Pulmonary Bleeding in Infants and Children

advertisement

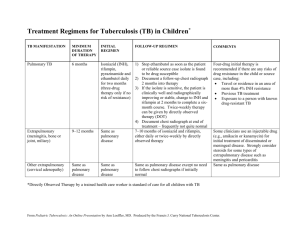

PULMONARY BLEEDING IN INFANTS AND CHILDREN Andrew A. Colin, MD Division of Pediatric Pulmonology, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL Andrew A. Colin, MD Division of Pediatric Pulmonology Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami 1580 NW 10th Avenue, Room 125 Miami, FL 33136 Telephone: (305) 243-3176 Fax: (305)243-1262 E-mail: acolin@med.miami.edu This discussion focuses on diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH). This paper is not intended to be a comprehensive review of the subject as previously undertaken by Godfrey1 and Nusslein2, but rather to highlight some recently presented novel aspects on this difficult topic, such as Acute Idiopathic Pulmonary Hemorrhage of Infancy (AIPH), a recent classification of DAH, and novel therapeutic methods using bronchoscopy. CLINICAL PRESENTATION: The typical presentation of DAH is the triad: hemoptysis, anemia and diffuse alveolar infiltrates, but the three elements rarely coexist. While in infants, who will be separately discussed below, overt hemorrhage from the airway is the common presentation; a fall in hematocrit (typically hypochromic, microcytic anemia) associated with respiratory disease is the hallmark of pulmonary bleeding. The onset of symptoms is variable: a fulminant onset with acute hemoptysis is occasionally fatal; however, most cases have an insidious presentation with anemia, pallor, weakness and poor weight gain. Some patients vomit swallowed blood and do not have hemoptysis. The physical examination is non-specific and ranges from dyspnea, with crackles and wheezing to the physical findings associated with pulmonary hypertension or frank respiratory failure. Fever and chest pain are sometimes associated with the bleeding episode, and may be the markers for a recurrent bleed. LABS: Pulmonary function testing in age appropriate children is non-specific, but diffusion studies (DLCO) may result unexpectedly high because of the rapid uptake of the tracer gas by hemoglobin in the alveolar spaces. Radiographic changes are non-specific as well, and range from minimal infiltrates to massive parenchymal involvement, The fleeting nature of the infiltrates may be a telltale sign. In patients with small frequent episodes of bleeding the radiographs may reflect chronic diffuse interstitial involvement and may change only minimally with an acute episode of bleeding. CT scan appears to offer no better specificity than the chest radiograph, though MRI of the lung may prove more useful in defining the presence of blood, showing decreased signal on the T2weighted images INCIDENCE: The incidence of pulmonary bleeding in childhood is low; hence there is little systematic information on bleeding in children. The incidence estimate in Sweden is 0.24 cases per million and a higher rate of 1.23 cases per million is reported from Japan. CAUSES OF HEMOSIDEROSIS: Because of the low incidence of DAH, little systematic information on causes of lung bleeding in childhood, and essentially none of large scale, is available. In one 10 year review from a large referral center, 228 children and young adults were reported: Cystic fibrosis (CF) represented 65%, Congenital heart disease 16%. The remaining 19% were infections (other than CF), neoplasms (2.6%), and other causes.3 Classification: As above, many of the cases occur in the context of cystic fibrosis or lung infections; predominantly tuberculosis. The remaining cases of “Idiopathic Pulmonary Hemosiderosis” were traditionally viewed as a wastebasket of many conditions, which were variable in nature and overall poorly understood. A recent review4 offers a systematic approach to classification of DAH emphasizing the distinction between disorders without pulmonary capillaritis; this group is broken down to those with noncardiovascular causes and cardiovascular cause. The other group includes the disorders with pulmonary capillaritis which typically carry a more ominous prognosis. Included in the latter group are Idiopathic pulmonary capillaritis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, Microscopic polyangiitis, Systemic lupus erythematosus, Goodpasture’s syndrome, Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, HenochSchonlein purpura, IgA nephropathy, Polyarteritis nodosa, Behcet syndrome, Cryoglobulinemia, Drug-induced capillaritis, and Idiopathic pulmonary–renal syndrome ACUTE IDIOPATHIC PULMONARY HEMORRHAGE OF INFANCY (AIPH) Infantile airway bleeding is an uncommon occurrence but has periodically emerged in clusters; historically in Greece, and more recently in Cleveland and Massachusetts. This entity was recognized by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) as unique and earned its definition in a publication in 2001: a clinically confirmed case is an illness in a previously healthy infant aged <1 year, with a gestational age >32 weeks, and no history of neonatal medical problems that could cause pulmonary hemorrhage. In addition, the cases are characterized by abrupt onset of overt bleeding or frank evidence of blood in the airway, a severe presentation leading to acute respiratory distress or failure, and diffuse pulmonary infiltrates on chest radiograph. In the mid 90s a series of 30 cases of AIPH was reported from Cleveland.5 Of these 77% were from the same geographic area and were African-American, with male predominance (77%), 73% required respiratory support, and 5 (16%) of them died. While the numbers were small it appears that corticosteroid administration had a protective role. Most infants were placed on corticosteroid therapy, 3/5 infants who died had not received steroids or stopped them soon after discharge, and 2/25 who