Job Churn

Business Demography

and

Job Churn Workshop

May 2011

Outline

- The Motivation

- The Sources

- The Methodology

- The Story (a chapter or two)

- The Possibilities

John.Dunne@cso.ie

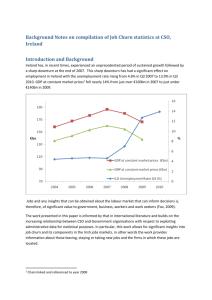

The Motivation - Context

€bn

190

% 16

14

170

12

150

10

130

8

6

110

GDP at constant market prices (€bn)

90

GNP at constant market prices (€bn)

ILO Unemployment Rates Q3 (%)

70

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

Increased demand for information on jobs

Less financial resources

New opportunities to exploit administrative data

A methodology already outlined in research literature

4

2

0

The Motivation – Policy value

Contribute to

Identification of employment opportunities (Short term)

Evaluating and targeting (re)training

Jobs policy (Long term)

(Medium term)

The Sources – the analysis file

CSO

Business

Register

EMR ID

CBR ID

Legal form

Activity

Revenue

Employer

Employee Tax

returns

EMR ID

PPSN

Class

Weeks

Pay

DSP

Client record

System

PPSN

DOB

Gender

Nationality

Integrated and depersonalised for multi-purpose analysis

SPP35 Analysis file for each reference year

CSOPPSN

CBR ID

Month of birth, Sex, Nationality

Activity (NACE Rev 2), Legal form

Weeks, Reckonable pay

The Sources - strengths

– Links information on employer and employees

– Comprehensive

– High quality

– Consistent

The Sources - weaknesses

For administrative purposes

As is (warts and all / legal record)

Not perfect

No point in time (Concurrent v Consecutive records, seasonality)

Timeliness (10 months after reference period end)

Business register (on going quality enhancement)

The Sources – Added opportunities

Other indicators

– Job volume

– Job value

(Sum of weeks | years worked)

(Sum of reckonable pay recorded)

– Job quality

(Mean weekly reckonable pay)

The Methodology – illustrating by simple example

A firm has 10 paid employees

on books in 2008

An firm has 12 paid employees

on books in 2009

The firm has 4 paid workers on

books in 2009 that don’t

exist in 2008 (Hirings)

The firm has 2 paid workers on

books in 2008 that don’t

exist in 2009 (Separations)

Ref Year 2009

Hirings (H) = 4

Job Creation (JC) = 2

Separations (S) = 2

Job Destruction (JD) = 0

Job Churn (CH) = 4

The Methodology – building blocks

For two timepoints/periods in enterprise/employee data

At the person level

Hirings (H)

Separations (S)

Job stayers (JS)

At the enterprise level

Job creation (JC)

Job destruction (JD)

An identity

The Methodology – calculations (job reallocation / job turnover)

Total job reallocation (REALJ) refers to the sum of job creation (JC) and job

destruction (JD) for a group of enterprises.

Excess job reallocation (EXCJ) for a group of enterprises is defined as the

difference between total job reallocation (REALJ) and the absolute net

change in total employment ( |JC - JD| ), for group j at period t.

Excess job reallocation provides a measure of the offsetting job creation and

job destruction within a group of firms.

The Methodology– calculations (worker reallocation / worker turnover)

Total worker reallocation (REALW) is calculated by summing hirings (H)

and separations (S) over all members of a specified group, the group

can be defined either by a group of enterprises or on a set of

particular demographic characteristics (age, gender etc).

Excess worker reallocation (REALW) for a group is defined as the

difference between total worker reallocation (REALW) and the group’s

absolute net change in employment (|H - S|). So for group j at period

t,

Excess worker reallocation provides a useful measure of the number of

excess new person job matches over and above the minimum necessary to

accommodate net employment growth/decline; in other words, it reflects

the reallocation of job matches (reshuffling of jobs and workers) within the

same group (Bassanini & Marianna, 2009).

The Methodology – calculations (Job churn / churning flows)

At the enterprise level or any group of enterprises, churning flows

(CH) is the difference between excess worker reallocation and excess

job reallocation.

Churning flows represent labour reallocation arising from enterprises

churning workers through continuing jobs or employees quitting and

being replaced on those jobs. So for group j in period t

The Story – Chapter JCA02 (Firm based components)

Primary components for Business Economy (Employment records)

900000

Hirings

Separations

800000

Job creation

700000

Job destruction

600000

500000

400000

300000

200000

100000

0

2006

2007

2008

People less likely to leave their jobs in a downturn

- > Job churn is pro cyclical

2009

The Story – Chapter JCA02 (A comparison - Environment)

Finland

- end of 80s high growth and overheating

-deep recession at start of 90s due to internal and external shocks that included

collapse of Soviet Union, slowdown in Western Europe, severe banking crisis due to

deregulation. ( Ilmakunnas 2001 )

The Story – Chapter JCA02 (A comparison – Primary components)

The Story – Chapter JCA02 (Selected Sectors)

Sectoral view

Sector C Manufacturing

Sector E Water supply, sewage ....

