outcome of anatomic hepatic resection in patients with severe liver

advertisement

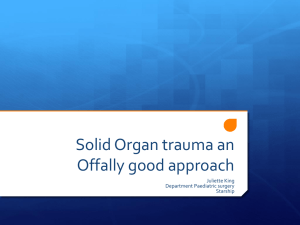

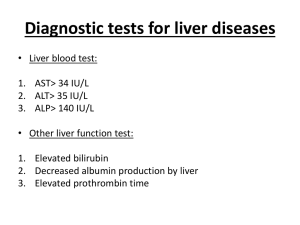

EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 17, NO. 1, JAN., 2006 Aly et al ______________________________________________________________________________________ OUTCOME OF ANATOMIC HEPATIC RESECTION IN PATIENTS WITH SEVERE LIVER TRAUMA By Moatasem M. Aly, Zaghloul N.M., Tohamy A. T., Tarik Abdel Azeez Ahmed, Khaled M. Mahran, Abou-Bakr Mohei El-Din. Department of Surgery, El-Minia Faculty of Medicine ABSTRACT: Background: The liver is the organ most commonly injured during abdominal trauma. The use of anatomic resection for liver trauma is advocated a conservative surgical approach when operative intervention is required. Objective: To assess the results of anatomic liver resection for severe liver trauma. Patients and Methods: During the period 2003 to 2005, among 100 patients with abdominal trauma and different types of liver injury admitted at El-Minia University Hospital, 20 patients had severe liver injuries and underwent anatomical hepatic resection. All patients had grade IV injury. Pringle maneuver was applied to control hemorrhage. The resections performed included, bi-segmentectomy of segment 6 and segment 7 (n = 8), left lateral segment resection (n = 6), right lobectomy (n = 4) and segmental resection of segment 6 (n = 2). Results: The mortality rate was 5%, as one patient died postoperatively due to major hepatic vein injury, while the morbidity rate was 25%. Postoperatively, there was a statistically significant improvement in hemodynamic status. One month after surgery, there was statistically non significant minimal change in liver functions. Conclusion: An anatomic resection of the liver for trauma in appropriate situations may be a useful, safe procedure today. KEYWORDS: Anatomic resection Severe liver trauma. operative measures to the use of extensive surgical techniques3. Surgical strategy for liver trauma is based on the extent and localization of the injury, the patient's overall status and severity of associated injuries. Resection of the injured parenchyma is indicated when laceration of a hepatic lobe occurs4. Progress of diagnostic human’s liver imaging (ultrasound, computerized tomography, magnetic nuclear resonance, etc.) stimulates development of modern liver surgery. Therefore, before and during the operation, surgeons and INTRODUCTION: The liver is the organ most commonly injured during abdominal trauma1. Liver trauma is the main cause of death in patients suffering abdominal injury, and remains an unresolved problem, especially in its most severe forms. Liver trauma, the main cause of death in patients suffering abdominal injury, remains an unresolved problem, especially in its most severe forms2. Management of hepatic trauma has been refined and ranges from non- 213 EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 17, NO. 1, JAN., 2006 Aly et al ______________________________________________________________________________________ radiologists can determine the site and extent of liver damage, its relationship with blood vessels and ascertain which part of the liver should be resected5. PATIENTS AND METHODS: During the period 2003 to 2005, among 100 patients with abdominal trauma and different types of liver injury admitted at El-Minia University Hospital, 20 patients had severe liver injuries and underwent anatomical hepatic resection. The admission hemodynamic data and physical examination findings included the initial emergency evaluation based on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), systolic blood pressure, pulse, and the presence of abdominal pain and tenderness. Hemodynamically stable patients were submitted for abdominal ultrasound, CT abdomen, and laboratory investigation particularly hematocrite measurement. Hepatic injury was graded either operatively or by CT according to the Hepatic Injury Scale established by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma13. All patients had grade IV injury in whom there was an evidence of ruptured intraparenchymal hematoma with active bleeding and parenchymal disruption involving 25–50% of the hepatic lobe. A single, worldwide-accepted classification of the liver