Labor Supply : Theory and Evidence

advertisement

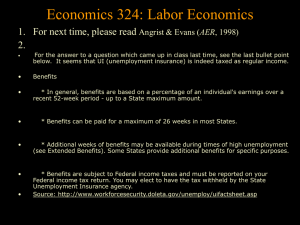

LABOR SUPPLY : THEORY AND EVIDENCE 1 Hewi-Lin Chuang, Ph.D. 2014/02/26 觀光帶動就業 嘉市失業率全國最低 桃園縣去年失業率4.3% 並列全國最高 2014-01-22 【中廣新聞/黃悅嬌】 2014-02-17 【自由時報/邱奕統】 行政院主計總處公布一百零二年平均失業率百分之四點一八,各縣 市以嘉義市失業率百分之三點九最低,主要為觀光業成長,帶動商 業活動就業機會增加。 而桃園縣去年的失業率為四.三%,不僅是六都中失業率最高的, 更與南投、宜蘭縣並列全國最高。對此,勞動局長簡秀蓮說,桃園 縣內提供的工作機會遠高於需求,平均每名求職者可有三個工作選 擇,因多數職缺都以勞力密集的第一線作業為主,讓年輕人沒有意 願投入,企業主不得不引進外勞填補勞動缺口,而全縣現有的八萬 三千名外勞也間接衝擊本國就業人口。 資料來源 http://tw.news.yahoo.com/%E6%A1%83%E5%9C%92%E7%B8%A3%E5%8E%BB%E5%B9%B4%E5%A4%B1%E6%A 5%AD%E7%8E%874-3-%E4%B8%A6%E5%88%97%E5%85%A8%E5%9C%8B%E6%9C%80%E9%AB%98004046160.html http://tw.news.yahoo.com/%E8%A7%80%E5%85%89%E5%B8%B6%E5%8B%95%E5%B0%B1%E6%A5%AD2 %E5%98%89%E5%B8%82%E5%A4%B1%E6%A5%AD%E7%8E%87%E5%85%A8%E5%9C%8B%E6%9C%80%E4% BD%8E-035915102.html 失業率創新高 薪資倒退嚕 非青貧即窮忙 2014-01-25【自立晚報/郭玉屏】 據行政院主計總處2013年失業率相關統計顯示,15-24歲者在2013年 的平均失業率高達13.17%!更創下近10年來新高! 由教育程度區分失業週數,亦看出令人擔憂的高學歷、高失業週數之 情況,據勞委會之統計,2013年高中職學歷年平均失業週數為24.85 週、大專以上之年平均失業週數為27.32週,亦即較高學歷之民眾在 等待新工作或轉職之時間除了逼近7個月,等待期也偏高近3週,由此 可知高學歷的求轉職不易,關鍵原因之一為高等教育的產學失衡。 2013年的就業狀況也不是只有青年遭殃,普遍性的全國受僱者「薪」 情亦屬不佳,據勞委會2013年統計資料顯示,我國國人受僱薪資在不 到3萬元者佔總受僱者比例高達41.6%、亦即全國有將近4成的上班族 每個月的荷包進帳不到3萬元。 資料來源 3 http://tw.news.yahoo.com/%E5%A4%B1%E6%A5%AD%E7%8E%87%E5%89%B5%E6%96%B0%E9%AB%98%E9%A6%AC%E5%90%91%E9%9D%92%E5%B9%B4%E8%AA%AA%E6%81%AD%E5%96%9C%E7%99%BC%E8 %B2%A1-185204407.html LABOR SUPPLY : THEORY AND EVIDENCE Labor supply decisions can be roughly divided into two categories: (1) Decisions about whether to work at all, if so, how long to work. (2) Decisions about the occupation or general class of occupation in which to seek offers and the geographical area in which offers should be sought. 4 1. SOME STYLIZED FACTS ABOUT LABOR SUPPLY Trends in LFP: (1) 女性勞動參與率由1964年的34%逐漸上升至 1986年的45%,1986-1999年則維持在45%左右, 1999年開始逐漸上升,至2013年已達到50.46%。 男性勞參率由1978年的77.96%逐漸下降至2013年的66.74%。 (2) 15-19歲組勞參率由1978年的45%顯著下降至 2003 年的12%,至2013年都維持在10%上下。 20-24歲組勞參率由1978年的65%逐漸下降至2005年的53%, 自2005年始到2013年為止都在53%上下起伏。 其他各年齡組均呈現上升或持平之趨勢。 5 台灣歷年勞動力參與率-按年齡組別分 15~24歲 25~44歲 45~64歲 65歲以上 總 男 女 總 男 女 總 男 女 總 男 女 1978 53.53 56.79 50.78 69.54 97.39 40.90 61.01 86.43 27.07 9.48 16.82 2.47 1979 53.11 55.96 50.74 69.69 97.55 41.05 61.24 86.32 28.03 9.26 16.74 2.00 1980 51.84 53.87 50.20 69.93 97.52 41.62 60.55 84.94 28.62 8.48 15.27 1.78 1981 50.94 52.53 49.65 69.74 97.54 41.27 60.05 84.67 28.46 8.55 15.24 1.86 1982 50.25 51.73 49.05 70.37 97.32 42.81 59.78 83.80 29.23 8.48 14.88 2.01 1983 50.75 51.49 50.15 72.47 97.11 47.34 60.52 83.07 32.24 9.11 15.35 2.70 1984 50.25 50.54 50.02 73.66 97.18 49.68 60.98 82.87 33.99 9.07 15.04 2.80 1985 49.05 48.90 49.16 74.01 96.91 50.62 60.55 81.98 34.51 9.74 15.72 3.36 1986 49.57 48.52 50.44 75.55 96.74 53.91 60.61 81.04 36.20 10.53 16.66 3.89 1987 49.31 47.98 50.41 76.61 96.74 56.07 61.18 81.65 37.10 10.59 16.70 3.88 1988 47.10 45.43 48.47 76.44 96.86 55.59 60.87 81.92 36.48 9.64 15.21 3.43 1989 46.29 