Indian Philosophy on Matter and Idealism: - East

advertisement

INDIAN PHILOSOPHY ON MATTER

AND IDEALISM:

An Introduction

Boyd – 2010 (East-West IASP Project)

Context of this presentation

(Slide titles in red indicate the slide will not be part of the actual class

presentation . When the content, below is in red, it indicates that the

details need to be worked out and what is shown only outlines a direction to

be taken.)

Introductory type course in philosophy that focuses

on theories of knowledge (epistemology) and reality

(metaphysics)

We read two primary texts

Russell, The Problems of Philosophy

Strawson, Analysis and Metaphysics

This presentation will take place about a month into

the semester

Russell after a couple of introductory chapters turns

to the issue of the nature of matter. A central part of

this discussion is his “refutation” of idealism, which

was a prominent approach to philosophy in 1912.

Primarily focuses on G. Berkeley (1685-1753) and F.H.

Bradley (1846-1924)

Idealism reviewed

Idealism (?)

“Idealism consists in the assertion that there exist none but

thinking entities; the other things we think we perceive in

intuition being only presentations of the thinking entity to

which no object outside the latter can be found to

correspond.” Kant, Prolegomena)

Reality is spiritual (Dasgupta)

All existence has its core or foundation and being in the mind

G. Berkeley – Does a tree falling in a forest where no

one is there make a sound? (theistic idealism)

F.H. Bradley – Reality is one; there are no real

separate things; reality consists solely of idea or

experience (non-theistic idealism)

Bibliographical sources for further work

Two Philosophers of Idealism

F.H. Bradley (1846-1924)

Appearance and Reality (1893)

Essays on Truth and Reality (1914)

Writings on Logic and Metaphysics – Bradley, ed. Allard & Stock (1994)

Studies in the Metaphysics of Bradley, Saxena (1967)

An Introduction to Bradley’s Metaphysics, Mander (1994)

Shankara (c. 788-820 CE)

Shankara’s Crest-Jewel of Discrimination , 3rd edition. {(Prabhavananda,

Swami and Isherwood, Christopher. (Trans.). (1978). Vedanta Press}

The Vedānta Sūtras of Bādarāyaņa with the Commentary by Śańkara,

Parts 1 and 2. {Thibaut, George. (Trans). (1962)}

Indian Idealism, Dasgupta (1962)

Philosophies of India, Zimmer (1974)

An Introduction to Śańkara’s Theory of Knowledge, Devaraja, (1962)

“Idealist Refutations of Idealism,” Chakrabarti, Idealistic Studies (1991)

Focus: Shankara, but first a quick look at some of the relevant texts

Three (selective) passages from the Upanishads

Chāndogya Upanishad

Dialogue between one who is learned, and a

student

Monistic World-Soul, Ātman, is that immanent

reality found in all things

Aitareya Upanishad

The Self is in all – a pantheistic position

Para-Brahma is the source or means of empirical

knowledge as well as that which is not empirical –

all that exist owes their existence to Para-Brahma.

Finally, “Brahma is intelligence.”

Selective passages cont’d

Māņdūkya Upanishad

Om!—This syllable is this whole world.

Its further

explanation is: – The past, the present, the future –

everything is just the word Om. And whatever else that

transcends threefold time – that, too, is just the word Om.

For truly, everything here is Brahma; this self is Brahma. …

This is the lord of all. This is the all-knowing. This is the

inner controller. This is the source of all, for this is the

origin and the end of beings. Not inwardly cognitive, not

outwardly cognitive, not both-wise cognitive, not a

cognition-mass, not cognitive, not non-cognitive, unseen,

with which there can be no dealing, ungraspable, having no

distinctive mark, non-thinkable, that cannot be designated,

the essence of the assurance of which is the stating of

being one with the Self, the cessation of development,

tranquil, benign, … He is the Self. He should be discerned.

This is the Self with regard to the word Om, with regard to

its elements. … Thus Om is the Self indeed. He who knows

this, with his self enters the Self – yea, he who knows this!

Passage can be seen to present an absolute monism

Commentaries on Upanishads

Upanishads do not contain a systematic philosophy

or theology, hence sutras were developed by

subsequent thinkers

These sutras pull together the various ideas taught

in the Upanishads, and one of the greatest sutras is

by Bâdarâyana

However, because of the nature of a sutra and the

fact that they seldom identify the Upanishad they

are dealing with, commentaries were developed to

clarify a sutra

Shankara is credited for writing such a commentary and

developing a systematic philosophy that reflects the

monism we saw in the selective passages above

While Shankara advocated an absolute monism or strict

non-dualistic philosophy, he acknowledges two levels of

“reality”

Shankara

In the second sutra Bâdarâyana states “(Brahman is that) from

which the origin, &c. (i.e. the origin, subsistence, and dissolution)

of this (world proceed).” (Thibaut, 15)

According to Shankara this sutra means that “[t]hat omniscient

omnipotent cause from which proceed the origin, subsistence,

and dissolution of this world – which world is differentiated by

names and forms, contains many agents and enjoyers, is the

abode of the fruits of actions, these fruits having their definite

places, times, and causes, and the nature of whose arrangement

cannot even be conceived by the mind, that cause, we say is

Brahman.” (16)

He acknowledges that this world, the world of sense experience,

exists, but its existence is different than the existence of

Brahman, which has no place for empirical data.

