Multigrade teaching – reported patterns of work

advertisement

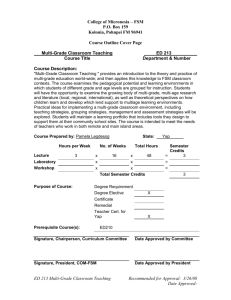

Overview of reported methods of teaching Multi-grade classes in the developing world Anita Pincas Draft - January 2007 These pages contain notes on chapters from Angela Little (ed), Education for All and Multi-grade Teaching: Challenges and Opportunities, Springer, 2006. See detailed references at end. An overall summary is provided in the Chart after these notes. The chapters of the book were written by specialists from a range of different countries in the developing world. Writers described aspects of their pedagogy in the classroom, as well as other issues related to multi-grade teaching. In these summaries, the pedagogic facts are included, with only brief indications of wider issues. Methodology comments (Turks and Caicos) In introduction points to a lot of examples of research that show that multi-grade teachers tend to teach grade by grade. ‘The most popular method is to teach a lesson to one group while the other group works on follow-up activities to previous instruction (individual seatwork)’. This means that pupils in multi-grade classes spend more time on independent work that pupils in mono-grade classes. Both types of class used same classroom organisation (pupils in rows facing the blackboard) with the exception of one multi-grade class. In multi-grade classes all pupils at same level sat together in an easily identifiable group (cf mixed ability mono-grade classes where pupils not usually grouped in this way) Multi-grade classes much more likely to have self-access materials in classroom – suggesting that self-access work is promoted Multi-grade teachers had to produce separate plans for all the grades in their class – they regarded this as an onerous task and said they would prefer to teach a mono-grade group of 50 pupils While this is a burden for teachers it can be seen as forcing them to differentiate between their pupils in a way that would also be useful for mono-grade teachers who generally do not pay enough attention to individual needs Assessment likewise is more of a bureaucratic burden for multi-grade teachers who have to produce tests for several levels Again this was seen to have positive benefits for the learners as more attention was paid to individual needs Classroom groupings in mono-grade classes begin with general whole-class instruction followed by individual seatwork – no sign of pair or small group work The writer’s conclusions from the study were: Peer instruction more likely to take place in multi-grade classrooms and this is felt to have benefits for learning (Amazon, Peru) Ames observed three strategies: teaching the class in two separate groups teaching the class as if it were one group with no differentiation of level (less common) teaching the class as a whole group and then separating them into two groups In the lessons observed, the teacher devoted very different amounts of time to each level. These teachers observed primary grades but above levels 1 and 2 i.e. already had basic reading and writing skills used the second strategy i.e. mainly teaching the class as if it were one level. (Amazon Peru) The third strategy (whole class followed by division into groups) – also primary grades but above levels 1 and 2 i.e. already had basic reading and writing skills - was used particularly by the two teachers who were more concerned than the others about the development of thinking and learning skills in their pupils. They were anxious for the pupils to be engaged in meaningful activities appropriate to their level of development. However, their division of pupils into groups was based totally on grade divisions and did not differentiate pupils within grades at all – though this can be educationally useful (groups can usefully be formed on the basis of mixed ability, same ability or social factors as well as on a grade basis). (Nepal) Often multi-grade teachers have classes in different rooms so children in one group are without a teacher while teacher is with other group (sometimes there is a kind of pupil monitor in charge of the teacherless group Teacher training programme in Nepal has the following four objectives: to prepare or plan educational activities required for multi-grade teaching to prepare self-learning activity (SLA) required for multi-grade teaching to manage classes in a way conducive to multi-grade teaching to teach students in two or more classes simultaneously Teachers are encouraged to divide multi-grade classes into T group and AM group(s). T = group which the teacher is with and AM = additional class(es). With AM classes teacher should provide self learning activities and should assign a Monitor to supervise in the teacher’s absence. A lot of attention is paid to developing SLA but the distinction between this and homework is not defined. Teacher is expected to provide monitor with clear instructions and any necessary answer sheets for the SLA (NB teacher in different room). When observing classes in Nepal Suzuki observed 5 different patterns: 1 teachers divide time during the day between each of the grades they have to teach and