44.69 47.61 76.51 96.77 55.84 60.64 82.13 36.08 10.34 16.03 3.92 1990 43.93 42.19 45.36 76.19 96.53 55.43 59.65 81.08 35.62 9.77 14.80 4.02 1991 42.63 41.05 43.93 76.53 96.57 56.06 59.74 81.80 35.54 9.93 14.92 4.12 1992 41.55 40.83 42.15 77.39 96.61 57.71 60.24 82.39 36.34 9.69 14.48 4.07 1993 39.65 38.46 40.68 77.68 96.28 58.74 60.09 82.17 36.63 9.83 14.72 4.00 1994 39.78 38.84 40.60 78.15 96.12 59.87 60.24 82.37 37.12 9.68 14.38 4.04 6 台灣歷年勞動力參與率-按年齡組別分(續) 15~24歲 25~44歲 45~64歲 65歲以上 總 男 女 總 男 女 總 男 女 總 男 女 1995 38.46 37.93 38.93 78.21 95.83 60.35 60.83 82.96 38.11 9.79 14.39 4.24 1996 37.40 36.44 38.25 78.60 95.41 61.60 60.87 82.44 39.04 8.95 13.05 3.98 1997 36.88 36.07 37.59 78.80 95.38 62.04 61.20 83.01 39.34 8.76 12.87 3.86 1998 35.96 34.76 37.01 79.17 95.18 62.98 60.81 82.80 38.91 8.51 12.45 3.89 1999 36.56 35.29 37.69 79.36 94.81 63.72 60.35 81.09 39.70 7.92 11.49 3.84 2000 36.28 35.28 37.18 79.60 94.54 64.52 59.80 80.12 39.62 7.71 11.25 3.73 2001 35.47 33.56 37.21 79.71 94.09 65.31 59.13 78.93 39.47 7.39 10.91 3.52 2002 35.29 32.75 37.59 79.97 93.57 66.33 59.04 78.35 39.91 7.79 11.54 3.78 2003 33.91 30.79 36.76 80.34 93.12 67.55 59.58 78.05 41.31 7.78 11.38 4.01 2004 33.52 30.77 36.05 81.25 93.30 69.25 59.96 78.10 42.03 7.42 10.83 3.93 2005 32.61 29.65 35.35 81.87 93.19 70.62 60.24 78.12 42.59 7.27 10.66 3.86 2006 31.48 28.46 34.35 82.98 93.34 72.75 60.01 77.61 42.68 7.58 11.18 4.04 2007 31.10 28.13 33.96 83.41 92.99 73.98 60.55 77.25 44.13 8.13 11.95 4.45 2008 30.17 27.81 32.47 83.81 92.94 74.83 60.83 76.89 45.08 8.10 11.74 4.64 2009 28.62 25.72 31.48 84.19 92.98 75.58 60.25 75.65 45.17 8.05 11.95 4.4 2010 28.78 26.46 31.06 84.72 93.15 76.51 60.31 75.36 45.61 8.09 12.07 4.43 2011 28.56 26.43 30.7 85.56 93.89 77.53 60.36 75.54 45.59 7.93 12 2012 29.08 26.94 31.23 86.33 94.6 78.38 60.48 75.39 46.01 8.1 12.46 4.23 7 4.2 2013 29.58 28.32 30.83 86.64 94.49 79.09 60.73 74.82 47.08 8.34 12.82 4.38 台灣歷年勞動力參與率-按年齡組別分 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 1978 1983 15~24歲 1988 1993 25~44歲 1998 45~64歲 2003 2008 65歲以上 2013 8 台灣歷年勞動力參與率-按教育組別分 國中及以下 高中職 大專及以上 總 男 女 總 男 女 總 男 女 1978 59.36 83.86 37.13 54.36 62.82 43.64 63.34 68.37 53.79 1979 59.17 83.74 37.05 55.29 64.27 44.24 62.92 68.56 52.48 1980 58.43 82.82 36.67 55.07 64.32 44.25 64.08 70.19 53.03 1981 57.61 81.99 35.85 55.33 65.22 43.90 64.83 71.15 53.91 1982 57.60 81.68 36.09 55.75 65.62 44.61 65.09 71.02 54.85 1983 58.93 81.36 38.92 57.15 66.61 46.66 66.09 71.26 57.44 1984 59.17 80.61 40.06 58.13 67.72 47.66 66.51 71.84 57.67 1985 58.80 79.78 40.04 57.96 67.55 47.60 66.77 71.87 58.42 1986 59.43 79.00 41.81 59.46 68.40 50.04 67.35 72.20 59.47 1987 59.72 79.04 42.29 60.46 69.20 51.27 67.74 72.02 61.17 1988 58.46 78.35 40.61 60.42 69.44 51.02 67.58 72.27 60.45 1989 57.96 77.88 40.07 60.91 70.51 50.99 67.52 72.54 59.94 1990 56.69 76.86 38.71 60.51 70.48 50.23 66.40 71.19 59.29 1991 56.22 76.40 38.12 60.65 70.66 50.39 66.80 71.46 60.01 