Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

advertisement

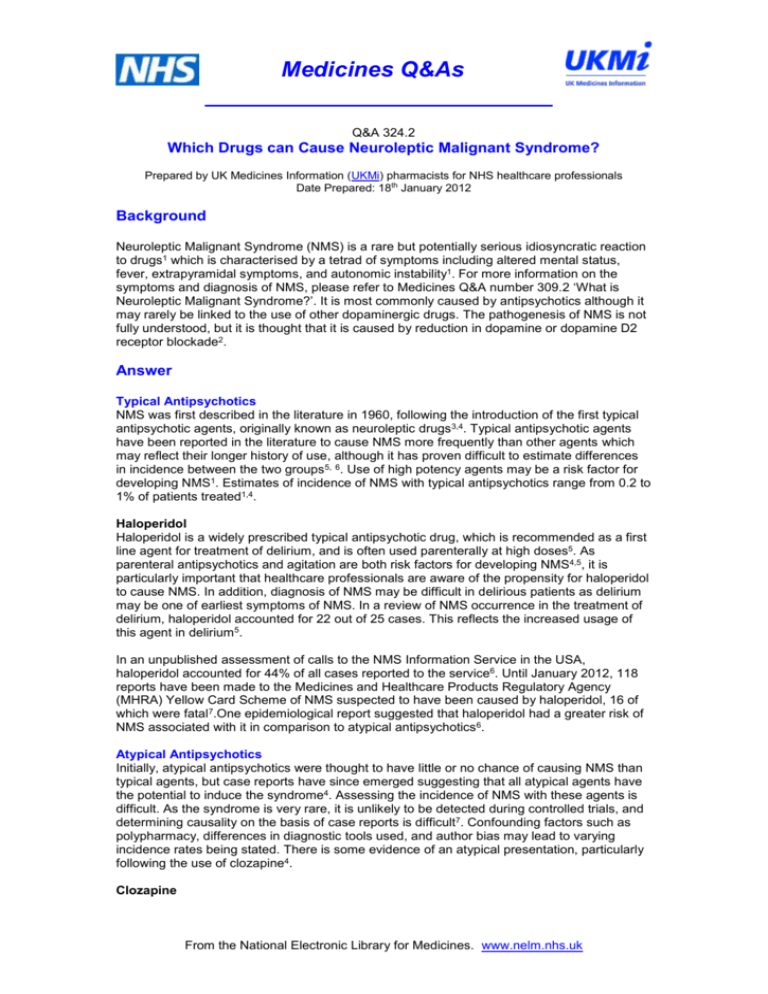

Medicines Q&As Q&A 324.2 Which Drugs can Cause Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome? Prepared by UK Medicines Information (UKMi) pharmacists for NHS healthcare professionals Date Prepared: 18th January 2012 Background Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) is a rare but potentially serious idiosyncratic reaction to drugs1 which is characterised by a tetrad of symptoms including altered mental status, fever, extrapyramidal symptoms, and autonomic instability1. For more information on the symptoms and diagnosis of NMS, please refer to Medicines Q&A number 309.2 ‘What is Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome?’. It is most commonly caused by antipsychotics although it may rarely be linked to the use of other dopaminergic drugs. The pathogenesis of NMS is not fully understood, but it is thought that it is caused by reduction in dopamine or dopamine D2 receptor blockade2. Answer Typical Antipsychotics NMS was first described in the literature in 1960, following the introduction of the first typical antipsychotic agents, originally known as neuroleptic drugs 3,4. Typical antipsychotic agents have been reported in the literature to cause NMS more frequently than other agents which may reflect their longer history of use, although it has proven difficult to estimate differences in incidence between the two groups 5, 6. Use of high potency agents may be a risk factor for developing NMS1. Estimates of incidence of NMS with typical antipsychotics range from 0.2 to 1% of patients treated1,4. Haloperidol Haloperidol is a widely prescribed typical antipsychotic drug, which is recommended as a first line agent for treatment of delirium, and is often used parenterally at high doses5. As parenteral antipsychotics and agitation are both risk factors for developing NMS4,5, it is particularly important that healthcare professionals are aware of the propensity for haloperidol to cause NMS. In addition, diagnosis of NMS may be difficult in delirious patients as delirium may be one of earliest symptoms of NMS. In a review of NMS occurrence in the treatment of delirium, haloperidol accounted for 22 out of 25 cases. This reflects the increased usage of this agent in delirium5. In an unpublished assessment of calls to the NMS Information Service in the USA, haloperidol accounted for 44% of all cases reported to the service6. Until January 2012, 118 reports have been made to the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) Yellow Card Scheme of NMS suspected to have been caused by haloperidol, 16 of which were fatal7.One epidemiological report suggested that haloperidol had a greater risk of NMS associated with it in comparison to atypical antipsychotics 6. Atypical Antipsychotics Initially, atypical antipsychotics were thought to have little or no chance of causing NMS than typical agents, but case reports have since emerged suggesting that all atypical agents have the potential to induce the syndrome4. Assessing the incidence of NMS with these agents is difficult. As the syndrome is very rare, it is unlikely to be detected during controlled trials, and determining causality on the basis of case reports is difficult7. Confounding factors such as polypharmacy, differences in diagnostic tools used, and author bias may lead to varying incidence rates being stated. There is some evidence of an atypical presentation, particularly following the use of clozapine4. Clozapine From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk Medicines Q&As Clozapine adverse reactions include temperature elevations, tachycardia, stiffness, increased CK levels, and delirium8, which have significant overlap with the symptoms of NMS. Some debate has occurred in the literature regarding whether clozapine induced NMS is an extension of these adverse effects or a distinct syndrome, which appears to present differently to NMS caused by other drugs 4. Clozapine induced NMS seems to have an atypical onset, characterized by less likelihood of tremor and rigidity4. A different time course may occur in NMS produced by clozapine, with delayed onset of extrapyrimidal effects, which would account for this