Applied Time Series Analysis

advertisement

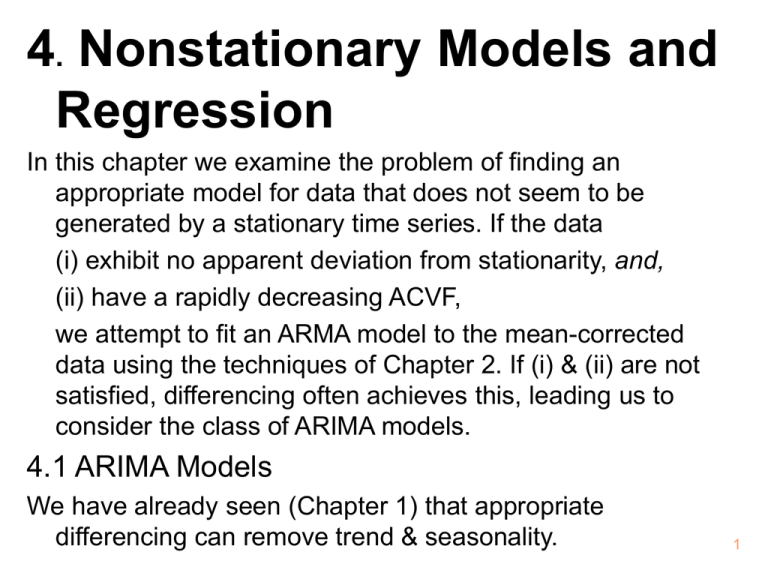

4. Nonstationary Models and

Regression

In this chapter we examine the problem of finding an

appropriate model for data that does not seem to be

generated by a stationary time series. If the data

(i) exhibit no apparent deviation from stationarity, and,

(ii) have a rapidly decreasing ACVF,

we attempt to fit an ARMA model to the mean-corrected

data using the techniques of Chapter 2. If (i) & (ii) are not

satisfied, differencing often achieves this, leading us to

consider the class of ARIMA models.

4.1 ARIMA Models

We have already seen (Chapter 1) that appropriate

differencing can remove trend & seasonality.

1

The AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA)

model, is a broadening of the class of ARMA models to

include differencing. A process {Xt} is said to be an

ARIMA(p,d,q) if {(1-B)d Xt } is a causal ARMA(p,q). We

write the model as:

f(B)(1-B)d Xt = q(B) Zt,

{Zt} WN(0,2),

The process is stationary if and only if d=0. Differencing Xt

d times, results in an ARMA(p,q) with f(B) and q(B) as AR &

MA polynomials.

Recall from Chapter 1 that differencing a polynomial of degree

d-1, d times, will reduce it to zero. We can therefore add an

arbitrary poly of degree d-1 to {Xt} without violating the

above difference equation. This means that ARIMA’s are

useful for representing data with trend. In fact, in many

situations it is appropriate to think of time series as being

made up of two components: a nonstationary trend, and a

zero-mean stationary component. Differencing such a

2

process will result in a stationary process.

Ex: ARIMA.TSM contains 200 obs from the ARIMA(1,1,0)

(1-0.8B)(1-B) Xt = Zt,

{Zt} WN(0,1).

Series

90.

80.

70.

60.

50.

40.

30.

20.

10.

0.

0

40

80

120

Sample A CF

1.00

160

Sample PA CF

1.00

.80

.80

.60

.60

.40

.40

.20

.20

.00

.00

-.20

-.20

-.40

-.40

-.60

-.60

-.80

-.80

-1.00

200

-1.00

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

3

The slowly decaying ACF of the series in previous example, is

characteristic of ARIMA’s. When searching for a model to fit

to such data therefore, we would proceed by applying the

operator (1-B) repeatedly, in the hope that for some d,

(1-B)d Xt will have a rapidly decaying ACF compatible with

that of an ARMA process. (Do not overdifference however,

as this can introduce dependence where none existed

before. Ex: Xt=Zt, is WN, but (1-B)Xt=Zt-Zt-1, an MA(1)!)

Ex: Apply (1-B)Xt to ARIMA.TSM, get ML model:

(1 - 0.787 B)(1-B) Xt = Zt, {Zt} WN(0,1.012).

Now fit min AICC AR model via ML to undifferenced data:

(1 - 0.802 B)(1 - 0.985 B) Xt = Zt, {Zt} WN(0,1.010).

Note the closeness in the coefficients between the two

models. The second model is just barely stationary, and it is

very difficult to distinguish between realizations of these

two. In general it is better to fit an ARIMA to nonstationary

4

looking data. The coefficients in the residual ARMA tend to

be further from 1. Their estimation is therefore more stable.