still does not exist. Clinicians use Couinaud’s segmentation system for the smallest parts of the liver. It is important to localize small lesions before a segmentectomy with preservation of undamaged liver parenchyma, for example, in a setting of cirrhosis. However, some opine that Bismuth’s classification offers a sufficiently detailed level for description of anatomy involved in modern hepatic surgery and radiology6. H. Bismuth suggests dividing the liver into left and right livers (hemilivers). A right portal scissura divides the right liver into two sectors. Each sector has two segments: right anteromedial sector – segment V anteriorly and segment VIII posteriorly; right posterolateral sector – segment VI anteriorly and VII posteriorly. This is simple and practical for imaging studies of the liver (ultrasound, computed tomography or magnetic nuclear resonance)7,8. Laparotomy was done with Jshaped right subcostal incision, which was extended to midline when needed. The extent of hepatic injury was assessed Mobilization of the liver was done by dividing the falciform ligament, triangular and coronary ligaments. This to deliver the liver down. started by forceps fracture technique. To control hepatic hemorrhage, Pringle maneuver was applied, which includes 15 minutes clamping of portal triad followed by 5 minutes reperfusion. The resections performed included, bi-segmentectomy of segment 6 and segment 7 (n = 8), left lateral segment resection (n=6), right lobectomy (n=4) and segmental resection of segment 6 (n = 2), (Fig. 1). Segmental resections have been developed thanks to a better knowledge of hepatic anatomy and the increased use of intraoperative ultrasound9. Anatomic hepatic resection for trauma is associated with low mortality and liver-related morbidity rates and successfully addressed bleeding, devitalized parenchyma, and intrahepatic bile duct injuries when performed by experienced hepatobiliary surgeons1,10,11,12. The purpose of this study was to assess the results of anatomic liver resection for severe liver trauma. 214 EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 17, NO. 1, JAN., 2006 Aly et al ______________________________________________________________________________________ After resection and hemostasis, tubal drains were inserted followed by wound closure. Postoperative assessment of liver functions was done for all patients. mean ± SD (standard deviation), while discrete variables were expressed as number and percent (%). Statistical analyses were performed using t-student test for continuous variables. Analysis was done using Stat-view software SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). P-value was considered significant if <0.05, and highly significant if <0.001. Demographic, clinical, operative, and postoperative data were collected and analyzed. Continuous variables were expressed as data are presented as the Segemtecomy of segment 6 10% Right lobectomy 20% Bi-segmentectomy 40% Left lateral segmentectomy 30% Fig 1. Operative procedures in the studied patients. Postoperatively, there was a statistically significant improvement in hemodynamic status; systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), serum hemoglobin, and hematoctrit percent, when compared to preoperative values, (Table 4). Mean values of postoperative liver functions including levels of ALT, AST, bilirubin (direct and total), serum albumin were within normal values in most of the studied patients. One month after surgery, there was statistically non significant minimal change in liver functions (p-value >0.05), (Table 5). RESULTS: The twenty patients underwent anatomical hepatic resection, had mean age of 35.5±18.5 years, mean ISS of 21±8, and mean GCS of 12.2±3, (Table 1). Regarding operative data (Table 2), mean operative time was 75.2±28.5 minutes, and mean blood loss was 650±310 cm3. The mortality rate was 5%, as one patient died postoperatively due to major hepatic vein injury, while the morbidity rate was 25%, which included pneumonia in 2 patients (10%), abdominal wound infection in another 2 patients (10%), and subphrenic abscess in one patient (5%), (Table 3). 