With the flow - De Amsterdamse Go Club

advertisement

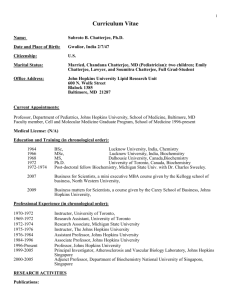

Go: With the Flow January 2002 Go: With the Flow Meyer and Silla Northeastern Remembers Letters Sports E Line Books Alumni Passages Classes From the Field First-Person Huskiana GO: WITH THE FLOW Ancient Buddhist monks and samurai warriors played it. Einstein was a devotee. In Asian business circles, it cements relationships, much the way golf does in America. But could this deceptively simple, endlessly fascinating 4,000year-old game really improve your management choices? And your life? Think Monopoly, with manners. It’s a territorial game that Einstein enjoyed and the Internet embraces, where an Attila the Hun approach won’t get you to Marvin Gardens, and closing the deal requires more than plundering and pillaging. To win at Go—also known as igo, wei ch’i, or baduk, depending on whether you’re playing in Japan, China, or Korea—you need patience, shrewdness, big-picture thinking, and, yes, even the capacity for sacrifice. Those who keep their power mongering in check earn large chunks of a gridded board—not to mention a new view of the world. Used to teach business strategy in both Asia and America, Go looks like a cinch at first. But be forewarned: There’s no $200 waiting for you as you sneak past jail. Go players have to earn their keep. In his living room, Sangit Chatterjee sits on his heels like a predator, muscles exuding energy. His hands rest on http://www.northeastern.edu/magazine/0201/go.html[7/13/2012 12:58:42 PM] Go: With the Flow the patterned throw rug beneath him as he stares at the game board. Only the ceiling fan moves. He could be a general in a war room, or Churchill, perhaps, following the progress of the Dunkirk flotilla, lives hanging in the balance. Across from Chatterjee, Yang Huiren sits cross-legged on the floor, a slightly raised knee the lone interruption of symmetry. Through a window open onto Beacon Street drifts an air conditioner’s distant moan. No birdsongs, no snippets of conversation, no car engines coming to life. Even the fan pays homage to the play as it rotates noiselessly overhead. The men move their eyes over the board. As games go, this one seems relatively unencumbering. There isn’t a great deal of equipment to haul around—no skates, no balls, no sticks. There’s no trump, no “shooting the moon.” No dice, no Community Chest cards. No possibility of winning by chance. All the pieces look the same, except for their color, like checkers. And beginners have to remember only four basic rules. What’s kept the game popular for roughly 4,000 years? Proficiency takes practice. A lot of practice. And getting good is synonymous with getting hooked. In this sense, Go is like Monopoly. Once you’ve acquired Boardwalk and Park Place, buying some hotels for your property becomes an obsession. Dinner can wait. This afternoon, Chatterjee is a sparring partner and a rapt pupil. Other times, he’s a semiprofessional tabletennis player. And in his professional capacity, he’s a management science professor at Northeastern’s College of Business Administration, where he’s worked since 1979, teaching classes in statistics, writing articles with titles like “The Evolution of Dominant Market Shares” or “A Pareto-Like Conjecture in Multiple Regression,” consulting for prominent businesses. The professor’s interest in Go goes far beyond the casual. In 1974, between jobs, Chatterjee—already ranked as a fairly strong beginner—went to Tokyo, drawn by a fascination with Japanese culture and with Go’s mathematical and experimental attributes, eager to strengthen his game. “For six months, I played all day and all night. I studied Japanese, made contact with professional players. Progress was slow—learning Go takes constant repetition,” Chatterjee says. After months of study at the Japanese government– funded Go Institute, Chatterjee was a 1-dan player, a rank that ordinarily takes three to four years of regular study and play to achieve. He is now a 5-dan player. Yang, Chatterjee’s opponent and teacher today, is more highly skilled, a professional. http://www.northeastern.edu/magazine/0201/go.html[7/13/2012 12:58:42 PM] Go: With the Flow Go boards look like a cross between graph paper and a checkerboard. Traditional Japanese boards, which can weigh 80 pounds or more, are placed on the floor between two players. (According to legend, samurai warriors used their swords to carve the straight lines on their boards.) Standard wooden tabletop versions measure 16 by 18 inches and weigh about 4 to 6 pounds. For computer geeks, a variety of websites offer virtual boards. Unlike checkers and chess, which are played within the spaces of their grids, Go is played on the lines, at the intersections. Official boards have a 19 by 19 grid, with 361 intersections. OMNI magazine once calculated that this allows for 10761 possible moves, compared with chess, with 64 squares and 10120 moves. Beginners usually start small, with a 9 by 9 grid, like an expanded tic-tac-toe. Once their territorial instincts are sufficiently whetted, though, new players advance on to larger boards. Chatterjee examines the thick wooden board as if he were following the