72x36 Poster Template - University of Central Florida

advertisement

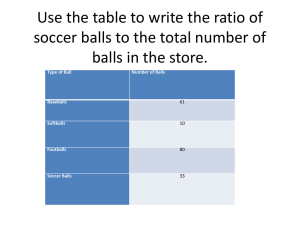

Kyle S. Beyer, Maren S. Fragala, Gabriel J. Pruna, Carleigh H. Boone, Jonathan D. Bohner, Jeremy R. Townsend, Adam R. Jajtner, Nadia S. Emerson, Jeffrey R. Stout, FACSM, Jay R. Hoffman, FACSM, Leonardo P. Oliveira Institute of Exercise Physiology and Wellness, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FLA, INTRODUCTION • Age-related cognitive decline is associated with an increased risk of developing dementia.1 • Decreased spatial awareness and reaction time lowers an individual’s ability to process information and react to situations.2 6 Weeks Resistance Training or Control Post-Testing • Peripheral Visuomotor Reaction • Visual and Motor Reaction • Spatial Awareness Participants • Twenty-five previously untrained older adults (70.64 ± 6.11 y; 1.69 ± 0.09 m; 80.72 ± 19.42 kg) volunteered for the study. • A total of thirteen men and twelve women were randomly assigned to either an experimental group (n=13) or control group (n=12). Table 1: Participant Characteristics • Spatial awareness was assessed by completing one core session on the Neurotracker, a 3dimensional multiple object tracking device.5 • All reaction times were assessed with the DynaVision D2 Visuomotor Training Device. Changes in Perceptual 3D Tracking Threshold 0.9 0.8 • Peripheral visuomotor reaction time was measured with one trial of the Mode A program. Control Training • During Mode A, a participant has sixty seconds to hit as many lights on the board as quickly as possible as they illuminate one at a time. • Visual, motor and physical reaction times were measured with ten trials of the Reaction Test. • During this test participants were instructed to track four of the eight yellow balls as they moved around the screen. Changes in Physical Reaction Time 0.6 0.975 0.95 Dynavision D2 Visuomotor Training Device • For the Reaction Test, participants pressed and held down a light directly in front of them. Another light would illuminate on the other side of the board. The participant would then release the original light and strike the newly lit light. Training Protocol 0.925 0.55 0.9 0.5 0.875 0.85 0.825 0.8 0.775 0.45 0.75 0.725 0.4 0.7 Pre Post Pre Post • Participants in the experimental group completed two resistance training sessions per week over the six week intervention period. Figures 1-3: Changes from pre-testing to post-testing for each group in variables that likely improved with resistance training. • Each training session lasted for one hour and there was at least fortyeight hours between sessions to allow for proper recovery. SUMMARY & CONCLUSIONS • Table 2 shows mean changes and differences between groups expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Probability of positive, trivial and negative effect and magnitude based inferences. Qualitative Inference % Negative % Trivial Variable Difference Between Groups ± 90% CI % Positive Mean and Percent Change Stages of the Neurotracker: a) Starting screen displaying 8 yellow balls. b) Four of the yellow balls light up white indicating that they are the ones to be followed. c) All balls return to yellow and move around the screen for 8 seconds. d) After the balls stop moving they are numbered 1-8. e) Participants select four of the balls that turn white as they are selected. Post Changes in Visual Reaction Time • Six weeks of resistance exercise training was shown to have beneficial effect on spatial awareness and visual and physical reaction times. • To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to examine how resistance exercise effects spatial awareness and the distinct visual and motor aspects of reaction time. • Previous research has shown resistance exercise to improve cognitive function at training periods of six to twelve months.3 This study indicated that a short-term resistance training period of only six weeks is sufficient to see results. • While only spatial awareness, visual and physical reaction times were likely to improve with resistance training, peripheral visuomotor and motor reaction times were trending towards improving but results were unclear because of high standard deviations. PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS Table 2: Mean and Percent Changes PURPOSE 0.5 Pre RESULTS • Currently it is unknown how resistance exercise training effects spatial awareness and subsets of visual and motor reaction time. 0.6 0.3 • Magnitude-based inferences provide a more useful statement about the clinical or practical application of the data than null hypothesis testing.6 A participant completing the Neurotracker test 0.7 0.4 • Magnitude-based inferences were generated at a 90% confidence interval, utilizing a p value and value of effect from a paired samples t-test.6 • Previous research has shown an improvement in various aspects of cognitive function Participant completing the leg extension with aerobic and resistance exercise with their personal trainer exercise.3,4 • Previous research has utilized psychological tests and MRI imaging to assess cognitive function. However, with new technologies, we will be able to test spatial awareness and specific aspects of reaction time. • To determine the effects of six weeks of resistance exercise training on the cognitive function and visuomotor reaction time of previously untrained older adults. Reaction Time • A dynamic warm-up and full body workout was completed at all training sessions. The workout consisted of seven or eight exercises targeting all major muscle groups. Statistical Analysis Spatial Awareness • The speed at which the balls moved was increased or decreased until an appropriate threshold was reached. RESULTS CONT. Reaction Time (s) Pre-Testing • Peripheral Visuomotor Reaction • Visual and Motor Reaction • Spatial Awareness METHODS CONT. Threshold Speed Cognitive function (CF) has been shown to decline as a person ages. Risks associated with this decline include an increased risk of falling or the development of dementia. Several studies have shown that aerobic exercise can slow this decline, and in some cases, improve CF in the older population. However, few studies exist that have investigated the effects of resistance training on CF. PURPOSE: To determine the effects of a 6-week resistance training program on CF in previously untrained older adults. METHODS: Twenty-five previously untrained older adults (70.64 ± 6.11 y; 1.69 ± 0.09 m; 80.72 ± 19.42 kg) volunteered for the study. Participants were split into two groups. The experimental group (n=13) underwent full-body resistance training two days a week for six weeks. The control group (n=12) continued on their normal physical activity routines. CF was evaluated before and after the training period with two visuomotor reaction tests where average peripheral, visual, motor and physical reaction times were recorded and a perceptual 3D object tracking test where a threshold was determined. Independent t-tests were used to make magnitude based inferences comparing changes in CF scores between training and control groups. RESULTS: Data suggests that resistance training is “likely beneficial” at improving perceptual 3D tracking threshold. Also, visual and physical reaction times were shown to “likely” improve with resistance training. It is “unclear” how training will affect peripheral visuomotor or motor reaction times. CONCLUSION: Older adults who undergo six weeks of resistance training may experience improvements in aspects of their CF. Resistance training may therefore be an effective means to slow age related cognitive decline. METHODS Reaction Time (s) ABSTRACT Training Group Control Group Neurotracker Threshold Speed 0.178 ± 0.163 40.0% 0.021 ± 0.246 2.9% 0.160 ± 0.150 85.0 14.3 0.8 Likely Beneficial Peripheral Visuomotor Reaction Time (s) -0.102 ± 0.072 9.0% -0.072 ± 0.110 6.3% 0.030 ± 0.066 38.5 57.7 3.8 Unclear Visual Reaction Time (s) -0.078 ± 0.182 14.6% -0.008 ± 0.048 1.7% 0.070 ± 0.093 Motor Reaction Time (s) -0.053 ± 0.084 14.8% -0.022 ± 0.101 5.6% 0.032 ± 0.065 • The results of this study support the use of resistance training to improve spatial awareness and reaction times in older adults. • Resistance exercise training may be an effective treatment option to prevent age-related cognitive decline or dementia in older adults. • Older adults could improve their physical and psychological wellbeing by engaging in resistance exercise training. REFERENCES 1. 76.3 19.8 3.9 61.8 28.9 9.4 Likely Beneficial Unclear 2. 3. 4. 5. Physical Reaction Time (s) -0.123 ± 0.188 14.0% -0.031 ± 0.112 3.6% 0.093 ± 0.110 80.2 17.2 2.6 Likely Beneficial 6. Riewald, S. (2009). Exercise for improved cognitive function in the elderly. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 31(5), 89-90. Salthouse, T. A. (1995). Selective influences of age and speed on associative memory. American Journal of Psychology, 108(3), 381-396. Liu-Ambrose, T., Nagamatsu, L. S., Voss, M., Kahn, K. M., & Handy, T. C. (2012). Resistance training and functional plasticity of the aging brain: A12-month randomized controlled trial. Neurobiology of Aging, 33, 1690-1698. Weuve, J., Kang, J. H., Manson, J. E., Breteler, M. M. B., Ware, J. H., & Grodstein, F. (2004). Physical activity, including walking, and cognitive function in older women. The Journal of the American Medical Association,292, 1454-1461. Faubert, J., & Sidebottom, L. (2012). Perceptual-Cognitive Training of Athletes.Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 6(1), 85. Hopkins, W. G. (2007). A spreadsheet for deriving a confidence interval, mechanistic inference and clinical inference from a P value. Sportscience, 11, 16-20.