EPISTAXIS - EDventures

advertisement

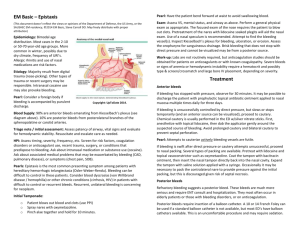

EPISTAXIS Introduction Epistaxis is a common presenting problem to the ED. Most cases will be spontaneous and idiopathic, but occasionally there may be more serious underlying pathology. Management in the ED will consist of: ● Controlling the bleeding ● Ruling out potential serious underlying disease ● Deciding on the most appropriate disposition plan Epidemiology There are bimodal distribution peaks ● Between the ages of 2 -10 years. ● Between the ages of 50 - 80 years. Pathology Causes: 1. Most cases are spontaneous and idiopathic. 2. Trauma (see also “Nasal Fractures” Document) Less commonly: 3. Coagulopathies: ● Intrinsic disease ● Medication related, (aspirin, warfarin or NOACs) 4. Tumors 5. Vascular lesions: ● Hereditary telangiectasias ● A-V malformations 6. Infection (uncommonly) 7. Allergic rhinitis 8. Illicit drug related: ● Solvent inhalation ● Cocaine snorting Note that traditionally hypertension has been quoted as a factor, but although elderly patients may often be found to have hypertension (and this may be partially explained by acute anxiety and distress), a direct causal relationship with epistaxis has never been clearly demonstrated. Clinical assessment 1. Assess the patient's airway 2. Assess the patients vital signs 3. Try to identify a source or site of bleeding. ● Gentle use of a nasal speculum and a good light source will assist. ● Establish the side of the bleeding, (not always possible in the ED) ● Establish whether bleeding is from: ♥ An anterior source (bleeding is most commonly from Little’s area see appendix 1 below) Or ♥ A posterior source Failure to locate an anterior source, will suggest a posterior source for the bleeding. Investigations Usually none are routinely necessary, unless there has been significant blood loss and/ or significant underlying pathology is suspected. Consider: 1. FBE 2. Clotting profile 3. MRI may be considered if a local nasopharyngeal lesion is suspected. Management 1. Attention to any immediate ABC issues: ● 2. May require IV fluids, blood cross match if necessary. First aid measures: ● Direct pressure on the lower compressible part of the nose for at least 10 minutes. Pressure at the root of the nose, i.e over the (non-compressible nasal bones) is not effective. This still remains a very common “lay” misconception. ● Patient should sit up and lean forward (not “tilt the head back” - and aspirate the blood!). ● Blood should be spat out, not swallowed, (blood is irritating to the stomach and may result in vomiting). See also Appendix 2 below for a “readymade” first aid device 3. Sedation: ● 4. Cophenylcaine forte: ● 5. IV morphine with metoclopramide or other antiemetic is often useful for distressed patients. Cophenylcaine forte nasal spray can be used to anaesthetise the mucosa and as a vasoconstrictor to help reduce bleeding. Cauterization: Silver nitrate sticks: If an anterior bleeding point is seen, then cauterization with a silver nitrate stick may be tried ● Moisten the tip of the stick in normal saline, and then apply directly to the bleeding region of nasal mucosa. ● Brush the tip of the silver nitrate stick over Little's area until a greyish eschar occurs. ● Generally only one septum should be cauterized using silver nitrate, as bilateral cauterizations may predispose to a sepal perforation. ● A slightly moistened cotton wool bud should then be packed into the nose in order to stop any silver nitrate containing secretions running out of the nose towards the lip, where damage can be done - a potential source of medical litigation! Electrocautery: ● 6. This is an additional options that may be used by an ENT surgeon. Nasal Packing: If direct pressure fails to adequately stop bleeding then nasal packing will be necessary. This should be done for both sides if the site of bleeding is uncertain. Be sure to wear a gown - blood can be liberally splattered when a patient coughs or gags! Provide the patient with a kidney dish, to periodically spit out blood when required Gentle suction may be helpful There is a range of packing options available, including: Nasal packing soaked in various solutions: ● Gauze ribbon packing: Generally a 15 cm length of ribbon is used, that is soaked in: ♥ Adrenaline and lignocaine: Adrenaline solution (1:10,000) and lignocaine (2%) for 10 minutes. Packing generally remains in for 24-72 hours. ♥ Tranexamic acid: 2 Use an ampoule of the 500mg in 5ml IV solution. It is a potent competitive inhibitor of plasminogen activator and thus of the fibrinolytic system, and so may help prevent clot dissolution as well as reduce the likelihood of re-bleeds. The ribbon can be removed after several hours when bleeding has ceased. Haemostatic packing materials: ● Algoderm, (sterile calcium alginate rope), may be used, this