atypical presentation4. The MHRA has received 254 reports via its yellow card scheme of NMS suspected to be associated with clozapine, 3 of which were fatal9. Olanzapine Olanzapine induced NMS was first reported in 1998 and since then over 20 case reports have linked olanzapine with NMS onset. Only a minority of these cases seem to suggest an atypical onset, with most cases describing typical NMS features 4. MHRA yellow card reports indicate that 119 cases of suspected NMS have been reported, including 5 fatal cases10. Risperidone The majority of case reports regarding NMS caused by risperidone indicate that its onset is typical, although one theory suggests that a less severe form, particularly with less severe hyperthermia may be produced by risperidone, although this has not been investigated4. One case report describes a woman who suffered both an atypical and a typical presentation of NMS on exposure to risperidone. The patient was found to have a CYP2D6 phenotype associated with reduced metabolism of risperidone11. The MHRA has received 121 suspected reports, 6 of which were fatal12. Amisulpride The limited numbers of cases of NMS reported with amisulpride appear to describe a slightly altered onset, in that more cases are reported in older patients, and cases seemed to appear more rapidly after initiation of the drug4,13. The MHRA has received 53 suspected reports, 2 of which were fatal14. Aripiprazole Given that aripiprazole has partial dopamine agonist action, as opposed to other antipsychotics which act as dopamine antagonists, an atypical presentation of NMS may have been expected4. Case reports do seem to indicate that there is less likelihood of altered mental status and hyperthermia in the early stages of aripiprazole-induced NMS compared with typical NMS4. Diaphoresis is the main symptom in 37.5% of cases associated with aripiprazole15. Suspected reports via the yellow card scheme include 38 cases of NMS, 2 of which were fatal16. Quetiapine The case studies reported in the literature suggest that cases of NMS caused by quetiapine are of a typical nature. However, many of the reports are confounded by other factors such as co-prescription of another serotonergic drugs or lack of full clinical information4. One case report describes the development of severe confusion, somnolence, elevated creatine kinase, and extreme agitation in a 4 year old child who was taking 400mg quetiapine per day. The authors report that the fact the child had XYY syndrome may be a contributory factor to the development of NMS, along with the high dose administered 17. Indeed, a dose of 400mg in a child would be considered to be a potentially toxic dose18. Yellow card reports suggest that 55 cases of NMS have occurred which are suspected to be linked to quetiapine administration, one of which was fatal19. Paliperidone To date, only a few case reports have emerged in which NMS has occurred in response to paliperidone treatment. An atypical presentation appears to be associated with use of this drug20. From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk Medicines Q&As Dopamine Agonists A number of case reports appear in the literature of an NMS-like syndrome (NMLS) following withdrawal of levodopa preparations. Withdrawal of dopamine agonists mimics the dopamine antagonist action of antipsychotics and reduces the amount of usable dopamine in the brain, which is thought to be part of the pathogenesis of NMS21. Three cases following withdrawal of levodopa-carbidopa during a drug holiday period have been reported. In all three cases, the patients suffered the classic tetrad of symptoms. One of the cases occurred prior to complete drug withdrawal. The authors suggest that NMLS following drug holiday may be under-reported due to lack of recognition of the syndrome, and delayed presentation of symptoms22. Another case study reports an elderly woman who developed NMLS following slow withdrawal of levodopa23. Other, similar cases continue to be reported in the literature24,25. One case involved an elderly male with Parkinson’s Disease whose levodopa therapy was reduced gradually following implantation of a Deep Brain Stimulator. Selegiline was also discontinued26. An interaction between levodopa and a high-protein enteral feed led to the