path of an insect or the ebb and flow of a skirmish: Eyes stopping, backing up, then returning to a group of black and white stones on the lower righthand corner. Six black stones nestle within five white ones in a V formation. Chatterjee eyes the group at length, as if it were contemplating treason. Other white and black groups dot the board, like an imperfect mosaic. Yang stares fixedly from his side, neither his body nor his eyes conveying any information to his pupil. Outside, a distant siren wails. No one moves. To start a game, a player puts a game piece, called a stone, on any intersection on the board. The player with the black stones always plays first, followed by the player with the white stones, each in turn placing one stone on one intersection. To match a standard board’s 361 intersections, games generally come with 361 stones (181 black, 180 white), though there is no official limit on the number of stones that may be played. Once placed, stones don’t move unless they’re captured, allowing players to study every play leading up to the one at hand. In Monopoly, no one remembers how bombastic Uncle Harry, the self-appointed banker who sells his Get Out of Jail Free cards at extortionist prices, ended up with all the utilities. In Go, players can see exactly how territory got captured, because stones played earlier remain on the board as new ones are added. http://www.northeastern.edu/magazine/0201/go.html[7/13/2012 12:58:42 PM] Go: With the Flow Two minutes pass. Finally, Chatterjee picks up a stone, hesitates for a fraction of a second, then places it on the board with a soft click and a groan. Yang bolts upright, thrusting his upper body over the board toward Chatterjee. “Yes! That’s the only move!” he shouts, arms outstretched as if he could pick up the board and clasp it to his chest in appreciation. Go players are ranked according to their skill. Beginners hold the rank kyu. Someone just starting to play is usually ranked 40 kyu; someone who has played a few years may be ranked 1 kyu. The lower the kyu, the stronger the player. Dan is the rank given to advanced amateurs, who range from 1 to 7 dan—the higher the dan, the stronger the player. (A Go aphorism says, “You must play a thousand games to become 1 dan.”) And then there are the professionals, also ranked from 1 to 9 dan, though these are different, higher rankings than at the amateur level. Professionals and strong amateurs study opening moves, called fuseki, for years. But for beginners, strategy can be elusive. After a few games, however, even new players realize that grouping stones in a corner of the board leads to a frightful outcome. A more productive strategy is to line stones up some distance from a corner, providing escape routes, if necessary. Once a corner is secured, fortification and expansion can follow. Yang responds with his own clicking stone, which Chatterjee quickly answers. They alternate stones with a feverish precision, as if they’re completing a mosaic according to some prescribed time and manner. From above, the board looks like a small city in the midst of a boom. The game of Go is all about real estate. One object is to create territories by surrounding vacant areas of the board with your stones. The other is to capture your opponent’s stones by surrounding them on all four sides with your stones. Throughout play, stones are attacking, defending, escaping, surrounding. Evasion, deception, and intrigue run rampant. Strategy is paramount. And a player needs to be greedy: The one with more territory and more captured stones wins. http://www.northeastern.edu/magazine/0201/go.html[7/13/2012 12:58:42 PM] Go: With the Flow “Go is like six chessboards joined together, with all six games happening at the same time,” says Chatterjee. Because of the simultaneous activity on a field of action, the game has been considered analogous to war. In 1942, in fact, Life magazine used Go concepts to explain Japan’s war strategy in the Pacific theater. But Chatterjee believes the world of global marketing provides an equally accurate and relevant metaphor. Go strategy requires making concessions and sacrifices, forgoing short-term victory for long-term gain, knowing when to fight and when to avoid fighting. Ultimately, the winner is the one who makes better decisions—decisions based on what is happening all around the board, not just locally. For business professionals like Chatterjee, who has an MBA and a PhD in statistics from New York University, along with a BE from Calcutta University, Go is a powerful teacher. “It is a laboratory for strategic analysis,” Chatterjee says. “The Go board is the market, and two players are trying to occupy it.” For Northeastern’s high-tech MBA students, Go is part of the curriculum. Chatterjee teaches Go strategy in an allday weekend elective course. “The primary focus is how to translate Go into global markets,” says Fred Hoskins, the College of Business Administration’s executive director for external relations. “Go encourages a fluid, flexible way of thinking.” Go’s handicap system, where the weaker player gets extra stones to place on the board before play begins, levels the playing field, reducing the possibility that