survived did not receive steroids. An initial association of this cluster of AIPH was made to Stachybotrys chartarum, a mold that may be found in waterdamaged homes. Ultimately, this association has not been confirmed. AIPH in five infants in the Boston area were reported in 2004.6 No mortality was reported. The cause was assumed to be related to an underlying susceptibility to bleed, and von Willebrand Disease (VWD) was ultimately diagnosed in 3 of the infants. Such underlying vulnerability was thought to be precipitated by injury to the lungs, possibly a viral infection, but this was not substantiated. THE ROLE OF BRONCHOSCOPY IN AIRWAY AND PULMONARY BLEEDING Diagnostic: Flexible bronchoscopy is key in the initial diagnosis of DAH, in particular in cases who do not present with overt airway bleeding. In such cases bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) results in persistently blood-tinged return fluid.7 Repeat bronchoscopy has been proposed by the Cleveland group5 for therapeutic decision-making and long term follow-up. A scoring system for hemosiderin-laden macrophages was developed by them to allow comparison between repeated procedures through the long term follow-up. Therapeutic: Medical treatment of hemosiderosis is beyond the scope of this presentation. However, the use of bronchoscopy both flexible and rigid to control bleeding is common in the adult literature, but barely addressed in pediatrics. The previously cited review on diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in children4 does not list bronchoscopy related interventions to control bleeding. The largest report on a series of 14 patients with acute life-threatening pulmonary hemorrhage lists use of CO2 laser bronchoscopy, Nd-YAG laser bronchoscopy, endoscopic balloon occlusion of a lobe or main bronchus, topical airway vasoconstrictors and endoscopic tumor excision.8 An exciting innovation in the bronchoscopic interventions to control airway bleeding has recently emerged with the successful intrapulmonary instillation of activated recombinant factor VII (rFVIIa) to control DAH in a series of adult patients.9 Similarly, tranexamic acid, a synthetic anti-fibrinolytic agent has been reported in a series of 6 patients.10 The use of both agents is an extension of previous experience with their systemic administration to treat patients with recalcitrant pulmonary bleeding. Colin et al11 have recently reported Heslet et al’s9 protocol to instill rFVIIa to control an unremitting diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage of 4 weeks duration, as an intervention of last resort for a 16 year old patient with acute myelogenous leukemia. The hemorrhage was visualized during the procedure and its resolution following the treatment was immediate, unequivocal, and definitive. The remarkable ease and efficacy of this intervention makes it attractive for treatment of pulmonary hemorrhage in both adults and children. PROGNOSIS: There is little information about long term outcome of pulmonary hemosiderosis. Most informative are studies by Saeed12 and Le Clainche13 that suggest that the overall prognosis may not be favorable in the “idiopathic” cases. Thus, these cases require careful follow-up and appropriate treatment that most often consists of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapies. The Saeed paper12 emphasizes the beneficial long-term impact of immunosuppression therapy on the prognosis of DAH. Some cases with DAH may declare themselves in later life as having well-defined connective tissue or granulomatous diseases. While the infant population with AIPH discussed above likely reflects a different subclass within the “Idiopathic” group, individuals with recurrent bleeding and mortality have been reported. REFRENCES: 1. Godfrey S. Pulmonary hemorrhage/hemoptysis in children. Pediatr Pulmonol 2004;37(6):476-84. 2. Nuesslein TG, Teig N, Rieger CH. Pulmonary haemosiderosis in infants and children. Paediatr Respir Rev 2006;7(1):45-8. 3. Coss-Bu JA, Sachdeva RC, Bricker JT, Harrison GM, Jefferson LS. Hemoptysis: a 10- year retrospective study. Pediatrics 1997;100(3):E7. 4. Susarla SC, Fan LL. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage syndromes in children. Curr Opin Pediatr 2007;19(3):314-20. 5. Dearborn DG, Smith PG, Dahms BB, et al. Clinical profile of 30 infants with acute pulmonary hemorrhage in Cleveland. Pediatrics 2002;110(3):627-37. 6. Investigation of acute idiopathic pulmonary hemorrhage among infants - Massachusetts, December 2002-June 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004;53(35):817-20. 7. Collard HR, Schwarz MI. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Clin Chest Med 2004;25(3):583- 92, vii. 8. Sidman JD, Wheeler WB, Cabalka AK, Soumekh B, Brown CA, Wright GB. Management of acute pulmonary hemorrhage in children. Laryngoscope 2001;111(1):33-5. 9. Heslet L, Nielsen JD, Levi M, Sengelov H, Johansson PI. Successful pulmonary administration of activated recombinant factor VII in diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Crit Care 2006;10(6):R177. 10. Solomonov A, Fruchter O, Zuckerman T, Brenner B, Yigla M. Pulmonary hemorrhage: A novel mode of therapy. Respir Med 2009. 11. Colin AA, Shafieian M, Andreansky M. Bronchoscopic Instillation of Activated Recombinant Factor VII to Treat Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage in a Child. Pediatr Pulmonol 2009;In Press. 12. Saeed MM, Woo MS, MacLaughlin EF, Margetis MF, Keens TG. Prognosis in pediatric idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis. Chest 1999;116(3):721-5. 13. Le Clainche L, Le Bourgeois M, Fauroux B, et al. Long-term outcome of idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis in children. Medicine (Baltimore) 2000;79(5):318-26.