deal with each grade individually 2 teachers divide lesson period into two equal time sections and teach each group individually without providing SLA for other group 3 one grade is treated as main group and is taught and other group is given SLA and possibly assigned a monitor – teacher often returns to this second group at the end of the lesson to check them 4 teachers visit each grade frequently during lesson assigning SLA to both groups as they leave them 5 teachers put the grades together and teach them as one class (used especially in subjects where teaching not organised by grade such as sport, art, music) (Malawi) Croft observed how teachers used songs rather than punishment as a means of group control. (Malawi) Sometimes classes where combined. Main teacher taught lesson and one, occasionally two, other teachers (usually student teachers) circulated giving help to less able students. Pupils are also given extra help after the lesson (this can help to make up for lessons that pupils have missed – poor attendance a big problem for Malawian teachers) (Ghana) Classroom management not a focus of the study of the Schools for Life by Kwame Ak. but some points noted – some teachers attempted to pitch questions according to different ages within class some groupwork used when pupils of similar ages and abilities worked together in general not all that much attention was paid to the instructional needs of different ages within a class teachers did not seem to be inhibited or bothered by age range within class what is achieved in nine months is very impressive Facts about extent of multi-grade teaching (Little, introductory chapter) Australia, 1988, 40% pupils in Northern Territories in multi-grade classes Burkino Faso, 2000, 36% schools, 20% classes, 18% pupils multigraded England 2000 25.4% of all classes in primary ed were /mixed-year’ i.e. tow or more curriculum grades taught by one teacher France 2000 34% of public schools had combined classes (4.5% of these one teacher schools) India 1996 84% of primary schools had 3 teachers or fewer Ireland 2001-2 42% of all primary school classes consist of two or more grades Laos 24.3% of all primary school classes multi-graded Mauritania 2002-3, 30% of all pupils in multi-grade classes, 82% of these in rural areas New Brunswick Canada, 13/4% of classes in elem schools combined grades N. Ireland, 2002-3, 21.6% of all classes ‘composite’ Norway, 2000, 35% of all primary schools used multi-grade teaching Peru 1998 78% of all primary schools multi-grade Angela Little estimates that there are about 244 million children worldwide whose experience of primary education is likely to be multi-grade. These children are in developing and developed countries and in countries in transition. Intro chapter also provides a historical view pointing out that links between age and curriculum only developed in 19th century. In what kind of situations do multi-grade classes persist in 20th/21st centuries? schools in areas of low population density schools in area where population (students and/or teachers) is declining and mono-grade school no longer possible schools spread across a number of locations where some classes are multi-grade and some mono-grade with different teachers specialising in each type of organisation schools in areas of population growth where school system is expanding and enrolments in upper grades remain small and teachers few schools in areas where parents send children to more popular schools leaving low enrolments in less pop schools schools where numbers admitted exceed official class size meaning that additional classes have to be created schools which are generally mono-grade but fluctuating admissions necessitate occasional multi-grade organisation mobile schools in which one or more teachers move with nomadic or pastoralist communities schools in which teacher absenteeism is high schools in which official no of teachers employed could support mono-grade teaching but where for various reasons fewer teachers are actually employed schools in which pupils are organised into multi-grade groups for pedagogic reasons – often as part of a more general curriculum and educational reform (Turks and Caicos) Practice shows that this potential for innovative instruction in multi-grade classes is rarely used in practice with most teachers simply dealing with classes as if they were separate mini mono-grade classes. Most of current research comes from developed countries (USA, Australia, Holland, England). (Turks and Caicos) administrators in the Turks and Caicos see multi-grade classes as a temporary aberration, and yet mono-grade classrooms could learn a lot from them (Amazon, Peru) 73% of the total number of public primary schools are multi-grade. (Amazon, Peru) These 3 types of strategy (whole class, two groups, combination of the two modes) have been observed and recommended in other multi-grade situations and it is interesting that the Peruvian teachers developed them without having had any training in this. The writer pinpoints the Peruvian teachers’ interpretation of literacy as simply learning a set of coding and decoding skills as being a restricting factor in the way their classes were organised. The particular society in which they were operating showed a lot of learning going on outside the classroom in which young children were learning from older children in their own families or communities and relationships between different ages were generally very positive. (Berry and Little, London) Bennett et al (1983) found 213 different types of multi-grade organisational patterns in UK and argue against over-generalisation – huge contrasts, particularly, between urban and rural contexts (Mixed age classes in primary schools: a survey of practice, BERJ 9 (1) 41-56). This study found that: age and ability most usual reasons for assigning to multi-grade classes teachers of grades 3-6 more opposed to idea than 1-2 in grades 1-2 intra-class groupings more likely to be done on basis of ability than age heads of schools regardless of the types of classes in their schools agreed that multi-grade teaching places more of a burden (of preparation etc) on the teacher and requires more resources heads of schools saw advantages of multi-grade teaching in terms of flexibility of staff,, children and space heads of schools with multi-grade classes believed all the children got sufficient teacher attention, that older pupils did not resent younger pupils and that such classes provide greater stability and security for pupils Main challenges associated with multi-grade teaching (according to the London teachers Berry and Little surveyed and interviewed): meeting the needs of the National Curriculum – which approaches teaching and assessment on a year-group basis coping with different ability ranges within different age groups – so in one multi-grade class you might need to be dealing with about eight different groups in terms of the sort of work they need assessment – need to be preparing one age group for SATs (this was particularly reported on as a problem by teachers of Year1+2 classes rather than teachers of older groups) Most teachers expressed a preference for mono-grade classes – but not all and some said it was immaterial, key thing is that classes should be responsive. Most felt teaching approach was basically the same – just that you might have to cope with a bit more differentiation in a multi-grade group. There are also issues in ensuring there is no bullying, that older children do not feel they are doing work that is really for younger children, that all groups are stimulated, that all emotional needs are met. In terms of planning, most – but not all – the multi-grade teachers commented on the added difficulties of planning. They talked about the needs of planning up and planning down. When dividing multi-grade classes into groups most teachers said they did it by ability rather than age – though requirements of SATs interfered with this a bit. Another strategy that multi-grade teachers reported using was that of pairwork. They paired so that a higher ability pupil could help a lower ability one (regardless of age). One commented that a lower ability older pupil could have his confidence built up by being asked to help a younger child. Another said it was less embarrassing for a lower ability child in the younger group to be a tutee when his tutor was older. (Nepal) c. 60% of schools required multi-grade teaching (Malawi) Ministry of Education in Malawi in 2000 published as an objective the desire to reduce the average age range in a class from 10+ years to 5 years! Multi-grade teaching in Malawi is most common in lower-primary grades. The huge age range which is often found in sub-Saharan African classes is partly because of a policy of education for all which has opened up education for children who have not had it before thus meaning that older children had to go into starting grades. Although the population of Malawi is such that there are usually enough pupils in a year group to make a feasible mono-grade class, classes are often multi-grade because of difficulties with posting teachers to rural schools, lack of cover for teacher absence, lack of classrooms in rainy season. Socio-economic status is significant in how students progress through primary school – the age at which pupils start school, the regularity of their attendance, whether pupils are hungry, have warm clothes in winter, have pencils and paper all these socio-economic factors have a huge effect on their learning. Malawian lower primary guides for teachers give the pace, content and methods for teaching and learning for every lesson allowing for little variation pupils of different backgrounds or abilities. (Sri Lanka) Multi-grade teaching is not an official option. The only teacher resource for it is one single module produced by the National Institute of Education for its distance ed programme. Yet there are plenty of reports of multi-grade classes existing in practice in an estimated 18% of schools. And their number seems to be growing as the number of small schools is increasing. Reasons for multi-grade classes in Sri Lanka: low rural enrolments shortages of teachers loss of popularity of specific school leading to downgrading in its teacher entitlement schools in growing