Epistaxis - developinganaesthesia

advertisement

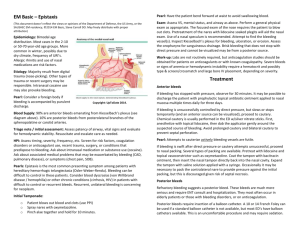

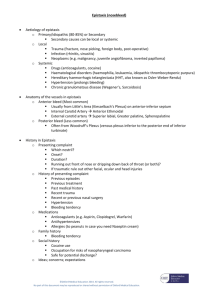

EPISTAXIS Introduction Epistaxis is a common presenting problem to the ED. Most cases will be spontaneous idiopathic, but occasionally there may be more serious underlying pathology. Management in the ED will consist of: ● Controlling the bleeding ● Ruling out potential serious underlying disease ● Deciding on the most appropriate disposition plan Epidemiology There are bimodal distribution peaks ● Between the ages of 2-10 years. ● Between the ages of 50-80 years. Pathology Causes: 1. Most cases are spontaneous idiopathic Less commonly: 2. Trauma (see also “Nasal Fractures” guidelines) 3. Coagulopathies: ● Intrinsic disease ● Medication related, (aspirin, warfarin or NOACs) 4. Tumors 5. Vascular lesions: ● Hereditary telangiectasias ● A-V malformations 6. Infection (uncommonly) 7. Allergic rhinitis 8. Illicit drug related: ● Solvent inhalation ● Cocaine snorting Note that traditionally hypertension has been quoted as a factor, but although elderly patients may often be found to have hypertension (and this may be partially explained by acute distress), a direct causal relationship with epistaxis has never been clearly demonstrated. Clinical assessment 1. Assess the patient's airway 2. Assess the patients vital signs 3. Try to identify a source or site of bleeding. ● Gentle use of a nasal speculum and a good light source will assist. ● Establish the side of the bleeding, (not always possible in the ED) ● Establish whether bleeding is from an anterior source (bleeding is most commonly from Little’s area - see appendix 1 below) or a posterior source? Failure to locate an anterior source, will suggest a posterior source for the bleeding. Investigations Usually none are routinely necessary, unless there has been significant blood loss and/ or significant underlying pathology is suspected. Consider: ● FBE ● Clotting profile ● MRI may be considered if a local nasopharyngeal lesion is suspected. Management 1. Attention to any immediate ABC issues: ● 2. May require IV fluids, blood cross match if necessary. First aid measures: Direct pressure on the lower compressible part of the nose for at least 10 minutes. 3. ● Pressure at the root of the nose, ie over the (non-compressible nasal bones) is not effective. This is a very common “lay” misconception. ● Patient should sit up and lean forward (not “tilt the head back” - and aspirate the blood!). ● Blood should be spat out, not swallowed, (blood is irritating to the stomach and may result in vomiting). Sedation: ● 4. Cophenylcaine forte: ● 5. IV morphine with metoclopramide is often useful for distressed patients. Cophenylcaine forte nasal spray can be used to anaesthetise the mucosa and as a vasoconstrictor to help reduce bleeding. Cauterization: Silver nitrate sticks: If an anterior bleeding point is seen, then cauterization with a silver nitrate stick may be tried ● Moisten the tip of the stick in normal saline, and then apply directly to the bleeding region of nasal mucosa. ● Brush the tip of the silver nitrate stick over Little's area until a greyish eschar occurs. ● Generally only one septum should be cauterized using silver nitrate, as bilateral cauterizations may predispose to a sepal perforation. Electrocautery: ● 6. This is an additional options that may be used by an ENT surgeon. Nasal Packing: If direct pressure fails to adequately stop bleeding then nasal packing will be necessary. This should be done for both sides if the site of bleeding is uncertain. Be sure to wear a gown - blood can be liberally splattered when a patient coughs or gags! Provide the patient with a kidney dish, to periodically spit out blood when required Gentle suction may be helpful There is a range of packing options available, including: Haemostatic packing materials: ● Algoderm, (sterile calcium alginate rope), may be used, this material helps promote hemostasis. ● Xeroform (BIPP gauze) ribbon is another alternative. Nasal tamponading devices: Use Coephylcaine forte nasal spray before packing Options include: ● Merocel nasal tampon. ● Brighton Epistaxis device, (see separate guidelines) ● Foley catheters have been used in emergencies, when no more appropriate device is available, (10-14 French with 30ml balloon). Nasal tamponading and haemostatic devices: ● The Rapid Rhino nasal packing device, although more expensive to use than other methods this is currently the best available device for the control of epistaxis, (see separate guidelines) ● It can be used for both anterior and posterior nasal packing. Packs are usually left in for 48-72 hours, though with the Rapid Rhino devices, 24 hours is usually sufficient. Broad spectrum antibiotics are usually given as serious infection, particularly in the form of Toxic Shock Syndrome, is possible in the setting of packing. 7. Tranexamic acid: Tranexamic acid is another option in severe cases of epistaxis. It is a potent competitive inhibitor of plasminogen activator and thus of the fibrinolytic system, and so may help prevent clot dissolution as well as reduce the likelihood of re-bleeds. 9. Surgery: Uncontrolled and severe epistaxis may require surgical ENT intervention. ● Endoscopic guided cautery ● Arterial ligation of ethmoidal arteries or even external carotid artery in extreme emergencies. ● Angiography and vessel embolization is a further option. Disposition: Younger patients with spontaneous bleeds may be discharged if well. Antibiotics should be given and the patient reviewed in 24 hours for removal of packs or devices. Admission may be required for: ● Patients with coagulopathies ● Patients who required fluid resuscitation ● Patients with significant co-morbidities ● Patients with significant social problems that may interfere with their ability to cope. ● A significant underlying pathology is suspected. ● Threshold for admission for a period of observation should always be low for elderly patients. An SSU admission is usually sufficient. Failure to adequately control bleeding requires urgent referral/ consultation with the ENT surgeon. Recurrent episodes of epistaxis (especially if unilateral) in older patients should prompt an ENT referral to rule out a possible serious underlying lesion. Appendix 1 Little's Area: Three arteries form a vascular anastomosing plexus of vessels in the mucosa, that covers the quadrilateral cartilage of the septum anterior to the nasal valve. The plexus is known as Kiesselbach’s Plexus, and the region where it is located is known as Little's area. It is the most common site of anterior nose bleeds. References 1. Middleton PM; Epistaxis; EMA Oct-Dec16 2004 (5-6): 428-40. Dr J. Hayes Reviewed June 2012.