material helps promote hemostasis. ● Xeroform (BIPP gauze) ribbon is another alternative. Nasal tamponading devices: Use Coephylcaine forte nasal spray before packing Options include: ● Merocel nasal tampon. ● Brighton Epistaxis device, (see separate document) ● Foley catheters have also been used in emergencies, when no more appropriate device is available, (10-14 French with 30ml balloon). Nasal tamponading and haemostatic devices: ● The Rapid Rhino nasal packing device, although more expensive to use than other methods this is currently the best available device for the control of epistaxis, (see separate document) ● It can be used for both anterior and posterior nasal packing. Packs are usually left in for 48-72 hours, though with the Rapid Rhino devices, 24 hours is usually sufficient. Broad spectrum antibiotics are usually given as serious infection, particularly in the form of Toxic Shock Syndrome, is possible in the setting of prolonged packing. 9. Surgery: Uncontrolled and severe epistaxis may require surgical ENT intervention. ● Endoscopic guided cautery ● Arterial ligation of ethmoidal arteries or even external carotid artery in extreme emergencies. ● Angiography and vessel embolization is a further option. Disposition: Younger patients with spontaneous bleeds may be discharged if well. Antibiotics should be given and the patient reviewed in 24 hours for removal of packs or devices. Admission may be required for: ● Patients with coagulopathies ● Patients who required fluid resuscitation ● Patients with significant co-morbidities ● Patients with significant social problems that may interfere with their ability to cope. ● A significant underlying pathology is suspected. ● Threshold for admission for a period of observation should always be low for elderly patients. An SSU admission is usually sufficient. Failure to adequately control bleeding requires urgent referral/ consultation with the ENT surgeon. Recurrent episodes of epistaxis (especially if unilateral) in older patients should prompt an ENT referral to rule out a possible serious underlying lesion. Appendix 1 Anatomy: Little’s Area: Three arteries form a vascular anastomosing plexus of vessels in the mucosa, that covers the quadrilateral cartilage of the septum anterior to the nasal valve. The plexus is known as Kiesselbach’s Plexus, and the region where it is located is known as Little's area. It is the most common site of anterior nose bleeds. Appendix 2, The Buck Nasal Peg: Dr. Andrew Buck, demonstrates his clever tongue depressor first aid device for the control of anterior epistaxis, (with thanks to Dr Buck; at edexam.com.au). Continuous pressure to Little’s area for at least 10-20 minutes provides the best initial first aid for epistaxis. Patients themselves are often incapable of doing this properly because of anxiety or other reasons. Often they will only compress intermittently, and so merely promote further bleeding! Staff members in busy Departments can often ill afford the time to assist the patient. A nasal compression device serves as the best answer. Specific devices do exist, but are rarely stocked and available in EDs. A nasal peg device however can be readily fashioned by the simple use of two tongue depressors and some tape (always readily available in EDs) Tape is applied about 1/3 of the way down to the two tongue depressors - thus forming a “readymade” nasal peg - as demonstrated by the eminent Dr. Andrew Buck above! Now Dr Buck readily admits that this device can appear somewhat humorous when applied, but makes the good point that a little good humour can actually go a long way to relieving anxiety in a particularly anxious patient! The advantages of the “Buck Nasal Peg” - is that it frees the patient’s hands, frees them from the anxiety of having to provide their own first aid, and also frees staff to do other important tasks - perhaps inserting an IV for example or taking blood tests, or readying a more definitive device such as the "Rapid Rhino". A vasoconstrictor soaked gauze (e.g. cophenylcaine forte) packed into both nares can further assist in achieving haemostasis. The device can be further tightened if necessary by applying extra tape, further along the tongue depressors and re-applying this to the nares as again demonstrated by Dr Buck below. The device may also assist in diagnosis, in the sense that should the patient continue to bleed into the back of the mouth, - a posterior nasal bleeding source will be likely. References 1. Middleton PM; Epistaxis, EMA Oct-Dec16 2004 (5-6): 428 - 40. 2. Zahed R et al. A new and rapid method for epistaxis treatment using injectable form of tranexamic acid topically: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Emergency Medicine 31 (2013) 1389-1392. Dr J. Hayes Acknowledgments: Dr Mani Rajee Dr Andrew Buck Reviewed July 2015.