development of NMLS in one case27. The MHRA have received 10 reports of levodopa products (including combination products) suspected of causing NMS28. Withdrawal of other dopamine agonists including bromocriptine and amantadine can also lead to NMLS2. One case report of NMLS following amantadine withdrawal has established causality. The patient experienced symptoms of NMS due to a reduced dose of amantadine which resolved on the dose being increased. The symptoms recurred following re-challenge, then resolved the dose was increased29. Bromocriptine and levodopa have been used successfully as treatments for NMS caused by dopamine antagonist drugs4. Antidepressants There have been 23 reports of NMS occurring following antidepressant administration, but in 9 cases they were co-prescribed with antipsychotic drugs and pre-medication with antipsychotics had occurred in 11. Only 8 cases were reported following antidepressants alone, but the diagnosis of some of these cases is dubious. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) appeared to be more likely to cause NMS than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. A review of the case reports concludes that NMS associated with antidepressants alone is a very rare occurrence, but that antidepressants may increase serum levels of antipsychotics, leading to an increased risk of NMS due to the antipsychotic itself 30. Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs) produce a similar reaction to NMS when used in combination with TCAs, which may consist of agitation, delirium, hyperthermia and even death. If patients are taking a combination of an MAOI and an antipsychotic, MAOI toxicity will need to be ruled out before NMS is diagnosed22. Other Other drugs with dopaminergic activity have been reported to cause NMS. Of note are the prokinetic agents metoclopramide and domperidone, which act by blocking dopamine receptors31,32. It may be the case that, as patients prescribed these drugs may not be neurology patients, physicians are less likely to consider NMS as a cause of symptoms and have less experience of diagnosing and recognizing the syndrome. Metoclopramide The anti-emetic metoclopramide was first described to cause NMS in 198533. The MHRA has received 15 reports of NMS suspected to have been caused by metoclopramide, 3 of which were fatal34. A case report describes a six month old child with Freeman-Sheldon Syndrome who suffered NMS following administration of metoclopramide syrup. This is the youngest patient who has been reported to experience NMS, confirming that children are also at risk of developing the syndrome35. From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk Medicines Q&As Domperidone One case report describes NMS following domperidone administration in a 47 year old female with a family history of malignant hyperthermia36. Substances of Abuse Cocaine, amphetamines and ecstasy may cause an NMS like presentation. Alcohol and Sedative withdrawal and hallucinogen intoxication may cause symptoms which are easily confused with NMS2. Lithium It is thought that combinations of lithium and antipsychotic drugs may increase the risk of NMS presentation. It has also been suggested that lithium toxicity may contribute to an increased risk of permanent brain damage following an NMS episode 37. Summary NMS is a rare but potentially fatal adverse reaction to drugs. It is most commonly seen with antipsychotic agents Atypical agents may have a lower incidence of NMS than typical agents, although this is yet to be proved and case reports of NMS associated with most antipsychotic agents continue to emerge in the medical literature. NMS associated with clozapine may present atypically It may also rarely be associated with withdrawal or reduction of dose of dopamine agonists such as levodopa, amantadine and bromocriptine Metoclopramide and domperidone have reportedly caused NMS in some patients. Combinations of antipsychotics, or antipsychotics with lithium or antidepressants, may increase the risk of NMS developing. Limitations MHRA Drug analysis prints should be interpreted with caution due to the voluntary nature of the scheme. Causality of adverse effects does not need to be established for a report to be made. The number of reports is included