Lateral Epicondylitis: Old Terms deserve old treatments

advertisement

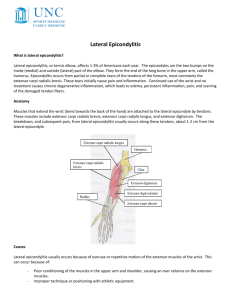

Lateral Epicondylitis: Old Terms Deserve Old Treatments By Gregg Doerr, DC, CCSP - ANJC Sports Council Tennis elbow, once described as lateral epicondylitis, is an old term and a misnomer about the condition. The term lateral epicondylitis refers to an inflammatory state of the common extensor tendon of the elbow. This is actually a rare occurrence. According to Boyer et al (1), “Signs of either acute or chronic inflammation have not been found in any surgical pathologic specimens in patients with clinically diagnosed lateral tennis elbow syndrome.” They state that only one study, which demonstrated tears in the extensor origin with symptoms of more than one year of lateral tennis elbow syndrome, showed “round cell infiltration.” What does occur histologically at these tendons is known as a tendinosis or tendonopathy. There are three basic elements of the tendinosis as described by Nirschl (2): 1. Fibroblastic hyperplasia, 2. Vascular Hyperplasia and 3. Abnormal Collagen Production. Fibroblastic hyperplasia is associated with an increase in fibroblastic proliferation, however, some of the fibroblast returns to their mesenchymal state, producing chodrocytes, oseteocytes, and vascular endothelial cells. While all of these cells produce an intrinsic healing potential, the nature of this injury is chaotic and without a true healing structure. Vascular hyperplasia is a production of vascular budding without resolution to the production of new vascular supply. This is similar to the granulation stage of healing, but without the eventual fibroblastic and maturation stages. Abnormal collagen production is a product of the increased fibroblastic proliferation, but without proper tensile loads and vascular communication, the collagen is laid down in cross linking and adhesions of decreased tensile strength and function (3, 4, 5). The above three phenomenon are known as an angiofibroblastic hyperplasia. Understanding the nature of this disorder gives us the necessary information to formulate a proper treatment plan for it. This condition is frequently treated with NSAIDS or cortisone injections. Since it is not an inflammatory state, it makes little sense to provide anti-inflammatory medication. In fact, the use of cortisone injections can actually lead to further degeneration of the tendinosis. In certain areas of the body, such as the Achilles tendon, use of injections has been related to rupture. It is possible that the direct needling of the tendon leads to a vascular communication leading to healing cascade, but the cortisone itself is the opposite of what needs to be done. Due to the degenerative nature of this injury and chronic hypoxia of the tissue, our focus should be three-pronged: 1. Mechanical load: Soft tissue techniques to initiate inflammatory cascade stimulating fibroblastic proliferation and collagen production. 2. Tenocyte stimulation: Strengthening program to produce cyclical loading of the tendon under a controlled environment stimulates tenocytes to produce collagen in a more organized fashion. 3. Lengthening of tissues through stretching of tendon and muscle leads to proper lengthening of tissue to prevent further contracture. In short, through of the use of proper soft tissue techniques and rehabilitation, we can initiate the healing cascade and properly remodel this degenerative tissue into viable tendon structure, increasing its tensile strength, and removing the chaotic tissue at the root of this condition. There are points of interest that should be considered in treating this condition. While most lateral epicondylopathies are the product of repetitive strain, there are some underlying conditions that should be properly evaluated in order to assure resolution of the condition. The simplest and most common of the complications is a chronic shortening of the flexor tendons. Almost every activity in our society requires a chronic overuse of our flexor group. Whether a chiropractor, computer/desk jockey, manual laborer, or tailor, we are dominated by flexor activity. With a chronic shortening, the extensor group must work considerably harder just to bring a finger back to a neutral position. The second of the complications is associated with the overhead athlete. Whether chronic or acute injury to the anterior band of the medial collateral ligament of the elbow, the lateral (extensor) group fires excessively in the stabilization of the elbow. Another less common injury is that of the joint complex itself. Anything from posterior lateral rotary instabilities to osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) can be associated or confused with lateral epicondylopathy. It is only through proper examination, a thorough history, and, when necessary, imagining studies, that we can properly diagnosis and treat the condition simply known as “tennis elbow.” 1. Kraushaar BS, Nirschl RF. Tendonosis of the elbow. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, 1999:259-278. 2. Kandemir U, Fu FH, McMahon PJ. Elbow injuries. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 2002; 14: 160-167 3. Field LD, Savoie FH. Common elbow injuries in sport. Sports Med 1998 Sep; 26 (3): 193-205 4. Fritz, RC. MR imaging of sports injury of the elbow. MR Imag Sports Inj 1999 Feb; 7 (1): 5172 5. Hammer WI. Functional Soft Tissue Examination and Treatment by Manual Methods. Aspen; 1999.