215 EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 17, NO. 1, JAN., 2006 Aly et al ______________________________________________________________________________________ Table 1: Demographic and clinical data of the study population. Parameter Age (years) Mean ± SD 35.5±18.5 GCS 12.2±3 SD: standard deviation, GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale. Table 2: Operative data. Parameter Operative time (min.) Blood loss (mL) SD: standard deviation. Mean ± SD 75.2±28.5 650±310 Table 3: Postoperative outcome. Parameter Mortality rate Morbidity rate: - Pneumonia - Abdominal wound infection - Subphrenic abscess No.(%) 1 (5%) 5 (25%) 2 (10%) 2 (10%) 1 (5%) Table 4: Baseline versus postoperative vital signs, serum hemoglobin and hematocrit value. Parameter Pulse (beat/min.) SBP (mmHg) DBP (mmHg) At admission 108.3±19.4 88.2 15.1 60.5 16.09 Postoperative 76±8.2 ** 110 11.47 ** 72.25 8.02 * 9.2±3.4 32±6.8 12.1±4.6 * 43.1±7.4 ** Serum hemoglobin (g/dl) Hematocrit (%) *: p-value <0.05. **: p-value <0.001. Table 5: Follow-up of liver functions after anatomic resection of the liver. Parameter One month after operation (N=19) AST (U/L) ALT (U/L) Total bilirubin (mg/dl) Immediately postoperative (n=20) 26.40±3.92 23.26±9.17 1.24±0.66 Direct bilirubin (mg/dl) Serum albumin (g/dl) 0.60±0.24 3.64±0.71 0.67±0.33 3.86±0.92 216 27±4.2 28±6.4 1.31±0.45 EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 17, NO. 1, JAN., 2006 Aly et al ______________________________________________________________________________________ left lobe resection segment VI, VII resection Hepatic resection plays a major role in the treatment of severe liver contusion, especially for patients with severe contusions in multiple places, and injuries in bile ducts, hepatic veins, and the inferior vena cava in combination with extensive parenchymal damage22. The anatomic resection has two main goals: (1) eradicating the source of bleeding; and (2) removing the site of necrosis. It leaves a smooth resected surface, with a viable liver and a low propensity for septic complications. However, it is not optimal treatment for all liver injuries and should never be used when simpler methods can achieve a successful outcome. The surgical procedure chosen must be appropriate for the individual injury, the patient, and the surgeon in attendance. Broad condemnation of an anatomic resection as a useful treatment modality has resulted in less than adequate surgery for the shattered-liver injury 1. DISCUSSION: The common frequency of liver injuries in modem society is a reflection of the transition to mechanized transportation as well as a progressive increase in violent behavior14. Severe liver injuries carry high morbidity and mortality ranging between 40 and 80%15. Non-operative therapy of liver injuries has become an acceptable approach to management of hemodynamically stable patients without associated injury requiring laparotomy, and the indication is extended16–20. However, Parks and some other surgeons recommend that nonoperative management should be initiated only for injuries below grade III in patients with stable hemodynamics; grade III to grade V injuries usually require surgical intervention21. Strong et al.,11 have an active attitude and recommend anatomic resection for severe liver trauma. We agree with the viewpoints of Parks and Strong; in our opinion, vital signs of patients (pulse, blood pressure, etc.) are critical in deciding whether nonoperative management can be applied. In other words, surgical intervention is mainly indicated by unstable hemodynamics. In the present study, we used Hepatic Injury Scale established by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma13, to select patients with severe liver injury for anatomic resection. This 217 EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 17, NO. 1, JAN., 2006 Aly et al ______________________________________________________________________________________ scoring system for liver injuries represents a logical synthesis of prior scaling systems predominantly that originally described by Moore and coworkers23. Grades III through VI are generally considered severe liver injuries. The utility and validity of this scale was addressed in clinical studies24. mortality and morbidity rates are agreed with more recent studies as reported Strong et al.,11 who reported that an anatomic hepatic resection for trauma is associated with low mortality and liver related