Forecasting ARIMA’s

The defining difference equations for an ARIMA(p,d,q) are not

sufficient to determine best linear predictors for Xt. If we

denote the residual ARMA model by Yt, that is,

(1-B)d Xt = Yt, for t=1,2,…

then, under the assumption that (Xt-d,…, X0) is

uncorrelated with Yt, t>0, the best linear predictor of Xn+h

based on the obs X1,…, Xn can be calculated recursively

similarly to the ARMA case, as:

Pn X n h = i =1 f P X n h-i j =h q n h-1, j X nh- j - Pn h- j -1 X n h- j .

pd

*

i n

q

As before, the {qj,i} are obtained via the Innovations

Algorithm, and the {fi*} are the coefficients in the

transformed AR polynomial, f*(z)=(1-z)d f(z). Similar results

hold for the MSE.

5

Summary of ARMA/ARIMA modeling procedures

1. Perform preliminary transformations (if necessary) to

stabilize variance over time. This can often be achieved

by the Box-Cox transformation:

fl(Xt) = (Xtl - 1/l, if Xt0, and l>0,

fl(Xt) = log (Xt,

if Xt>0, and l=0.

In practice, l=0 or l=0.5 are often adequate.

2. Detrend and deseasonalize the data (if necessary) to

make the stationarity assumption look reasonable. (Trend

and seasonality are also characterized by ACF’s that are

slowly decaying and nearly periodic, respectively). The

primary methods for achieving this are classical

decomposition, and differencing (Chapter 2).

3. If the data looks nonstationary without a well-defined

trend or seasonality, an alternative to the above option is

to difference successively (at lag 1). (This may also

need to be done after the above step anyway).

6

Examine sample ACF & PACF to get an idea of potential

p & q values. For an AR(p)/MA(q), the sample PACF/ACF

cuts off after lag p/q.

5. Obtain preliminary estimates of the coefficients for select

values of p & q. For q=0, use Burg; for p=0 use

Innovations; and for p0 & q0 use Hannan-Rissanen.

6. Starting from the preliminary estimates, obtain maximum

likelihood estimates of the coefficients for the promising

models found in step 5.

7. From the fitted ML models above, choose the one with

smallest AICC, taking into consideration also other

candidate models whose AICC is close to the minimum

(within about 2 units). The minimization of the AICC must

be done one model at a time, but this search can be

carried out systematically by examining all the pairs (p,q)

such that p+q=1, 2, … , in turn. (A quicker but rougher

method: run through ARMA(p,p)’s, as p=1,2,…, in turn.) 7

4.

8. Can bypass steps 4-7 by using the option Autofit. This

automatically searches for the minimum AICC ARMA(p,q)

model (based on ML estimates), for all values of p and q in

the user-specified range. Drawbacks:

a) can take a long time, and

b) initial estimates for all parameters are set at 0.001.

The resulting model should be checked via prelim. est.

followed by ML est. to guard against the possibility of being

trapped in a local maximum of the likelihood surface.

9. Inspection of the standard errors of the coefficients at the

ML estimation stage, may reveal that some of them are not

significant. If so, subset models can be fitted by

constraining these to be zero at a second iteration of ML

estimation. Use a cutoff of between 1 (more conservative,

use when few parameters in model) and 2 (less

conservative) standard errors when assessing significance.

8

10. Check the candidate models for goodness-of-fit by

examining their residuals. This involves inspecting their

ACF/PACF for departures from WN, and by carrying out

the formal WN hypothesis tests (Section 2.4).

Examples:

1) LAKE.TSM

Min AICC Burg AR model has p=2, min AICC IA MA model

has q=7, min AICC H-R ARMA(p,p) model has p=1.

Starting from these 3 models, we obtain ML estimates, and

find that the ARMA(1,1) model:

Xt - 0.74 Xt-1 = Zt 0.32 Zt-1, {Zt} WN(0,0.48),

has the smallest AICC.

9

2) WINE.TSM

Take logs and difference at lag 12.

Min AICC Burg AR model has p=12.

ML estimation leads to AR(12) with AICC=-158.9.

Coefficients of lags 2,3,4,6,7,9,10,11 are not sig.

Constrained ML leads to a subset AR(12) with AICC=172.5.

Min AICC IA MA model has q=13. After ML estimation,

coefficients of lags 4,6,11 are not sig. Constrained ML leads

to a subset MA(13) with AICC=-178.3.

Using Autofit with max p=15=max q, gives ARMA(1,12). Get

H-R estimates, follow up with constrained MLE by setting

coeffts of lags 1,3,4,6,7,9,11 to zero.

Resulting subset model has AICC=-184.1.

All 3 models pass WN tests. Choose last since it has

smallest AICC.

10

4.2 SARIMA Models

Often the dependence on the past tends to occur most

strongly at multiples of some underlying seasonal lag s.

E.g. monthly (quarterly) economic data usually show a

strong yearly component occurring at lags that are multiples

of s=12 (s=4). Seasonal ARIMA (SARIMA) models are

extensions of the ARIMA model to account for the seasonal

nonstationary behavior of some series.