1992 56.13 75.91 38.33 60.93 71.23 50.44 67.22 72.18 60.12 1993 55.11 74.65 37.63 60.70 70.45 50.76 66.71 71.32 60.22 1994 54.80 73.96 37.56 61.00 70.90 50.94 67.52 71.21 62.42 9 台灣歷年勞動力參與率-按教育組別分(續) 國中及以下 高中職 大專及以上 總 男 女 總 男 女 總 男 女 1995 54.04 73.03 36.88 60.94 70.91 50.82 67.65 71.50 62.60 1996 52.69 71.04 36.24 61.12 70.64 51.40 68.27 72.10 63.45 1997 51.98 70.02 35.82 61.08 71.09 50.96 68.75 73.21 63.24 1998 51.05 69.06 34.84 61.12 71.11 51.11 68.36 72.70 63.16 1999 50.26 67.71 34.62 61.36 71.21 51.50 67.98 71.96 63.21 2000 49.42 66.73 33.94 61.40 71.30 51.49 67.65 71.26 63.35 2001 48.51 65.70 33.14 61.38 70.68 52.14 66.40 69.79 62.41 2002 47.96 64.95 32.77 61.90 71.14 52.81 65.91 69.16 62.14 2003 47.24 63.47 32.64 62.43 71.64 53.42 65.43 68.51 61.95 2004 46.39 62.38 31.96 63.41 72.66 54.43 65.75 68.83 62.32 2005 45.53 61.43 31.24 63.45 72.67 54.46 66.40 69.18 63.35 2006 44.34 59.72 30.53 63.52 72.34 54.93 67.38 70.21 64.30 2007 43.88 59.01 30.34 63.95 72.24 55.82 67.63 70.36 64.71 2008 42.87 57.85 29.46 63.64 72.02 55.40 68.18 70.85 65.35 2009 41.67 56.22 28.61 62.61 71.13 54.22 68.4 70.82 65.89 2010 41.62 56 28.67 62.25 70.87 53.78 68.43 71.17 65.64 2011 41.18 55.99 27.62 62.36 70.93 53.97 68.23 71.29 10 65.19 2012 41.25 55.95 27.34 62.3 71.19 53.51 68 71.37 64.78 2013 41.5 55.64 27.51 61.82 70.6 53.02 67.77 71.76 64.14 台灣歷年勞動力參與率-按教育組別分 70 65 60 55 50 45 40 1978 1983 1988 國中以下 1993 1998 高中(職) 2003 大專以上 2008 2013 11 台灣歷年勞動力參與率-按婚姻別分 有配偶或同居 未 婚 離婚、分居或喪偶 總 男 女 總 男 女 總 男 女 1978 59.18 58.44 60.19 60.50 89.60 31.94 30.88 55.07 19.00 1979 61.38 62.26 60.30 60.48 89.56 31.87 29.13 52.65 17.87 1980 60.20 60.80 59.48 60.36 88.95 32.19 28.49 50.56 18.21 1981 59.75 60.41 58.95 59.91 88.65 31.72 28.32 49.39 18.45 1982 59.24 59.93 58.41 60.29 88.13 32.97 28.35 48.66 19.07 1983 59.58 59.82 59.29 62.12 87.77 36.96 30.25 49.52 21.13 1984 59.04 59.49 58.50 63.06 87.44 39.04 31.85 50.14 23.14 1985 58.31 58.76 57.78 63.10 86.91 39.68 32.10 49.81 23.63 1986 58.49 58.47 58.51 64.42 86.74 42.52 33.05 49.83 24.79 1987 58.98 59.17 58.75 65.07 86.55 43.91 33.46 49.77 25.49 1988 58.17 58.80 57.42 64.33 85.91 42.98 33.31 49.61 25.48 1989 58.11 59.13 56.88 64.16 85.63 42.94 33.96 50.72 25.73 1990 56.78 58.01 55.30 63.40 84.76 42.30 34.44 51.06 26.07 1991 56.30 57.77 54.53 63.50 84.84 42.47 34.90 51.20 26.69 1992 56.01 58.04 53.55 64.00 84.67 43.65 35.20 51.55 26.9412 1993 54.58 56.33 52.45 63.98 83.97 44.29 34.62 50.18 26.72 1994 54.96 56.92 52.56 64.02 83.20 45.13 34.53 50.05 26.71 台灣歷年勞動力參與率-按婚姻別分(續) 有配偶或同居 未 婚 離婚、分居或喪偶 總 男 女 總 男 女 總 男 女 1995 54.60 56.65 52.12 63.84 82.80 45.18 34.80 50.50 26.87 1996 54.14 55.96 51.94 63.71 81.73 45.95 34.91 50.52 27.17 1997 54.01 56.27 51.32 63.68 81.55 46.09 34.41 49.53 26.89 1998 53.85 55.83 51.50 63.45 81.12 46.06 33.75 48.43 26.70 1999 54.51 56.28 52.40 62.89 79.80 46.28 33.66 48.42 26.50 2000 54.69 56.35 52.71 62.40 79.00 46.14 33.97 48.79 26.68 2001 54.25 55.33 52.98 62.02 78.00 