in this Q&A only to reinforce that spontaneous reporting of neuroleptic malignant syndrome has occurred, not as an assessment of likelihood of risk. A detailed review of case reports in the literature is beyond the scope of this document. All information is correct at the time of writing. Disclaimer Medicines Q&As are intended for healthcare professionals and reflect UK practice. Each Q&A relates only to the clinical scenario described. Q&As are believed to accurately reflect the medical literature at the time of writing. The authors of Medicines Q&As are not responsible for the content of external websites and links are made available solely to indicate their potential usefulness to users of NeLM.You must use your judgement to determine the accuracy and relevance of the information they contain. See NeLM for full disclaimer. Quality Assurance Prepared by Hayley Johnson, Regional Drugs and Therapeutics Centre, Newcastle upon Tyne. Date Prepared 15th April 2010 Reviewed 18th January 2012 From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk Medicines Q&As Checked by Sarah Smith, Regional Drugs and Therapeutics Centre, Newcastle upon Tyne. Date of check 26th May 2010 18th April 2012 Search strategy MHRA Drug Analysis Prints EMBASE: **NEUROLEPTIC MALIGNANT SYNDROME/ *ANTIDEPRESSANT AGENT/ *HALOPERIDOL *ATYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS *LEVODOPA *AMANTADINE *BROMOCRIPTINE/ *METOCLOPRAMIDE/ MEDLINE: *NEUROLEPTIC MALIGNANT SYNDROME/ *BROMOCRIPTINE/ *METOCLOPRAMIDE/ *HALOPERIDOL *ATYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS *LEVODOPA *AMANTADINE *ANTIDEPRESSANT AGENT/ PSYCHINFO:*NEUROLEPTIC MALIGNANT SYNDROME/ CHLORPROMAZINE/ HALOPERIDOL/ *BROMOCRIPTINE/ *METOCLOPRAMIDE/ *HALOPERIDOL *ATYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS *LEVODOPA *AMANTADINE *ANTIDEPRESSANT AGENT/ NMSIS.org In-house resources References 1Taylor D, Paton C, and Kerwin R. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines. 11th Edition. London. Informa Healthcare 2012; 110-113 2 Maule E. Management of Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome. Br J Clin Pharm 2009; 1(7): 203-205. 3 Ramachandraiah CT, Subramaniam N, and Tancer M. The Story of Antipsychotics: Past and Present. Indian J Psychiatry 2009; 51(4): 324–326. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.58304. 4 Troller JN, Chen X, Sachdev PS. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Associated With Atypical Antipsychotic Drugs. CNS Drugs 2009; 23(6): 477-492. 5 Seitz DP and Gill SS. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Complicating Antipsychotic Treatment of Delirium or Agitation in Medical and Surgical Patients: Case Reports and a Review of the Literature. Psychosomatics 2009; 50(1): 8-15. 6 Strawn JR, Keck PE, Caroff SN. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome: Answers to 6 Tough questions. (unpublished) Accessed via www.nmsis.org on 27th March 2012. From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk Medicines Q&As 7 Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Drug Analysis Print: Haloperidol: Accessed via http://www.mhra.gov.uk/index.htm on 27th March 2012 8 Summary of Product Characteristics- Clozaril (clozapine). Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd. Accessed via http://www.medicines.org.uk/EMC/medicine/1277/SPC/Clozaril+25mg+and+100mg+Tablets/ on 27/03/2012 [date of revision of the text 09/06/2010] 9 Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Drug Analysis Print: Clozapine: Accessed via http://www.mhra.gov.uk/index.htm on 27th March 2012 10 Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Drug Analysis Print: Olanzapine: Accessed via http://www.mhra.gov.uk/index.htm on 27th March 2012 11 Ochi S, Kawasoe K, Masao A et al. A case study: neuroleptic malignant syndrome with risperidone and CYP2D6 variation. General Hospital Psychiatry 2011; 33: 640.e1-640.e2 12 Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Drug Analysis Print: Risperidone: Accessed via http://www.mhra.gov.uk/index.htm on 27th March 2012 13 Tu M and Hsiao C. Amisulpride and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Chang Gung Med J. 2011; 34(5) 536-539 14 Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Drug Analysis Print: Amisulpride: Accessed via http://www.mhra.gov.uk/index.htm on 27th March 2012 15 Chen Y and Su K. Early detection and management of atypical neuroleptic malignant syndrome secondary to aripiprazole. Schizophrenia Research 2011; 132: 97-98 16 Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Drug Analysis Print: Aripiprazole: Accessed via http://www.mhra.gov.uk/index.htm on 27th March 2012 17 Randolph T. Possible Contribution of XYY syndrome to neuroleptic malignant syndrome in a child receiving quetiapine. Am J Health-Syst-Pharm 2010; 67: 459-461 18 Quetiapine Monograph:Toxbase Accessed via http://www.toxbase.org/Poisons-Index-AZ/Q-Products/Quetiapine------------/ on 27th March 2012 19 Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Drug Analysis Print: Quetiapine: Accessed via http://www.mhra.gov.uk/index.htm on 27th March 2012 20 Han C, Lee S, and Pae C. Paliperidone-associated atypical neuroleptic malignant syndrome: a case report. Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry 2011; 650-651 21 Adnet P, Lestavel P and Krivosic-Horber R. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome. Br J Anaesthesia 2000; 85(1): 129-35 22 Friedman JH, and Feinberg SS. A Neuroleptic Malignant like Syndrome due to Levodopa Therapy Withdrawal 1985; JAMA 254(19): 2792-2795 23 Douglas A and Morris J. It was not just a heatwave! Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome in a patient with Parkinson’s Disease. Age and Aging 2006; 35: 640-641 24 Sharms J, Saxena S, and Singh A. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome with atypical neuroleptics and dopamine modulating drugs: Seven case reports. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders 2012; 18(S52): 1353-8020 25 Tapan U, Arik G, Altintas N et al. Levodopa withdrawal in Parkinson’s disease: A rare Cause of fever necessitating intensive care [Turkish]. Journal of Medical and Surgical Intensive Care medicine 2010; n1/2 (52-54): 1309-1689; 1309-6222 26 Ward C. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome in a Patient with Parkinson’s Disease: A Case Study. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing 2005; 37(3): 160-162 27 Bonnici A, Ruiner C, St-Laurent L et al. An interaction between levodopa and enteral nutrition resulting in neuroleptic malignant-like syndrome and prolonged ICU stay. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 2010; 44(9): 1504-1507 28 Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Drug Analysis Print: Levodopa: Accessed via http://www.mhra.gov.uk/index.htm on 27th March 2012 29 Bower D, Chalasanti P and Ammons JC. Withdrawal-induced neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1994; Mar;151(3):451-2 30 Assion HJ, Heinemann F and Laux G. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome under treatment with antidepressants? A critical review. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 248: 231-239 From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk Medicines Q&As 31 Metoclopramide monograph. Sweetman SC (ed), Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. [online] London: Pharmaceutical Press <http://www.medicinescomplete.com/> (Accessed on 27/03/2012) 32 Domperidone monograph. Sweetman SC (ed), Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. [online] London: Pharmaceutical Press < http://www.medicinescomplete.com/> (Accessed on 27/03/2012) 33 Robinson MB, Kennett RP et al. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome associated with metoclopramide. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 1995; 40: 1304. 34 Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Drug Analysis Print: Metoclopramide: Accessed via http://www.mhra.gov.uk/index.htm on 27th March 2012 35 Stein M, Sorscher M and Caroff S. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Induced by Metoclopramide in an Infant with Freeman-Sheldon Syndrome. Anaesthesia and Analgesia 2006; 3: 786-787 36 Spirt MJ, Chan W, Thieberg M and Sachar DB. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome induced by domperidone. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 1992; 37(6): 946-948 37 Lader M. Lethal Complications of antipsychotic drug medication. Clinical risk 2006; 12(3): 113-117 From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk