Unit One - Dr.Antar Abdellah Home Page

Dr. Antar Abdellah

This chapter looks at an argument

: certain kinds of linguistic creativity traditionally associated with

(repetition, metaphor, rhyme and rhythm..etc) are a feature of ordinary, everyday conversation .

Rather than seeing literature as distinct from ordinary language, one can see the seeds of ‘literariness’ in much more mundane linguistic activity.

The chapter tries to answer the following questions:

What forms does everyday verbal art take?

How is it used in interaction with others?

Why should people spend time ‘playing’ with language in this way rather than getting on with more serious business?

language is being used for routine, and everyday purposes: to carry out the business of everyday interaction, conveying information from one person to another.

But in each case language also seems to draw attention to itself. Some formal aspect of language [such as sound, rhythm, grammar, meaning] is highlighted and this makes the utterance aesthetically amusing, [Crystal, 1998]

So some types of everyday language use may be seen as ‘ artful ’, or creative , But what makes them ‘artful ?

Consider the examples below:

1-A and B are sitting by some trees in a park:

A: (feeling bark) These are plane trees, aren’t they?

B: No, they’re quite patterned (wincing look) [ Joan

Swan, 2006 ]

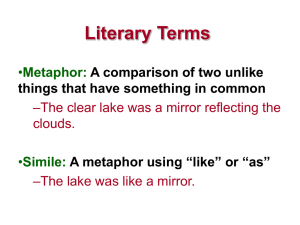

This is a pun, a form of word play which relies on ambiguity in word meaning. Puns often use

homophones, or near homophones, i.e. words with the same or similar sounds but different meanings, in this case

plane and plain.

Puns were famously defined by Samuel Johnson as ‘the lowest form of humor; they are also a feature of literature, and may be used for serious as well as humorous purposes.

2- A woman is talking about a man who works in her office:

And he knows Spanish, And he knows

French,

And he knows English,

And he knows German,

And he is a GENtleman

[ Deborah Tannen ,

1989, p.48]

This example involves repetition , which is a common feature of conversation. The speaker repeats a set of words, a grammatical structure and it includes also an intonation pattern that contributes to a sense of rhythm .

3-Darrel explains how his father persuaded him to study engineering at university, despite his uncertainty about his subject choice:

DARREL: he said ‘you might want to think about engineering as a major because you’re just pretty flexible when you get out, now I don’t think he was actually twisting my arm,

ELLEN : right.

DARREL: but I was — I was just like a leaf in the wind at that point, so I majored in engineering

(Adapted from Norrick, 2000/01, p. 251)

This example includes metaphor as a type of figurative or

metaphorical language: Darrel compares himself to a leaf in the

wind, a phrase that encapsulates his uncertainty and changeability. Metaphor is strongly associated with poetry and other forms of literature, but it also occurs frequently in everyday language.

4- A family is eating a meal outside, facing a building with a door high in the wall that leads to its loft, to allow access for storage. The door is divided into four sections. Someone remarks: ‘It’s a four-door store door .’ Instantly others begin to extend the phrase: ‘If there was a battle here it would be called the four-door store door war’; ‘If someone kept going on and on about the battle they’d be the four-door store door war bore ’ ... etc. The game runs sporadically through the meal

This example involves playing with rhyme, along with the formation of distinctly bizarre phrases and unlikely explanations of these. Unlike the other examples, it is a collaboratively produced game that runs across several speaking turns and involves all participants in the interaction. accompanied by despairing cries of ‘Oh no, not again!’ before it finally peters out. [ Joan Swan, 2006 ]

In general, certain forms of language, particularly those found in literature, are highly creative; but there isn’t a clear-cut distinction between ‘literary’ language and

more everyday forms.

Therefore, creativity is not restricted to literary texts but is a common aspect of our interactions with others.

According to Ronald Carter [ 1995b], examples of everyday spoken discourse display literary properties , and spoken discourse is associated with naturally occurring spoken data.

Ronald Carter identifies its different forms , such as ‘punning and playing’, ‘morphological

inventiveness’, ‘echoing and converging’; he also distinguishes between what he terms

‘pattern-reforming’ and pattern-reinforcing’ choices.

Pattern-reforming examples include puns, invented words or expressions: usages which, in various ways, play with and transform words and phrases.

