COMMON COMPLICATIONS OF DENTOALVEOLAR SURGERY

advertisement

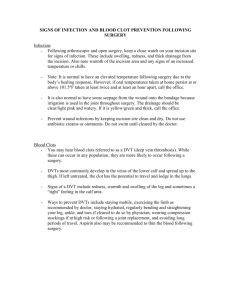

COMMON COMPLICATIONS OF DENTOALVEOLAR SURGERY: BLEEDING & INFECTION OBJECTIVES 1. That the student is able to place complications within the context of surgical trauma, normal healing and expected sequelae. 2. That the student is able to recognize abnormal bleeding as a complication, diagnose the nature and extent of the problem and deal with it in a timely and effective manner. 3. That the student is able to recognize infection as a complication, diagnose the nature and extent of the problem and deal with it in a timely and effective manner. 1. CONTROLLED SURGICAL TRAUMA (the application of force): For the most part, DENTOALVEOLAR surgery means the removal of teeth. The removal of teeth requires the application of force to the tooth and its supporting structures and the infliction of controlled traumatic damage to the tissues. This damage to periodontal ligament, tooth and / or bone results in the loosening of the tooth and ultimately allows for its removal. The amount of force and in what direction and therefore how much trauma is inflicted are dependent on a wide range of factors. These factors include the condition and shape of the tooth, the amount and density of the bone, the available access to the tooth in question, the instruments available and the skill and experience of the operator. These technical issues are superimposed onto the underlying biological status of the patient and then finally affected by the environmental conditions that exist prior to, during and after surgery. All of these issues conspire to produce, in any given patient, their dental surgical "experience". It is during the unfolding of this experience that both normal post-operative sequelae as well as complications occur. 2. SEQUELAE ( what we expect): The normal post-operative sequelae for any patient for any procedure include pain, bleeding, swelling, trismus and possibly bruising. These things are normal and given the biology of what is occurring should be expected by both the patient and the surgeon. When the duration or intensity of any of these things exceed the expected they start to fall into the range of complications. We must therefore determine our expectations prospectively for both ourselves and for the patient so that both of us know when something is wrong and that something must be done. For the most part this process is simple. We look at a tooth, determine the degree of difficulty and decide that the patient will be sore for so many days and then advise and prescribe accordingly. The procedure is performed, the patient dismissed and usually normal healing occurs. This healing usually progresses from clot formation and acute inflammation to granulation and, eventually, ossification in an orderly fashion. When patient, operator or environmental factors disrupt this process we see an alteration in this stately progression and we declare that we have a complication. 3. COMPLICATIONS (when things go wrong): Two of the main complications of concern to the dental surgeon include bleeding and infection. Complications require evaluation of risk, prevention, recognition of occurrence and therapeutic intervention that is particular to the problem. The best way to deal with any complication is to prevent it in the first place. This is based on the knowledge of the underlying biological processes in combination with a knowledge of the patient. Once the complication has occurred, recognition is critical and this is, as always, based on the combination of historical and clinical findings or signs and symptoms unique to a given complication. Having diagnosed a problem through recognition, the treatment plan is drawn up and this usually combines medications with procedures and ultimate follow up. A. Bleeding a) Evaluation of risk and prevention: The coagulation process involves a complex interplay of clotting factors, cellular components and blood vessels. These come together to plug the hole created by the extraction of a tooth. At the risk of over-simplification, the entire process comes down to the formation of a fibrin-platelet complex that fills the gap. Risk evaluation involves knowing the factors that impinge on the normal functioning of these processes. The possibility of poor platelet or factor performance will be recognized by a drug history, a history of spontaneous or easy bruising or formation of petechiae, a history of prolonged bleeding following previous surgery or injury or a family history of bleeding disorders. The risk factors that affect platelet formation include drug effects such as aspirin or low platelet count brought on by chemotherapy or immune thrombocytopenia. Low platelet numbers will be detected by a CBC (Complete Blood Count) but functional defects can only be screened for with a bleeding time. Lower factor levels are associated with inherited disorders such as hemophilia, liver disorders such as alcoholic cirrhosis, vitamin K deficiency brought on by chronic antibiotic use and the use of anticoagulant drugs such as coumadin and heparin. These considerations indicate specific tests such as INR (International Normalized Ratio for PT (Prothrombin Time)) and PTT (Partial Thromboplastin Time) or pre-operative consultation with a haematologist. Identification of risk factors allows the appropriate modification to the treatment plan. These include platelet or factor transfusion and alteration to the overall plan such as removal of one tooth at a time rather than many all at once. b) Recognition: Should an undetected problem exist, it will normally be apparent right at the time of surgery. Following tooth removal the surgeon will experience difficulty in achieving haemostasis and oozing will be prolonged. Post-operatively the clot will be fragile and prone to rebleeding. If the patient has successfully formed a clot, the greatest risk factor for secondary bleeding is mechanical trauma to the operative site. This may take many forms ranging from suction associated with smoking to rough edges of taco chips. Very often this post-op bleeding will take the form of a liver clot. This is recognized clinically by the presence of a hyperplastic clot spilling out of the socket and generally making a mess of things. This "liver clot" is very fragile and minimal mechanical disturbance will initiate rebleeding. c) Management: At the time of surgery or immediately after, mechanical aids to hemostasis are usually sufficient. This includes direct pressure, haemostatic sponges such as gel-foam and/or sutures. Delayed rebleeding most often necessitates the COMPLETE removal of the liver clot under local anaesthesia followed by pressure, packing and sutures. Rarely, significant bleeding will have an underlying physiological defect and these measures will be insufficient. If such is the case, haematological consultation with transfusion of platelets or factors may be necessary. Recall that the final common pathway in clot formation is the activation of fibrinogen by thrombin to form fibrin. Fibrinogen is typically NOT in short supply, the defect in clotting is related to a failure to form thrombin either as a function of drugs (coumadin) or factor deficiency (hemophilia). Therefore supplying thrombin topically to the bleeding wound will result in localized clot formation. Topical thrombin (Thrombostat) is available through emergency departments and is easily used. The powder is reconstituted with saline and the solution is used to soak gel-foam sponges which are then sutured in place. B. Infection: Post-operative wound infections come in a variety of forms each of which has its own pattern of timing, clinical signs and associated problems. Interestingly, all of these varieties have a common list of risk factors and potential preventative measures. a) Risk assessment and prevention: The risk of post-op infection is increased with smoking, poor oral hygiene, pre-existing infection (such as peri-apical or pericoronal disease) and with generalized immunocompromise such as seen in AIDS patients, diabetics or with chemo-therapy. Prevention involves eliminating as many risk factors as possible. Cessation of smoking, oral hygiene instruction and pre-operative elimination of acute infection combined with efficient surgery, minimal trauma and thorough wound debridement will all help to decrease the risk of post-op infection. The role of "prophylactic" antibiotics continues to be controversial given the extreme difficulty in performing studies of their efficacy. b) Recognition: i. Acute hemolytic: This is the typical dry socket and it is difficult to truly call this an infection. It is a result of host mediated or microbiologically mediated fibrinolysis or degeneration of the blood colt. This then leads to the exposure of the naked walls of the bony socket to the bacteria in the saliva with resultant severe, radiating pain entirely out of proportion to clinical signs. There is usually minimal swelling and minimal inflammation. There is often, however, a characteristic foul odour combined with a socket full of food debris. ii. Acute suppurative: these infections are much less common and lead to early severe abscess formation. These are often related to exacerbation of preexisting infection and can be very severe. In contrast to dry sockets, these are characterized by severe swelling, pain, fever, trismus, and rapid spread. iii. Chronic suppurative infections take the form of a sub-periosteal abscess. These typically appear two to four weeks following surgical socket. The patient tends to give a history of initial uneventful healing, then a two to three day period of vague pain followed by hard swelling in the vestibule and point tenderness. iv. Chronic sclerosing infections following tooth extractions are rare. These infections can be extensive and very resistant to management. They are characterized by long term discomfort with minimal swelling, occasional acute exacerbations and display sometimes extensive radiographic changes. c) Management: i. Acute haemolytic: The dry socket is managed by initial debridement followed by sedative dressing. Occasionally, this may require one or more retreatments. Analgesics are sometimes necessary, but often irrigation and dressing of the socket will bring instantaneous relief. ii. Acute suppurative: Infections of post-operative extraction wounds require early aggressive treatment. If associated with a surgical extraction that involved the raising of a flap, these can spread very rapidly along the surgically opened tissue planes. When abscess formation occurs, the treatment involves incision and drainage with a swab for culture and sensitivity test for the causative organisms. Without a C and S result, antibiotic failure will leave the clinician in the dark as to the next best choice. In conjunction with an I and D, the patient is started on antibiotics. My personal preference is a combination of Penicillin and Flagyl. Both are bacteriocidal and complement each other's range of killing. Penicillin is very effective against the oral Streptococcal species and Flagyl is effective against anaerobes. The patient is also given an analgesic for pain relief and, if necessary, fluid support. In all cases, patients should be reassessed in 24 hours for progression or resolution. Drains should be removed when drainage ceases, usually within two to four days. These patients may respond rapidly or slowly, and, for this reason, follow up is necessary. For the more serious infections, hospitalization may be required for airway support, intravenous antibiotics or extensive surgery. Indications for more aggressive management include the following: a) b) c) d) significant trismus significant odynophagia dysphagia dyspnea e) elevation of the tongue f) deviation of the uvula g) bilateral swelling h) rapid severe swelling i) chest pain j) obvious systemic toxicity k) obvious systemic toxicity l) eye signs m) clouding or loss of consciousness iii. Chronic suppurative: Subperiosteal abscesses tend to be localized to the subperiosteal space. For this reason, the patients are less acutely ill and much easier to manage than a full blown wound abscess. Typically the area can be probed, drained and irrigated with excellent results. Occasionally, these patients require incision and drainage, culture and sensitivity, antibiotic analgesics and follow-up with drain removal in one to three days. These patients tend to respond very rapidly to treatment. iv. Chronic sclerosing: Fortunately, these infections following tooth extractions are very rare. Often these require operative intervention involving sequestrectomy or extensive removal of infected and necrotic bone. Unfortunately, this may be extensive and require wide excision including hemimandibulectomy.