The process {Xt} is a SARIMA(p,d,q)(P,D,Q)s with period s,

if the differenced series Yt=1-Bd1-BsDXt is a causal

ARMA process defined by:

f(B)F(Bs) Yt = q(B)Q(Bs) Zt, {Zt} WN(0,2),

where f(B) and F(B) are different AR polynomials of orders

p and P, respectively; and q(B) and Q(B) are different MA

polynomials of orders q and Q, respectively.

The idea here is to try to model the seasonal behavior via the

11

ARMA, F(Bs)Yt = Q(Bs)Zt, and the nonseasonal component

via the ARMA, f(B)Yt = q(B)Zt. These two are then

combined multiplicatively as in the definition. The

preliminary differencing on Xt to produce Yt, will take care of

any seasonal nonstationarity that may occur, e.g. when the

process is nearly periodic in the season.

SARIMA Modeling Guidelines:

With knowledge of s, select appropriate values of d and D

in order to make Yt=1-Bd1-BsDXt appear stationary. (D is

rarely more than 1.)

Choose P & Q so that ˆ (hs), h=1,2,…, is compatible with

the ACF of an ARMA(P,Q). (P & Q typically less than 3.)

Choose p & q so that ˆ 1,, ˆ s - 1 is compatible with

the ACF of an ARMA(p,q).

Choice from among the competing models should be based

on AICC and goodness of fit tests.

12

A more direct approach/alternative to modeling the differenced

series {Yt}, is to simply fit a subset ARMA to it without

making use of the SARIMA multiplicative structure.

The forecasting of SARIMA processes is completely

analogous to that of ARIMA’s.

Ex: (DEATHS.TSM)

Form Yt=1-B1-B12Xt to obtain a stationary-looking series

(s=12, d=D=1).

ˆ 12,

ˆ 24,

ˆ 36,, suggest an MA(1)

The values

(or AR(1)) for the between-year model i.e. P=0, Q=1.

Inspection of ˆ 1,, ˆ 11, suggests also an MA(1) (or

AR(1)) for the between-month model i.e. p=0, q=1.

Our (mean-corrected) proposed model for Yt is therefore

Yt = 1 q1B1 + Q1B12 Zt. Based on ˆ 1 andˆ 12, we

make the initial guesses: q1 =- 0.3, Q1=-0.3. This means

that our preliminary model is the MA(13):

13

Yt = 1 - 0.3B1 - 0.3B12 Zt = Zt - 0.3Zt-1 - 0.3Zt-12 0.09Zt-13.

Preliminary estimation algorithms don’t allow subset models.)

Now choose “constrain optimization” in the MLE window,

and select 1 in the “specify multiplicative relations” box.

Enter 1, 12, 13 to indicate that q1 q12 = q13.

Final model has AICC=855.5, and {Zt} WN(0,94251):

Yt = 28.83 Zt - 0.479Zt-1 - 0.591Zt-12 0.283Zt-13.

If we fit instead a subset MA(13) model without seeking a

multiplicative structure, we note that the coefficients of lags

2, 3, 8, 10, and 11 are not sig. Running constrained MLE,

we now find that the coefficients of lags 4, 5, and 7 are

promising candidates to set to zero. Re-running constrained

MLE, we finally find that the coefficient of lag 9 is not sig.

Constrained MLE once more gives model with AICC=855.6,

and {Zt} WN(0,71278):

Yt = 28.83 Zt - 0.596Zt-1 - 0.406Zt-6 - 0.686Zt-12 0.459Zt-13.

14

Predict next 6 obs.

4.3 Regression with ARMA Errors

In this section, we will consider a generalization of the

standard linear regression model, that allows for correlated

errors. The general model takes the form,

Yt = b1Xt1 bkXtk Wt, t=1,, n,

or, Y = X b W, where:

Y = Y1, ,Yn)T, is the vector of responses (or time series

observations).

X is the design matrix consisting of the n vectors of

explanatory variables (covariates), Xt = Xt1, ,Xtk)T.

b = b1, , bk)T, is the vector of regression parameters.

W = W1, ,Wn)T, is the error vector consisting of obs from

the zero-mean ARMA(p,q) model:

15

f(B) Wt = q(B) Zt, {Zt} WN(0,2).

(Note that in standard regression, {Wt} WN(0,2).)

We have already seen one application of this model for

estimating trend. For example, in a model with quadratic

trend, we would set Xt1=1, Xt2= t, and Xt3= t2, to give

Yt = b1 b2 t b3 t2 Wt.

In this example, each Xtj is a function of t only, but in the

general case they will be any covariates observed

contemporaneously with the response that are thought to

explain some of its variability. Examples might be

meteorological variables, chemical levels, socioeconomic

factors, etc.

Now, the Ordinary Least Squares Estimator (OLSE) of b is

{

bˆOLS = arg min Y - Xb T Y - Xb = X T X X T Y

-1

which coincides with the MLE if {Wt} IID N(0,2). (Take

any g-inverse in above; estimator unique if XTX )

nonsingular.)