Pattern-reforming choices involve a risk [ they may not work, they may be embarrassing. But speakers also stand to gain if they are successful] e.g. they may achieve an ‘enhanced regard’.

Pattern-reinforcing examples include repetition or echoing a previous utterance, i.e. without deviating from expected linguistic patterns.

Carter also argues that such forms of creativity serve particular interactional functions: they are often humorous; they serve in part to bring people together; they seem to be associated with informal, symmetrical social relations.

Deborah Tannen (1989) suggests that repetition comes from a basic human drive to imitate and repeat. Repetition may have certain interactional effects, e.g. bringing people together and signaling their mutual involvement, but in most cases it would not seem particularly creative.

Discussing the relationship between everyday linguistic creativity and literary language begs the question

of what literary

language actually is.

Carter (1999) distinguishes three models of literariness which underpin definitions

1-inherency model , 2- sociocultural model; and 3-cognitive model.

Inherency model

would see creativity or literariness as residing in certain formal properties of language: there is a ‘

focus on the message for its own sake

’. This property of language may also be termed

selfreferential

, where language is referring partly to itself and not simply to entities in the external world that are the object of discussion.

Sociocultural model sees literariness as socially and culturally determined.

Anthropological studies of literary performances in different cultural contexts also tend to take a sociocultural perspective on literariness. The concept is frequently extended to more everyday activity in recognition of the fact that there are parallels between ‘everyday’ and ‘literary’ performance.

this notion of performance can also describe what is often found in the most ordinary of encounters, when social actors exhibit a particular attention to and skills in the delivery of a message.

It also means to stress the fact that speaking itself always implies an exposure to the judgment, reaction and collaboration of an audience, which interprets, assesses, approves, sanctions, expands upon what is being said.

(Duranti, 1997, p. 16)

Cognitive model relates literary language to mental processes.

Deborah Tannen [1989] suggests that linguistic repetition derives from a basic human drive to repeat , and that is a kind of cognitive argument.

Furthermore, Guy Cook (1994, p. 4) argues that literary texts have an effect on the mind, helping us think in new ways and ‘refreshing and changing our mental representations of the world ’.

********************

Carter sees some value in both ‘ inherency ’ and ‘ sociocultural ’ models, but cognitive’ models are beneficial in that they help to explain the prevalence of creativity in everyday language. Carter’s main argument is that literariness is best seen as a cline [ continuum], or more accurately, a series of clines: whatever aspect of literariness is under consideration, it is appropriate to see texts as more, or less, literary rather than in terms of an opposition between literary and non-literary language. literariness is a matter of degree.

Guy Cook [ 1994] uses the term ‘ language play ’ for similar phenomena to those discussed by Carter under the heading of ‘creativity’. What benefits does Cook see in language play?

Basically, Guy Cook focuses on two aspects of play: playing with the structures of language, and invoking fictional worlds, He argues that linguistic play or fiction are manifested in a variety of different activities: children’s

rhymes and games, adults’ informal and private play

with language, but also more public activity, such as

adverts and other media language, and serious examples such as Martin Luther Kings speech. The mental adaptability associated with literary or artful activity is, according to Cook, beneficial to individuals but has also benefited humankind as a species.

[ Language Play, Language Learning (Cook, 2000)]

Rather than simply being a literary or poetic device, metaphor is an inherent property of language and the human mind, so that the ‘ fundamental roots of language are figurative ’ metaphor is a way of understanding the world, and they claim that language is a window on this process: the way we use language provides insights into how we perceive and think for instance, arguments are frequently seen in terms of war : they may be attacked or defended, won or

lost, a criticism may be right on target. Lakoff & Johnson [

1890] suggest that there is a conceptual metaphor or metaphorical way of thinking about argument

Arguments may also be seen in terms of buildings , as may theories : thus one can build , construct or demolish an argument/theory. A theory may have solid foundations, or it may need to be shored up, or buttressed (p. 46). Time is often seen in terms of money: it may be spent, used

profitably, or wasted; one may invest time in something, or have to budget one’s time (p. 8).