The reality of ‘this’ world should not blind us to an even greater

reality, and this latter reality is greater because it is true reality –

a reality that is not based on or found in the empirical

Shankara continues, “wrong knowledge itself

is removed by the knowledge of one’s Self

being one with the Self of Brahman.” (30)

This ‘oneness’ is nothing less than complete

identity – an absolute monism.

This reality is greater than the reality of the

empirical world because the latter is based

upon wrong knowledge whereas the former is

based upon truth – the teachings of

revelation found in the scriptures

Shankara’s Crest-Jewel of Discrimination

The first qualification attaining liberation is the ability to

distinguish between the eternal and the non-eternal.

“Brahman is real; the universe is unreal. A firm conviction that

this is so is called discrimination between the eternal and the

non-eternal.” (35)

Furthermore, Brahman and Atman are one:

“Atman is pure consciousness … The Atman is the witness,

infinite consciousness, revealer of all things but distinct from

all … It is the eternal reality, omnipresent, all-pervading, the

subtlest of all subtleties. It has neither inside nor outside. It is

the real I, hidden in the shrine of the heart. … He is the truth.

He is existence and knowledge. He is absolute. He is pure and

self-existent. He is eternal, unending joy. He is none other

than the Atman. The Atman is one with Brahman: this is the

highest truth. Brahman alone is real. There is not but He. …

He is pure consciousness, free from any taint. He is tranquility

itself. … He does not change. He is joy forever.” (69-71)

Shankara’s system as idealism

Two questions:

While the passages above show that Shankara

was an absolute monist, how is Shankara’s system

a form of idealism?

Do the objections that Russell raises concerning

the idealism of Berkeley and Bradley affect

Shankara’s form of idealism?

Shankara as idealism: overview

“Idealism consists in the assertion that there exists

none but thinking entities; the other things we think

we perceive in intuition being only presentations of

the thinking entity to which no object outside the

latter can be found to correspond.” (Dasgupta, 23)

Shankara starts with consciousness defined

ultimately as Brahman

This concept of Brahman is adequate to give an

explanation for our empirical evidence of a physical

world, i.e., illusion (māyā) due to ignorance

Because his metaphysics is an absolute monism, real

reality consists of one thinking entity – Brahman;

hence Shankara avoids a subjective form of idealism

Shankara’s argument

P1 – Brahman, a conscious entity, is all reality;

P2 – Brahman is the cause of all, including māyā,

and is present in all our cognitions

P3 – All experience begins and continues due to

an erroneous belief that the “self” is identified

with the body or the objects of the senses

P4 – Individual things, including matter, are only

appearance

Concl – Matter does not exist; hence the world

“only phenomenally exists as mere objects of

name and form” (Dasgupta, 165) This conclusion

is a form of idealism

Sub-arguments

Each premise of the previous argument is

supported by its own set of evidence

However, premise 1 is foundational to his

sub-arguments for premises 2 through 4

His evidence for premise one is the selfrevelation of Brahman in the sacred texts

These sub-arguments need to be developed

and presented

Russell’s criticism of idealism

revisited

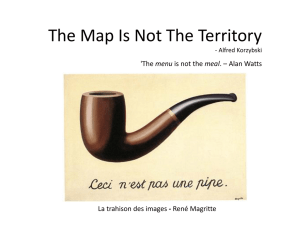

Table - example

Sense-data

Acknowledges limitations in our knowledge,

but claims we all agree that something is

there

Russell’s criticism needs further development

Shankara’ Position untouched

1st approach: Shankara & the Principle of

Non-Contradiction

Embraces the principle of contradiction for all

levels except that ultimate reality of Brahman

The law does not apply at this level of absolute

monism, which embraces sat (Being) and asat

(non-Being) equally and at the same time

Similar to the intuitionalists (logical) move of

embracing the three laws of thought, except in

cases that involve the infinite where they may

reject Law of Non-Contradiction {~(P & ~P)} and

Law of the Excluded Middle {P v ~P} [Law of

Identity has other problems]

Russell and Shankara cont’d

2nd approach: Developed argument (Arindam

Chakrabarti)

Three-level theory of unreality

Unreality of the absolutely unappearable nonentities

(the absurd)

Unreality of the individually subjective illusions (the

illusory)

Unreality of the empirical that is more real than a

dream but less real than pure undifferentiated

consciousness (the phenomenal)

Shankara’s deeper metaphysical ideal – a nevernegated pure consciousness is really real

Russell and Shankara cont’d: Best

approach

3rd approach: Category Mistake

Given Shankara’s starting point, it appears that his

position is isolated from Russell’s object that there

must be a table there even if we do not “know”

the table

In some way for Russell, the object presents the

sense-data, but for Shankara the sense-data is not

presented by the object

Sense-data objection by Russell seems to be a

category mistake when applied to Shankara

The rest of the story

The Vedantic School of Indian philosophy is not

the only story told, nor is Shankara the only story

told within the Vedantic school; hence the rest of

the story must address individuals such as

Ramanuja (1017-1137), a modified monist - but

not an idealist, as well as those other schools as

they say something about matter and reality,

e.g., Aśvaghosha’s Buddhism

Built into syllabus for the fall 2010

Three class periods to present some of these other

schools as regards matter

Latter in the semester – three more class periods will

address issues such as methodology and reasoning in

Indian philosophy