46.26 33.60 48.04 26.56 2002 54.85 55.67 53.89 61.91 77.37 46.64 34.15 48.93 26.88 2003 55.04 55.49 54.52 61.78 76.67 47.10 35.10 49.53 27.87 2004 56.00 56.62 55.28 61.92 76.21 47.77 35.56 50.39 28.12 2005 56.86 57.18 56.49 61.72 75.77 47.75 35.87 50.19 28.97 2006 57.38 57.56 57.17 61.70 75.12 48.35 36.49 51.59 29.24 2007 58.02 58.14 57.89 61.84 74.68 49.10 37.19 51.59 30.22 2008 58.64 58.88 58.38 61.53 73.99 49.11 37.59 51.60 30.88 2009 58.81 58.88 58.74 60.93 73.05 48.92 37.52 51.11 30.93 2010 59.74 60.01 59.43 60.7 72.54 49.03 37.63 51.78 30.76 13 2011 60.39 60.62 60.14 60.6 72.37 48.97 37.33 52.43 30.17 2012 60.95 61.29 60.57 60.51 72.14 49.05 37.87 53.34 30.35 台灣歷年勞動力參與率-按婚姻別分 70 65 60 55 50 45 40 35 30 25 1978 1983 1988 未婚 1993 有偶或同居 1998 2003 離婚、分居或喪偶 2008 2013 14 歷年五月台灣地區有偶婦女勞動參與率 總平均 女性平均 有偶婦女平均 子女均在6歲以 上有偶婦女 有未滿6歲子女 有偶婦女 尚無子女有 偶婦女 69 58.26 39.25 33.23 35.64 28.90 39.10 70 57.82 38.76 31.42 32.75 28.26 39.30 71 57.93 39.30 31.51 32.29 28.99 41.12 72 59.26 42.12 35.53 35.70 33.40 48.89 73 59.72 43.30 38.74 38.55 37.34 50.88 74 59.49 43.46 39.84 39.63 39.07 48.95 75 60.37 45.51 41.82 41.85 40.55 50.62 76 60.93 46.54 43.74 43.18 42.95 56.75 77 60.21 45.56 42.66 41.82 42.29 56.55 78 60.12 45.35 43.65 42.35 44.64 54.79 79 59.24 44.50 42.49 41.04 43.69 55.21 80 59.11 44.39 44.00 42.66 44.36 60.50 81 59.34 44.83 43.23 42.49 42.30 58.24 82 58.82 44.89 44.39 43.78 42.99 59.71 83 58.96 45.40 45.41 44.03 45.73 64.16 15 84 58.71 45.34 45.75 44.45 45.75 65.01 85 58.44 45.76 47.11 45.70 48.15 62.66 項目 年 歷年五月台灣地區有偶婦女勞動參與率(續) 總平均 女性平均 有偶婦女平均 子女均在6歲以 上有偶婦女 有未滿6歲子女 有偶婦女 尚無子女有 偶婦女 86 58.33 45.64 46.98 45.48 48.16 62.42 87 58.04 45.60 46.50 44.20 49.60 65.58 88 57.93 46.03 46.82 44.87 49.24 64.99 89 57.68 46.02 46.34 43.54 51.39 65.97 90 57.23 46.10 46.48 43.23 52.99 66.76 91 57.34 46.59 47.30 44.39 53.57 63.94 92 57.34 47.14 47.34 44.69 53.46 64.30 93 57.66 47.71 47.84 44.92 54.15 69.37 94 57.78 48.12 47.88 44.54 55.64 71.21 95 57.92 48.68 48.38 44.67 58.14 71.31 96 58.25 49.44 49.57 45.90 61.18 70.09 97 58.28 49.67 49.38 45.18 64.14 70.34 98 57.90 49.62 48.52 44.72 60.85 70.83 99 58.07 49.89 48.74 45.27 60.03 69.88 100 58.17 49.97 48.89 44.87 61.87 101 58.35 50.19 49.05 44.76 63.89 75.72 16 74.22 102 58.43 50.46 45.46 41.41 62.22 70.94 項目 年 17 Trends in Hours of Work: 平均每人每週主要工作工時在1993-2000年間均為46小 時左右,在2001-2007年維持在45小時附近,到2012年 時下降至為43.69小時。 男性平均工時由1978年的每週50小時下降至2003年的 44.96小時,2004-2007年稍微增加至45.46,到2012年又 降為為每週44.06小時。 女性平均工時則由1978年的每週46小時上升為1993年的 46.47小時,之後下降,至2012年時下降到43.21小時。 18 臺灣地區就業者平均每人每週主要工作時數 總計 男 女 總計 男 女 1993 47.36 47.90 46.47 2003 44.75 44.96 44.44 1994 46.18 46.65 45.42 2004 45.14 45.48 44.67 1995 47.02 47.46 46.31 2005 44.97 45.34 44.46 1996 46.46 46.78 45.97 2006 45.12 45.56 44.53 1997 45.26 45.51 44.87 2007 45.02 45.46 44.45 1998 46.34 46.56 45.99 2008 43.83 44.19 43.35 1999 46.30 46.45 46.07 2009 43.42 43.60 43.19 2000 46.09 46.25 45.86 2010 43.60 43.96 43.15 2001 44.93 45.05 44.74 2011 43.39 43.79 42.87 2002 44.64 44.74 44.50 2012 43.69 44.06 43.21 19 臺灣地區就業者平均每人每週主要工作時數 20 2. A THEORY OF THE DECISION TO WORK The decision to work is ultimately a decision about how to spend time. Spend time in pleasurable leisure activities Use time to work (working for pay) The discretionary time we have (24 hours – time spent eating and sleeping) can be allocated to either work or leisure. Demand for Leisure Supply of Labor. 