communities deciding to expand grade range on offer without having additional teacher entitlement teacher absenteeism Teachers in such contexts did not recognise themselves as multi-grade teachers. (Vietnam) Multi-grade schools are a small proportion of the schools in the country at c. 2.5% of primary classes but they are particularly common in rural communities. Problems of these schools isolated few teachers teachers don’t have much access to training limited teaching and learning resources often ethnic minority students particularly affected – and teachers usually Vietnamese so may be language problems (Sudan) Mobile multi-grade schools are an attempt to provide education for children in nomadic communities. These schools offer 4 years of basic schooling. The teacher lives and moves with the community. Teachers are recruited locally are given a 3-month training must have completed secondary ed receive incentives from the community as government salary is inadequate often deal with health of people and animals in the community too are usually the most educated people in the community (Ghana) Ghana has a large number of children who are ‘out of school’ and a multi-grade provision of basic skills is used to help them. Acute teacher shortages in poorer areas makes a full education infrastructure impossible. The target date for full universal primary education has been moved forward to 2015. This multi-grade provision is called Schools for Life and its aim is to help poor and deprived children living in remote and scattered areas mainly in the north of the country. Features of Schools for Life programme Classes in afternoon (so can help parents in morning) Targets 8-15 year olds though older and younger pupils not unknown After 9-month programme children expected to join mainstream schooling – though children are expected to reach different levels depending on their ability and their effort Programme covers literacy, numeracy and writing Max class size 25 – meant to be approx equal nos of girls and boys (though this parity has been difficult to achieve) In some areas it has been possible to have two or three classes running in parallel each with its own teacher Good teacher pupil ratio has led to good achievement Programme is multi-grade in that class will be highly diverse in terms of age and therefore different age groups in class require different instructional attention even if they are all working on the same basic content Evaluative comments Successful multi-grade classes are characterised by effective peer instruction and self-directed learning (CB) In multi-grade classrooms more evidence of a greater variety of independent work (e.g. pupils going to fetch dictionaries when they needed them) – probably because the teacher was not as available to them (Turks and Caicos) Much more interdependent work in multi-grade classes – as far as observer could tell the contact between pupils in such classes was on task (Turks and Caicos) Despite a reduction in direct instruction pupils in multi-grade classes did not necessarily suffer – partly perhaps because of the input they were receiving passively from the instruction of other levels (Turks and Caicos) Learning-to-learn skills more likely to be developed in multi-grade classes – especially where self-access materials available in the classroom (Turks and Caicos) When teacher was not with the level, the pupils were not particularly engaged in useful activities – pupils spent a lot of time just waiting to get the teacher’s attention. (Amazon, Peru) (Amazon, Peru) The strategy of teaching multi-grade pupils as one group was felt to have advantages in that: all children had the teacher’s attention for almost all the time the preparation burden on the teacher was less pupils could learn from each other – and seemed to do so particularly when the seating arrangements were not determined by level can improve relationships between the children who benefit from exchange of opinions, ideas and skills Yet disadvantages when this strategy is used all the time: approach tends to be very teacher-centred (though two of the teachers observed did use group work a little more than the others) differences of level either across grade or within grade are not addressed – this can be particularly hard on lower achievers or younger children higher ability or older children can get bored Type 1 (separate groups taught individually) – not particularly useful for the grade 1 pupils who had little teacher attention and were set mechanical and rather meaningless tasks to do on their own. Type 2 (whole class strategy) seemed to work better in that it presented a more social and communicative view of literacy. Type 3 (combination strategy) was relatively little exploited in this Peruvian context but would seem to hold promise. (London) Studies have been done into UK multi-grade teaching in rural environment (usually reports of such schools are positive, family atmosphere etc) and in urban environment in which some but not all classes are multi-grade (latter generally suggest that mono-grade teaching is better for pupils). Refs provided for examples of such studies. ???reference is important please note it. FO Response re rural schools see e.g. Cornall 1986, Galton and Patrick Curriculum and Practice in the Small Primary School, London, 1990, Francis 1992, Vulliamy and Webb 1995, Hargreaves et al 1996, Hayes, 1999, OFSTED Small Schools – How well are they doing? 