16

The OLSE is also the Best (smallest variance) Linear

Unbiased E bˆ = b Estimator (BLUE) in the case of

uncorrelated errors (this is the Gauss-Markov Theorem). In

the case when {Wt} follows an ARMA(p,q), the OLSE is

linear and unbiased, but no longer the best estimator. The

BLUE of b in this case, is the Generalized Least Squares

Estimator (GLSE):

bˆGLS = argmin Y - Xb T Gn-1 Y - Xb

{

= X T Gn-1 X

-1

X T Gn-1Y

where Gn is the covariance matrix of W, i.e. Gn =E(WWT).

(For a given Gn, bˆGLS is also the MLE of b if W is Gaussian.)

If the ARMA parameters {f, q, 2 were known, it would

therefore be straightforward to obtain bˆGLS by maximizing

the Gaussian likelihood of the process

Wt = Yt - bTxt,

t=1, ,n.

17

In practice however, we don’t know {f, q, 2, so the entire set

of parameters, {b, f, q, 2 (as well as the order p & q), will

have to be simultaneously estimated from the data. We can

do this by minimizing the (reduced) likelihood L bˆ ,fˆ,qˆ

simultaneously for {b, f, q, (2 can be profiled out of the

likelihood equations, hence the name reduced likelihood),

to obtain bˆGLS fˆ,qˆ .

This suggests the following procedure for estimating the

parameters of a time series regression with ARMA errors:

Step 0

-1

0

T

ˆ

ˆ

(i) Set b = b OLS = X X X T Y

0

0 T

ˆ

X t , t = 1,, n.

(ii) Obtain the residuals Wt = Yt - b

(iii) Identify the order p & q of the ARMA model to fit to {Wt0},

0

ˆ

f

and obtain the MLE’s

and qˆ 0 .

18

Step 1

-1

1

0 ˆ 0

T

-1

T

-1

ˆ

ˆ

ˆ

b

=

b

f

,

q

=

X

G

X

X

G

(i) Set

GLS

n

n Y.

(ii) Obtain the residuals Wt 1 = Yt - bˆ 1T X t , t = 1,, n.

1

(iii) Obtain the MLE’s fˆ and qˆ 1 based on {Wt1}.

Step j, j2

-1

j

j -1 ˆ j -1

T -1

ˆ

ˆ

ˆ

,q

= X Gn X X T Gn-1Y .

(i) Set b = b GLS f

(ii) Obtain the residuals Wt j = Yt - bˆ j T X t , t = 1,, n.

(iii) Obtain the MLE’s fˆ j and qˆ j based on {Wtj}.

...

STOP when there’s no change in bˆ from the previous step.

(Usually 2 or 3 iterations suffice.)

Example: The lake data (LAKE.TSM)

Let us investigate if there’s evidence of a decline in the level

of lake Huron over the years 1875-1972.

19

We will fit the linear regression model Yt = b1 b2 t Wt.

Steps in ITSM2000:

Regression > Specify > Polynomial Regression >

Order=1.

GLS button > MLE button. Regression estimates

window gives the OLS estimates (std. errors), bˆ1 =10.202

(.2278), and bˆ2 =-0.024 (.0040), with the ML WN(0,1.251)

model for the residuals {Wt}.

Sample ACF/PACF button suggests an AR(2) model for

the residuals {Wt}. (The data now become estimates of

{Wt}. )

Preliminary estimation button > AR(2) > Burg, gives the

estimated Burg model for {Wt}.

MLE button gives the ML model for {Wt} and the updated

bˆ in the regression estimates window.

MLE button several times gives convergence to the final

model in regression estimates window:

Yt = 10.091 - 0.022 t 1.004Wt-1- 0.290Wt-2 Zt,

{Zt} WN(0,0.457).

20

A 95% CI for b2 is: -0.0221.960.0081=-0.038, -0.006; a

significant decrease in lake Huron levels. Note the change

in the std. errors of bˆ from OLS, highlighting the importance

of taking into account the correlation in the residuals.) Show

fit!

Example: Seat-belt data (SBL.TSM, SBLIN.TSM)

SBL.TSM contains the numbers of monthly serious injuries, Yt,

t=1,…,120, on UK roads for 10 years starting Jan ’75. In the

hope of reducing these numbers, seat-belt legislation was

introduced in Feb ’83 (t ≥ 99). To study if there was a

significant mean drop in injuries from that time onwards, we

fit the regression model:

Yt = b1 b2ft Wt, t=1,…,120.

where ft=0, 1 ≤ t ≤ 98, and ft=1, t ≥ 99 (file SBLIN.TSM).

Steps in ITSM2000:

Regression > Specify > Poly Regression, order 0 >

Include Auxiliary Variables Imported from File >

SBLIN.TSM.

21

GLS button > MLE button. Regression estimates

window gives the OLS estimates (std. errors), bˆ1 =1621.1

(22.64), and bˆ2 =-299.5 (51.71).