21 Basically, the demand for a good is a function of three factors: 1. The opportunity cost of the good. 2. One’s level of wealth. 3. One’s set of preference. The demand(D) for a normal good can be characterized as a function of opportunity cost(C) and wealth(V) D = f(C, V) 22 Where f depends on preferences. Demand for Leisure: (1) The opportunity cost of an hour of leisure is very closely related to one’s wage rate. For simplicity, we shall say that leisure’s opportunity cost is the wage rate. (2) Economists often use total income as an indicator of total wealth, since the two are conceptually so closely related. Demand for leisure function becomes DL = f(W, Y) 23 w (1) If income increases, holding wages(and f) constant, the demand for leisure goes up. If income increases(decreases), holding wages constant, hours of work will go down(up). Income effect on hours of work is negative. H 0 Income Effect = Y W 24 THE EFFECT OF A CHANGE IN NONLABOR INCOME ON HOURS OF WORK Consumption ($) F1 F0 $200 P1 U1 P0 U0 $100 E1 E0 70 80 110 Hours of Leisure An increase in nonlabor income leads to a parallel, upward shift in the budget line, moving the worker from point P0 to point P1. If leisure is a normal good, hours of work fall. 25 THE EFFECT OF A CHANGE IN NONLABOR INCOME ON HOURS OF WORK Consumption ($) F1 F0 P1 U1 P0 $200 E1 U0 $100 E0 60 70 110 An increase in nonlabor income leads to a parallel, upward shift in the budget line, moving the worker from point P0 to point P1. If leisure is inferior, hours of work increase. 26 (2) If income is held constant, an increase(decrease) in the wage rate will reduce(increase)the demand for leisure, thereby increasing (decreasing)work incentives. Substitution effect on hours of work is positive. Substitution Effect = H W Y 0 27 Both Effect Occur When Wages Rise Income effect: For a given level of work effort, he/she now has a greater command over resources than before because more income is received for any given number of hours of work. Substitution effect: The wage increase raises the opportunity costs of leisure, and thereby increases hours of work. 28 MORE LEISURE AT A HIGHER WAGE When the income effect dominates the substitution effect, the worker increases hours of leisure in response to an increase in the wage. Consumption ($) G U1 R D Q U0 D F P V E 29 0 70 75 85 110 Hours of Leisure MORE WORK AT A HIGHER WAGE When the substitution effect dominates the income effect, the worker decreases hours of leisure in response to an increase in the