morbidity rates when performed by experienced hepatobiliary surgeons, and that its role in the management of severe hepatic trauma should be reevaluated. Those authors reported the overall mortality rate of 8.1%11. Also, in the study by Tsugawa et al.,1 the mortality rate was 21.1% among young patients and 27.6% among elderly. The better results obtained in our study and the studies by Strong et al.,11 and Tsugawa et al.,1 may be explained by the better understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the liver, improved anesthetics and postoperative care, and advances in operative techniques in the last two decades. We used Pringles' manoeuvre (temporary occlusion of the hepatic artery and portal vein) to control hepatic hemorrhage. Various protocols have been recommended using periods of inflow occlusion for 10 to 30 minutes followed by 5 to 15 minutes of reperfusion. Elias et al.,25 demonstrated that the intermittent Pringle maneuver results in less blood loss and better preservation of liver function and permits a total ischemia time of up to 120 minutes. A randomized clinical study of patients undergoing liver resection by Belghiti et al.,26 showed that intermittent clamping using multiple cycles of 15 minutes of ischemia and 5 minutes of reperfusion was associated with decreased injury compared with similar periods of continuous inflow occlusion. Therefore, an anatomic resection for trauma in appropriate situations may thus be a useful, safe procedure today, as surgeons now have a better understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the liver and can use improved anesthetics postoperative care, and the advances in operative techniques. The present study revealed an acceptable morbidity and mortality rates, without major deterioration of liver function immediately, and one month after surgery. Our mortality rate was 5%, and the morbidity rate was 25%. REFERENCES: 1- Tsugawa K, Koyanagi N, Hashizume M, Ayukawa K, Wada H, Tomikawa M, Ueyama T, Sugimachi K. Anatomic resection for severe blunt liver trauma in 100 patients: significant differences between young and elderly. World J Surg. 2002;26(5):544-9. 2- Gao JM, Du DY, Zhao XJ, Liu GL, Yang J, Zhao SH, Lin X. Liver trauma: experience in 348 cases. World J Surg. 2003;27(6):703-8. 3- Ringe B, Pichlmayr R. Total hepatectomy and liver transplantation: a Some publications discouraged anatomic resection in liver trauma due to reported mortality rates above 50%27,28. Also, the high rates of morbidity in early studies due to persistent hemorrhaging and subphrenic septic complications appear to be some of the negative results of this policy29,30. However, our low 218 EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 17, NO. 1, JAN., 2006 Aly et al ______________________________________________________________________________________ life-saving procedure in patients with severe hepatic trauma. Br J Surg. 1995;82(6):837-9. 4- Vyhnanek F, Denemark L, Duchac V. Current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in liver injuries. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2003;70(4):219-25. 5- Rutkauskas S, Gedrimas V, Pundzius J, Barauskas G, Basevicius A. Clinical and anatomical basis for the classification of the structural parts of liver. Medicina (Kaunas). 2006; 42(2): 98-106. 6- Soyer P. Segmental anatomy of the liver: utility of a nomenclature accepted worldwide. AJR. 1993;161: 572-3. 7- Bismuth H. Surgical anatomy and anatomical surgery of the liver. World J Surg. 1982;6:3-9. 8- Bismuth H. A text and atlas of liver ultrasound. London: Chapman and Hall Medical; 1991. p. 2-15. 9- Chouillard E, Cherqui D, Tayar C, Brunetti F, Fagniez PL. Anatomical biand trisegmentectomies as alternatives to extensive liver resections. Ann Surg. 2003;238(1):29-34. 10- Hollands MJ, Little JM. The role of hepatic resection in the management of blunt liver trauma. World J Surg. 1990;14(4):478-82. 11- Strong RW, Lynch SV, Wall DR, Liu CL. Anatomic resection for severe liver trauma. Surgery. 1998; 123(3):251-7. 12- Lee TY, Chen YL, Chang HC, Yang LH, Chan CP, Chen ST, Kuo SJ. Anatomic resection for severe blunt liver trauma. Int Surg. 2005;90(5):266-9. 13- Moore EE, Shackford SR, Pachter HL. Organ injury scaling: spleen, liver, kidney. J. Trauma 1989; 29: 1664. 