Graph of data (now the estimate of {Wt}) and ACF/PACF

plots, clearly suggests a strong seasonal component with

period 12. We therefore difference the original data at lag

12, and consider instead the model:

Xt = b2gt Nt, t=13,…,120.

where Xt= Yt-Yt-12 (file SBLD.TSM), gt=ft-ft-12 (file

SBLDIN.TSM), and Nt=Wt – Wt-12, is a stationary sequence

to be represented by a suitable ARMA process.

Open SBLD.TSM > Regression > Specify > Include

Auxiliary Variables Imported from File (no Poly

Regression, no Intercept) > SBLDIN.TSM.

GLS > MLE. Sample ACF/PACF button suggests an

AR(13) or MA(13) model for the residuals {Nt}. Autofit

option with max lag 13 for both AR & MA finds MA(12) to be

best.

22

Fitting MA(12) model via Preliminary estimation button >

MA(12) > Innovations, gives the estimated Innovations

Algorithm model for Nt.

MLE button gives the ML model for Nt and the updated

in the regression estimates window.

MLE button several times gives convergence to the final

model in the regression estimates window,

Xt = -325.2 gt Nt ,

with

Nt = Zt 0.213 Zt-1 - 0.633 Zt-12 , {Zt} WN(0,12,572).

Standard error of bˆ2 is 48.5, so -325.2 is very significantly

negative, indicating the effectiveness of the legislation.

Show fit!

23

5. Forecasting Techniques

So far we have focused on the construction of time series

models for both stationary and nonstationary data, and the

calculation of minimum MSE predictors based on these

models. In this chapter we discuss 3 forecasting techniques

that have less emphasis on the explicit construction of a

model for the data. These techniques have been found in

practice to be effective on a wide range of real data sets.

5.1 The ARAR Algorithm

This algorithm has two steps:

1) Memory Shortening.

Reduces the data to a series which can reasonably be

modeled as an ARMA process.

2) Fitting a Subset Autoregression.

Fits a subset AR model with lags {1,k1,k2,k3},

24

1<k1<k2<k3m (m can be either 13 or 26), to the memory

shortened data. The lags {k1,k2,k3} and corresponding

model parameters are estimated either by minimizing 2, or

maximizing the Gaussian likelihood.

Stationary

White

Data

Memory

Series

Noise

Shortening

SAR filter

{Yt}

{St}

{Zt}

Minimum MSE forecasts can then be computed based on

the fitted models.

Ex: (DEATHS.TSM). Forecasting > ARAR. Forecast next 6

months using m=13 (minimize WN variance). Info window

gives details.

25

5.2 The Holt-Winters (HW) Algorithm

This algorithm is primarily suited for series that have a locally

linear trend but no seasonality. The basic idea is to allow for

a time-varying trend by specifying the forecasts to have the

form:

PtYt h = aˆt bˆt h, h = 1,2,3,...

where,

aˆ t is the estimated level at time t, and

bˆt is the estimated slope at time t.

Like exponential smoothing, we now take the estimated level

at time t+1 to be a weighted average of the observed and

forecast values, i.e.

aˆt 1 = Yt 1 (1- )PtYt 1 = Yt 1 (1- )(aˆt bˆt ).

Similarly, the estimated slope at time t+1 is given by,

bˆt 1 = b (aˆt 1 - aˆt ) (1 - b )bˆt .

26

With the natural initial conditions,

bˆ2 = Y2 - Y1,

aˆ2 = Y2, and

and by choosing and b to minimize the sum of squares of

the one-step prediction errors,

n

t =3 (Yt - Pt-1Yt)2,

the recursions for aˆ t and bˆt can be solved for t=2,…,n.

The forecasts then have the form:

PnYnh = aˆn bˆn h, h = 1,2,3,....

Ex: DEATHS.TSM

Forecasting > Holt-Winters. Forecast next 6

months. Info window gives details.

27

5.3 The Seasonal Holt-Winters (SHW) Algorithm

It’s clear from the previous example that the HW Algorithm

does not handle series with seasonality very well. If we

know the period (d) of our series, HW can be modified to

take this into account. In this seasonal version of HW, the

forecast function is modified to:

PtYt h = aˆt bˆt h cˆt h , h = 1,2,3,...

ˆ t and bˆt are as before, and cˆt is the estimated

where a

seasonal component at time t.

With the same recursions for bˆt as in HW, we modify the

ˆ t according to,

recursion for a

aˆt 1 = (Yt 1 - cˆt 1-d ) (1 - )(aˆt bˆt ),

and add the additional recursion for cˆt ,

cˆt 1 = (Yt 1 - aˆt 1 ) (1 - )cˆt 1-d .

28

Analogous to HW, natural initial conditions hold to start off the

recursions, and the smoothing parameters {,b,, are once

again chosen to minimize the sum of squares of the onestep prediction errors. The forecasts then have the form:

PnYnh = aˆn bˆn h cˆnh , h = 1,2,3,...

Ex: (DEATHS.TSM). Forecasting > Seasonal Holt-Winters.

Forecast next 6 months. Info window gives details.

29

5.4 Choosing a Forecasting Algorithm

This is a difficult question! Real data does not follow any

model, so smallest MSE forecasts may not in fact have

smallest MSE.