wage. Consumption ($) U1 G R D Q U0 F D P V E 30 0 65 70 80 110 Hours of Leisure If income effect is dominant, the person will respond to a wage increase by decreasing his/her labor supply. Should the substitution effect dominate, the person’s labor supply curve will be positively sloped. Wage W* Backward-bending Desired hours of work 31 3. A Graphic Analysis of the Labor-Leisure Choice Two categories of goods: Leisure(L)and Money Income ( M ) Since both leisure and money can be used to generate satisfaction, these two goods are to some extent substitutes for each other. M Indifference Curve: A B C D IC2 A curve connecting the various combinations of money income and leisure that yield equal utility. 32 IC1 L Indifference curves have certain specific characteristics: 1. Any curve that lies to the northeast of another one is preferred to any curve to the southwest because the northeastern curve represents a higher level of utility. 2. Indifference curves do not intersect. 3. Indifference curves are negatively sloped. 4. Indifference curves are convex. When money income is relatively high and leisure hours are relatively few, leisure is more highly valued than when leisure is abundant and income relatively scarce. 33 5. Different people have different sets of IC’s M M L Person who place high value on an extra hour of leisure L Person who place low value on an extra hour of leisure 34 The resources anyone can command are limited. Budget constraint reflects the combinations of leisure and income that are possible for the individual. M The slope of the budget constraint is a graphic representation of the wage rate. E Wage rate = OE/OD 0 D L 35 GRAPHING THE BUDGET CONSTRAINT Consumption ($) wT+V Budget Line V E 0 T Hours of Leisure 36 Note: Full income = wage rate * T →It represents the maximum attainable income. M At point B: MUL/MUM>W or MUL>W*MUM L should increase E B A* IC2 At point C: MUL/MUM<W or MUL<W*MUM L should reduce, or H should increase IC* C IC1 D L IC2:impossible under current condition IC1:possible, but higher level of utility can be attained IC*:utility-maximized level A* :utility-maximization point •An indifference curve that is just tangent to the constraint represents the highest level of utility that the person can obtain given his or her 37 constraint. The Decision Not to Work What happens if there is no point of tangency? M The person’s IC are at every point more steeply than the budget constraint. Pt. D is not a tangency point. There can be no tangency if the IC has no points at which the slope equals the slope of the budget constraint. E D L At this point(D)the person chooses not to be in the labor force. 