vulvar Cancer. July 1999. 2 Holmsley, HD, Bundy, BN, Sedlis, A et al (1991). Assessment of current International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging of vulvar carcinoma relative to prognostic factors for survival (a Gynaecologic oncology group study). Am J Obstet Gynecol 164, (4), 997-1004. 3 Heaps, JM, Yao SF, Montz FJ, Hacker NF, Bereck JS. (1990). Surgical- pathological variables predictive of local recurrence in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol 38, 309-314. 4 Hacker NF. And Van der Velden J. (1993) Conservative management of early vulvar cancer. Cancer71, 1673 - 1677. 5 Herod JJO 6 Partridge EE, Murad T, Shingleton HM. Et al. (1980) Verrucous lesions of the female genitalia 2. Verrucous carcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol 137, 412-418. 7 Helm CW, Shingleton HM. et al. (1992) The management of squamous carcinaom of the vulva. Curent Obstet Gynecol 2, 31-37. 8 Davison T, Kissin M and Westbury C. (1987) Vulvo-vaginal melanoma - should radical surgery be abandoned? Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 94, 473-476. 9 Hacker NF, Leuchter RS, Bereck, JS Castaldo TW and Lagasse LD. (1981). Radical vulvectomy and bilateral inguinal lymphadenectomy through separate groin incisions. Obstet Gynecol. 58, 574-579. 10 Stehman FB, Bundy BN, Dvoretsky PM and Creasman WT (1992). Early stage 1 carcinoma of the vulva treated with superficial inguinal lymphadenectomy and modified rasdical hemivulvectomy. A prospective study of the GOG. Obstet Gybecol. 79, 490-497. 11 Sentinel Node Dissection Is Safe in the Treatment of Early-Stage Vulvar Cancer. A. Van der Zee et al. Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol 26, No 6 (February 20), 2008: pp. 884-889. 17 | P a g e Agreed 2009 Review 2012 12 The role of high resolution ultrasound with guided cytology of groin lymph nodes in the management of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: a pilot study. Moskovic E. et al. BJOG 1999 Aug;106(8):863-7. 13 Hacker NF, Berek JS, Juillard JF and lagasse LD (1984). Pre-operative radiotherpy for locally advanced vulvar cancer. Cancer 54, 2056-2061. 14 Rotmensch J, Rubin SJ, Sutton HG, Javaheri G, Halpern HJ, Schwarz JL, Stewart M, Weichselbaum RR and Herbst AL. (1990) Pre-operative radiotherapy followed by radical vulvevctomy with inguinal lymphadencetomy for advancedf vulvar carcinomas. Gynecol Oncol 36, 181-184. 15 Homsley HD, Bundy LN, Sedlis A, Adcock L. (1986). Radiation therapy versus pelvic node resection for carcinoma of the vulva with positive groin nodes. Obstet Gynecol 68: 733-740. 16 Bryson SC, Dembo AJ, Colgan TJ et al (1991) Invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva defining low and high risk groups for recurrence. Int J Gynecol. Cancer, 1, 25-31 17 Hopkins MP, Reid GC, Vettrano I et al (1991) Squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva prognostic factors influencing survival. Gynecol. Oncol, 43, 113-17 18 Moore D, Thomas G, Montana G. (1998). Preoperative chemoradiation for advanced vulvar cancer: a phase II study of the Gynaecologic Oncology group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 42: 79-85 18 | P a g e