Some general advice can however be given. First identify

what measure of forecast error is most appropriate for the

particular situation at hand. One can use mean squared

error, mean absolute error, one-step error, 12-step error,

etc. Assuming enough (historical) data is available, we can

then proceed as follows:

Omit the last k observations from the series, to obtain a

reduced data set called the training set.

Use a variety of algorithms and forecasting techniques to

predict the next k obs for the training set.

30

Now compare the predictions to the actual realized values

(the test set), using an appropriate criterion such as root

mean squared error (RMSE)

{

(Y

- PnYn h )

.

RMSE =

k h =1 n h

Use the forecasting technique/algorithm that gave the

smallest value of RMSE for the test set, and use it on the

original data set (training+test set) to obtain the desired outof-sample forecasts.

Multivariate methods can also be considered, (Chapters 5 and

6).

1

k

2

1/ 2

Ex: (DEATHS.TSM). The file DEATHSF.TSM contains the

original series plus the next 6 realized values Y73,…,Y78.

Using DEATHS.TSM, we obtain P72Y73,…,P72Y78 via each

of the following methods (and compute corresponding

RMSE’s):

31

Forecasting Method

HW

SARIMA model from 4.2

Subset MA(13) from 4.2

SHW

ARAR

RMSE

1143

583

501

401

253

(The 6 realized values of the series, Y73,…,Y78, are:

7798, 7406, 8363, 8460, 9217, 9316.)

The ARAR algorithm does substantially better than

the others for this data.

32

5.5 Forecast Monitoring

If the original model fitted to the series up to time n is to be used

for ongoing prediction as new data comes in, it may prove

useful to monitor the one-step forecast errors for evidence

that this model is no longer appropriate. That is, for

t=n+1,n+2,…, we monitor the series:

Zˆt = X t - Xˆ t = X t - Pt -1 X t

As long as the original model is still appropriate, the series {Zˆt }

should exhibit the characteristics of a WN sequence. Thus

one can monitor the sample ACF and PACF of this

developing series for signs of trouble, i.e. autocorrelation.

Example: Observations for t=1,…,100 were simulated from an

MA(1) model with q=0.9. Consider what happens in the

following two scenarios corresponding to the arrival of new

data for t=101,…,200, stemming from two different models.

33

Case 1: New data continues to follow the same MA(1) model

34

Case 2: New data switches to an AR(1) model with f=0.9

35

7. Nonlinear Models

The stationary models so far covered in this course are linear

In nature, that is they can be expressed as,

X t = j =0 j Z t - j , {Z t } ~ IID (0, 2 ),

usually with {Zt} Gaussian. (Xt is then a Gaussian linear

process). Such processes have a number of properties that

are often found to be violated by observed time series:

Time-irreversibility. In a Gaussian linear process,

(Xt,…,Xt+h) has the same distribution as (Xt+h,…,Xt), for any

h>0 (obs not necessarily equally spaced). Deviations from

the time-reversibility property in observed time series are

suggested by sample paths that rise to their maxima and fall

away at different rates.

36

Ex: SUNSPOTS.TSM.

Bursts of outlying values are frequently observed in

practical time series, and are seen also in the sample paths

of nonlinear models. They are rarely seen in the sample

paths of Gaussian linear processes.

Ex: E1032.TSM. Daily % returns of Dow Jones Industrial

Index from 7/1/97 to 4/9/99.

Changing volatility. Many observed time series,

particularly financial ones, exhibit periods during which they

are less predictable or more variable (volatile), depending

on their past history. This dependence of predictability on

past history cannot be modeled with a linear time series,

since the minimum h-step MSE is independent of the past.

The ARCH and GARCH nonlinear models we are about to

consider, do take into account the possibility that certain

past histories may permit more accurate forecasting than

others, and can identify the circumstances under which this

37

can be expected to occur.

7.1 Distinguishing Between WN and IID Series

To distinguish between linear and nonlinear processes, we will

need to be able to decide in particular when a WN sequence

is also IID. (This is only an issue for non-Gaussian

processes, since the two concepts coincide otherwise.)

Evidence for dependence in a WN sequence, can be obtained

by looking at the ACF of the absolute values and/or squares

of the process. For instance, if {Xt} ~ WN(0,σ2) with finite 4th

moment, we can look at, X 2 (h), the ACF of {Xt2} at lag h:

If X 2 (h) 0 for some nonzero lags h, we can conclude {Xt}

is not IID. (This is the basis of the McLeod and Li test of

section 1.9.)

If 2 (h) = 0 for all nonzero lags h, there is insufficient

X

evidence to conclude {Xt} is not IID. (An IID WN sequence

would have exactly this behavior.)

Similarly for | X | (h) = 0.

38

Ex: (CHAOS.TSM). Sample ACF/PACF suggests WN. ACF of

squares & abs values suggests dependence. Actually: Xn

=4Xn-1(1- Xn-1), a deterministic (albeit chaotic) sequence!