2000 (available online at OFSTED site, accessed 2004), Ireson and Hallam Ability Grouping in Education, London, 200; re urban schools see particularly HMI Survey Primary Schools in England, London, 1978 – have just noted full details of some of rural refs, the rest if required can be found in Berry and Little’s bibliography (pp 85-86) (London) Main opportunities associated with multi-grade teaching (according to the teachers in their study): cognitive stretching – younger or less able pupils pulled along by being exposed to higher level work peer tutoring – felt to benefit both the peer who is mentoring and the one who is being taught behaviour modelling – younger children learn appropriate classroom behaviour from older ones (Nepal) Most of the teachers who were given some training in dealing with multi-grade classes took on board the practices promoted (such as developing self learning activity for the groups not directly being taught and making use of monitors). (Malawi) In developing countries multi-grade teaching is generally seen as second-best and only used when mono-grade teaching is not feasible. (Sri Lanka) Difficulties teachers commented on were: bridging the gap between the widely accepted mono-grade instruction and needs of multigrade classes addressing the different ability levels of students in different grade groups simultaneously addressing multi-grade situations without support or feedback fulfilment of multiple roles such as being a teaching principal and surrogate parent as well as coping with demands of multi-grade context meeting professional development needs given lack of awareness of available opportunities due to isolation (Vietnam) Health education was found to be an area where teachers in multi-grade classes could successfully: do a whole group presentation follow it with groupwork involving students in different activities set aims appropriate to the different grades within any one class (Sudan) Inferior status of multi-grade schooling is probably because of its association with the poorest and least well-resourced educational settings. Rigid curriculum not modified in any way to suit the needs of the mobile community. Teacher that Aikman and el Haj observed is effectively teaching four mono-grade classes at the same time. These mobile schools face major financial problems – pressure on parents more or less to finance and organise the school as is lack of state commitment to funding and supporting them. (Ghana) The success of the Schools for Life provision is impressive but it is often ‘wasted’ in that its graduates do not transfer to the public school system as was the intention (often because it is too far to a school). This provision is costly but it does achieve in nine months what schools take much longer to do. There are questions as to the sustainability of this provision. General conclusions about the system: multi-grade education can be a good alternative provision especially in circumstances where there is high repetition or drop-out, where there are children who not otherwise go to school, where there is socio-economic deprivation effective instructional organisation affects what is achieved multi-grade classes can contribute significantly to the provision of quality basic education Recommendations (Turks and Caicos) Pupils in both types of classes in the TCI could benefit from a different type of curriculum – one that would allow more for the diversity of cognitive development (the current curriculum is graded with related graded course materials) Teachers in both types of classes would benefit from training and support in how to innovate in their instructional approaches (e.g. in making structured use of group work or pair work) (Amazon, Peru) Dividing multi-grade class into ability groups for literacy teaching in grades 1 and 2 would not be so essential if the teacher had a different approach to literacy, seeing it more as a communicative and social practice. Situation would have been much better if the teacher: had planned her work better had made positive use of self-learning activities had made use of pupil monitors to help organise activities had encouraged group tasks (Amazon, Peru) The approach the writer recommends = a flexible one in which the teacher does not rely on one dominant approach (as the teachers she observed in Peru did) but is more varied. It allows for both individual and group work, both of which can be appropriate for different types of activity and encourages pupils to work at their own pace even within mono-grade groups. (Amazon, Peru) The positive relationships between different age groups in the community could be exploited in a positive way in the classroom. Ames particularly quotes I. Collingwood (1991) Multi-class teaching in primary schools: a handbook for teachers in the Pacific (UNESCO) as offering good training for multi-grade teachers (London) Since 1980s studies (e.g. by Hallam) have tended to focus on grouping practices. Hallam (2004) found that many schools had changed their grouping practices in response to govt guidelines in the National Literacy Strategy recommending more whole-class teaching (Grouping practices in the primary school: what influences change, BERJ 30(1) 115-140). Additional guidance given for multi-grade classes: reduce whole-class teaching time in favour of more group teaching increase group time and retain whole-class time by increasing total time use an additional adult to provide simultaneous teaching set by ability across a number of classes NB National Curriculum reinforces the year-group structure approach to teaching, despite the quarter of pupils in multi-grade classes. The amount of guidance given to teachers in such situations would not seem to be adequate. Recommendations made by teachers and heads in Berry and Little’s survey: taking multi-grade classes into account in the National Curriculum more QCA support for teachers in a multi-grade situation further professional development organised at school level – sharing of ideas etc more formal training in dealing with multi-grade classes – both pre-service and in-service (Nepal) Follow-up support and monitoring by educational supervisors is essential if knowledge and competence gained during training is to transfer into improved classroom performance and enhanced student achievement. (Malawi) (UNESCO 1994, Salamanca Statement Section 2) ‘Regular schools with this inclusive orientation are the most effective means of … achieving education for all; moreover, they provide an effective education to the majority of children and improve the efficiency … of the entire education system.’ (This was referring specifically to the inclusion of disabled children in the ordinary education system but Croft feels that the principle of diversity being a positive thing in the classroom for all pupils applies equally to the issue of multi-grade vs mono-grade classes). (Croft, 122) ‘Much of the pedagogy suggested in teacher education programmes for teachers working to implement EFA (Education for All) in developing countries has its roots in progressive Western primary practice which addresses diversity by striving to treat pupils as individuals. In large classes the guidance a teacher can give individually is stretched thinly, and teachers compensate for this by providing extra help after class. Some teaching strategies respond to the needs of various sub-groups of pupils within the class. With limited teaching and learning materials, a teacher-intensive rather than a resource-intensive pedagogy tends to develop. The ‘graded’ nature of the curriculum does, however, limit teaching addressed at pupils’ diverse needs. To implement EFA it will be necessary to enlarge the rationale for schooling and perhaps to challenge the ‘gradedness’ of schooling.’ Croft stresses the importance of teacher education in doing this. (Sri Lanka) Multi-grade teaching should be dealt with on teacher training courses. (Vietnam) Curriculum reform is needed to allow for topics to cross grades and be addressed in a way appropriate for the grade within a multi-grade class. self-study learning materials need to be developed teacher education with regard to classroom management, facilitating student-led activities and formative assessment is required (Sudan) There is a need for multi-modality provision which is flexible and adaptive and can cater for different sizes of school population and changing and fluid patterns of mobility and settlement (not a choice between mobile and boarding). A rethink is needed about how to provide education for nomadic children which incorporates good practice from around the world. A radical solution and a dramatic increase in resources are essential. (Ghana) SFL teachers have generally not gone through traditional teacher training and perhaps because of this do not see multi-grade classes as being a problem need to introduce discussion of multi-grade classes into teacher training programmes Red = questions to you (Turks and Caicos) In multi-grade classes there would be at least two groups working independently while the teacher gave instruction to another group – this was felt to benefit the students as they would be getting exposure to work at different grade levels, thus reinforcing and extending their learning opportunities simply by being in the same room where the teacher is presenting stuff to groups at different levels so even if they are supposed to be getting on with independent work, they may well be partially taking in what the teacher is doing with others. (Turks and Caicos) In comparison lower attainers in mono-grade groups would not have such exposure to material already covered and high-flyers would not have exposure to more stretching work. Mono-grade groups do not have the indirect exposure to the teacher presenting materials at other levels that multi-grade groups have (if all the multi-grade levels are being taught in the same room). (Berry and Little) 2000 DFES data say 25% of all pupils in primary ed in multi-grade