14- Reed RL, Merrell RC, Meyers WC. Continuing Evolution in the Approach to Severe Liver Trauma. Ann Surg. 1992;216(5):524-36. 15- Gonzalez-Castro A, Suberviola Canas B, Holanda Pena MS, Ots E, Domínguez Artiga MJ, Ballesteros MA. Liver trauma. Description of a cohort and evaluation of therapeutic options. Cir Esp. 2007;81(2):78-81. 16- Boone DC, Federle M, Billiar TR. Evolution of management of major hepatic trauma: identification of patterns of injury. J Trauma 1995;39:344–350. 17- Brasel KJ, Delisle CM, Olson CJ. Trends in the management of hepatic injury. Am. J. Surg. 1997;174:674–677. 18- Pachter HL, Knudson MM, Esrig B,. Status of nonoperative management of blunt hepatic injuries in 1995: a multicenter experience with 404 patients. J. Trauma 1996;40:31–38. 19- Sherman HF, Savage BA, Jones LM. Nonoperative management of blunt hepatic injuries: safe at any grade? J. Trauma 1994;37:616–621. 20- Meredith JW, Young JS, Bowling J. Nonoperative management of blunt hepatic trauma: the exception or the rule? J. Trauma 1994;36: 529–535. 21- Parks RW, Chrysos E, Diamond T. Management of liver trauma. Br. J. Surg. 1999;86:1121–1135. 22- Gourgiotis S, Vougas V, Germanos S, Dimopolous N. Operative and nonoperative management of blunt hepatic trauma in adults: a single-center report. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007; 14:387–391. 23- Moore EE, Shackford SR, Pachter HL. Organ injury scaling: spleen, liver, and kidney. J Trauma 1989; 29:1664-1666. 24- Croce MA, Fabian TC, Kudsk KA. AAST Organ Injury Scale: correlation of CT-graded liver injuries 219 EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 17, NO. 1, JAN., 2006 Aly et al ______________________________________________________________________________________ and operative findings. J Trauma 1991; 31:806-812. 25- Elias D, Desruennes E, Lasser P. Prolonged intermittent clamping of the portal triad during hepatectomy. Br J Surg. 1991;78:42-44. 26- Belghiti J, Noun R, Malafosse R. Continuous versus intermittent portal triad clamping for liver resection. Ann Surg. 1999;229:369-375. 27- Beal SL. Fatal hepatic hemorrhage: an unresolved problem in the management of complex liver injuries. J. Trauma 1990; 30:163–169. 28- Fabian TC, Croce MA, Stanford GG. Factors affecting morbidity following hepatic trauma. Ann. Surg. 1991;213:540–547. 29- Feliciano DV, Mattox KL, Burch JM. Packing for control of hepatic hemorrhage. J. Trauma 1986;26:738– 743. 30- Ivatury RR, Nallathambi M, Gunduz Y. Liver packing for uncontrolled hemorrhage: a reappraisal. J. Trauma 1986;26:744–753. 220 EL-MINIA MED., BULL., VOL. 17, NO. 1, JAN., 2006 Aly et al ______________________________________________________________________________________ دراسة نتائج االستئصال الجزئي للكبد في مرض تهتك الكبد الناتج عن الحوادث معتصم محمد علي ،ناصر محمد زغلول ،تهامي عبدهللا ، طارق عبدالعزيز أحمد ،خالد مهران ،أبو بكر محي الدين قسم الجراحة العامة – كلية طب المنيا إن الكبد بين األعضاء المعرضة لإلصابة أثناء التعرض إلصابات البعض في الحوادث وإن استخدام األسلوب التشريحي لتقسيم الكبد إلي وحدات واستئصال الكبد بناء عليه قد أدخل فكرة الجراحة التحفظية للكبد عند الحاجة لذلك ،لهذا تم عمل هذا البحث لتقييم نتائج استخدام هذا األسلوب في حاالت الحوادث . وقد أجريت هذه الدراسة في الفترة من يناير – 2003يناير ، 2005في قسم االستقبال والحوادث بمستشفي المنيا الجامعي ،وشملت هذه الدراسة ( ) 100مريض يعانون من إصابات البطن وإصابات مختلفة للكبد ،وتم تحديد 20مريضا ً يعانون من تهتك شديد بأحد فصوص الكبد ويحتاجون لجراحة وهؤالء المرضي يصنفون من الدرجة ، IVحيث تضيف الجمعية األمريكية لجراحة الكبد . ويتم إدراج المرض للجراحة بعد عمل الفحوص المعملية الالزمة وتقييم الحالة العامة للمريض وكذلك أجزاء أشعة تليفزيونية ومقطعية للكبد لتحديد مدي اإلصابة في الكبد وتم استخدام طريقة برنجل للسيطرة علي تيار الدم الداخل للكبد أثناء إجراء القطع لألنسجة ،وتم إجراء استئصال الوحدة 7 ، 6من الكبد في عدد ( )8مرض ،الجزء الخارجي للفص األيسر وحده 3 ، 2في عدد ( )6مرضي واستعمال الفص األيمن في عدد ( )4مرضي واستئصال وحدة واحدة رقم 6في عدد ( )2مرضي. وتمت الجراحة بنجاح في % 95ممن المرضي مع حدوث حالة وفاة واحدة ناتجة عن تهتك شديد في أوردة الكبد الرئيسية ،وحدوث مضاعفات مرضية شديدة في الدورة الدموية بعد إجراء الجراحة . ولذلك لم يحدث أي تغيير ملحوظ في وظائف الكبد عن طريق متابعتها لمدة شهر بعد الجراحة . لذلك يعتبر االستئصال المبني علي أسس تشريحية للكبد في حاالت الحوادث وسيلة آمنة وسريعة ويسهل استخدامها في الظروف الطارئة . 221