7.2 The ARCH(p) Process

If Pt denotes the price of a financial series at time t, the return

at time t, Zt, is the relative gain, defined variously as,

Pt - Pt -1

Zt =

,

Pt -1

Pt

or, Z t =

,

Pt -1

or the logs thereof. For modeling the changing volatility

frequently observed in such series, Engle (1982) introduced

the (now popular) AutoRegressive Conditional

Heteroscedastic process of order p, ARCH(p), as a

stationary solution, {Zt}, of the equations,

Zt = et ht ,

{et } ~ IID N(0,1),

39

with ht, the variance of Zt conditional on the past, given by,

ht = Var Z t Z s , s t = 0 i =1 i Z t2-i ,

p

and 0>0, and j≥0, j=1,…,p.

Remarks

Conditional variance, ht, sometimes denoted σt2.

If we square the first equation and subtract this equation

from it, we see that an ARCH(p) satisfies,

Z = 0 i =1 i Z t2-i vt ,

2

t

ht(et2-1),

p

4

E

(

Z

is a WN sequence. Thus, if

t ) ,

where vt=

the squared ARCH(p) process, {Zt2}, follows an AR(p).

This fact can be used for ARCH model identification, by

inspecting the sample PACF of {Zt2}.

40

It can be shown that {Zt}, has mean zero, constant variance,

and is uncorrelated. It is therefore WN, but is not IID, since

E Z Z t -1 ,...,Z t - p = 0 i =1 i Z

2

t

p

2

t -i

Ee

2

t

Z t -1 ,...,Z t - p = 0 i =1 i Z t2-i .

p

The marginal distribution of Zt is symmetric, nonGaussian, and leptokurtic (heavy-tailed).

The ARCH(p) is conditionally Gaussian though, in the

sense that Zt given Zt-1,..., Zt-p, is Gaussian with known

distribution,

Z t Z t -1 ,...,Z t - p ~ N 0, ht .

This enables us to easily write down the likelihood of

{Zp+1,..., Zn}, conditional on {Z1,..., Zp}, and hence compute

(conditional) ML estimates of the model parameters.

41

The conditional normality of {Zt} means that the best k-step

predictor of Zn+k given Zn,…,Z1, is Zˆn (k ) = 0, with

p

Var(Zˆ n (k)) = hˆn (k ) = 0 i hˆn (k - i),

i =1

where hˆn (k - i) = Zn2k -i , if k - i 0.

(This formula is to be used recursively starting with k=1.)

95% confidence bounds for the forecast are therefore

0 1.96 hˆn (k )

Note that using the ARCH model gives the same point

forecasts as if it had been modeled as IID noise. The

refinement occurs only for the variance of said forecasts.

For model checking, the residuals et = Zt / ht ~ IID N(0,1).

A weakness of the ARCH(p) is the fact that positive and

negative shocks Zt, have the same effect on the volatility ht

(ht is a function of past values of Zt2).

42

Ex: (ARCH.TSM)

Shows a realization of an ARCH(1) with 0=1 and 1=0.5, i.e.

Z t = et 1 0.5Z t2-1 , {et } ~ IID N(0,1).

Sample ACF/PACF suggests WN, but ACF of squares and

absolute values reveals dependence. In a residual analysis,

only the McLeod-Li test picks up the dependence. Simulate

by:

Specify Garch Model > Simulate Garch Process.

(Take care that ARMA model in ITSM is set to (0,0). If in

doubt, Info window always shows complete details.)

Ex: MonthlyLogReturnsIntel.TSM (STA6857 folder)

Xt is the monthly log returns for Intel Corp. from Jan 73 to Dec

97. A look at sample ACF/PACF of squares

(Squared….TSM) suggests ARCH(4) for the volatility ht.

43

> Specify Garch Model > Alpha Order 4 > Garch ML

Estimation. (Press button several times until

estimates stabilize.)

Estimates of 2, 3, 4 are not sig. (AICC = -397.0).

Refitting ARCH(1) gives fitted model:

X t - 0.0286= Z t = et ht , {et } ~ IID N(0,1),

ht = 0.0105 0.4387Z t2-1 , with AICC = -397.8.

Model residuals pass tests of randomness, but fail normality. Could try t

distribution for et.

> Plot Stochastic Volatility shows estimated ht.

Forecast volatility at t=301 via:

2

hˆ300 (1) = ˆ0 ˆ1Z300

= 0.0105 0.4387(-.0950- .0286)2 = .0172

Note: (i) average log return for period about 2.9%; (ii) 312<1 means

E(Zt4) finite; (iii) |1|<1 Zt ~ WN(0,.0105/(1-.4387)=0.0187).

44

7.3 The GARCH(p,q) Process

The Generalized ARCH(p) process of order q, GARCH(p,q),

was introduced by Bollerslev (1986). This model is identical

to ARCH(p), except that the conditional variance formula is

replaced by,

p

q

2

ht = 0 i =1 i Z t -i j =1 b j ht - j ,

with 0>0, j≥0, bj≥0, for j=1,2,….