38 TO WORK OR NOT TO WORK? Are the “terms of trade” sufficiently attractive to “bribe” a worker to enter the labor market? Reservation wage: the lowest wage rate that would make the person indifferent between working and not working. Rule 1: if the market wage is less than the reservation wage, then the person will not work. Rule 2: the reservation wage increases as nonlabor income increases 39 THE RESERVATION WAGE Consumption ($) H Has Slope -whigh Y G X UH E U0 Has Slope -w 0 T Hours of Leisure 40 The Income Effect Nonlabor income: Even if this person worked zero hour per day, he/she will have this nonlabor income. M Note that the new constraint is parallel to the old one. E B A IC2 →The increase in nonlabor income has not changed the person’s wage rate. IC1 D L Pure income effect: The income effect is negative; as income goes up, holding wages constant, hours of work goes down. 41 Income and Substitution Effects with a Wage Increase The wage increase would cause both an income and a substitution effect; the person would be wealthier and face a higher opportunity cost of leisure. N1→N3: income effect → L↑, H↓ N3→N2: substitution effect →L↓, H↑ N1→N2: observed effect Substitution effect dominates. L↓, H↑ Income effect: Had the person received nonlabor income, with no change in the wage, sufficient to reach the new level of utility, he/she would have reduces work hours from N1 to N3. 42 N1→N3: income effect →L↑, H↓ N3→N2: substitution effect →L↓, H↑ N1→N2: observed effect Income effect dominates. L↑, H↓ Note: The differences in the observed effects of a wage increase are due to differences in the shape of the indifference curve. i.e., different preference. 43 • Empirical Findings on the Labor/Leisure Choice (1)The time-series study can be used to look at trends in labor force participation rates and hours of work over time. (2)The cross-section study can be used to analyze the patterns of labor supply across individuals at a given point in time. 44 4. POLICY APPLICATION Virtually all government income maintenance programs-from welfare payments to unemployment compensation-have workincentive effect. (1) Income Replacement Programs Unemployment insurance, worker’s compensation, and disability insurance might be called income replacement programs. →All these programs are intended to compensate workers for earnings lost owing to their inability to work. Note: All these programs in the U.S. typically replace roughly just half of before-tax lost earning. The reason for incomplete earnings replacement has to do with work incentives. 45 Replacing all of lost income could result in overcompensation by generating a higher level of utility than before the loss of income, and would motivate the recipients of benefits to remain out of work as long as possible. M E0 T IC2 When employment ceases, the worker receives benefits equal to E0, he/she will be at pt. T on a higher IC. IC1 46 L (2)Actual Income Loss vs. “Scheduled” Benefits Actual Income Loss: Workers who are either totally or partially disabled receive benefits that replace their actual lost earnings. M D E0 C B A L If the injured worker earned E0 before injury and workers’ compensation replaced all earnings loss up to E0, then workers’ compensated budget constraint would be ABCD line. Note: Throughout the horizontal segment BC, the individual’s net wage is zero. When people cannot increase their income by working, there is usually no incentive to work. 47 Using an impersonal schedule of disability benefits preserves at least some incentive to work because benefits are not reduced if earnings increase. M E D G C → There are greater incentives to work if benefits are scheduled than if benefits are calculated to completely replace earnings losses. B A L Grand benefit according to some schedule without regard to the individual’s actual earnings loss. → Budget constraint BE. Scheduled benefits cause only an income effect. However, if actual earnings loss were to become the benefit, there would be an income effect and substitution effect, and both would work in the same direction. The benefits would simultaneously increase income while 48 reducing the wage rate to zero. 5. CHILD CARE, COMMUTING, AND THE FIXED COSTS OF WORKING (1) Fixed Monetary Costs of Working not work: at point a with utility U1 ab: fixed per-period monetary cost → If the individual works, the budget line starts from point b. 49 a. How large does the wage rate need to be to induce this person to work for pay? →The slope of the budget line bd represent the wage such that any decrease in this wage will cause the individual to drop out of the labor force. This is because utility U1 will no longer be attainable if he/she work any hour. →The wage represented by the slope of bd is this person’s reservation wage-the lowest wage for which he/she will work. 50 b. What would happen to the reservation wages if the fixed costs were to increase to ae? →An increase in the fixed costs of work will tend to raise the reservation wage of potential workers. Consider the change from bg to ef: →Increasing fixed costs of work will tend to increase the hours of work for some workers but cause others to drop out of the labor force. →The net effect on labor supply is ambiguous a priori.51 (2) Fixed Time Costs of Working If the individual does work he/she incurs fixed time costs ab. →The maximum number of hours a day available for work or leisure is T1. At wage represented by bh, he/she would be indifferent between working (pt D) and not working (pt a). 52 reservation wage Suppose that the fixed time costs of work increase from ab to ad, then as long as leisure and income are both assumed to be normal goods, hours of both work and leisure time will be reduced. The increase in fixed time costs of work has an income effect that reduces the worker’s demand for both leisure and the goods income will buy. Given a constant wage rate, a fall in income implies that hours of work have been reduced. Note: The increase in time cost has two important consequences: (a)It reduces full income from og to ok. (b)It reduces total time available for either leisure or work so long as the individual continues to work. 53