beginners will be annihilated the first time they sit across from cutthroat Uncle Harry. Eventually (usually in about an hour for beginners, two for advanced players), all the territory on the board is carved out, and the game ends—this is the intriguing part—by mutual agreement. Stones sit side by side, as if by truce, until the endgame accounting is completed. “Go is not a winner-take-all game. In a 40–42 game, even if you lose, you still have won some territory. Just like in the marketplace, there are multiple winners, although in absolute terms there is one who has made more profit,” Chatterjee says. “Go is more open to the notion that one does not have to wipe out someone else in order to be successful,” says Thomas Pucciarello, director of management development at BAE Systems, a defense contractor in southern New Hampshire, where Chatterjee is teaching the company’s managers to play Go. “We can achieve what we want without devastating someone else. To http://www.northeastern.edu/magazine/0201/go.html[7/13/2012 12:58:42 PM] Go: With the Flow claim the majority of the board doesn’t mean we own the road.” In Go—unlike chess, where the only way to win is to kill the king—aggressive players may not fare well. Balance is a primary criterion, says Chatterjee: “A move may get you more than half, but it may be the wrong move.” Pucciarello agrees. “If we negotiate the best possible price for an item with a vendor without thinking about what it will do to that vendor, then we may not have anyone to buy from in the future. That works with my customers as well. If I try to get the most out of them, I may not have a customer base in the future; they will go elsewhere or go broke,” he says. Asian executives who play Go frequently—sealing deals over boards instead of fairways—talk about it as a game of productivity. Securing corners is analogous to securing a niche in the domestic market. Fuseki moves are comparable to new product requirements. The endgame, where prisoners are exchanged, is like a trade surplus or deficit. Like diplomatic relations and tennis, Go requires good manners from its players. The game’s Chinese roots imbue it with tradition and etiquette (values that could cause hard-boiled Uncle Harry some trouble). In 1049, the Chinese writer Chang Ni compared a Go board with the universe. He believed the 361 intersections represented the 360 days in the Chinese lunar year, plus one, which represented the supreme being. The board’s four quadrants represented the four seasons. And the equal division of black and white stones paralleled the balance of yin and yang. Go players talk about patterns, balance, and symmetry because, well, the board and the stones have so few distinguishing features. Stones in familiar formations are your lifeboats and navigational tools. Similarly, maintaining symmetry keeps stones connected and impervious to invasion. If you don’t pay attention to stone formations, shicho (“the ladder”) will pin you to the edge again. “A good Go player has physical stamina, long-term dedication, the ability to learn, and the ability to lose,” says Chatterjee, who studies how players improve their games and writes books (Galactic Go, Cosmic Go) and articles (for American Go Journal and Go Winds) about his findings. For Chatterjee, both the study and the game itself are enticing. “I have always been fascinated with the concept of the infinite,” he says, describing mathematics —“number theory, in particular”—as a pursuit close to his heart. And Go plays to his strengths. “Remembering and using large chunks of knowledge—josekis, sequences— lets me plan and design at the macro level. Being able to http://www.northeastern.edu/magazine/0201/go.html[7/13/2012 12:58:42 PM] Go: With the Flow use my memory has always made Go seductive,” he says. But the game of Go is not his only passion. Chatterjee also writes about baseball (“Improvement by Spreading the Wealth—The Case of Home Runs in Major League Baseball,” in the Journal of Sports Economics), basketball (“Who Is the Greatest Rebounder of All Time?” in Chance magazine), and golf (“An Analysis of 1992 Performance Statistics at the USPGA Senior PGA and LPGA Tours,” in Science and Golf). “I study improvement,” says Chatterjee, who considers the topic his particular niche. “Improvement, progress, and what it all means.” For serious Go competitors—those who compete for the prestigious Samsung Cup, for example—improvement can mean winning significant prize money, the kind professional athletes see. Youth is no impediment. “The world’s best players are getting younger, with twentytwo- and twenty-three-year-olds dominating the tournaments,” says Chatterjee. In the world of Go, however, even straightforward proficiency has its rewards. At last summer’s China International Go Culture Gala, held in Guiyang, in southcentral China, a week of festivities concluded with the simultaneous playing of 2,001 Go games in the town square. Chatterjee was honored as the 2,001st competitor. “I played with the mayor of Guiyang!” Katy Kramer, MA’00, a freelance writer living in New Hampshire, writes this magazine’s “Husky Tracks.” http://www.northeastern.edu/magazine/0201/go.html[7/13/2012 12:58:42 PM]