Remarks

Similarly to the ARCH(p), we can show that,

Z = 0 i =1 ( i b i ) Z

2

t

m

2

t -i

vt - j =1 b j vt - j ,

q

where m=max(p,q), and vt= ht(et2-1), is a WN sequence.

Thus, if 1++p+b1++bq <1, the squared GARCH(p,q)

process, {Zt2}, follows an ARMA(m,q) with mean

E Zt2 = 0

.

m

1 - i =1 ( i b i )

45

Although GARCH models suffer from the same weaknesses

as ARCH models, they do a good job of capturing the

persistence of volatility or volatility clustering, typical in

stock returns, whereby small (large) values tend to be

followed by small (large) values.

It is usually found that using heavier-tailed distributions

(such as Student’s t) for the process {et}, provides a better

fit to financial data. (This applies equally to ARCH.) Thus

more generally, and with ht as above, we define a

GARCH(p,q) process, {Zt}, as a stationary solution of

Zt = et ht ,

{et } ~ IID(0,1),

with the distribution on {et} either normal or scaled t , >2.

(The scale factor is necessary to make {et} have unit

variance.)

Order selection, like the ARMA case, is difficult, but should

be based on AICC. Usually a GARCH(1,1) is used.

46

Apart from GARCH, several different extensions of the basic

ARCH model have been proposed, each designed to

accommodate a specific feature observed in practice:

Exponential GARCH (EGARCH). Allows for asymmetry in

the effect of the shocks. Positive and negative returns can

impact the volatility in different ways.

Integrated GARCH (IGARCH). Unit-root GARCH models

similar to ARIMA models. The key feature is the long

memory or persistence of shocks on the volatility.

A plethora of others: T-GARCH, GARCH-M, FI-GARCH; as

well as ARMA models driven by GARCH noise, and

regression models with GARCH errors. (Analysis of

Financial Time Series, R.S. Tsay, 2002, Wiley.)

47

Example: GARCH Modeling (E1032.TSM)

Series {Yt} is the percent daily returns of Dow Jones, 7/1/97 4/9/99. Clear periods of high (10/97, 8/98) and low volatility.

Sample ACF of squares and abs values suggest

dependence, in spite of lack of autocorrelation evident in

sample ACF/PACF. This suggests fitting a model of the form

Yt = a Zt ,

{Zt } ~ GARCH(p,q).

Let us fit a GARCH(1,1) to {Zt}. Steps in ITSM:

Specify (1,1) for model order by clicking red GAR button.

Can choose initial values for coefficients, or use defaults.

Make sure “use normal noise” is selected.

Red MLE button > subtract mean.

Red MLE button several more times until estimates

stabilize. Should repeat modeling with different initial

estimates of coefficients to increase chances of finding the

true MLEs.

48

Comparison of models of different orders for p & q, can be

made with the aid of AICC. A small search shows that the

GARCH(1,1) is indeed the minimum AICC GARCH model.

Final estimates: aˆ = .061, ˆ0 = .130, ˆ1 = .127, bˆ0 = .792,

with AICC=1469.0.

Red SV (stochastic volatility) button shows the

corresponding estimates of the conditional standard

deviations, σt=√ht, confirming the changing volatility of {Yt}.

Under the fitted model, the residuals (red RES button)

should be approx IID N(0,1). Examine ACF of squares and

abs values of residuals (5th red button) to check

independence (OK, confirmed by McLeod-Li test). Select

Garch > Garch residuals > QQ-Plot(normal)to

check normality (expect line through origin with slope 1).

Deviations from line are too large; try a heavier-tailed

distribution for {et}.

49

Repeat the modeling steps from scratch, but this time

checking “use t-distribution for noise” in every

dialog box where it appears.

Resulting min-AICC model is also GARCH(1,1), with same

mean, ˆ = 5.71, ˆ0 = .132, ˆ1 = .067, bˆ0 = .840, and

AICC=1437.9 (better than previous model).

Passes residual checks, the QQ-Plot (6th red button) is

closer to ideal line than before.

Note that even if fitting a model with t noise is what is initially

desired, one should first fit a model with Gaussian noise as

in this example. This will generally improve the fit.

Forecasting of volatility not yet implemented in ITSM.

50

Ex: ARMA models with GARCH noise (SUNSPOTS.TSM)

Searching for ML ARMA model with Autofit gives

ARMA(3,4). ACF/PACF of residuals is compatible with WN,

but ACF of squares and abs values indicates they are not

IID. We can fit a Gaussian GARCH(1,1) to the residuals as

follows:

Red GAR button > specify (1,1) for model order.

Red MLE button > subtract mean.

Red MLE button several more times until estimates

stabilize.

AICC for GARCH fit (805.1): use for comparing alternative

GARCH models for the ARMA residuals.

AICC adjusted for ARMA fit (821.7): use for comparing

alternative ARMA models for the original data (with or

without GARCH noise).

51