Lakoff and Johnson suggest, furthermore, that it is possible to establish links between different metaphorical systems : thus, up is generally positive and down negative in the case of conceptual metaphors such as:

HAPPY IS UP, SAD IS DOWN: ‘I’m feeling up’, ‘boosting one’s spirits’, that gives me a lift; ‘I’m down/low’, ‘my spirits sank’, etc.

Lynne Cameron [1999] discusses ‘the cognitive shift in metaphor studies’: how Metaphors do not need to involve novel connections, or even to be recognized as metaphorical by language users. The term is also extended to a wider range of figurative language, such as similes , allegories ,(characters or events represent or symbolize ideas and concepts)

Cameron distinguishes between deliberate’ and

‘conventionalised’ metaphor and identifies uses of both categories in educational and medical talk.

As for the relationship between ‘everyday’ and ‘literary’ metaphor,

Lakoff and Turner (1989) argue that poetic metaphor builds on and extends everyday metaphor, and also that our understanding of poetic metaphor depends upon its relationship to everyday metaphorical systems. They give the example of a poem by Emily

Dickinson, ‘Because I could not stop for death’.

Because I could not stop for Death

He kindly stopped for me

The Carriage held hut just Ourselves

and Immortality.

[ DEATH IS DEPARTURE ] that is used in English in phrases such as ‘he’s gone/passed away/no longer with us’, ‘dearly departed’, someone ‘slipping away’, or being ‘brought back from the dead’.

Cameron notes that the ‘cognitive shift’ in the study of metaphor has considerably extended what counts as metaphor. Her own study takes account of ‘conventionalized’ as well as

‘deliberate metaphor In discussing the limits of metaphor however she concedes that there is a danger of over-extending the notion of metaphor. It’s also important to note that metaphorical connections will differ in different cultural contexts.

One set of experiments relates to common idioms, often thought of as ‘ dead ’ metaphors.

Gibbs (1992) investigated peoples’ understanding of idioms such as crack the whip

(to be in control), spill the beans (reveal a secret and blow your stack (get very angry), assumed to be metaphorical in origin, but to have lost their metaphorical aspect over time. MIND IS A

CONTAINER, and ANGER IS A HEATED FLUID IN

A CONTAINER.

Basically, Conversational joking involves spontaneous humor within the give and take of conversation rather than telling a joke with a recognized format. Accordingly, Janet Holmes and Marra make a broad distinction between

‘reinforcing humour ’ which reinforces or maintains existing relationships; and ‘ subversive

humor’ which subverts or undermines existing relationships , and challenges power relationships.

Reinforcing humor : reinforcing solidarity (i.e. friendly, collegial) relationships

CONTEXT Project team members at the start of a meeting.

SANDY: we should start in the traditional way and have Neville tell us a story about his weekend.

[General laughter]

Neville obliges with an amusing anecdote, reinforcing and further developing collegiality and friendliness within this team.

Subversive humor : challenging power relations between individuals

CONTEXT Project team member [Sandy] (acting as chair of this meeting) calls his manager, Clara, to order.

SANDY: can we get back to business

CLARA: [laughs] sorry sorry.

[General laughter]

Sandy is here taking the opportunity to reprimand a superior. He criticizes Clara for digressing, a fault

Holmes and Marra identify humorous episodes not formally but functionally in terms of participants’ perceptions of humor; whether an episode seems designed to be humorous and how it is responded to. Holmes and Marra suggest that humor is used differently by different types of participants in meetings : it may be used by a person in authority to reinforce existing power relations or by someone in a subordinate position to challenge or subvert these.

Challenging institutional values

CONTEXT The team members discuss a proposal to record incoming telephone calls. Peg uses Troy’s question on the logistics of recording for a cynical retort.

TROY: how far do you get before you know it’s a personal call

PEG : [laughs] right at the end

[General laughter]

The organization has proposed recording incoming telephone calls in the section, purportedly in order to monitor the business aspects of these calls. These group members are sceptical about the organization’s

Conclusion

This chapter has explored various aspects of the argument that ‘artful’ language is pervasive and purposeful. It is therefore more appropriate to talk about a continuity between literature in its conventional sense and more everyday uses of language .In addressing these issues, the chapter has looked at different approaches to the study of creativity in spoken language.

Metaphor

Simile

Allegory

Pun

Repetition

Rhyme

Patterns of metaphor