classes. http://www.dfes.gov.uk/statistics/DB/SBU/b0222/030-t6.htm (2002) Evaluation Successful multi-grade classes are characterised by: effective peer instruction – the mentor pupils gain from teaching others as well as those who are taught self-directed learning taking place development of learning to learn skills pupils gaining from direct or indirect exposure to work at other levels young pupils learning appropriate classroom behaviour from older ones Less successful multi-grade classes characterised by: pupils not doing anything constructive while waiting for teacher's attention inadequate resources to cope with the needs of different groups Problems for the teacher planning burden is increased assessment is more complex Recommendations Training needed for teachers in how to deal with multi-grade classes Curriculum needs to take multi-grade needs into account (by e.g. dealing with topics in a cross-grade way) Community relationships can help support multi-grade work (as out-of-school learning often depends on older, more able teaching younger, less skilled) Materials appropriate for multi-grade activities need to be developed (self-study worksheets etc) Older pupils etc can be effectively used to monitor and support groups when teacher is occupied with others Positive aspects of multi-grade teaching should be emphasised (e.g. group work can aid learning) Multi-grade approach can usefully feed into mono-grade teacher training (as mono-grade classes also usually include range of ability) Multigrade teaching – reported patterns of work 1 Teacher teaches whole multi-grade class as if it were one mono-grade group.. PRESENTATION - whole group PRACTICE and PERFORMANCE A - small groups of same level doing work differentiated according to level B - small groups of mixed levels with older or more able spoils helping younger or weaker ones C - whole group, teacher possibly varying questions to suit the different levels of pupils D – individuals either at different paces or different exercises according to level 2 Teacher divides class into different mono-grade groups and teaches each group separately for part of the lesson but goes between groups frequently during the lesson.. A with first group as whole group followed by SAME with second group (while teacher is not with a group, they might be doing practice or production work relating to the topic of the lesson or of a previous lesson or even presentation work PRESENTATION through reading a textbook) PRACTICE and PERFORMANCE B - presentation with first group as whole group, sets them practice and performance - whole group work to do individually - presentation with second group as whole group, sets them individual practice and performance work Teacher then moves between groups checking on their practice and performance. 3 Teacher divides pupils into mono-grade groups and teaches each group for part of the day PRESENTATION PRACTICE and PERFORMANCE A - teacher with each group as if it were a mono-grade class -other groups effectively abandoned B – teacher with each group as if it were a mono-grade class, -other groups are assigned a monitor – reading a textbook, exercises set by teacher who may provide monitor with answer sheet 4 Teacher divides class into two groups according to level, teaches one group as the main class and the other as an additional group PRESENTATION PRACTICE and PERFORMANCE - teacher in main group - never teaches additional group which works individually on tasks set by the teacher References The above pages contain notes on chapters from Angela Little (ed), Education for All and Multi-grade Teaching: Challenges and Opportunities, Springer, 2006 Authors and titles of individual chapters referred to in the above notes are: Angela Little ‘Education for all: multi-grade realiti0es and histories’ Chris Berry ‘Learning Opportunities for All’ Patricia Ames ‘A multi-grade approach to literacy in the Amazon, Peru: school and community perspectives’ Chris Berry and Angela Little ‘Multi-grade teaching in London, England’ Takako Suzuki “Multi-grade teachers and their training in rural Nepal’ Alison Croft ‘Prepared for diversity? Teacher education for lower primary classes in Malawi’ Manjula Vithanapathirana ‘Adapting the primary mathematics curriculum to the multi-grade classroom in rural Sri Lanka’ T. Son Vu and Pat Pridmore ‘Improving the quality of health education in multi-grade schools in Vietnam’ Pat Pridmore with Vu Son 'Adapting the curriculum for teaching health in multi-grade classes in Vietnam' Sheila Aikman and Hana el Haj 'EFA for pastoralists in North Sudan: a mobile multi-grade model of schooling' Albert Kwame Akyeampong 'Extending basic education to out-of-school children in Northern Ghana: what can multi-grade schooloing teach us?' Keith Lewin 'Costs and finance of multi-grade strategies for learning: How do the books balance?' No notes taken from this chapter – didn't seem relevant Clemente Forero-Pineda et al. 'Escuela nueva's impact on the peaceful social interaction of children in Colombia' Angela Little 'Multi-grade lessons for EFA

![afl_mat[1]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005387843_1-8371eaaba182de7da429cb4369cd28fc-300x300.png)