Sector F Construction

Sector G Wholesale and retail trade

Sector H Transportation and storage

Sector I Accommodation and food

Sector J Information and communication

The Story – Chapter JCA01 ( Who are the separations? )

The Story – Chapter JCA03 (Re-employment of persons separating)

Primary separations

With no new

employment

Primary

separations

With new

employment

Construction

Business

economy

of companies

holding (B to

Industry

to(F)

E) services

Business (B

economy

excludingexcluding

activitiesactivities

of holding

companies

(G toNumber

N,-642)

24223

68155

43932

19053

52830

33777

N,-642) 2006

2006

Number

113296

362803

249507

cent

(36)

(100)

(64)

2006 Per

Number

156572

483788

327216

Per

cent

(31)

(100)

(69)

29011

79224

50213

2007 Number

22152

57998

35846

Per cent

(32)

(100)

(68)

2007

Number

112657

395016

282359

(37)

(63)

cent

(38)

(100)

(62)

2007 Per

Number

163820

532238

368418

Per

(29)

(100)

(71)

43424

94859

51435

2008 Number

24416

59436

35020

Per cent

cent

(31)

(100)

(69)

2008

Number

137166

431906

294740

cent

(46)

(100)

(54)

(41)

(59)

2008 Per

Number

205006

586201

381195

Per

(32)

(100)

(68)

58952

93795

34843

2009 Number

35027

68436

33409

Per cent

cent

(35)

(100)

(65)

2009

Number

187274

438509

251235

(63)

(37)

cent

(51)

(100)

(49)

2009 Per

Number

281253

600740

319487

Per

(43)

(100)

(57)

Per cent

cent

(47)

(100)

(53)

The Story – Chapter JCA04 (Where are separations re-employed?)

Sectoral distribution of re-employed separations (2009)

B to N,-642

C

F

G

I

N

Business economy excluding activities of holding companies (B to N,-642)

Number

270112

25792

22024

78360

Per cent

(100)

(10)

(8)

(29)

43788

(16)

37207

(14)

Manufacturing (C)

Number

Per cent

26175

(100)

10485

(40)

1532

(6)

6394

(24)

1794

(7)

2522

(10)

Construction (F)

Number

Per cent

30493

(100)

2772

(9)

13522

(44)

3706

(12)

2177

(7)

4260

(14)

Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles (G)

Number

72824

4860

1751

42571

Per cent

(100)

(7)

(2)

(58)

7479

(10)

6320

(9)

Accommodation and food service activities (I)

Number

43975

1732

Per cent

(100)

(4)

962

(2)

9002

(20)

23590

(54)

4157

(9)

Administrative and support service activities (N)

Number

39872

2842

Per cent

(100)

(7)

2160

(5)

7384

(19)

4828

(12)

13365

(34)

The Story – (Where might new jobs come from?)

Ilmakunnas (2001)

The Possibilities – (Business register, geo spatial, other data sources)

Business characteristics (Location/county,

firm status –

expanding/contracting, trade indicator, coverage

beyond business economy, Foreign controlled)

Geo- spatial (Introduction of

post codes, employee

and employer location, admin data quality)

Other data sources (

FAS, Live Register, .... )

The References

Bassanini, A., & Marianna, P. (2009). Looking inside the perpetual motion machine: job and

worker flows in OECD countries. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org.

Burgess, S., Lane, J., & Stevens, D. (2000). Job Flows, Worker Flows and Churning. Journal

of Labor Economics , 18 (3).

Fox, R. (2009, June). Job Opportunities in the Downturn. Retrieved March 15, 2011, from

http://www.fas.ie/NR/rdonlyres/9ABC5EE1-CF20-4AA5-ACA4C5B81DD9FE5E/793/jobsdownturn96.pdf

Guertzgen, N. (2007). Job and Worker reallocation in German establishments: the role of

employers' wage policies and labour market equilibriums. Discussion paper, Centre for

European Economic Research, Mannheim.

Ilmakunnas, P., & Maliranta, M. (2001). The turnover of jobs and workers in a deep recession:

evidence from the Finnish business sector. Helsinki School of Economics and Business

Administration; The Research Institute of the Finnish Economy. Helsinki: The Research

Institute of the Finnish Economy.

Lawless M & Murphy A, (2008). Job turnover in Irish Manufacturing 1972-2006. The

Economic and Social Review, Vol. 39, No. 3, Winter 2008, pp235 - 256

Li, D. (2010). Job reallocation and labour mobility among heterogeneous firms in Norway.

Working Paper, Ragnar Frisch Centre for Economic Research.

http://www.cso.ie/surveysandmethodologies/surveys/construction/Jobchurn.htm

Thank you

John.Dunne@cso.ie