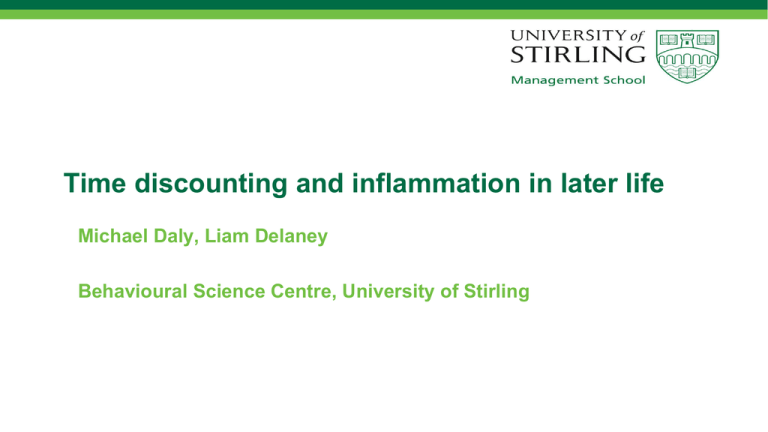

Time discounting and inflammation in later life

advertisement

Time discounting and inflammation in later life Michael Daly, Liam Delaney Behavioural Science Centre, University of Stirling Psychology literature • Established link between conscientiousness & subsequent physiological function and mortality (Friedman et al., 1993; Hampson et al., 2013) • Self-discipline facet of conscientiousness particularly predictive of later health (Costa et al., 2014) • Self-control and subsequent overweight, poor health, substance use, physiological functioning including metabolic abnormalities and inflammation gauged by CRP levels (Duckworth et al., 2010; Moffitt et al., 2011) Behavioural Economics literature • Time discounting has been linked to bmi (Borghans & Golsteyn, 2006; Chabris et al., 2008; Courtemanche et al., 2011; Dodd, 2008; Golsteyn et al., 2014; Ikeda et al., 2010; Takada et al., 2011; Weller et al., 2008) • Similarly, smokers discount the value of delayed money more than comparison groups (Bickel et al., 1999; Chabris et al., 2008; Fuchs, 1982; Goto et al., 2009) • Smoking example: Scharff & Viscusi (2011). Current smokers have an implied discount rate of 13.9%, as compared to 8.1% for non-smokers • Some evidence of links to other health behaviours such as physical activity and substance use (Adams, 2009; Chabris et al., 2008; Kirby et al., 1999) Is time discounting linked to health & biological functioning? • Proposed that those with higher discount rates invest less in their health (Grossman, 1972) • Evidence that early life discount rates predicts later health including early mortality (Chabris et al., 2008; Goldsteyn et al., 2014) • Opens the question as to the biological variables that mediate the association between time preferences and health outcome • Greater discounting of delayed rewards has been shown to correlate positively with health-related biological variables including systolic blood pressure and cortisol reactivity (Daly, Delaney, & Harmon, 2009; Lu et al., 2014) Why inflammation? • Inflammation is typically known as the body’s protective response to invasion and trauma such as pathogens or damaged cells resulting from infection, burns, injury • We are interested in low-grade chronic inflammation implicated in endothelial dysfunction, plaques/lesions, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease-related mortality (Benson et al., 2008; Libby et al., 2002) • Cardiovascular disease (e.g. stroke, angina, heart attack, congestive heart failure) is the leading cause of death worldwide (30% of deaths according to WHO) • Strongest biological predictors of cardiovascular disease across 61 meta-analyses are Creactive protein (top vs. bottom tertile) (RR: 2.43, 95% confidence interval (ci): 2.10–2.83) and fibrinogen (1 mg/L increase) (HR: 2.33, 95%ci: 1.91–2.84) (van Holten et al., 2013). Stronger evidence for a causal role of fibrinogen, CRP may capture inflammation generally Goal of the current study • 1) Examine whether time preferences predict inflammation levels • 2) Test whether a potential link between discounting and health is independent of a range of important potential confounding variables (e.g. income, wealth, cognitive ability, conscientiousness) • 3) Test how much of the discounting – inflammation link is explained by health behaviours • 4) Consider what other pathways might explain the relationship Methodology • Participants from ELSA (wave 5 in 2010-2011) completed questions relating to preference for monetary rewards over different time horizons • The current study utilizes data drawn from three waves of ELSA (wave 4, 2008-2009; wave 5, 2010-2011; wave 6, 2012-2013) • 1063 participants (50-75y, 55% female, 96.1% response rate) completed the preference elicitation module • 389 participants had complete biological data & time preference data Discounting Elicitation • Time discounting questions were presented on a laptop computer as part of series of financial decision-making games involving real rewards • The delay discounting game was called the ‘rectangle’ game and consisted of 12 binary choice options presented in adjacent rectangles • Instructions: (1) start the financial module with £10 (2) would win money from one of the 22 choices (3) randomly selected choice selected by the computer at the end of the section • Participants were instructed that the largest loss they could incur was £5 and max gain £70. They would receive winnings per post at the chosen time. Average expected payment median £35, mean £38. 13 mins median time taken (Alan et al., 2012) Discounting Questions Participants make a choice between a one-off payment of a smaller sooner amount in two weeks or a later larger in one month’s [or two month’s] time Choice 2 week payment (£) 1 month payment (£) 2 months payment (£) 1 25 26 2 25 28 3 25 30 4 25 32 5 25 35 6 25 38 7 25 26 8 25 30 9 25 35 10 25 37 11 25 40 12 25 45 Inclusion criteria: Discounting & inflammation data • • • • • • • • Descriptive Statistics Discount rate 2wks/1mth Discount rate 2wks/1mth C-reactive protein base C-reactive protein follow Fibrinogen baseline Fibrinogen follow-up • Valid N (listwise) N 953 983 641 639 664 657 389 Min. .02 .01 .20 .10 1.60 1.70 Max. .54 .33 9.90 9.80 5.40 5.30 Mean .15 .12 2.31 2.09 3.34 2.95 SD .20 .12 2.10 2.00 .55 .53 Discount rate • Use V = A/(1+ kD) • Where V is present value, A is the delayed or future value, k is the discount rate and D is the delay in weeks • Provides estimates of k within a range of values • Choice 1: £25 in 2 weeks and £35 in 4 weeks indicates a weekly k of 33% • Choice 2: £25 in 2 weeks and £38 in 4 weeks indicates a k of 54% • If the participant chooses the larger later option for 2 but not 1 this mean their discount rate k is somewhere between 33% and 54% per week. A rate of 43.5% is assigned Discount rate values • For participants • 2 weeks vs. 1 month = 15.59% (SD = 20.13) • 2 weeks vs. 2 months = 11.32% (SD = 11.91) • Discount rate values correlate highly (r (389) = .7, p <.001) • Combined rate, k = 13.45% (SD = 14.86%) • Those not included in the study k = 14.04% (SD = 15.01%), not significantly different (t (1023) = .6, p = .53) Discount rate values C-reactive protein (mg/L) & Fibrinogen (g/L) levels Covariates • Demographics: age, gender, race, marital status, retirement status, education level, log income, log benefit-unit non-pension wealth • Health: long-standing illness, arthritis, cardiovascular disease (stroke, congestive heart failure, angina, heart attack) • Health behaviour: smoking, physical activity (3 q’s frequency of mild, moderate, vigorous activity), drinking (3 q’s spirit, wine, beer measures/glasses/pints in last week), BMI (kg/m2) • Cognition: 10 words recalled without delay, with delay & verbal fluency (animal naming in 60 seconds) • Personality: 25 item Big Five • Missing data: 98.5% completion on average for covariates, largest missing for single variable was 5.4% & missing data replaced with mean Descriptives Discount rate and CRP Discount rate and fibrinogen Delay discounting and CRP 2 years later: adjusted for demographics & prior CRP levels Delay discounting and CRP 2 years later: adjusted for demographics, health/health behaviour & prior CRP levels Delay discounting and CRP 2 years later: adjusted for demographics, health/health behaviour, personality & cognition & prior CRP levels Delay discounting and fibrinogen 2 years later: adjusted for demographics & prior fibrinogen levels Delay discounting and fibrinogen 2 years later*: adjusted for demographics, health/health behaviour & prior fibrinogen levels * Decrease in coefficient attributable to a combination of smoking and BMI Delay discounting and fibrinogen 2 years later: adjusted for demographics, health/health behaviour, personality & cognition & prior fibrinogen levels Alternative explanations? • Ferguson (2013) discusses potential pathways that may apply including: - Treatment seeking - Communication with physicians - Treatment compliance - Stress and coping (e.g. Daly et al., 2014) - Health behaviour (objective PA, diet measurement, accurate adiposity) • Both discounting and biological functioning could be determined by genetic factors or early conditions • Discounting may shape trajectories of health over the lifespan (earlier mediators) Summary • Experimentally elicited discount rate predicts two measures of inflammation: C-reactive protein and fibrinogen • Associations are larger than population cross-sectional associations between socioeconomic status (e.g. wealth, education) • Associations are robust to adjustment for a broad set of demographic factors, income, wealth, personality, cognitive ability and prior inflammation levels • BMI and smoking account for 20% of the link between k & fibrinogen • Link between k & CRP is not explained by health, health behaviour, or confounding by personality or cognitive ability • Inflammation could be a key pathway between discounting and health outcomes including mortality